![]()

1

The veil of Antipodean pre-history

In the late decades of the nineteenth century European scientists arrived at a startling conclusion. They realized that not only had the earth existed for a vast length of time, but also humans had lived in that ancient world. The realization that people had existed in a period so remote it was long before the invention of writing brought with it the puzzle of how modern researchers could learn of those ancient lives. Nineteenth century archaeologists sometimes wrote poetically about their concern that we may never have detailed knowledge about the ancient human past before written records. For example, the Scandinavian scientist Sven Nilsson (1868), one of the founders of archaeology, described the lives of ancient people, prior to the advent of written records, as being enveloped in obscurity, while Victorian politician and scientist Sir John Lubbock (1872) employed a similar metaphor, saying the past is hidden from the present by a veil so thick that it cannot be penetrated by either history or tradition. Nowadays the task of seeing beyond this veil of obscurity, to reveal something of the unwritten past, falls mainly on archaeology, a distinctive scientific discipline. By studying the material remains of past human activities archaeologists make statements about the lives of people long dead, and reconstruct an image of their economy, social interactions and perceptions of the world.

Archaeologists now think that Australia was inhabited more than 50,000 years ago by humans who were ancestors of modern Australian Aboriginal people; but we have written records of their lives for only the final centuries of that long occupation. European sailors left written impressions of coastal dwelling Aborigines from the seventeenth century onwards, British settlers wrote of Aboriginal people and their land at the end of the eighteenth century, while in isolated parts of the continent European explorers did not glimpse Aboriginal people until late in the nineteenth century. Their documents form the foundations of many interpretations of Australian Aboriginal life during the historic period. Of the humans who lived in Australia thousands of years earlier, those historical records tell us little or nothing. For knowledge of the long passage of human occupation prior to written records, called the pre-historic period because it precedes the first written or historical documents, we must turn to other kinds of records. Archaeological investigations of the buildings, artefacts, food debris, quarries, art works and skeletons of ancient Aboriginal people who lived in Australia during pre-historic times form the primary source of information with which we can tell the story of those people. Additional studies of genetics, reconstructions of past environments, physical and chemical information about the ages of objects, supplement archaeological information and help answer questions about the human occupation of ancient Australia.

The quest to see through the ‘veil’ that separates us from a view of the human past in Australia must begin with an explanation of why archaeologists find it difficult to interpret ancient materials. One process creating ambiguity is the preservation of only some residues of cultural activities and the subsequent destruction and disturbance of archaeological objects, making it hard for archaeologists to develop detailed anthropological-like reconstructions of ancient events. Another way in which the past is obscured is when the methods used to study it actually prevent ancient activities from being recognized. For example, researchers often used written descriptions of Aboriginal ways of life in the historical period to create detailed stories about the pre-historic past, a practice which imposed images of recent cultures on the lives of ancient people, thereby overlaying the past with reproductions of recent life ways. To the surprise of many people first studying archaeology, the principal complication confronting archaeologists is how our knowledge of the modern, historical world can and should be used to reconstruct stories about the ancient, pre-historic world!

How and why archaeologists used historic records

In precisely the same period that European exploration and settlement of Australia began, the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, archaeological thinking was emerging in the scientific traditions of Western Europe. At that time people became interested in incorporating ruins and relics into their understanding of the past. Initially it was thought that the age of the world was recorded in biblical genealogies, that it was only about 6,000 years old, and that much of human history was accurately recorded in historical documents such as the Bible (Grayson 1983; Trigger 1990). With those attitudes early archaeologists thought all archaeological ruins were the work of historically known tribes, and their investigations focused on questions of which tribe was responsible for each ruin. This interpretation reflected widely held views that scriptures, classical poems and early histories contained all that could be known about the past, and that ancient monuments or remains alone taught us little of the past. Such an understanding was based on the idea that archaeological and written records documented the same events, and that humans had not existed before the invention of writing.

Gradually, as archaeologists such as Lubbock and Nilsson demonstrated that many of the archaeological objects in Europe were truly pre-historic, it became necessary to find ways of thinking about archaeological discoveries without using the historic records from Europe. In the second half of the nineteenth century European archaeologists such as John Lubbock frequently used observations of indigenous peoples around the world as a source of inspiration in creating their stories of the European past. In Britain this approach, now termed ‘cultural evolutionism’, was derived from enlightenment ideas that humans had gradually progressed as past generations had used their reasoning capacities to improve their lives. It was commonly believed that organisms, including humans, had an ‘internal drive’ propelling them to higher levels of complexity. For archaeologists and historians this encouraged the idea that human cultures around the world inevitably developed in the same direction, progressing through a number of stages until modern civilizations appeared. Sven Nilsson, for example, believed that all civilizations started as hunters and gatherers, became nomadic herds-folk before becoming sedentary farmers, which enabled them to develop a political state with military and bureaucratic organizations. In the nineteenth century this proposition helped to make sense of the archaeological sequence then being discovered in Europe. Researchers such as Edward Tylor (1871) and Lewis Morgan (1877) suggested that if different cultures around the world progressed from one stage to another at different times observations of less ‘advanced’ societies in remote places could supply details about pre-historic life in Europe.

This intellectual journey of nineteenth century European archaeologists, with their story that all humans developed along the same pathway, had important consequences for how scientists explored the pre-history of Aboriginal people in Australia. Although the idea that all societies must develop in the same way has now been shown to be untrue, these consequences shaped perceptions of Aborigines and their past among early archaeologists, and continue to subtly influence the theory and practice of Australian archaeology.

One consequence of cultural evolutionary views was the establishment of a tradition of archaeological interpretation that relied on the use of information about recent indigenous people. Use of written, historical records about recent societies to provide details about the lives of pre-historic peoples represents an ‘analogy’. Using this analogical argument involved identifying features in a historical society which archaeological debris shows also existed in an ancient society, then inferring both societies shared further similarities not demonstrated by archaeological evidence (Salmon 1982). Although analogies can be potentially helpful to archaeologists they can also be dangerous, because they can produce narratives of pre-historic life that merely borrow from stories of recent life, implying that little has altered over time. Archaeologists therefore need to be careful that their use of analogies from history does not hide change in the nature of human life during pre-history.

Because pre-historic humans lived differently from the way present-day scientists live, it is important to recognize that some stories created about the past reflect modern perspectives on the world rather than the behaviour and attitudes possessed by ancient people. For this reason archaeologists have used historical accounts of non-European societies to give them insights into other cultures, and assist them to imagine societies unlike their own. With a greater understanding of subsistence strategies, technology, and social systems foreign to their own socio-economic lives, archaeologists believed they could interpret the archaeological record without imposing inappropriate European images on ancient peoples. Using this argument, generations of Australian archaeologists sought to avoid ‘Eurocentric’ interpretations of evidence for the ancient Aboriginal past by immersing themselves in historical descriptions of Aboriginal life. Of course this approach never really avoided European visions: depictions of historical Aboriginal people were still interpretations by Europeans of what they saw. Furthermore, as cultural outsiders, early European explorers and settlers altered the way Aboriginal people behaved and often recorded situations that they themselves were responsible for creating. Even worse, it would be curious if archaeologists had such limited imaginations that they relied on historical descriptions of recent societies, such as the ethnographies compiled by anthropologists, as their sole source of inspiration. Societies which existed in the historic period probably represented only a fraction of the cultural diversity that existed throughout pre-history; recent societies do not necessarily resemble all societies which existed in the distant past (Wobst 1978; Bailey 1983; Murray 1988). Nevertheless, the idea that understanding of Aboriginal life in historic times helps archaeologists reconstruct Aboriginal life in ancient times has been very popular in Australia.

A second consequence of the cultural evolutionist idea that all human societies passed through the same stages of development was the belief that Australian Aborigines had progressed only a small distance along the evolutionary path, and had therefore changed little during their occupation of Australia. Adam Kuper (1988) pointed out that images of naked, black, hunters and gatherers, combined with the recentness of European discovery of the continent and the notion that Australia had been isolated, led to the thought that nineteenth century Australian Aborigines represented the kind of early society that had died out elsewhere. This perception promoted notions of Aborigines as a simple, unchanging society. Late nineteenth century anthropologists were convinced that Australia reflected ‘primitive’ society, and important observers of Aboriginal society were influenced by the interpretation of Aborigines as the epitome of the unchanged primitive. This shaped the nature of the diverse nineteenth century observations of Aborigines; from the focus on religion (Kuper 1988) to the search for rigid concepts about stone tools (Wright 1977) many of the early records of Aboriginal life reflected these attitudes. Since historical observers expected that Aborigines had lived since the earliest periods without substantial change it was easy to think that descriptions of Aboriginal life and society during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries could give archaeologists an insight into how Aborigines lived in more ancient times.

Australian archaeology was therefore considered privileged to have a large number of historical records of eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth century Aboriginal life; many researchers made use of those records to imagine how the past might have been. Australia is also frequently cited as an outstanding example of long-term continuity of economy, ideology and social life; an idea that promoted rhetoric of Aboriginal society as the longest continuous culture in existence. These propositions are not separate but are actually two parts of a single idea, each sustaining the other: if the culture has not changed, historical Aboriginal practices tell us of the operation of pre-historic society, while using historical records helped create an image of the past that looks like the present and invites us to think there has been little or no change. How pervasive and hazardous is this tradition of incorporating historical images of Aboriginal people into archaeological reconstructions of ancient human life in Australia? Let us take, as an example, stories offered by archaeologists about one well-known archaeological site.

Lake Mungo and the historic image

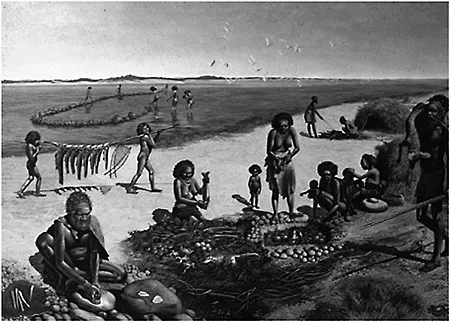

The acclaimed World Heritage site of Lake Mungo, a dry inland lake in the southeast of Australia, is one of the oldest archaeological sites in the continent. Discovered early in the archaeological exploration of Australia, the interpretations of this site influenced not only generations of archaeological thinking but also the public understanding of Australia’s human past. Food debris, artefacts, fireplaces and human skeletons preserved in the sands and clays at the side of the lake are some of the most significant and well-studied archaeological materials in the continent. Surprisingly, many interpretations offered by archaeologists were more strongly influenced by images of historical Aboriginal life than by the archaeological material. Ethnographic images can be seen in Figure 1.1, Giovanni Caselli’s remarkable reconstruction of life at Lake Mungo published by Bernard Wood (1977) as an aide to depicting daily life there more than 30,000 years ago. As Stephanie Moser (1992) has pointed out, this figure reveals the pervasive influence of ethnography on thinking about the past. While some objects and activities in the painting are similar to those that are known to have occurred at ancient Lake Mungo, others do not reflect the archaeological record. For example, the species of animals being captured and cooked by people in the painting are the same as those species whose bones were found in the archaeological deposits. However, some stone artefacts shown in the painting, such as the stone axe being ground by the man in the lower left, are not known in the excavations of Lake Mungo. When the lake existed, axes were used only in distant regions, thousands of kilometres away; they were recovered from sites near by Lake Mungo but only tens of thousands of years after the time represented in the painted scene. Evidence for many things shown in the painting, such as the nature of clothing, existence of jewellery, kinds of fishing gear, construction of huts, sexual division of labour and ‘initiation’ scars on the bodies of men, have never been found in the archaeological deposits at Lake Mungo. All those details in the painting reflect a generalized, even stereotyped, scene of Aboriginal life as presented in historical ethnographies of Australian deserts rather than a reconstruction of the past from the archaeological evidence. The image of ethnographic life contained within the picture has merely been given the veneer of antiquity by the addition of archaeological objects acting as props.

This subtle yet powerful use of ethnographic information, not to assist archaeological interpretations but to supplant them, is not confined to pictorial representations of ancient Lake Mungo; it is also found in many texts written by archaeologists. The idea revealed in Caselli’s painting, that Aboriginal life in the past was much the same as it was in the historic period, reflects interpretations of archaeological evidence from Lake Mungo. For example, as a youthful field archaeologist Harry Allen (1974) interpreted the sparse archaeological evidence in the light of his knowledge of the seed collecting and consumption of Bagundji Aboriginal group,

who lived in the area during the historic period. He concluded that in the nineteenth century Bagundji relied on cereals as a seasonal food, their cereal processing used grindstones, and that grinding stones found in archaeological sites more than 15,000 years old had similarly been used to process cereals. He therefore argued that seed consumption was part of the subsistence pattern for much or all of the last 15,000 years. By filling ‘gaps’ in his archaeological evidence with details obtained from historical observations of Bagundji life, Allen created a vision of the ancient past at Lake Mungo which implied very little change during long periods of time. Allen and others have now shown that this and many other interpretations of unchanging behaviour were wrong. Archaeological evidence at Lake Mungo documents a series of economic and social changes, but many archaeologis...