- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The most effective way to understand what a child knows about the reading process is to take a running record. In Running Records, Mary Shea demonstrates how teachers can use this powerful tool to design lessons that decrease reading difficulties, build on strengths, and stimulate motivation, ensuring that children develop self-sustaining learning strategies.

Special Features include:

- a step-by-step outline for taking efficient running records

- guidance in running record analysis: readers will learn how to use running record data to determine a child's level of decoding skill, comprehension, fluency, and overall reading confidence

- a Companion Website offering videos of the running record process, sample running records for analysis, and numerous other resources

In order to meet the multi-faceted needs of children in today's classrooms, teachers must be knowledgeable about literacy concepts. Running Records provides that invaluable knowledge, making it an ideal text for literacy courses for pre-service teachers and a key professional reference for in-service teachers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Running Records by Mary Shea in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Rationale for Running Records

Meeting the Diverse Needs of Learners

1

INTRODUCTION—DIFFERENTIATING INSTRUCTION

Responsive Teaching Informed by Ongoing Assessment

Big Ideas

Problem with standardization

Inclusive teaching for achievement of learning goals

Differentiated instruction

Differentiating content, process, product, and environment

Assessment that supports instructional differentiation

STANDARDIZED INSTRUCTION WITH NONSTANDARD STUDENTS

Ohanian (1999) exposes the fallacy of working with a standard timetable in classrooms with gloriously nonstandard kids. Different experiences, background, interests, motivations, talents, cultural heritage, and other factors have shaped their uniqueness—their nonstandardess. She emphasizes that “one size [curriculum] fits few” in schools today (Ohanian, 1999).

Effective curriculum planning considers the identified and potential needs of all students, balancing excellence of content and equity in delivery with assessment that continuously informs instruction for each learner. Such curriculum outlines a process for meeting state standards across diverse populations (Fahey, 2000). Programs that disregard diversity—favoring standardization in instruction, materials, and products—are least likely to ensure that all children learn. Sadly, many are left behind (Tomlinson, 2004) when teachers are required to implement programs in standardized ways rather than teach children.

Key Concepts

Standardized instruction: uniform, scripted lessons used to ensure that all teachers conform to an accepted mode and time-line for content presentation.

Nonstandard: unique; having individual qualities across a variety of spectrums.

INCLUSIVE TEACHING FOR UNIVERSAL LEARNING OF CURRICULUM

Tobin (2008) describes the universal design curriculum model as one that includes instructional differentiation (responsive teaching) at all levels. Such instruction must be tied to immediate, in-the-moment assessment to be effective. In the current classrooms of diversity, responsive teaching is essential for success. Most students are able to benefit from initial instruction that’s learner-centered. But, some don’t. In such cases, in-the-moment assessment is essential. It reveals differences in interests, background knowledge, or needs and expedites the recognition of any learning glitch; it informs instruction that ameliorates the situation (Shea, Murray, & Harlin, 2005).

When learning is interrupted, teachers act in intelligently eclectic ways (Smith, 1983); they carefully consider students’ individual strengths and needs before selecting an intervention that provides a different route to the same learning outcomes. They use authentic assessment to observe learners in a full performance of target behaviors; data gathered help them decide what the learner has confused, which materials are appropriate, and/or the best approach for teaching this child. Good teachers efficiently implement planned and in-the-moment responsive teaching based on data gathered; they make content and/or skills accessible to learners who were previously nonresponsive (not learning). When their interests and needs are aligned with learning opportunities, students perceive curricular outcomes as achievable (Pettig, 2000).

Key Concepts

Inclusive teaching: instructional approach that includes a range of appropriate strategies, ensuring that all children have an opportunity to learn.

Universal design: an approach for designing units of study that considers the what (content), how (strategies), and why (affect) of learning in ways that consider individual learners’ needs.

Differentiation: appropriately adjusting the content, process, product, and the environment in a learning event to enhance students’ opportunities for success.

Responsive teaching: instruction that includes ongoing assessment and responds immediately, adjusting instruction to fit the learner’s expressed needs, strengths, or interests.

Eclectic: selecting from appropriate options the instructional approaches and resources best suited for individual learners.

PROACTIVE DIFFERENTIATED INSTRUCTION: INCREASING ACHIEVEMENT FOR ALL

“Differentiation embodies the philosophy that all students can learn—in their own way and in their own time” (Dodge, 2005, p. 6). Differentiated instruction (responsive teaching) focuses on curricular outcomes, helping all children meet and exceed established standards (Tomlinson, 2000). But, it starts with the child—and the teacher—not the content (Dodge, 2005). Kusuma-Powell and Powell (2004) identify the knowledge and skills that teachers need to hone for successful differentiating.

- Thorough understanding of students’ strengths and needs. To establish appropriate objectives teachers must know the learner, specifically what he knows and can do at any time (Littky, 2004). This requires authentic, ongoing assessment of learning (summative assessment) and for learning (formative assessment) (Stiggins, 2002; Shea et al., 2005)

- Knowledge of the scope and depth of curricular content. Teachers need to set learning goals that are grounded in the curriculum; lessons are crafted in ways that engage students in meaningful, developmentally appropriate tasks (Tomlinson, 2008). Instruction follows careful analysis of assessment data gathered from classroom activities (Shea et al., 2005).

- Knowledge of best instructional practices and expertise in using them (e.g. flexible grouping, student choice, wait time, effective feedback).

- Skills in collaborative planning, assessment, and reflection.

At the center of any effectively differentiated classroom—one where the teacher teaches responsively—you’ll find sound theoretical, research-based practices implemented by a teacher with a broad repertoire of instructional skills and professional knowledge (Silver, Strong, & Perini, 2001; Tobin, 2008). These teachers assess each child’s readiness (background knowledge on the topic and specific skills), talents, interests, motivation, and other factors; they assess children’s performance on meaningful tasks directly related to the instruction provided. They blaze trails toward success on curricular outcomes by adjusting one or more areas of lessons. They differentiate content (what students learn), process (how they learn it), product (how students demonstrate content mastery), and environment (conditions that set the tone and expectations) (Tomlinson, 1999; Tomlinson & Strickland, 2005) depending on the needs they’ve identified through assessment.

Key Concepts

Summative assessment: assessment at the end of a teaching event (i.e. at the end of a unit of study). The assessment tool can be teacher made or a publisher’s product.

Formative assessment: ongoing, in-the-moment assessment during the teaching of a lesson or unit.

Developmentally appropriate practice: a framework of principles and practices matched to the cognitive, social, and emotional level of learners.

DIFFERENTIATING CONTENT

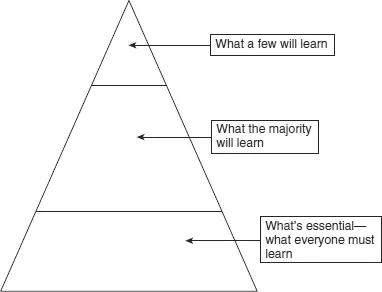

Schumm, Vaughn, and Leavell (1994) offer a model, The Planning Pyramid, which outlines how to “plan for inclusionary instruction and meet the challenge of content coverage in general education classrooms for students with a broad range of academic needs” (p. 609). It’s based on the principle that less is more—more time to uncover content using resources that students can and want to use. The pyramid allows teachers to distinguish what content all students must know.

This core becomes the focus for meaningful, differentiated instruction. There’s also a sizable body of content most will learn anyway when presented in interesting and accessible ways. Based on interest and motivation more than ability, particular topics stimulate learners to delve deeper into content only some will learn (Shea, 2006). There is ample time to differentiate instruction, use time and space differently, continuously assess students’ performance, and provide timely feedback when we put textbook content in its proper place on the pyramid (Shea, 2006; Tomlinson, 2001; Yatvin, 2004). Paths to the content at each level of the pyramid must be matched to the learners who travel them. Authentic assessment allows the teacher to create an effective path to core curricular standards—one well matched to the learner’s interests and needs.

Figure 1.1 The Planning Pyramid: Levels of Content Learning for Unit of Study

Source Adapted from Schumm, Vaughn, and Leavell, 1994

Key Concept

Authentic assessment: measuring students’ learning or skill development in the applications or performance of each in real world (authentic) tasks.

DIFFERENTIATING PROCESS

Children’s interests, preferred ways of learning, and readiness influence the process (e.g. tasks and materials used) for their learning (Tomlinson, 1999). Vygotsky’s (1978) theory proposes that learning is facilitated when the tasks children are expected to accomplish fall within their zone of proximal development. That zone is defined by what a learner can do with the help of a competent person (adult or peer), but cannot do alone. Teachers scaffold students’ performances while they’re in a zone (e.g. while learning a concept or skill), but teachers also need to scaffold learners through that zone (Dodge, 2005; Drapeau, 2004) and into the next level. The amount of scaffolding adjusts according to the child’s changing needs and abilities (Berk & Winsler, 1995). Instruction in the zone is just right with regards to complexity, clarity, interest, and motivation. Tasks and materials are not too easy, creating boredom; they’re neither too hard, causing frustration (Tobin, 2008).

Sousa (2001) concludes that moderate challenge is necessary for optimal learning. There’s little satisfaction from accomplishing a mindless (without effort or thought) task aside from the fact that we got it done. But, a moderately challenging task requires a degree of preparation. We’re ready to do it. Readiness (e.g. background knowledge and prerequisite skills) for a given task establishes the current range of the child’s zone for it; readiness is determined by careful teacher observation and ongoing assessment (Allan & Tomlinson, 2000; Dodge, 2005; Vygotsky, 1978).

Tasks are designed to make concepts and skills in the zone accessible as well as appropriately interesting and challenging for students. This strengthens their self-esteem and motivation—essential ingredients related to improved learning and performance (Cruickshank, Brainer, & Metcalf, 1999; Murray, Shea, & Shea, 2004). Another factor in a Vygotskian learning framework is the concept of options; children make some decisions—within parameters of course—in a social contract model of learning. Pettig (2000) concludes, “choice validates a student’s opinion and promotes self-efficacy” (p. 16).

DIFFERENTIATING PRODUCT

Children have options for how they will show what they know; differentiated products (e.g. journal entry, drawing, performance) demonstrate attainment of learning outcomes. Children’s work samples reflect the multiple routes they’ve taken to reach curriculum outcomes while validating their understanding of core content (Tobin, 2008). Allowing children to decide how they’ll demonstrate understanding honors individual interests; it increases students’ engagement. Learners are more likely to take responsibility for choices made in a classroom where the tone implies respect for their ideas (Bess, 1997).

A CLASSROOM WITH A DIFFERENTIATED VIEW

A sense of community is quickly recognized in a differentiated classroom. It’s an environment where students and teachers collaborate; it’s safe to try or ask for help. And, there’s an expectation that all can achieve (Tomlinson, 2001).

Fairness (equity) is redefined in the differentiated classroom; it’s distinguished from the equality of sameness for all. “Fair means trying to make sure each student gets what she needs in order to grow and succeed” (Tomlinson, 2001, p. 23). It’s difficult to address assessment, content, process, product, and the environment at once. That’s why teachers typically start with one or two of these areas (Tomlinson & Strickland, 2005). However, assessment remains at the hub of the wheel; effectively observing and recording what learners currently know and can do is central to effectively differentiating in the other areas.

GETTING STARTED ON DIFFERENTIATING

Effective differentiation is complex (Tomlinson, 1999); but, researchers offer general principles to guide the process.

- Focus on the essential, core knowledge and skills in the content, creating paths for all to reach the same content standards (Pettig, 2000).

- Plan lessons based on diversity factors identified in the classroom (e.g. readiness, interest, ability, culture, language).

- Continuously monitor and document progress with meaningful assessments. These should incorporate authentic application of skills (e.g....

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Rationale for Running Records Meeting the Diverse Needs of Learners

- Part II Running Records Step-by-Step Assessment that Informs Differentiated Reading Instruction

- Part III Digging Deeper Reading Performance Reveals Process and Product

- Part IV Differentiating Instruction Based on Data from Authentic Curriculum-Based Measures (Running Records)

- Bibliography

- Index