![]()

Part I

Evolutions of the Music Documentary

![]()

Chapter 1

Tony Palmer's All You Need Is Love

Television's First Pop History

Paul Long and Tim Wall

Introduction

The 2009 re-release of Tony Palmer's All You Need is Love: The Story of Popular Music, first broadcast in 1977, allows television scholars the opportunity to reassess the status of this long-neglected documentarist, and for those interested in popular music to consider Palmer's role both in its historiography and representation. Promoted on the DVD as “Tony Palmer's Classic Series,” its seventeen parts reproduced the long-form documentary approach of Kenneth Clarke's Civilisation (1969) or Alistair Cooke's America (1972–1973). Originally broadcast as prime-time commercial television in the UK, and sold to twenty-five countries, it was produced on a “Hollywood-scale” budget, in over forty countries, and the series featured over 300 musicians often in specially filmed performances.

Some reviewers saw the re-released series as a significant televisual and cultural moment, celebrating an “intelligent, adult treatment” of its subject and doubting that such a program would be commissioned today.1 Others saw the series as “laughably off the mark” in seeing various international rock artists as being the future of popular music, dismissing disco, and missing out on the then emergence of punk.2 Such evaluations are set in the context of a contemporary glut of programming on popular music and with the benefit of hindsight. Most importantly, none evaluate this ambitious and informed sweep of pop's past at a time when print histories of pop were only just emerging and television producers were first grappling with how to make long-form cultural histories.

| Figure 1.1 | Television's first pop history. |

In what follows, then, we first investigate Palmer's approach through the prism of the concluding scenes of the final episode of the series. We position him as pop television's first auteur, and examine the distinctive techniques of narrative and narration within this documentary series. Finally, we try to discern Palmer's core thesis on the organization of music culture in relation to art, to popularity, and to black culture.

Predicting the Future

All You Need is Love was first broadcast from February to June 1977, exactly mirroring the celebrations for the Queen's Silver Jubilee and the zenith of an attendant moral panic about punk focused around The Sex Pistols’ release of “God Save the Queen.” This conjunction reminds us that the most striking absence of All You Need is Love is the developed notion, common in Palmer's earlier work, that “pop” holds a revolutionary potential to critique the status quo. The importance of the emergence of punk as music and cultural revolution within post-1977 popular music histories, established in academic work by Dick Hebdige and Dave Laing,3 is the basis of the common critique of the series; that it is flawed for missing this major event. This is acutely evident in the final episode. Engaging with Palmer's treatise with something approaching the “condescension of posterity,” 4 Bob Stanley, for instance, asserts:

Disco is dismissed in less than a sentence. Kraftwerk are ignored in favor of Tangerine Dream. As for the rest (Black Oak Arkansas, Stomu Yamash'ta, Baker Gurvitz Army), it only seems proper to point out that hindsight is a fine thing. The series ends with a century of music flashing before our eyes to the soundtrack of Mike Oldfield's Ommadawn. When it was first broadcast, the Sex Pistols were simultaneously trashing their record label's offices, and pop was reborn.5

This notion that Palmer was in error to think that Oldfield epitomized the culmination of pop's history while it was being reborn elsewhere needs some interrogation itself. This is particularly important given that subsequent histories see the artists Palmer championed as the very ones that punk displaced. However, we want to argue that such critiques both misunderstand pop history, its televisation and how Palmer's series actually works as a meaningful text.

It is possible to construct a convincing argument that it is Palmer who understood the fundamentals of pop's development far better than his recent critics. If one looks beyond the now long-forgotten artists with whom Palmer was enamored, we are presented with a set of themes that convincingly anticipate the characteristics of twenty-first-century pop. These include the sorts of postconsumerist, collective, sustainable lifestyle music that is celebrated each year at the UK's Glastonbury festival,6 set side-by-side with pop as a producer's medium, slickly devised with scientific accuracy in studio technologies. Palmer establishes these themes and then juxtaposes them as an assertion of pop's paradoxical and manufactured character. Highly abstract, often “symphonic,” popular music is contrasted with highly personal styles, and stadium success is set against intimate retreat that, in turn, is placed aside the scale and majesty of nature. The last episode in particular highlights threads of music making which were to dominate popular music in a way punk never did. The numerous references to fusions of rock, folk, and “world music” now seem prescient, and while Palmer presents synthesizer-based, programmatic music as the product of the Muzak corporation and the Jingle Factory, as we now know, this method of music making became the basis of most post-1977 popular music genres from disco, electropop, rave, through to drum and bass, gabber and chill-out.

In this final episode these themes are personified in Mike Oldfield as a musician/composer/studio-manipulator producing a folk/world/rock hybrid using multitracked, postsong, programmatic structures. In the closing sequence of the series highlighted by Stanley, the full gallery of personalities from pop's past rush towards this present with increasing velocity, their images edited to the climax of Oldfield's “Ommadawn.” The moment is then frozen as Oldfield looks out into the wild openness of the future of music like the wanderer of Friedrich Caspar David's Romantic painting7 and we return to his studio as he contemplates the very smallest of additions to his multitracked masterpiece.

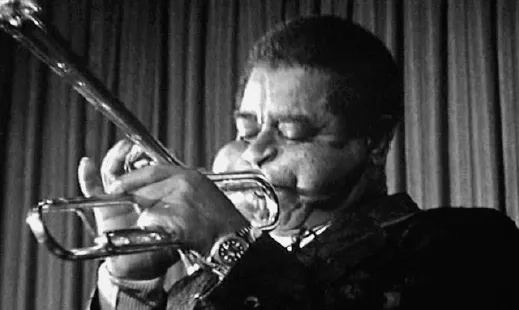

| Figure 1.2 | Excerpts from the final sequence of All You Need is Love. |

| Figure 1.3 | Excerpts from the final sequence of All You Need is Love. |

| Figure 1.4 | Excerpts from the final sequence of All You Need is Love. |

| Figure 1.5 | Excerpts from the final sequence of All You Need is Love. |

| Figure 1.6 | Excerpts from the final sequence of All You Need is Love. |

We do not present this argument to prove Palmer could predict the future, but to point out that the importance of All You Need is Love lies less in who he chose to represent, or in how successful he was in identifying pivotal moments in popular music history, but how he represents and engages us in the work of musicians as music makers and cultural agents. Palmer does not present a simple socially contextualized narrative of pop's breakthrough moments, and he certainly did not rely on consensus histories of pop, mainly because so few were available. Instead, he drew on approaches to documenting culture that he had established in his earlier work with more elite forms of art culture. As we discuss in more detail below, he also produced programs, which explore the potential of television as an agent of document, of investigation, and of intellectual engagement. At the same time, though, for all his interests in the genealogies of pop, we will argue that his central theses relied on received notions of cultural hierarchy which he applied to popular music, rather than comprehending pop on its own terms.

Treating Popular Music Seriously

The recent appearance of two studies of Palmer paradoxically serves to draw attention to the fact that this director's work has gone relatively unregarded in popular music historiography. In John C. Tibbetts’ exhaustive appreciation, All You Need is Love is identified as one of Palmer's crowning achievements,8 while Alison Huber has suggestively interpreted the series as an essay on memory.9 Nonetheless, the long ignorance of Palmer is curious given that he produced some of the landmark moments in popular music programming over the course of a decade. These include: All My Loving (1968); Cream “Farewell Concert” (1968); Rope Ladder to the Moon—Jack Bruce (1969); Fairport Convention & Colosseum (1970); 200 Motels—Frank Zappa (1971); Ginger Baker in Africa (1971); Bird on a Wire—with Leonard Cohen (1972); Rory Gallagher—Irish Tour (1974); Tangerine Dream—Live in Coventry Cathedral (1975); All You Need is Love (1976); The Wigan Casino (1977).

Palmer's first documentaries, mentored by Huw Wheldon for the BBC's Monitor (1958–1965) arts strand, were concerned with high art subjects such as Georg Solti and Benjamin Britten. He also gained contemporary renown as popular music critic for the UK's Observer from 1967 to 1974. His work offers an important resource for any examination of the representation and historicization of popular music. Palmer was instrumental in developing a serious critical appraisal of pop. His 1968 Observer review of The Beatles (“The White Album”) insisted that “Lennon and McCartney are the greatest songwriters since Schubert,” an appreciation reproduced on the sleeve of the soundtrack album of Yellow Submarine. This commitment was translated into his television work with All My Loving (1968), a film which exhibited a range of stylistic tropes established in his treatment of high art subjects for Monitor and which inform All You Need is Love. Palmer's position on popular music in 1968 was singular enough to warrant this contemporary evaluation from Tim Souster who suggested that the filmmaker-journalist was one:

who on the strength of a moderately successful film (success of course was inherent in its subject-matter) and of some pretentious writing in the Observer, has been endowed with a certain “authority.” For him, Pink Floyd outdo Cardew and Stockhausen in “modernity,” and even The Who's “Magic Bus” (an inferior reworking of their brilliant “Talking About My Generation”) puts Stravinsky's Symphony in Three Movements in the shade.10

To label All My Loving ‘moderately successful’ is to underestimate its impact and originality. Far removed from the simple ma...