CHAPTER 1

The legacy of the nineteenth century

THE RISE OF SOCIAL ARCHITECTURE

The nineteenth century, when Britain came to rule half the world. was a time of massive industrialization and urbanization. The growth of empire abroad and of great cities at home brought with it wealth for the few. For much of the population it brought exploitation, poverty, overcrowding and squalor. Gross inequality and harsh treatment were the hallmarks of Victorian Britain. But the misfortune of the many also brought forth the seeds of social movements that attempted to improve the lives of industrial workers and the urban poor— initiatives.that were to bear their fullest fruits in the twentieth century. Among these movements, attention was given for the first time to the application of architecture—of good design and construction—to social purposes.

The history of architecture has traditionally been seen solely in the legacy of important buildings—temples and cathedrals. palaces and mansions, civic buildings and cultural institutions—the icons that spelt out the development of the great styles of Western architecture. Although historians analyzed these landmarks in painstaking detail, only rarely did they lower their gaze to the mass of everyday buildings that surrounded them—the homes and workplaces of ordinary mortals; these were, quite simply, not architecture. This was partly disdain for the humble and vernacular, partly a reflection of historical fact: design was largely the prerogative of the rich. The holders of wealth—princes and merchants, the institutions of Church and State—were the patrons of the arts. The artists and architects served the wealthy. Slowly, during the nineteenth century, this situation began to change. Once the sole preserve of the rich and powerful, architectural skills began to be used for the benefit of poorer members of society.

The pioneer

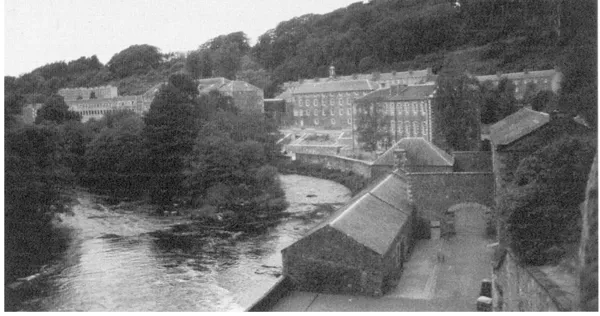

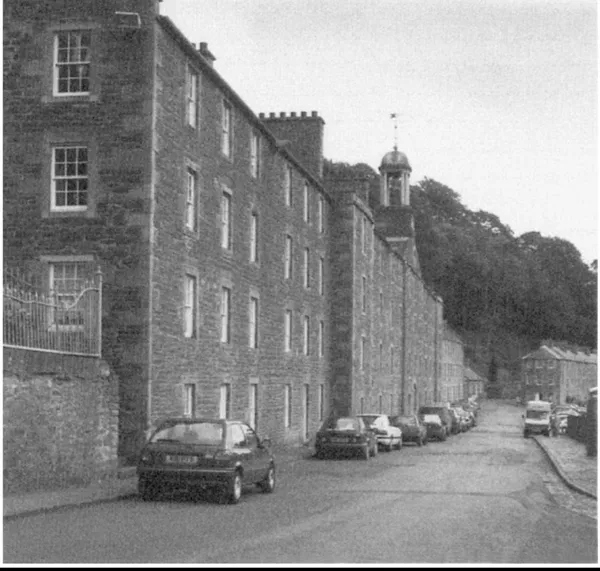

Perhaps the earliest example of social architecture was the work of Robert Owen (1771–1858) at New Lanark in Scotland (Fig. 1.1). In a narrow valley of the fast-flowing upper reaches of the river Clyde, New Lanark was founded in 1784 by banker and industrialist David Dale. Dale brought to his newly built cotton mills orphans from workhouses, and destitutes displaced from the land. By 1796 Dale employed 1,340 workers, more than half of them children as young as six, who worked in the mills for 13 hours a day. Today, such conditions truly evoke the “Dark Satanic Mills” immortalized by William Blake. Yet by the standards of the time Dale was one of the more enlightened employers.

Robert Owen, a Welshman who had made his fortune in Manchester, bought New Lanark from Dale in 1800 and set about building a model community. In the mills he established a regime that was firm but fair, and set up a pension fund, levied on wages, for the sick and old. He built a school for the children, taking them out of the mills and into full-time education from the age of 5 to 10. He built the Institute for the Formation of Character, where workers attended morning exercise classes and evening lectures. He built a co-operative grocery store, a bakery, slaughterhouse and vegetable market. He organized refuse collection and a communal wash-house. He improved the existing houses and built new housing to standards well ahead of the time, with large rooms, well lit and solidly constructed. The houses were a mixture of two-storey cottages and four and five-storey tenements (even then, multi-storey flats were a common form of housing in Scottish cities). Housing was built in a plain style from locally hewn grey stone. The public buildings were a little more elaborate, designed in a pared down classical style.

Figure 1.1 New Lanark, the Scottish industrial settlement where Robert Owen conducted his pioneering experiment in enlightened social provision and co-operation.

New Lanark was an experiment in social progress, although it was by no means a democratic exercise. Owen was noted for autocratically imposing on his workers his own ideas for their self-improvement. He sought to prove that a good environment could mould a healthy individual with stronger character; that a well treated work-force was a productive one. And his experiment was an economic success, showing steady profits and increasing value. The many thousands of visitors who flocked to New Lanark during Owen’s 25 years in charge came not just to see the social facilities but, no doubt, to learn what enlightenment could do for their own self-interest. What Owen practiced, he preached at length. Later in his life, in his writings and speeches, Owen formulated many of the ideas that were to form the basis of the co-operative and trade union movements. 1

Although Owen’s ideas became widely influential, his foundation could not provide a physical model for what was to follow. New Lanark was a small community, never larger than 2,500 people. The mills of the early industrial revolution were dependent on water power and many were sited in steep and inaccessible valleys, with strict limits on their potential for expansion. Early in the nineteenth century, the development of steam power freed industries from the valleys. Long before Owen left New Lanark, the stage was set for the most massive upheaval in social geography.

Urbanization

Between 1800 and 1850 the population of England and Wales more than doubled and the number of households increased by 135 per cent. At the turn of the century 80 per cent of people still lived in the countryside or in small settlements. By 1851 over half were living in cities and 25 per cent of the population was packed into ten urban areas with a population of 100,000 or more. Much of this development took place around London, but growth was most rapid in the industrial cities of the north. During this period Glasgow’s population more than tripled. In a single decade between 1811 and 1821 Manchester grew by more than 40 per cent. In the decade from 1821 Liverpool and Leeds grew at a similarly rapid rate.2 The development of the railways from the 1830s only served to accelerate urban growth.

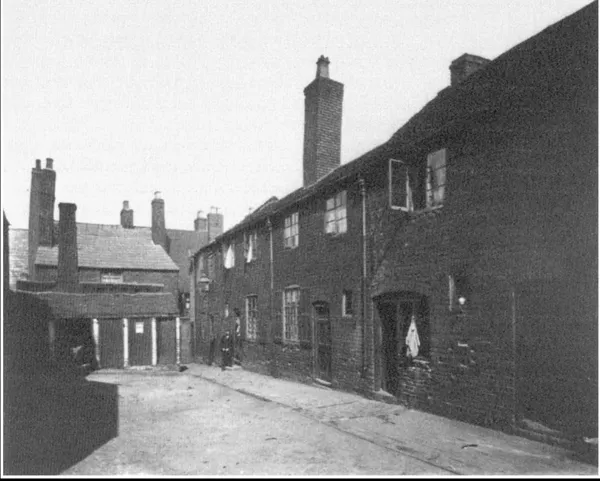

The urbanization of Britain has no parallel in terms of its scale and speed, and the effect on housing standards was disastrous. By the time Engels and Chadwick conducted their influential surveys in the early 1840s, much of the urban population was living in the most appalling conditions. A great deal of urban working-class housing was provided by the now notorious “back-to-backs”. “An immense number of small houses occupied by the poorer classes in the suburbs of Manchester are of the most superficial character” reported Chadwick, “The walls are only half brick thick…and the whole of the materials are slight and unfit for the purpose…They are built back to-back; without ventilation or drainage; and, like a honeycomb, every particle of space is occupied. Double rows of these houses form courts, with, perhaps, a pump at one end and a privy at the other common to the occupants of about twenty houses”.3 Thousands of these back-to-backs were built throughout the cities of northern England. Mostly they were two rooms about 12ft × 10ft built, “one-up, one-down” in two-storey terraces. Some also had a third storey, some a cellar beneath (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 A back-to-back court in Birmingham, photographed at the turn of the century.

Bad as they were, at least the back-to-backs provided families with the privacy of self-containment. Many lived in much worse conditions. Much urban housing was adapted. “Tenementing” was common—larger houses built for better-off families were divided up, let and sublet. Whole families lived in one room sharing such toilet and cooking facilities as there were. Many older houses became common lodging houses where letting was by the bed rather than by the room. Six or seven strangers might share a single room, with no furniture other than bare mattresses, Men were mixed with women, couples and families with single people. Often the beds themselves were shared, their users taking turns to sleep in shifts. Tenements and lodging houses could be found in all cities, but were most numerous in London where the slums they created reached into the heart of the metropolis. Soho, Westminster and Covent Garden contained areas of lodging houses—or “rookeries” as they were then called—as well as more outlying areas.

Worst of all were the cellar dwellings. Poorly ventilated, poorly lit—sometimes without windows at all—cellars were always damp. Many were just bare earth or partly paved, and poor drainage often caused them to flood. Insanitary and often grossly overcrowded, cellars offered the barest form of shelter to the most destitute of the urban poor and were often a breeding ground for infectious diseases such as typhus. Throughout the older industrial towns thousands of families lived in cellar dwelling, but they were most prevalent in Manchester and Liverpool. Engels estimated that, in 1844, 40,000–50,000 people lived in cellars in greater Manchester, while in Liverpool 45,000 subsisted in cellar dwellings— more than 20 per cent of the city’s population.4

Small wonder that such conditions led Engels and Marx to prepare their revolutionary treatise. In the Communist Manifesto, first published in 1848,5 they declared “The bourgeoisie has subjected the country to the rule of the towns. It has created enormous cities, has greatly increased the urban population as compared with the rural and has thus rescued a considerable part of the population from the idiocy of rural life” and proposed a “Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of the distinction between town and country, by a more equable distribution of the population over the country.” But Marxism had no immediate impact and was never to have significant influence in urbanized industrial countries. More immediately two strains of reform started to develop during the 1840s. In the cities the emergence of the philanthropic movement and the beginnings of legislative control slowly began to try to improve life. On the other hand, many rejected the evils of the city altogether and proposed a return to the idyll of rural life.

Flight from the cities

The earliest practical attempt to rescue working people from the evils of the city was the Land Company founded by the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor. The Chartists were mainly concerned with pressing for electoral reform and, in particular, the abolition of the property qualification for the franchise. Very few workers owned their homes at that time and the vast majority were thus deprived of the right to representation. As a working-class organization the Chartists were also concerned at the dire working and living conditions of their supporters.

In 1843 O’Connor attacked the evils brought by machinery and sought independence for the victims of the industrial revolution from employer and landlord. He proposed life on the land as a way out of the new industrial society. He planned to build 40 “estates” providing 5, 000 families with a cottage and a smallholding from which they could earn a living and, in pursuit of Chartist aims, the entitlement to vote. Each estate would have its own community centre, school and hospital. In 1845 he formed the Chartist Co-operative Land Society to carry out the plan. O’Connor sought the support of Marx and Engels, but they disapproved of all forms of private property and saw in this a diversion from their revolutionary aims.

But it did catch the imagination of a large section of the urban working class. By 1847 the Land Company had 60,000 members with 600 branches in England, Scotland and Wales, mostly drawn from the skilled section of the working class. Each member held 2 or 3 shares at £2 10s. Like an early version of the football pools, these shares would entitle them to enter a lottery for a smallholding and an escape from urban life. The first estate was started at Heronsgate (or O’Connorsville) near Rickmansworth. In 1845 the Company completed 35 cottages built in semi-detached pairs, each in its own smallholding of 2, 3 or 4 acres. 1, 487 members had sufficient shares to qualify for a homestead, and a ballot was drawn for the winners. Over the next three years a further five estates were started in Worcestershire, Gloucestershire and Oxford shire. 250 houses were built, as well as schools and community buildings. The houses were designed by O’Connor himself, often as homes and farm buildings combined (Fig. 1.3). They were built from O’Connor’s sketch...