- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

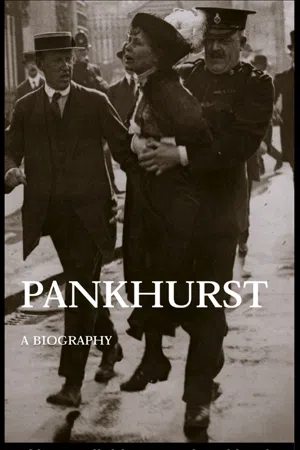

Emmeline Pankhurst was perhaps the most influential woman of the twentieth century. Today her name is synonymous with the 'votes for women' campaign and she is remembered as the most brave and inspirational suffrage leader in history. In this absorbing account of her life both before and after the campaign for women's suffrage, June Purvis documents her early political work, her active role within the suffrage movement and her role as a wife and mother within her family.

This fascinating full-length biography of Emmeline Pankhurst, the first for nearly seventy years, draws upon new approaches to feminist biography to place her within the context of her family and friends. It is based upon an unrivalled range of primary sources, including personal interviews with her surviving family.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Emmeline Pankhurst by June Purvis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

CHILDHOOD AND YOUNG WOMANHOOD (1858–1879)

It is commonly stated that Emmeline Goulden was born on 14 July 1858,1 but her birth certificate records the following day as the date of birth, at Sloan Street, Moss Side, Manchester. Perhaps she was born around midnight and her parents, Robert Goulden, a cashier, and his Manx-born wife, Sophie Jane (née Craine), decided after the birth was registered some four months later, that the 14th was the appropriate date. Perhaps Emmeline herself created the myth many years later; as a young woman she developed a passion for all things French and 14 July was the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille in Paris in 1789, an event that marked the beginning of the French Revolution. Perhaps Emmeline’s birth certificate became lost and she had not seen the recorded date; after all, during the years when she was the leader of the WSPU, she lived like a nomad, without a permanent home, and it would have been difficult to keep family papers under such circumstances. But one thing is certain: Emmeline believed she was born on the auspicious 14th and it is highly likely that her parents told her so. As she said in 1908, ‘I have always thought that the fact that I was born on that day had some kind of influence over my life … it was women who gave the signal to spur on the crowd, and led to the final taking of that monument of tyranny, the Bastille, in Paris.’2

The eldest girl in a family of ten children, Emmeline was a lively and precocious child, the rebellious streak in her nature being enhanced by stories about how her parental grandfather had narrowly escaped death at the Peterloo franchise demonstration in Manchester in 1819 and, with his wife, had taken part in demonstrations in the 1840s against the Corn Laws which imposed duties on imported foodstuffs. Emmeline could read by the incredibly early age of three. The young child also learnt, with a similar ease, how to play the piano at sight but would never practise and it was reading that was her favourite pastime, tales of a romantic and idealistic nature, such as John Bunyan’s The pilgrim’s progress and The holy war, being especially popular.3

The rich, industrial city of Manchester, at the heart of the manufacturing North, was a city of contrasts, with the poor living in overcrowded, insanitary tenements and the more affluent in spacious detached and semi-detached houses. Manchester was also at the forefront of dissenting politics during this period, a time of ‘heart-stirring struggles for constitutional liberty and the freedom of the human mind and personality’.4 Robert Goulden, being on the side of liberation in these matters, was an ardent supporter of the abolitionists in the American Civil War and prominent enough to be appointed to a committee which welcomed to Manchester the anti-slavery campaigner, Henry Ward Beecher, visiting England on a lecture tour. Sophie Goulden was an abolitionist too and frequently explained the evils of slavery to her growing family by reading to them Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s cabin. Almost fifty years later, Emmeline could still vividly recall the thrill of listening, at bedtime, to her mother telling the story of the beautiful Eliza who fled for freedom over the broken ice of the Ohio River. She also recollected how one of her earliest memories was of the time she accompanied her mother to a large bazaar, held to raise money to relieve the poverty of the emancipated black slaves and, entrusted with a lucky bag, she collected pennies from willing supporters of the cause. ‘Young as I was – I could not have been older than five years – I knew perfectly well the meaning of the words slavery and emancipation.’5 Such fundraising events, together with the stories of oppression and liberation, made a permanent impression, Emmeline believed, on her character, awakening in her ‘the two sets of sensations to which all my life I have most readily responded: first, admiration for that spirit of fighting and heroic sacrifice by which alone the soul of civilisation is saved; and next after that, appreciation of the gentler spirit which is moved to mend and repair the ravages of war.’ Such sentiments were further fired by her admiration for Thomas Carlyle’s History of the French Revolution, a book she discovered when about nine years old and which she insisted ‘remained all my life a source of inspiration’.6 As Holton has elaborated, Carlyle’s view of history as an unpredictable process, where individuals were confronted with a choice of ensuring a better world in the future, or of allowing society to degenerate into chaos, a view where revolt could be glorified, not simply justified, was of the greatest importance for understanding Emmeline’s future role in the campaign for women’s enfranchisement and what may be termed her ‘romantic outlook’.7

Robert Goulden prospered in his employment and became a partner and manager of a new cotton printing and bleach works at Seedley, on the outskirts of Salford. His growing family moved to a big white house, Seedley Cottage, surrounded by large gardens and meadows that separated it from the factory nearby. Although Emmeline enjoyed the delights of the countryside, she lived close enough to the poor to gain an insight into the appalling social conditions and hardships under which they laboured. Neither were holidays spent on the Isle of Man, where her parents owned a house in Douglas Bay, entirely carefree for Emmeline. While she joined in the swimming and rowing, country walks and visits to her grandmother and uncle, as the eldest girl in a large family, maturity was forced upon her early as she helped to look after her four younger sisters and five brothers.8 Such a situation was not unusual, even in comfortable middle-class homes where a nursemaid was employed, as Carol Dyhouse has revealed. Looking after younger siblings was considered the most natural duty of the elder middle-class daughters, an early lesson in femininity.9

Despite these early responsibilities, Emmeline remembered her childhood with affection, as a time when she was protected with love and comfort, rather than the deprivations, bitterness and sorrow which brought so many men and women in later life to a realisation of the social injustices of Victorian society. Nevertheless, while still very young she began ‘instinctively to feel that there was something lacking, even in my own home, some false conception of family relations, some incomplete ideal’. This vague feeling took a more definite shape when her parents discussed the issue of her brothers’ education ‘as a matter of real importance’ while the education of Emmeline and her sister Mary, about two and a half years Emmeline’s junior, was ‘scarcely discussed at all’.10 Robert and Sophie Goulden, although more liberal than many other Victorian parents, held traditional views about the expected future role of their daughters, mainly that they should be prepared for lives as ladylike wives and mothers rather than as paid employees.11 Thus despite the fact that Emmeline was a gifted child whom her brothers nicknamed ‘the dictionary’12 for her command of language and accurate spelling, she followed the typical path of most middle-class girls of her day by attending, when she was about nine years old, a small, select, girls’ boarding school, run by a gentlewoman. The main aim of such family-like institutions was not academic but the cultivation of those social skills that would make their pupils attractive to potential suitors.13 Although Emmeline was taught reading, writing, arithmetic, grammar, French, history and geography, undoubtedly in an unsystematic way, the prime purpose was to inculcate in the pupils ‘womanly’ virtues, such as making a home comfortable for men, a situation she found difficult to understand. ‘It used to puzzle me … why I was under such a particular obligation to make home attractive to my brothers. We were on excellent terms of friendship, but it was never suggested to them as a duty that they make home attractive to me. Why not? Nobody seemed to know.’ An answer came to her question one evening when, feigning sleep in her bed, she heard her father say, ‘What a pity she wasn’t born a lad.’ Emmeline’s first impulse was to sit up in bed and protest that she did not want to be a boy but, instead, she lay still, listening to her parents’ footsteps pass towards the next child’s bed. For many days afterwards, she pondered on her father’s remark but decided she did not regret being a girl. ‘However, it was made quite clear’, she recollected, ‘that men considered themselves superior to women, and that women apparently acquiesced in that belief.’14

Such a view Emmeline found difficult to reconcile with the fact that both her parents were advocates of equal suffrage for women and men, another frequent topic of debate in the Goulden household. Her devoted father, to whom his eldest daughter was his favourite child, used to set Emmeline the task of reading the daily newspaper to him, as he breakfasted, an activity that helped to sharpen an interest in politics. Still young when the Reform Act of 1867 was passed, which extended the parliamentary franchise to all male householders and to men paying more than £10 annual rent in the boroughs, she did not understand fully the implications of the changes that were introduced but remembered well some of the controversy that it provoked. A chance to show her support for the Liberal Party, of which her father was a member, came in the first election after the bill when the daring Emmeline persuaded the willing Mary to follow her in the mile-long walk to the nearest polling booth, in a rough factory district. Since both girls were wearing new winter green frocks with red flannel petticoats, the colours of the Liberal Party, she had suddenly decided that they should parade before the queues of waiting voters, daintily lifting the edge of their skirts, in order to encourage the Liberal vote. When the nursery maid caught up with the children, she angrily stopped such a display of impropriety.15 The incident showed, perhaps, an early liking for performance that may have been related to her father’s main hobby. Robert Goulden was a well-known amateur actor in the Manchester area, especially of Shakespeare’s plays, which he knew by heart, and the young Emmeline probably watched him, admiring his skills.16

When she was fourteen years old, the future leader of the WSPU attended her first suffrage meeting. Coming home from school one day she met her mother setting out to hear Lydia Becker who was Secretary of the influential Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage and also a key figure in the Victorian women’s rights movement. An enthusiastic Emmeline begged to be taken too since she had long admired Miss Becker as the editor of the Women’s Suffrage Journal which came to her mother every month. A plain, bespectacled woman with her hair pulled back tightly into a bun at the back of her head, Lydia Becker’s appearance and rather stern countenance was frequently the butt of gibes in a sexist press.17 But she was much in demand as a suffrage speaker. Her talk this day enthralled and excited the schoolgirl so much that she left the meeting ‘a conscious and confirmed’ suffragist. ‘I suppose I had always been an unconscious suffragist. With my temperament and my surroundings I could scarcely have been otherwise.’18 Manchester was then the centre of the women’s enfranchisement campaign and other important activists who lived in the city or surrounding areas included Elizabeth Wolstenholme, Ursula Bright and her husband, Jacob, and Dr. Richard Pankhurst, a radical barrister who was a member of the far left of the Liberal Party and an advocate not just of women’s rights but also other advanced causes of the day.19

Emmeline, who had not yet met Richard Pankhurst, the man destined to become her husband, was preoccupied with her forthcoming stay in France. Her parents wanted their eldest daughter to be an accomplished young lady and so sent her to Paris where she became a pupil at the Ecole Normale de Neuilly, a pioneer institution in Europe for the higher education of girls. The Paris of her schooldays was a city still bearing the scars of the recently ended Franco- German war in which France had been defeated; even Emmeline’s school, which had served as an infirmary for the sick and wounded, had walls riddled with shell and the marks of bullet shots.20 But worse was the suffering of the Parisians under the indemnity that had been imposed upon them. From this time onwards, Emmeline developed a lifelong prejudice against all things German and a lifelong love for all things French, including Paris itself, ‘the city of her desire’.21 The headteacher of her new school, Mademoiselle Marchef- Girard, believing that girls’ education should be as thorough and as practical as that of boys’, included in the curriculum subjects such as chemistry, bookkeeping and the sciences, as well as the ladylike skill of embroidery. But since the lessons were conducted in French, in which Emmeline was not fluent, she was unable to participate fully. The change of circumstances and the climate upset her disposition so the visiting doctor advised she be excused classes and be allowed to run around and amuse herself. Taking full advantage of the freedom granted to her, Emmeline explored Paris with another solitary pupil, the beautiful Noémie Rochefort who had been placed in the school for refuge rather than instruction. The two young women became close friends and roommates, Emmeline listening intently to the anxious Noémie’s constant talk about her father, Henri Rochefort, a well-known Republican, communist and swordsman who had been imprisoned in New Caledonia for the part he had played in the disastrous Paris commune. The stories about his duels, imprisonment and daring escape in an open boat fired the imagination of the impressionable pupil from Manchester who quickly acquired fluency in the French language.

Emmeline spoke highly of the liberal curriculum taught to the pupils, which she supplemented by reading a large number of French novels. The founder of the school and editor of Nouvelle Revue, Madame Adam, took an interest in her English pupil and was ‘exceedingly kind’, inviting Emmeline not only to her house but also to her soirées where many famous men of the day were present.22 Such socialisation into the appropriate form of conduct considered suitable for young middle-class women worked its magic. Emmeline, now eighteen years old, returned home to Manchester:

having learnt to wear her hair and her clothes like a Parisian, a graceful, elegant young lady … with a slender, svelt figure, raven black hair, an olive skin with a slight flush of red in the cheeks, delicately pencilled black eyebrows, beautiful expressive eyes of an usually deep violet blue, above all a magnificent carriage and a voice of remarkable melody. More than ever she was the foremost among her brothers and sisters.23

Despite Emmeline’s sophistication, however, she was still expected to take her place as the eldest daughter in a large family, doing various feminine tasks such as helping to dress her sisters, redecorating the drawing-room, and looking after the youngest girl. In any crisis, she never seemed to be at a loss. When a lamp, which was lit, became detached from the ceiling at a school event, she had the presence of mind to rush forward and catch it in her hands; when some window curtains caught fire in the house, she hastily pulled them down to put out the blaze. Yet, despite such decisiveness and confidence in these respects, Emmeline could be painfully shy of any sort of artistic or emotional expressiveness. She was once overcome by nervousness at a school concert, unable to play a few bars alone on the piano; the embarrassing situation was saved by a quick thinking teacher who leant across the young woman’s shoulders and played the necessary notes.24

As a middle-class daughter at home, involved in her family’s domestic routine, Emmeline missed the variety and excitement of her Paris schooldays and longed to return to the city she had taken to her heart. An opportunity came the following year when Mary, in her turn, was sent to the Ecole Normale de Neuilly and Robert Goulden allowed Emmeline to accompany her. As what was termed a ‘parlour boarder’,25 Emmeline had plenty of free time to renew her friendship with Noémie, now the wife of the Swiss painter, Frederic Dufaux, and the mother of a baby girl. Noémie was keen for her dear friend to marry and live near her in Paris, where they could both be mistresses of their own households and cultured hos...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- WOMEN’S AND GENDER HISTORY

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1: CHILDHOOD AND YOUNG WOMANHOOD (1858–1879)

- 2: MARRIAGE AND ENTRY INTO POLITICAL LIFE (1880–MARCH 1887)

- 3: POLITICAL HOSTESS (JUNE 1887–1892)

- 4: SOCIALIST AND PUBLIC REPRESENTATIVE (1893–1897)

- 5: WIDOWHOOD AND EMPLOYMENT (1898–FEBRUARY 1903)

- 6: FOUNDATION AND EARLY YEARS OF THE WSPU (MARCH 1903–JANUARY 1906)

- 7: TO LONDON (FEBRUARY 1906–JUNE 1907)

- 8: AUTOCRAT OF THE WSPU? (JULY 1907–SEPTEMBER 1908)

- 9: EMMELINE AND CHRISTABEL (OCTOBER 1908–JANUARY 1909)

- 10: ‘A NEW AND MORE HEROIC PLANE’ (JANUARY–SEPTEMBER 1909)1

- 11: PERSONAL SORROW AND FORTITUDE (SEPTEMBER 1909–EARLY JANUARY 1911)

- 12: THE TRUCE RENEWED (JANUARY–NOVEMBER 1911)

- 13: THE WOMEN’S REVOLUTION (NOVEMBER 1911–JUNE 1912)

- 14: BREAK WITH THE PETHICK LAWRENCES (JULY–OCTOBER 1912)

- 15: HONORARY TREASURER OF THE WSPU AND AGITATOR (OCTOBER 1912–APRIL 1913)

- 16: PRISONER OF THE CAT AND MOUSE ACT (APRIL–AUGUST 1913)

- 17: OUSTING OF SYLVIA AND A FRESH START FOR ADELA (AUGUST 1913–JANUARY 1914)

- 18: FUGITIVE (JANUARY–AUGUST 1914)

- 19: WAR WORK AND A SECOND FAMILY (SEPTEMBER 1914–JUNE 1917)

- 20: WAR EMISSARY TO RUSSIA: EMMELINE VERSUS THE BOLSHEVIKS (JUNE–OCTOBER 1917)

- 21: LEADER OF THE WOMEN’S PARTY (NOVEMBER 1917–JUNE 1919)

- 22: LECTURER IN NORTH AMERICA AND DEFENDER OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE (SEPTEMBER 1919–DECEMBER 1925)

- 23: LAST YEARS: CONSERVATIVE PARLIAMENTARY CANDIDATE (1926–JUNE 1928)

- 24: NICHE IN HISTORY

- NOTES

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY