![]()

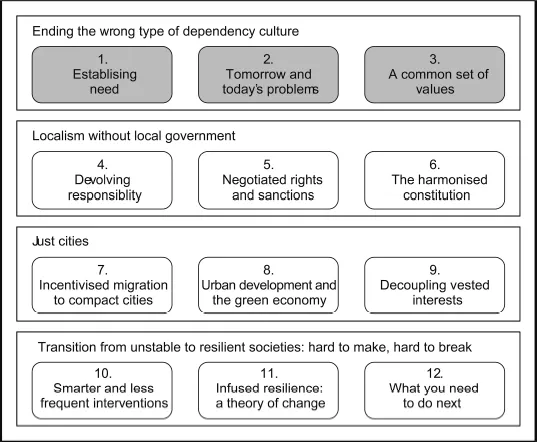

Part One

Ending the wrong type of

dependency culture

![]()

1

ESTABLISHING NEED

Just 19 per cent of parliamentarians are women and we're more than half of humanity … There are 19 female heads of states in 192 member states. And just 15 Fortune 5000 chief executives are women. You see we have a problem. Gender equality will only be reached if we are able to empower women.

Michelle Bachelet, Executive Director, UN-Women (commenting on a gender

study by the World Economic Forum that found greater productivity in

countries where women achieved senior positions) (Martinson, 2011)

Gaps in resiliency work to date?

There is a vast body of relevant literature that provides helpful thinking on resilience in municipal government, sustainable communities or eco-cities and local empowerment or self-organisation. Whilst the language and terminology or points of departure vary, there is a wealth of learning about common lessons to be drawn as well as areas for further development, from which the need for this book emerged as highlighted previously.

Upon critical appraisal of these debates, a number of shared concepts or strengths can be decanted. These are as follows:

- The need to understand the underlying problems of the current economic model, how this causes unsustainable development and what needs to change – including Benello et al. (1997) Building Sustainable Communities: Tools and Concepts for Self-Reliant Economic Change, Khunstler (2005) The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Catastrophes of the 21st Century and Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) The Spirit Level.

- Using ideas or models of resilience as a pathway to more sustainable or prosperous places. These range from an ability to bounce back from shocks through to learning and adapting, as well as the know-how to self-manage – including Mclnroy and Longlands (2010) Productive Local Economies: Creating Resilient Places and Shaw (2010) The Rise of the Resilient Local Authority?.

- An increasing recognition of the need for scenarios on the future of urban settlements given the vital role of cities in natural resource flows and the population's wellbeing – including Brugmann (2009) Welcome to the Urban Revolution: How Cities are Changing the World, Newman et al. (2009) Resilient Cities: Responding to Peak Oil and Climate Change, UN-Habitat (2011) What Does the Green Economy Mean for Sustainable Urban Development? and World Bank (2010b) Eco2 Cities: Ecological Cities as Economic Cities.

Although these can be helpful, they also share some common weaknesses or gaps, because they display either:

- an absence of debate about a set of universal or common values which bring people or stakeholders together for the general good, or the interface between local and national constitutions to enable this;

- a lack of consistency and clarity in the use of terms such as ‘resilience’ and ‘green economy’, or how they link to the concept of ‘sustainability’, which results in narrow or silo interpretations that make the case for universal change difficult to argue;

- a limited analysis of the need for a different type of governance to set standards and monitor implementation, ranging from the poor financial health of so-called ‘greenest cities’ (i.e. predications that some of these cities will ‘go bust’: Moya, 2010) through to the accountability of major urban infrastructure schemes (e.g. rapid transport and energy distribution networks) that involve new and complex forms of public–private partnerships.

Each of these will be discussed in subsequent chapters and will culminate in the theory of change in Chapter 11. To reach a fuller understanding of the relevance and gaps to the debate, some of the key texts are discussed in more detail below.

A review of the literature

Shaw (2010) provides a fascinating short history of the term ‘resilience’ and its changing use in local government. Citing Holling (1973), Shaw explains how the term was initially used in an ecological context and defined as the ‘measure of the persistence of systems and of their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationships between populations or state variables’. The concept was subsequently taken up with regard to civic emergencies such as disruption to utility suppliers or a terrorist attack. More recently, it has developed to focus on how individuals and communities cope with external stresses and disturbances caused by environmental, social or economic change such as climate change or financial recession, notably in North America, Australia and New Zealand. Referring to Adger (2010) Shaw argues that resilience can be viewed as involving three elements: the ability to absorb perturbations and still retain a similar function; the ability of self-organisation and the capacity to learn; and the ability to change and to adapt. Shaw concludes that the maturation of the use of the concept of resilience amongst local authorities should be welcomed, but cautions that further research is needed to ensure consistency in its understanding and its application. Despite these strengths, Shaw does not go on to discuss the underlying system's failure which causes these problems and which needs to be addressed.

Mclnroy and Longlands (2010) adopt a different approach to Shaw. Here an emphasis on resilience is very much on local economic productivity and sense of place. Coined by them as the ‘boing factor’ (in terms of an ability to bounce back from adversity), resilience ‘differs from sustainability in that it focuses on the proactive capabilities of a system to not simply exist but instead survive and flourish’ (ibid.: 13). Interestingly, Mclnroy and Longlands cleverly put forward a model with measures to assist practitioners, which is very helpful although somewhat limited given that only one of the eight measures relates to the environment and that it focuses solely on climate change, therefore discounting the high cost of the wider mishandling of natural resources such as watercourses or agricultural land. Also, similar to Shaw, the authors do not discuss in any depth the flawed wider systems that lead to an absence of resilience, beyond a reference to local government mismanagement.

In contrast, Benello et al. (1997), Wilkinson and Pickett (2009), Kunstler (2005) and Newman et al. (2009) do attempt to conceptualise the cause of failure, but with quite different conclusions. For Benello et al. the absence of ‘bottom up’ economic leadership is the critical failure of unsustainable communities, whereas for Kunstler, and also for Newman et al., the fossil fuel dependency of cities and the world in general is the root cause of the problem.

Benello et al. (1997) – a seminal book based on the Schumacher Society Seminars of 1982 on community economic transformation – intend to provide essential concepts and institutions for building sustainable communities. They argue that the two basic causes of economic breakdown from ‘top down’ transformation (concentrated wealth, alienation between workers/consumers/residents, lack of self-management from big government, lack of finance for small or local businesses, trade wars and unemployment and welfare payments) are the rules used for owning land and corporations and the government-created monopoly money systems supported by central banking. Consequently, three major solutions identified to avoid this high cost of failure are: (i) community land trusts and other forms of community ownership of natural resources (e.g. housing, forests), (ii) worker-managed enterprises, and (iii) community currency or banking. In support of their argument Benello et al. cite the impressive example of the Woodland Community Land Trust in Tennessee, USA (a vehicle for residents to regain control of lands exploited by corporate owners and then abandoned). In addition they highlight the Seikatsu Club in Tokyo, Japan, a consumer cooperative with an emphasis on ecological sustainability and consumer control of the marketplace (e.g. food, clothes etc).

In putting forward these high-level concepts and tools for self-reliant economic change, perhaps it would be helpful for Benello et al. to produce a supporting narrative, in terms of the common purpose or values that citizens or communities would sign up to in order to deliver against this. The authors’ conclusions are clearly influenced by Schumacher's ‘small is beautiful’ doctrine and so may also be limited by their relevance to today's urban reality as they do not offer ways to ‘scale-up’ to city-level interventions. This is particularly relevant when considering that half the world's population lives in cities (Brugmann, 2009). Neither did the authors extend conclusions to major urban infrastructure upon which locally owned natural assets may be dependent (e.g. water or energy distribution networks) and which in isolation or combination undermine the authors’ core proposition of ‘self-reliance’.

Wilkinson and Pickett's (2009) groundbreaking analysis of the impact of how inequalities hamper our shared prosperity correlates with much of Benello et al.’s thinking on the causes of unsustainable communities. Citing the links between income inequality and the financial crashes of 1929 and 2008, they argue that greater equality is in everyone's interest as it reduces the need for big government. For example, there are more police, prisons, health and social services in the USA and UK in comparison to Japan and Norway – and so they are more expensive to maintain. (The cost–benefits of avoiding these failures are explored in more detail in Chapter 2).

Newman et al. (2009), by comparison, recognise the vital role cities play in human resilience, but examine it through a response to peak oil and climate change. Kunstler (2005) also focuses on the emergency of fossil dependency, although with only a passing reference to the city. Newman et al. argue that resilience is destroyed by fear and built upon hope. Citing the examples of New York after 9/11 and London after the 7/7 bombings, the authors argue that fear stopped people from congregating on the streets or using the underground but that both steeled themselves to carry on, for instance in the case of the latter with billboard signs declaring ‘7 million Londoners, 1 London’ organised by the city government in the immediate aftermath. Extending the reasoning, Newman et al. went on to conclude that finding hope in the steps that must be taken to create resilient cites in the face of peak oil and climate change is important. The context to this is that cities have grown rapidly in an era of cheap oil since the 1960s and 1970s and now together consume 75 per cent of the world's energy and emit 80 per cent of the world's greenhouse gas emissions; at a time when ‘peak oil’ – the maximum rate of production of oil, recognising that this is a finite natural resource, subject to depletion (Newman et al., 2009) – will be reached. In the UK and USA the estimated date to reach peak oil is somewhere between now and 2020. And that some cities are less well adapted and vulnerable to change, for instance, Atlanta, USA needs 782 gallons of gasoline per person each year for its urban system to work, but in Barcelona it is just 64 gallons (Newman et al., 2009). Looking at scenarios for the future of cities, Newman et al. call for the resilient city to be shaped by a ‘sixth wave’ of industrialism – the beginning of an era of renewable and distributed technologies for heat, power and transit which are facilitated by higher-density, ‘walkable’, mixed-use developments that are integrated through a ‘smart grid’. This would be good news for everyone in terms of economic security, better health and an improved environment. (Scenarios for the future of cities are something we return to in Chapter 2.)

Similarly, Kunstler (2005) argues that our dependency on fossil fuel is one of a number of converging catastrophes of the twenty-first century in addition to peak oil and over population. Although, in contrast to Newman et al.’s hopeful message, Kunstler argues that we are sleepwalking to the future. Kunstler's assertion is that:

One conclusion he draws from this is that ‘nuclear power may be all that stands between what we identify as civilisation and its alternatives’ (ibid: 146) on the basis that other renewable options are not currently viable.

A downside to both Newman et al. and Kunstler is an absence of debate about the governance of these major new urban infrastructures, be they smart grids or other technologies. (This is an issue which is analysed in more depth in Chapter 7.)

Similar to Newman et al., Brugmann (2009) places the role of city planning at the centre of human progress. However, his point of departure is social and economic development to address these problems as opposed to Newman et al.’s primary focus on environmental sustainability. ‘Cities are changing everything … for better or worse’ states Brugmann (2009: ix), noting that half the world's population now live in cities, equivalent to 3.5 billion people, and will be joined by a further 2 billion people over the next 25 years. He argues that success in a world increasingly organised around cities requires a new practice of design, governance and management called ‘urban strategy’. Citing the examples of Barcelona (Spain), Chicago (USA) and Curitiba (Brazil), Brugmann concludes that ‘strategic cities’ like these need to master the 3 faculties of: (i) a stable governing alliance with the power and resources to align interests in the pursuit of a common goal; (ii) an explicit and detailed body of practices to translate this vision into practical forms of building and design; and (iii) a set of dedicated institutions with the technical talent to implement these solutions.

Whilst a formidable narrative, the comparative weaknesses of Brugmann are: (i) the lack of detail around what a common set of values may be to shape any common advantage; (ii) only a passing reference to the environmental limits of this economic and social development; and (iii) the absence of any debate about the questionable financial standing of these ‘strategic cities’, which suggests a disconnect with the failures of the underlying economic model (noting again that some commentators say 100 US cities face financial ruin: Moya, 2010). Again, these are topics we will return to in subsequent chapters of the book.

The World Bank (2010a, 2010b) and UN-Habitat (2011) both take the importance of cities a step further (albeit in quite distinct ways), arguing that we need to better understand the interface between city planning and material or resource flows; that is, to ensure there is an integrated approach that allows for better resource efficiency, life-cycle analysis in investment decision-making and greater social equity. One key difference between the two reports is that UN-Habitat strongly emphasise the interface between sustainable urban development and the ‘green economy’, and in particular the need to more clearly define the term (e.g. is it about uncoupling carbon from growth or prosperity?) as well as the good governance of major new urban infrastructure under this banner involving public–private partnerships (PPPs) which will shape the future of entire cities for generations. Which, interestingly, is a theme that is absent from important work on the green economy by the lead agency UNEP (2011b) thus far. The green economy is a concept we will return to in Chapter 7.

As well as this literature, other sources of critical insight, such as applied research amongst trade associations and practitioner networks such as APSE or ICLEI–Local Governments for Sustainability, is also recommended. More details are contained in Appendix 2.

Conclusions

- There is a wealth of learning in resiliency theory and practice. In particular there is an impressive body of work on the underlying problems with the current economic system, with an increasing recognition of the importance of urban planning in creating less fragile societies.

- Gaps still remain, however. Notable deficiencies includ...