![]()

Part I

THE SYSTEM

![]()

1

SEEING STARS

Janet Staiger

Having studied film history for little more than five years, my first tendency, like so many youth in any field, is to presume that the older histories are wrong. Revisionist history has, I am sure, as much to do with the Oedipal complex as it has to do with changing ideological conditions which position those of us in more recent times to see facts in new ways. Of interest, then, to me is that the more I study US film history, the more I realise that the older histories are less wrong than I used to believe they were. Often, the problems I have with them are not so much in fact but in emphasis, or more precisely, in the theoretical assumptions that have determined their choice and arrangement of those facts.

Much work on film historiography has been done recently.1 What I would like to contribute here is a gesture towards our new histories of film. I am interested in reasserting the value of background study, of study of adjacent facts in understanding events in the area upon which we are focusing. I am concerned that related histories become requisites in any study of film. I also find of interest the effect that a detailed chronology with careful dating of events can have on the representation of the events and their significance. Take, for instance, the standard representation of the appearance of the star system in the US film industry. Both a fuller set of dates and facts and an analysis of the concurrent theatrical scene can significantly alter our version of its appearance and development.

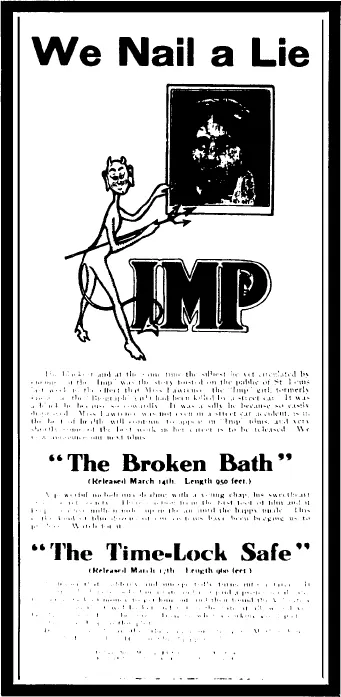

David A.Cook in the most recent extensive history of film repeats the story that in 1910 Carl Laemmle’s promotion of Florence Lawrence led to the star system.2 The reputed reason was Laemmle’s competitive move as an independent to take business away from the Patents Trust. Cook is relying on Lewis Jacobs’ and Benjamin B.Hampton’s histories. Jacobs’ version is the more descriptive. Mentioning the movie audiences’ attraction to some of the players, Jacobs posits that the Trust manufacturers ‘diligently kept [the player’s identities] secret, reasoning that any public recognition actors received would inspire demands for bigger salaries’. Laemmle, however, lured Lawrence from Biograph to IMP through an increased salary and promises of publicity. IMP’s advertisement in the Moving Picture World of 12 March 1910, that an earlier story of Lawrence’s death was a lie marked a clever publicity gimmick launching her name and film career as a star. Jacobs then comments that other independents began promoting their players by name while the licensed firms held back. While Jacobs notes that ‘Vitagraph, Lubin and Kalem were the first of the licensed groups to adopt the star policy’ (withholding the dates of their move to this), he writes that Biograph finally ‘was forced into line’ in April 1913. Jacobs notes the methods of publicising the new stars: trade photographs, slides, posters in lobbies, ‘star post cards’ and fan magazines. The latter began with Vitagraph: J.Stuart Blackton financed the Motion Picture Magazine. (Again, Jacobs supplies no clear date except to note that in October 1912 one writer requested stories about independent players as well as Trust ones.3)

Hampton’s account, although less dramatic, is similar—except that he sees Mary Pickford as the pivotal personality. Declaring ‘Little Mary’ as probably ‘the first player ever to register deeply and generally in the minds of the screen patrons’, Hampton argues that the independents had ‘more faith in the box-office appeal of individual players’ than a skilled presentation of a story such as D.W.Griffith’s work for Biograph. In his account, Hampton stresses IMP’s hiring of Pickford at double her Biograph wages and ‘movie patrons soon learned that “Mary Pickford” was the name of the actress they had enjoyed so much in Biograph films’. (Again, no dates.) While Hampton notes that the ‘star system had operated on the stage for more than a century’, he asserts that a great distance existed between legitimate theatre and the movies. Because of the exceptional profitability from low-cost film exhibition, the use of personalities had not previously been part of the ‘calculation of possible larger revenues’. Furthermore, the film industry exploited its perceived link with the masses: audiences knew film stars by their first names rather than the more austere Mrs Fiskes of the stage. Hampton discredits the assertion that the independents had better business acumen than the Trust manufacturers; he writes that everyone in the business was surprised by the ‘almost hysterical acceptance of personality exploitation’.4

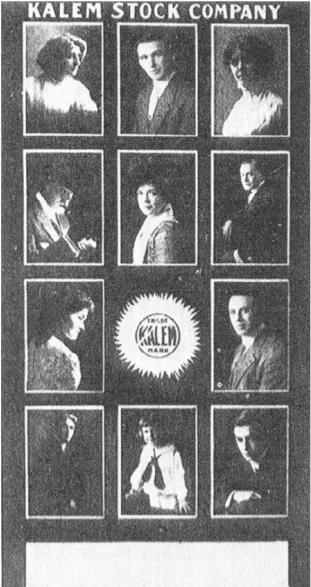

One other history of the star system’s appearance is worth reviewing before we analyse these accounts. Anthony Slide has meticulously combed through early trade material to determine ‘the first film actor to be recognised by the trade press’. He finds a story about Ben Turpin in the 3 April 1909 issue of Moving Picture World, an article on Pearl White in 3 December 1910 and a full page on Pickford three weeks later. Slide’s interest is in part in whether the actors and actresses might have wanted their identities kept secret because of the stigma of working in the lowly movies. Slide refers to Robert Grau’s allegation that most of the film players were not of the upper ranks of legitimate theatre but from ‘provincial stock companies’. In addition, Slide dates Kalem’s and Vitagraph’s publicising of their players’ identities. In January 1910, Kalem innovated ‘a new method of lobby advertising’: the company was making available to exhibitors posters with stills of the players and their names. Vitagraph exploited their players through public appearances, with Florence Turner live on a Brooklyn stage in April 1910.5

Figure 1.1 Moving Picture World, 12 March 1910

Figure 1.2 Moving Picture World

Several observations can be made about these histories. For one thing, both Jacobs’ and Hampton’s discussions are parts of larger arguments. In the case of Jacobs, he is attempting to explain the eventual demise of the Patents Trust. His explanation hinges on a neo-classical economic model: the independents were better competitors, innovating product differences which won out over more conservative business practices. Hampton is generally in the same model although he tends to credit the independents with more direct contact with their consumers’ desires. Hence, they were better able to gauge public preferences. For both historians, it is in the interest of the larger arguments to credit the independents with the innovation of personality exploitation. Slide is also constructing an argument but not one which revolves around the Independent-Trust competition. He wishes to disabuse us of the conception that either faction prohibited name recognition. His implicit intervention seems to be against Jacobs’ assertion that the Trust held back on the promotion of its players.

Figure 1.3 Moving Picture World, 15 January 1910

Besides the clear garnering of particular facts to support a larger position, these histories are notorious in their failure to compare dates (and sometimes even to give them). Such an ‘unspoken’, as Pierre Macherey would note, is symptomatic: dating and comparing dates might become problematic to the arguments.

Furthermore, less symptomatic but rather a practical factor in any writing of large histories is these histories’ gaps regarding the background both Hampton and Slide allude to but do not explore—the theatrical star system. Failure to discuss this impairs our comprehension of this important change in the US film industry. The questions then are, what do we learn when we review the events in the related field of the stage? And what happens when we start dating events and comparing them with the ones supplied?

Alfred L.Bernheim’s economic history of the legitimate theatre can be a start in supplying the background information we need. Writing in 1929, Bernheim sets out four phases of the US theatre’s economic structure through the 1920s. In the earliest years, a ‘stock system’ typified the theatre. Numerous permanent groups of players were attached to specific theatres where they played most of the season. Leads often changed with the rotation of the play repertoire of the company. About 1820, the ‘star system’ started. Here a theatre advertised a particular player more than the plays. Moreover, the stars, at first famous foreign actors and actresses, travelled across the country for limited special engagements. A result of the star system was devaluing the local stock players to supporting roles and diminishing the stock players’ salaries to provide funds for the stars. Stock companies further declined when the stars began travelling with their own companies. Bernheim dates this ‘combination system’ as securing economic dominance in the mid-1870s. The stock system almost vanished.6

The last phase was the ‘syndication’ of the theatre business. As combination companies ruled the theatrical stages in the US, efficient booking and distribution between engagements became essential for profit-making. Circuits of theatres developed along which companies regularly travelled. Taking advantage of this, booking agencies supplied the contacts between individual circuits and the attractions. In August 1896, three agencies (Klaw &; Erlanger, Hayman & Frohman and Nixon & Zimmerman) formed the Theatrical Syndicate. It asserted a monopoly control through contracts demanding exclusive use of its services by both the entertainers and the theatres. Similar to the upcoming battle between the Patents Trust and the independents in the film industry, not all members of the theatre industry were willing to submit to the Syndicate’s terms. The Shuberts (another agency) joined forces with notable independents such as David Belasco and the Fiskes.7

Through the 1920s, various battles and truces typified the relations between the two alliances. Occasionally one or the other sought to improve its share of the market, and after a flurry of acquisitions or losses, the two leaders settled into a suspension of hostilities. One period of intense competition occurred between spring 1909 and 1913. While the giants fought, the industry noted a resurgence of stock companies formed by those frozen out of the two alliances. In 1908, trade papers reported over 100 active stock theatres in various cities.8

Bernheim notes that the problems of the star system, syndication and the reappearance of the stock company were commonly discussed in the period trade papers. Not an observation by later historians, these difficulties were widely known by the participants.9

With this background, let me add a few more facts and set what is known into a more complete chronology. The Edison Company seems to have been one of the earliest and most aggressive companies to promote their players. In September 1909, Edison’s publicity paper to exhibitors announced that while others tried to bring out ‘some new press story’ about their ‘stars’ lives’, Edison knew that it had secured ‘some of the best talent the theatrical profession affords’. In its ‘stock company’, it had ‘under contract actors from the best companies in the business, companies such as Charles Frohman, David Belasco, E.S.Sothern, Ada Rehan, Otis Skinner, Julia Marlowe, Mrs Fiske, the late Richard Mansfield’. Subsequently, Edison introduced in its catalogues its stock players with individual lengthy descriptions of their prior experiences and stage successes.10

A couple of points can be noted about Edison’s publicity move. For one thing, the film industry was barely fourteen years old. It was just experiencing its first real spurt of expansion. The nickelodeon boom, which Robert C.Allen dates as developing about 1906–7,11 had only recently supplied enough capital growth to support widespread investment in large, permanent staffs. Individual cameramen shooting scenics, topicals and set vaudeville acts had typified the industry up to about 1907. Although companies shot narratives, these were generally chase films and were short: five to fifteen minutes. While some firms such as Vitagraph and Edison had used actors, player employment seems to have been temporary and occasional. Better stage players from the legitimate syndicates or provincial stock companies could hardly ...