eBook - ePub

Prologues to Shakespeare's Theatre

Performance and Liminality in Early Modern Drama

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prologues to Shakespeare's Theatre

Performance and Liminality in Early Modern Drama

About this book

This eye-opening study draws attention to the largely neglected form of the early modern prologue. Reading the prologue in performed as well as printed contexts, Douglas Bruster and Robert Weimann take us beyond concepts of stability and autonomy in dramatic beginnings to reveal the crucial cultural functions performed by the prologue in Elizabethan England.

While its most basic task is to seize the attention of a noisy audience, the prologue's more significant threshold position is used to usher spectators and actors through a rite of passage. Engaging competing claims, expectations and offerings, the prologue introduces, authorizes and, critically, straddles the worlds of the actual theatrical event and the 'counterfeit' world on stage. In this way, prologues occupy a unique and powerful position between two orders of cultural practice and perception.

Close readings of prologues by Shakespeare and his contemporaries, including Marlowe, Peele and Lyly, demonstrate the prologue's role in representing both the world in the play and playing in the world. Through their detailed examination of this remarkable form and its functions, the authors provide a fascinating perspective on early modern drama, a perspective that enriches our knowledge of the plays' socio-cultural context and their mode of theatrical address and action.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prologues to Shakespeare's Theatre by Douglas Bruster,Robert Weimann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Elizabethan prologue

Text, actor, performance

Perhaps at no time, and nowhere, did prologues advance a more notable range of ambitions than in the plays of early modern England—the source of the prologues studied in this book. In fact, the myriad dimensions and issues implied by performance in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century play-houses and playing spaces require us to point out that, by ‘prologue’, we refer to a multifaceted phenomenon and term. Our use of ‘prologue’ acknowledges in particular three manifestations of the early modern prologue that, although closely intertwined, will reward serial examination in this chapter. These manifestations of ‘prologue’ include:

- the scripts for and textual traces of introductory performances that survive in printed playtexts and in other sources (sources which include mention of playhouse practices and expectations);

- the costumed actor who introduced plays in the theatres of Shakespeare’s day; and

- the performance of those theatrical introductions.

Thus ‘prologue’ operates as text, actor, and performance.

The overlap of these meanings will be familiar to those who study theatre history and those terms on which, in the words of Alan Dessen, early modern ‘dramatists, actors, and spectators “agreed to meet”’. 1 The complexity of the dramatic prologues of this era qualifies them in strong relation to what Dessen has elsewhere described as the period’s sometimes elusive ‘theatrical vocabulary’, such ‘preinterpretive materials’ as, for instance, ‘theatrical strategy and techniques taken for granted by Shakespeare, his player-colleagues, and his playgoers…building blocks (analogous to nouns, verbs, and prepositions), particularly those alien to our literary and theatrical ways of thinking today and hence likely to be blurred or filtered out by editors, readers, and theatrical professionals’. 2 However focused we may be on early modern modes of performance, dramatic prologues of that era remain largely ‘alien’ to our ways of thinking about theatrical representation. And, despite their density and rich descriptions, dramatic prologues are—with the notable exceptions, of course, of the well-known prologues to Romeo and Juliet (1596) and Henry V (1599)—often passed over by critics otherwise interested in social and theatrical history. 3

The reasons for such neglect are perhaps not far to seek. A number of widely held assumptions complicate any approach to prologues; adding to this problem is a certain critical reluctance to study conjunctures of dramatic form and social function. Together, these tendencies solidify an impression of the prologue as what an early twentieth-century commentator dubbed a ‘non-organic element’ of a dramatic text. 4 Prologues tend to be painted not only as awkward appendages, but as exemplars of a form archaic (from its classical and medieval heritage), artificial (from its highly formal nature, both as text and performance), redundant (from its apparent duplication of what the drama ‘itself’ is to present), uniform (from the common goals, language, and methods of many prologues), summary (from the prologue’s reputation for rehearsing the details of plot), and obsequious (from its tendency to seek favour of the audience). 5

Many of these characterizations are erroneous. Others have some truth in them. Early modern dramatic prologues, for instance, were indeed conventional and supplicatory. ‘Only we entreat you think’; ‘our begging tongues’; ‘we shall desire you of patience’: we hear these and other like phrases repeated frequently in prologues of this era. More valuable here than an apology for such features, however, is the simple point that it is precisely because dramatic prologues were asked to—among other things—introduce and request that they took up a position before and apparently ‘outside’ the world of the play. From this crucial position, prologues were able to function as interactive, liminal, boundary-breaking entities that negotiated charged thresholds between and among, variously, playwrights, actors, characters, audience members, playworlds, and the world outside the playhouse. The conventional nature of early modern prologues facilitated rather than diminished their ability to comment meaningfully on the complex relations of playing and the twin worlds implied by the resonant phrase theatrum mundi. The privileged and liminal position that prologues enjoyed—their place before the dramatic spectacle—produced one of their greatest attractions for those interested in how these plays were designed to appeal to, and mean for, their audiences. In the absence of extensive records of contemporary responses to specific plays, prologues offer cultural historicism some of the most significant characterizations of the early modern theatre. 6

Implying not only a ‘poetics’, but, in many cases, a poetics of theatre, even of culture, these prologues work to define the contours of theatrical representation in early modern England.

Prologue as text

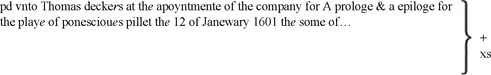

We have said that prologues can be seen as persons, performances, and texts. Because much of our information about the prologue-as-actor and prologue-as-performance comes from printed texts—especially the printed dramatic text—it will be helpful to ascertain what we know, most basically, about the prologue-as-text. We could start by pointing out that traces of several dramatic prologues from this era exist in potentia, prior to their composition as texts, as recorded in Philip Henslowe’s invaluable Diary. Three entries there note the entrepreneur’s payments for the composition of prologues. Each stipulates that a playwright provide both a prologue and an epilogue:

Here Henslowe enters the details of a payment of 10 shillings (‘xs’) for a prologue and epilogue to a play now lost, presumably titled Pontius Pilate (1597). Later Henslowe would record that 5 shillings had been lent ‘to paye unto mr mydelton for a prologe & A epeloge for the playe of bacon for the corte’, and, two weeks later, 5 shillings ‘to paye unto harey chettell for a prologe & a epyloge for the corte’. 7 As is so often the case, Henslowe’s Diary sketches in outline form the material basis of the early modern theatre; however varied—depending on the circumstances of the transaction—prologues (and epilogues) in these entries have a monetary value. Recognizing that prologues were commodities of a sort serves to remind us that the business of theatre during this period strongly correlated texts, performance practices, and the cultural worlds in and outside early modern plays. If prologues were never ‘merely’ texts, we nevertheless stand to see things about them that could otherwise escape notice by approaching them first in their textual form.

To begin with, we could ask how many plays had prologues? Thinking over titles of plays from this era, one can recall a number with remarkable prologues, but one can also think of many canonical plays without them: Kïng Lear (1605), The Revenger’s Tragedy (1606), The Tempest (1611), and The Changeling (1622), to name only a few. Were such plays, plays without prologues, the exception or the norm? Perhaps it would be most useful to ask, simply, How many dramatic prologues survive from the early modern era?

So far, the best answer to this question has been the figure advanced by Autrey Wiley, who offered, after counting works available to her: ‘From 1558 to 1642 the popularity of stage-orations increased, and about fortyeight per cent of the plays of this period had prologues and epilogues’. 8 Although Wiley notes that the popularity of dramatic prologues fluctuated during this period, we lack more specifics about such fluctuation. How popular were prologues, and how much did their popularity vary over time? Posing this question prompts us to delimit our inquiry to a particular range of years. If we wish to examine a period that borders the rise of the commercial theatres in England and their closing, the years 1560 to 1639 offer a convenient area of focus. For these eight decades, the indispensable Index of Characters in Early Modern English Drama: Printed Plays, 1500–1660 lists some 671 surviving plays. 9 Of these 671 plays, according to the list of characters compiled by the Index, some 268 have a prologue (or, more accurately, a ‘prologue’ figure usually—but not invariably—before the play). For the period in question, then, figures provided by the Index suggest that something like 40 per cent of the surviving playtexts feature a prologue.

We should notice, though, that this number varies significantly over time: according to figures derived from the Index, a high of 64 per cent of surviving plays originally performed from 1580 to 1589 have prologues, in contrast with a low of 31 per cent of surviving plays performed from 1590 to 1599. Although the total number of plays involved in this calculation is not so large that we can make confident pronouncements, it seems no coincidence that the decade with an apparently low number of prologues also sponsored a number of remarks, in and out of plays, about the patent artificiality (and apparently unfashionable nature) of prologues.

By the time of Romeo and Juliet in 1596, for instance, in response to Romeo’s query about a ‘speech…spoke for our excuse’, Benvolio would declare:

The date is out of such prolixity:

We…ll have no Cupid hoodwink’d with a scarf,Bearing a Tartar’s painted bow of lath,

Scaring the ladies like a crow-keeper,

Nor no without-book prologue, faintly spoke

After the prompter, for our entrance;

But let them measure us by what they will…(1.4.1–9)

That two of these lines (‘Nor no without-book prologue…/…for our entrance’) exist only in the Quarto of 1597 (the so-called ‘bad’ quarto) may well be a part of what one editor has called this text’s unusually sustained engagement with ‘contemporary stage business’. 10

In any case, Benvolio’s opinion would be echoed by the Stagekeeper of The Return from Parnassus, Part One (1600), who interrupts a boy prologue and indicts the form for being old-fashioned:

Prologue: Gentle-

Stagekeeper: How, gentle say you, cringing parasite?That scraping leg, that dopping courtesy,

That fawning bow, those sycophant’s smooth terms

Gained our stage much favour, did they not?

Surely it made our poet a staid man,

Kept his proud neck from baser lambskin’s wear,

Had like to have made him senior sophister.

..................................................................

Sirrah be gone, you play no prologue here,

Call no rude hearer gentle, debonair.

We’ll spend no flattering on this carping crowd,

Nor with gold terms make each rude dullard proud.

A Christmas toy thou hast; carp till thy death,

Our muse’s praise depends not on thy breath.(Pro. 1–7, 14–19) 11

The Stagekeeper criticizes the prologue after, and because of, a single word: ‘Gentle’. His indictment of this prologue comes, that is, on the basis of a linguistic register (‘gentle, debonair’) that implies a ‘dopping courtesy’ as insincere as it is unctuous (to ‘dop’ is to stoop, as in a curtsey). It is a register, and a repertoire, apparently so familiar that even a single word sketches out the entire routine. To the Stagekeeper, the tradition of the formal prologue is a sycophantic one best discontinued.

We hear something like an opposite account of the prologue’s associations used by the ‘Prologus Laureatus’ to The Birth of Hercules (1604). He notes the old-fashioned nature of the form with some approval:

I am a Prologue, should I not tell you so

You would scarce know me; ’tis so long ago

Since Prologues were in use: men put behind

Now, that they were wont to put before.

Th’epilogue is in fashion; prologues no more.

But as an old City woman well

Becomes her white cap still: an old priest

His shaved crown: A cross, an old church door:So well befits a Prologue an old play… 12

In contrast to the sycophantic, Osric-like quality that the Stagekeeper of The Return from Parnassus, Part One ascribed to the prologue, this speaker from The Birth of Hercules— while admitting the prologue’s outdated feel—groups dramatic prologues in a homely, nostalgic place with white caps, shaved crowns, and crosses. Perhaps disagreeing on the cause of its obsolescence, each speaker notes that the prologue seems outdated in London at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Although such statements need to be examined in much more detailed context than can be afforded here, when considered alongside the figures for prologues in plays surviving from the 1590s they seem to confirm a decline in the popularity of dramatic prologues during the later sixteenth and early seventeenth century.

Following this apparent decline, the percentages recover: from 31 per cent in the 1590s, the number rises to around 37 per cent for the 1600s and 1610s, 33 per cent for the 1620s, and 46 per cent for plays surviving from the 1630s. Significantly, remarks printed in other plays coincide with these figures as well. By the end of the 1630s, for instance, we have Suckling mentioning, in his prologue to The Goblins (1638), a new vogue for witty prologues: ‘Wit in a prologue poets justly may/Style a new imposition on a play;’ and in the Dedication to his Unnatural Combat (printed in 1639, but written a decade earlier), Massinger informs the reader that ‘I present you with this old Tragedy, without Prologue, or Epilogue, it being composed in a time (and that too, peradventure, as knowing as this) when such by-ornaments were not advanced above the fabric of the whole work’. 13 Each of these quotations gives us a playwright of the 1630s commenting directly on positive expectations, on the part of contemporary audiences, concerning prologues. It seems no coincidence, then, that the 1630s also witnessed the first publication of prologues as prologues, in Thomas Heywood’s Pleasant Dialogues and Dramas (1637). Heywood’s collection was followed by a remarkable quarto of 1642— remarkable because it anticipated Restoration practice—that reproduced the prologue and epilogue (and illustration of an actor who appears to deliver these ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Prologues to Shakespeare's Theatre

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- A note on texts

- 1 The Elizabethan prologue: text, actor, performance

- 2 Prologue as threshold and usher

- 3 Authority and authorization in the pre-Shakespearean prologue

- 4 Frivolous jestures versus matter of worth: Christopher Marlowe

- 5 Kingly harp and iron pen in the playhouse: George Peele

- 6 From hodge-podge to scene individable: John Lyly

- 7 Henry V and the signs of power: William Shakespeare

- Afterword

- Notes

- Index