- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Evangelical Protestantism in Ulster Society 1740-1890

About this book

This major new book represents the first serious study of Irish evangelicalism. The authors examine the social history of popular protestantism in Ulster from the Evangelical Revival in the mid-eighteenth century to the conflicts generated by proposals for Irish Home Rule at the end of the nineteenth century. Many of the central themes of the book are at the forefront of recent work on popular religion including the relationship between religion and national identity, the role of women in popular religion, the causes and consequences of religious revivalism, and the impact of social change on religious experience. The authors draw on a wide range of primary sources from the early eighteenth to the late nineteenth century. In addition, they display an impressive mastery of the wider literature on popular religion in the period.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Evangelical Protestantism in Ulster Society 1740-1890 by David Hampton,Myrtle Hull in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

From international origins to an Irish crisis 1740–1800

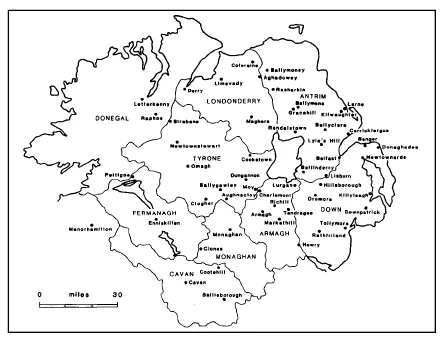

Map 1 Places mentioned in the text

[1]

The rise of evangelical religion 1740–80

And I will multiply upon you man and beast; and they shall increase and bring fruit: and I will settle you after your old estates, and will do better unto you than at your beginnings: and ye shall know that I am the Lord. (Ezekiel 36:11)

And I will gather the remnant of my flock out of all countries whither I have driven them, and will bring them again to their folds; and they shall be fruitful and increase. (Jeremiah 23:3)

Writing in the middle of the nineteenth century the prolific clerical essayist Abraham Hume suggested—ironically, in the light of modern views—that when ‘a Prime Minister states, that of all the parts of the United Kingdom, Ireland is his “greatest difficulty”, the Province of Ulster is an understood exception’. Most of his contemporaries would have endorsed both his opinion and his explanation.

It is there that the people of Anglo-Saxon ancestry are found in greatest numbers, and that the modes of thoughts and habits of action bear the closest resemblance to those which are found in Great Britain. There is the stronghold of the United Church of England and Ireland; and there also are found the numerous Presbyterian communities which claim proximate or remote relationship to the Established Church of Scotland. In Ulster, too, partly as a consequence, and partly as a collateral fact, law and order are respected, life and property are secure. The wheels of commerce and social life move smoothly on; allowing for slight exceptional cases, property and population maintain a steady increase; and the vigour of enlarged views finds that, as in Scotland, a soil which was naturally unproductive has nourished a population of high promise. In short, except geographically, Ulster is not Irish at all.1

The links between Protestantism, the British connection, economic prosperity, social stability and enlightened thought were frequently asserted throughout the modem period and, although a vast oversimplification, such assumptions underpinned the cultural and religious attitudes of most Ulster Protestants. Revealingly, perhaps, the above quotation is to be found in Hume’s introduction to a study of the settlement patterns of English and Scottish immigrants, for it is on the canvas of the original settlement patterns that the various shapes and shades of Ulster religion are primarily to belocated. The transfer of land from the native Irish population to successive waves of English and Scottish immigrants began on a relatively small scale with the Tudor monarchy, but at the end of the sixteenth century some 90 per cent of Irish land was still in the possession of Roman Catholics.2The first decade of the seventeenth century brought an acceleration of land confiscation, with the counties of Antrim and Down, and to a lesser extent Monaghan, falling into the hands of private adventurers from Britain. In addition, the Flight of the Earls in 1607 facilitated the more systematic plantation of Armagh, Cavan, Coleraine (later Londonderry), Donegal, Fermanagh and Tyrone. It was the violent upheavals of the Cromwellian and Williamite periods, however, which most decisively altered the balance of political power in the hands of Protestant landlords.3 Their position was further consolidated in subsequent years by the limited but effective imposition of penal laws against Roman Catholics so that by the mid-eighteenth century only a small fraction of Irish land was owned by them. It would be difficult to exaggerate the long-term impact of confiscation and immigration on the social and religious geography of Ulster in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The settlers in Ulster came chiefly from the lowlands of Scotland where the displacement of small Presbyterian farmers and a long tradition of social and economic links with Ulster both encouraged migration and eased its stresses. Those Scottish farmers seeking a better way of life in Ulster were mainly concentrated in the rural areas of the northeast, especially in the counties of Antrim and Down, but they spread also into Donegal and Tyrone. The areas favoured by the English settlers—parts of Counties Armagh, Fermanagh, Cavan and Monaghan, and the eastern shores of Lough Neagh—were easily distinguishable by travellers from Britain long after the first settlements took place. The large farms, neat hedgerows and orchards, and general ‘air of comfort and tidiness’ offered a welcome sign of civilization and effective land utilization to English civil and ecclesiastical dignitaries who found themselves posted to Ireland.4 The native Irish, in contrast, managed to survive in the south and west of Ulster, but in the northeast they were pushed out to the more infertile and inhospitable regions—the mountains, boglands and glens—and were for the most part reduced to the status of under-tenants and labourers.5 It was no accident, therefore, that in eighteenth-century Ireland contemporaries distinguished men chiefly by their ethnicity, wealth and religion, which were held to be, and generally were, closely related to one another. By the mid-eighteenth century, then, Ulster’s religious geography was primarily established by settlement patterns and by three ethnically distinctive denominations—Roman Catholic, Church of Ireland and Presbyterian—which, generally speaking, ministered to pre-assigned communities and only occasionally attempted any kind of proselytism. The fact that the Roman Catholic Church enjoyed the adherence of the vast majority of the Irish population (even in so-called Protestant Ulster Catholics outnumbered Protestants in five of the nine counties), that the Church of Ireland was the established church of a small minority, and that Ulster Presbyterianism was virtually a state within a state, ensured that the province’s religious life would have more than its fair share of ecclesiastical and political turbulence.

It is important at the outset, therefore, to make quite clear that the evangelical Protestantism which affected Ulster religion from the mid-eighteenth century did not create the characteristic divisions of the province, it merely made them more vibrant and more complicated. Secondly, although the ‘Great Awakening’ brought important new features to Ulster’s religious landscape, hotter forms of Protestantism predated this international movement of the mid-eighteenth century. Not only were there small cells of gathered churches including Baptists, Quakers and Congregationalists stemming from the Cromwellian period,6 but there was an indigenous tradition of piety and revivalism within the Scots-Irish Presbyterianism of the seventeenth century. Firmly at the centre of this piety was a ritualized experience of community purification and conversion reaching back to the Sixmilewater revival in Ulster in 1625. Often initiated by populist itinerant preachers and sustained by a zealous laity, revivals in Ulster and the west of Scotland established a tradition which then served as a source of legitimization for fresh outbreaks of religious enthusiasm. Prolonged communion services lasting several days served the same function in Scots-Irish Presbyterian revivalism as love-feasts did in later Methodist revivals. The revivalist tradition in Scots-Irish Presbyterian piety survived into the eighteenth century despite, and partly because of, the growth of a more progressive and rationalist theology and the accompanying disputes over subscription to the Westminster Confession. Conflicts between ministers respectively devoted to moral philosophy and saving faith and between educated ministers and a more simple laity temporarily sapped the revivalistic energies of Scots-Irish Presbyterians, but the tradition was never buried. Indeed the same elements of itinerancy, conversionist preaching and community zeal for holiness and purity emerged again among the Scots-Irish emigrants to the American middle colonies in the 1730s. George Whitefield’s role in the American Great Awakening was therefore not to initiate, but to reinforce, a pre-existing revivalistic strain in Scots-Irish culture. He was thus a catalyst of religious revival, not its instigator.7

The various migrations of the lowland Scots, first to Ulster and then to North America, is but one example of the international dimensions of the mid-eighteenth-century evangelical revival which until quite recently had been studied within absurdly narrow national boundaries.8 Professor Ward has convincingly shown that the roots of eighteenth-centry pan-revivalism can be traced to the displaced and persecuted minorities of Habsburg-dominated Central Europe, in Silesia, Moravia and Bohemia.9 This revival was partly a reaction against the confessional absolutism of much of early eighteenth-century Europe, and was also an attempt to express religious enthusiasm outside the stranglehold of politically manipulated established churches. The social background of these displaced minorities was low and their idea of religion fitted well into the dominant motif of the German Enlightenment, that is, religion ‘as the means and way to a better life’. Revivalistic religion and pietism—the former was simply more urgent than the latter—survived on a diet of bible study, Reformation classics and a cell structure pastored by itinerant preachers. In terms of the international diffusion of evangelical pietism, the most influential group was the Moravians, who not only exercised a decisive influence over the religious development of John Wesley, but made an important and almost unrecorded contribution to the gro wth of evangelical religion in Ireland. The origins of the Renewed Unity of the Brethren— Moravianism—are extraordinarily complicated. Both at the time and ever since it has been variously interpreted as a rebirth of the old pre-Reformation Unity of the Brethren, as a new and potentially destabilizing sect with no right of toleration in the Holy Roman Empire and as an interconfessional religious movement seeking salvation outside the straitjacket of confessional orthodoxy.10 It was in fact a unique product of religious revival with an emphasis on religious empiricism, international mission, the community of believers and an eclectic openness to the spirituality of other religious traditions. The most ‘characteristic expression of their belief, according to Ward, ‘was not the confession of faith, in the Reformation tradition, but the accumulation of archives, the evidence of the way God operated in history. Their leaders, though they were usually theologically aware, were not professional theologians defending a line, but pastors and evangelists writing letters and journals, preaching daily.’11 One such was John Cennick, a Wiltshire itinerant preacher of Bohemian descent and early Methodist associations, who arrived in Ireland in 1746 and quickly built up a large religious society in an old Baptist meeting house in Dublin’s Skinner’s Alley.12 Cennick had come to Ireland with the good wishes of Count Zinzendorf, the Moravian patron of Herrnhut, whom Cennick had met on a visit to the Moravian synod in Zeist in the Netherlands. Cennick’s journal for the next few years is a mine of information about the state of popular Protestantism in Ireland before Wesley’s first visit.13 By the mid-1740s Dublin already had an informal network of religious societies, some established church, some Presbyterian, some Bradilonian and some Baptist. They formed a colourful, argumentative, eclectic and messy religious subculture, full of disputes about the nature of grace, the efficacy of the sacraments and the ownership of buildings. Allowing for the risk of reproducing Cennick’s own evangelical hyperbole it seems that he quickly achieved a pre-eminent position among Dublin’s popular Protestants owing to his preaching ability and his connections with the English and continental Moravian communities. Cennick’s journal conveys a sense of the excitement of those early days.

In this time all things went on with blessed effects in Skinners-Alley where I preach’d twice daily, and the Crowds were so great that those who would hear must be 2 or 3 hours before the time else they could not get in, and tho’ all the windows were taken down that people might hear in the Burrying-Ground Yards etc, yet multitudinous were oblig’d to be disappointed. On Sundays all the Tops of Houses near us, all walls and windows were cover’d with people, and I must get in at a window and creep over their heads to the pulpit if I would preach. Often 7 or 8 Priests have been together to hear me, as well as many of the Church-Clergy and Teachers of all religions and constantly many of them Collegians. Some curious people have several times counted the Congregation and found it generally more than a thousand and once 1323.14

Apart from itinerant preaching and the formation of religious societies, two other early characteristics of popular Protestantism in Ireland soon became evident. First, since voluntary religious societies had no standing before the law,15 they were repeatedly the victims of mobs which Cennick firmly believed were composed of Roman Catholics. A second feature was that early society and band lists showed an unmistakable preponderance of women. A trawl of Cennick’s Moravian society in 1747 showed that out of 526 members, 350 were female, half of whom were either unmarried or widowed. A denominational survey of band leaders showed that 13 were of the established church, 8 were Presbyterian, 6 were Baptist and 5 more comprised a Muggletonian, a Quaker, a Bradilonian, a separatist and a Roman Catholic.16 Early evangelicalism had a knack of gathering up the flotsam and the jetsam of Ireland’s Protestant past.

Perhaps it was inevitable, therefore, that Cennick as a popular evangelical preacher should come to the heartland of Irish Protestantism in Ulster. He was invited by a Ballymena grocer who had been impressed by Cennick’s firm stand against Roman Catholicism, but Cennick’s Arminianism was not well received by Ulster Presbyterians. His second visit in 1748 was more successful both in terms of the crowds he drew and in the pioneer planting of religious societies. By the early 1750s some 30 to 40 Moravian preachers were itinerating in Ulster, servicing 10 chapels and over 200 societies.17R.H.Hutton’s comment that ‘around Lough Neagh the Brethren lay like locusts’ was no doubt exaggerated, but it was nevertheless surprising that Cennick’s labours were so productive in such a short time.18 His success shows that in areas largely settled by puritans, the traditions of a strict and self-denying religious culture had by no means died out. The voluminous surviving records of early Moravian societies reveal the importance of the Reformation emphasis on the priesthood of all believers and a distrust of Irish Catholicism based on a curious mixture of enlightenment hostility to superstition and priestcraft and more conventional bigotry. Unfortunately for the long-term future of Moravianism in Ulster, ‘Swaddler Jack’, as Cennick had become known was not as successful in organizing Moravian societies as he had been in encouraging their formation, and by the time of his death in 1755 the apex of Moravian expansion in Ulster had already passed. The one substantial survival of early Moravian enthusiasm in Ulster was the Gracehill community which was built after the Herrnhut model with Dutch and German help. The aim was to establish a self-regulating Christian village with a chapel, a school, an inn for travellers, and accommodation and workshops for single men and women. Thus, the Moravian approach to evangelism envisaged the creation of numerous quasi-monastic settlements which would be not only inward-looking in the sense that the inhabitants would seek to live a disciplined and charitable Christian life, but also outward-looking to work for the conversion of the whole world. In fact Gracehill never fulfilled its most optimistic aspirations. Its population never exceeded 400, reached its peak between 1790 and 1845 and thereafter became a more mixed religious community.19 Cennick’s importance should not be overlooked, however, as a link between seventeenth-century pietist societies, continental revivalism and eighteenth-century evangelicalism in Dublin and in Ulster.20 The biographer of Peter Roe, whose own generation led an evangelical movement within the Church of Ireland, stated that ‘at the time Mr Roe commenced his clerical career, the Moravian Church was the body which seemed most alive to the Christian duty…of sending “portions to them for whom nothing was prepared”’.21

The year after Cennick’s first visit to Ireland in 1746 there arrived another English evangelical whose faith had also been influenced by the Moravians. John Wesley’s visit in 1747 was the first instalment of a 40-year commitment to the cause of Methodism in Ireland in which 21 visits were made, including his first to the province of Ulster in 1756.22 The small minority of historians who have followed the course of the Methodist revival in both England and Ireland in the eighteenth century have been struck by a remarkable difference of strategy and tactics employed by Wesley in the two countries. Whereas in England Wesley saw himself as having a special—but not exclusive—ministry to the poor, and frequently made barbed criticisms of the worldliness of the English Church and its gentry patrons, ‘in Ireland his mission worked downward from the gentry class and outward from the garrison in a way that would have been unthinkable in England’.23 The editors of the recently published and definitive edition of Wesley’s Journal st...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of figures

- List of maps

- List of tables

- Preface

- Part One: From international origins to an Irish crisis 1740–1800

- Part Two: Voluntarism, denominationalism and sectarianism 1800–50

- Part Three: Culture and society in evangelical Ulster

- Part Four: From religious revival to provincial identity

- Notes

- Bibliography