![]()

Chapter 1

Ways of Thinking about Language

Introduction

In this book we are interested in human communication. This takes many forms, for example, spoken language, of which conversation is the most common; written language; signed language. These forms comprise many elements; conversation, for example, will consist of sentences, clauses, phrases, sounds and structured interchanges between the participants. The written form has sentences, words, spelling, punctuation and a particular shape on a page. Later in the book, some of the relationships between these are discussed. Our purpose is to draw attention to how communication is such a vital part of life and to think of the implications of a difficulty in this characteristic aspect of our social relationships. Here we will briefly introduce some of the main ideas of the elements of communication and start the discussions by looking at conversation.

Conversation

Conversation is the most common form of communication which takes place every day. The variety of conversation is infinite, through the whole range of face-to-face encounters and telephone communication. We only have to think of interactions between friends and family members, discussions between doctors and patients, teachers and pupils and members of boardroom meetings to realise how much it varies in its formality and style on each unique occasion. Indeed, in any situation where people are found, there will be conversation. Yet conversation requires highly developed skills.

How does a person learn how to have a conversation? What do they do? Stop for a moment and think what you do when you have a conversation. Think of all the things that you have to do. Perhaps also, try to observe some other people in conversation to see and hear what they do. You will need to observe with your eyes and with your ears.

Firstly, it should be said that for most people, their knowledge about how to have a conversation is quite unconscious. However, this largely unconscious knowledge, built up over years, affects the content and the management of the conversation, that is, what it is about, and how the conversation takes place.

Conversation always involves more than one person. It relies on signals made by the individuals when they ‘pass messages’ to each other, through speech sounds and other noises, words and phrases, facial expressions, gestures and other movements of their bodies. In successful conversations, there are not too many silences, neither are there too many overlaps of speech. For the most part, people know when it is their turn in the conversation. They know this from a variety of signs: the changes in the rise and fall of the voice of their conversational partner(s); the loudness of the voice; the direction of gaze and small changes in body position and in gestures. All of these help the speakers to cooperate with each other and to take turns to speak. If you have ever tried to have a conversation with someone whose eyes never meet your own, who never seems to pause to allow you to say what you want to say, or who does not pick up what you have said, you will know how difficult conversation can be. On the other hand, in most conversations, it would be unusual if the people spoke perfectly in turn and always waited for their partner to finish what they were saying. Perhaps more surprisingly, if the conversation was written down, or transcribed, exactly as it had been said, it would be unusual to find that the speakers had spoken in what might be described as ‘complete sentences’.

The Linguist’s View

Linguistics, the science of language, is concerned with classifying and analysing the features of language, how it is used and how it is structured. Linguists are interested in the components or levels of language. To look at language and communication in some detail, it can be broken down into its components and it becomes necessary to have some words to talk about what we are describing. First, two of the most commonly used terms used to discuss human communication are ‘speech’ and ‘language’. They are often used interchangeably although it is quite possible and indeed, common, to have language without speech, as in sign languages. Speech is only one form of language. It is a way of using the sounds of the human voice to communicate. We can also use writing, or signs. Speech is the audible (spoken) form of language.

Components of Language

For the purposes of discussion, in this book we will often refer separately to the components of spoken language. This might lead you to believe that speech sounds, grammar and meaning are unrelated to each other. A moment’s reflection about the way in which you use language at an interview, compared with, for example, when you are talking informally to a good friend, will probably alert you to the effect that the context and purpose of communication has on pronunciation and choice of words. The academic study of language is a very large field so that the separation of its components is probably inevitable. However, the sound, grammar and meaning levels operate together in our use of language. The components are therefore integrated and interdependent. Nevertheless, in order to examine the main components a little more carefully, we will consider them separately. We will consider the sounds, grammar and meaning.

The Sounds of Language

When referring to the sound components of a language, linguists usually distinguish between phonetics and phonology.

Phonology

The study of the capacity of speech sounds to change the meaning in language is known as phonology. Look at the list of words below and notice how the change of the vowel sound alone changes a word’s meaning:

beat, bit, bait, bet, bat, bought, boat, boot, butt, bite, bout, Bert.

(Adapted from Ladefoged 1982: 70)

If you read the list aloud, you will hear the vowels used in your particular way of pronouncing English, that is, your accent or regional variation. For interest, ask other people, including if possible, some foreign speakers, to read the list and notice the differences in the way they speak. Phonology examines the system or patterns of sounds used in language.

An everyday example of the exploitation of phonology can be found in the cartoon feature in a national newspaper, known as ‘Lost Consonants’. It draws its humour from the change in meaning which one consonant can make to a sentence. In many cases, this loss of a consonant means the loss of a sound and, as a consequence, a change in meaning. For example:

‘He was very fond of a tory at bedtime’

‘He finally found work as a long distance lorry drier’

‘To deter illegal parking, police introduced wheel lamps’.

(Rawle 1992)

Phonetics

It is important to remember that in English, the alphabet does not correspond to the sounds of the language and there are certainly more vowel sounds than ‘a’, ‘e’ ‘i’ ‘o’ and ‘u’. Sounds of speech do not always correspond to the letters of the alphabet or the way in which a word is spelled.

In order to write down sounds of a language and to avoid the complex spelling rules found in languages like English, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is used. This has a one-to-one correspondence between symbol and sound. For example, in English the last sounds in the words kiss and palace are written quite differently but would be written /s/ and /s/ phonetically; the sound at the beginning of fun and at the beginning and the end of photograph would also have the same phonetic symbol. Conversely, the words circus and comb begin with the same letter but would have to be written with a different phonetic symbol to convey the different initial sounds. The vowels in the words he, beat, sheet and key may sound the same but they are written differently. Analysis at the phonetic level considers the way in which sounds are made, how they differ and how they are similar.

Prosody

A final and important aspect of speech pronunciation is known as prosody. That is the stress, intonation and voice quality used in spoken communication. In English, intonation and stress can change the meaning of an utterance without changing the words. Say each of the following first as a statement and then as a question:

You’ve been working

The shop was closed

You think he’s good-looking

Next, say the first sentence as though you feel sorry for the person you are talking to. Say the second as though you are angry. Say the third as though you don’t believe ‘he’ is good-looking.

For all of the above activities it would be useful to tape-record yourself and listen to the result.

You can see that the variations in the rises and falls of your voice, the loudness of your voice, the speed of your speech and the emphasis you put on words or parts of words makes quite a difference to the meaning of what you are saying. Note that at no time did you change the words or the order in which you used them.

Grammar

The next way in which we may describe language is by considering the grammar or the rules by which the words and parts of words are put together. These rules will determine the ordering of words, so for example I saw her is acceptable in English but I her saw is not. The way in which words are structured to convey specific meaning is also governed by rules: The boy kick the ball is unacceptable but The boy kicked the ball or The boy kicks the ball is acceptable depending on the meaning the speaker wishes to convey.

Consider the following examples and try to say exactly where a rule is broken:

I playing football yesterday

I bought a pair of sock

In example 1, the ending -ing conveys the present tense of the verb play and so is incompatible with the word yesterday which suggests the past tense. In order to be acceptable the sentence should be I played football yesterday.

In the second example, the word pair indicates that the plural form of the word sock is required so that an acceptable sentence would be I bought a pair of socks.

The small parts of words which change their meaning, from singular to plural or from one tense to another, are known as morphemes and the study of this aspect of language is known as morphology. The ordering of words and parts of words is governed by the rules of syntax. Morphology and syntax make up the grammar of a language.

Meaning

Next, the choice of words and the function they perform will be an important aspect of the meaning of language. In the study of the meaning of language, semantics is the term used.

Much of the understanding of a word’s meaning comes from our knowledge of the linguistic and the social context in which it is used. Briefly, the linguistic context is the other words and linguistic elements which surround the word in question. In English, many words have the same written form but different meanings. Just consider different meanings of the word swallow; table; page. Further, words which are written differently can have the same pronunciation, for example, sole and soul; write and right. Unless you hear or read these words in the context of connected speech or written language you will not understand their specific meaning. The social context, that is, who is speaking and where they are, will be important factors in determining the choice of words used. This will influence the shared meaning, which is essential when considering how people understand each other.

Content, Form and Use

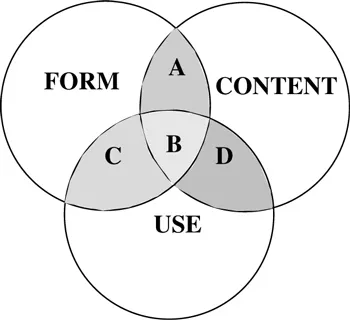

Our discussions above have focused on the complex and overlapping components or levels of human communication. In order to think about the very complicated system more simply, we can think of these components under three headings: the meaning or content of the communication, the structure or form and the function of the communication. Each aspect is essential for communication to be effective. Two American researchers, Lois Bloom and Margaret Lahey, have presented these ideas clearly by means of three overlapping circles (a Venn diagram) Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The intersection of content, form, and use in language (Bloom and Lahey, 1978)

Content refers to the topics and ideas that are put together or ‘encoded’ in messages. It reflects what we know about people, things, actions. The content of our communications shows that we are able to make relationships between ideas, to consider how things are similar, different and associated with each other. The content represents and allows access to concepts which are stored in our memory.

Form is the way in which meaning is represented. This may be through speech, signs, writing or another systematic form. It consists of an inventory of units, for example, sounds, marks on a page or movements, and the system of rules for their combination. In the context of spoken language these would be referred to as phonology, morphology and syntax.

Use has to be considered from two points of view: use or function, and context. Function refers to the goals of language, the reasons why people speak. Context refers to how individuals understand and choose among alternative forms for reaching the same or different goals. In linguistic terms, the functional level of language is known as pragmatics.

One of the strengths of Bloom and Lahey’s model is that it shows how aspects of language interconnect and yet can be identified separately. It shows how it is possible to explain that the language difficulties of an individual might arise from difficulties predominantly in one area or across more than one of these areas. However, the model cannot show that within each of these areas there are different theoretical frameworks which can explain and predict the functioning of that aspect of language. Further, within an area such as Form, the levels of language, syntax and phonology are studied in different ways. This is also the case for Content and Use. We will consider these later.

Language Development in Children

The brief outline of the features of language demonstrates the complexity of human communication, yet most children are skilled communicators by the time they go to school. By the age of five, the majority of children have mastered many of the rules of grammar, have a wide vocabulary and can make themselves understood to a range of people in a variety of situations. Their language development is not complete; indeed, communication skills continue to develop throughout life, but the main features are in place. In this book, we can only give a broad account of how children learn to communicate. It is important that practitioners who are concerned about children’s language should be clear about patterns of development and about the main influences on this development. Further reading can be found in the list at the end of the chapter.

What is it then, that a child has to develop to become an effective communicator? What has to be available and what does the child have to do? It is helpful to consider these questions because, if we can identify what usually happens, then we may begin to understand why some children experience difficulties in learning to communicate. First, what does the child have to learn?

We noted above that conversation can only take place when there are at least two people. A child usually becomes aware of this very early in life through the contact with attentive adults. Adults frequently talk to young babies as though they understood every word and it is thought that these early contacts enable the child to ‘tune in’ to the sight and sound of people. There is evidence that in the first few weeks of life babies start to prefer the sound of familiar human voices over other, non-human sounds and they quickly learn to recognise familiar faces (Bower 1980). The sounds made by infants are often stimuli for ‘conversations’ with adults. An adult will often pick up and imitate a baby’s gurgles and coos and begin the early turn-taking which is later an important element of conversation (Richards 1974). It seems as though the foundations for communication are laid very early.

It can be very difficult to determine the exact time when a child uses its first real word, indeed, in some ways, the first word ...