- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

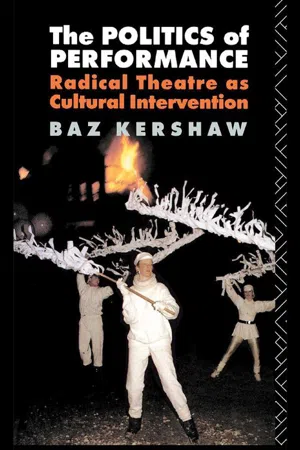

About this book

The Politics of Performance^ addresses fundamental questions about the social and political purposes of performance through an investigation into post-war alternative and community theatre. It proposes a theory of performace as ideological transaction, cultural intervention and community action, which is used to illuminate the potential social and political effects of radical performance practice. It raises issues about the nature of alternative theatre as a movement and the aesthetics of its styles of production, especially in relation to progressive counter-cultural formations. It analyses in detail the work of key practitioners in socially engaged theatre during four decades, setting each in the context of social, political and cultural history and focusing particularly on how they used that context to enhance the potential efficacy of their productions. The book is thus a detailed analysis of oppositional theatre as radical cultural practice in its various efforts to subvert the status quo. Its purpose is to raise the profile of these approaches to performance by proposing, and demonstrating how they may have had a significant impact on social and political history.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Performing ArtsPart I

Theory and issues

Alternative and community theatre as radical cultural intervention

Chapter 1

Performance, community, culture

I think the fringe has failed. Its failure was that of the whole dream of the ‘alternative culture’—the notion that within society as it exists you can grow another way of life…What happens is that the ‘alternative society’ becomes hermetically sealed, and surrounded. A ghetto-like mentality develops. It is surrounded, and, in the end, strangled to death.

(Brenton 1981:91–2)

if we think in terms of an expressive, rather than political revolution, then it is clear that the fringe, and the rest of the counter-culture, has not failed. It never had a coherent programme or a single identity, which is why single issues— feminism, ecology, community art—have become individual themes, rather than part of some overall strategy for change. But that does not detract from their significance.

(Hewison 1986:225)

The roots of a theory

Whatever judgement is passed on the social and political effects of British alternative and community theatre, it must be informed by the fact that the movement was integral to a massive cultural experiment. From this perspective the leading edge of the movement was not stylistic or organisational innovation (though both these were fundamental to its growth); rather, its impact resulted from a cultural ambition which was both extensive and profound. It was extensive because it aimed to alter radically the whole structure of British theatre. It was profound because it planned to effect a fundamental modification in the cultural life of the nation. Hence, the nature of its success or failure is not a parochial issue of interest only to students of theatre. In attempting to forge new tools for cultural production, alternative theatre ultimately hoped, in concert with other oppositional institutions and formations, to re-fashion society.

The chief purpose of this chapter is to construct a theory which will facilitate our investigations into alternative theatre’s potential for efficacy, both at the micro-level of individual performance events and at the macro-level of the movement as a whole. This requires that we address a number of basic questions about the relationships between performers and audiences, between performance and its immediate context, and between performances and their location in cultural formations. The answers will show how the nature of performance enables the members of an audience to arrive at collective ‘readings’ of performance ‘texts’, and how such reception by different audiences may impact upon the structure of the wider socio-political order. The focus will be on oppositional performances because the issue of efficacy is highlighted by such practices, but the argument should be relevant to all kinds of theatre.

My central assumption is that performance can be most usefully described as an ideological transaction between a company of performers and the community of their audience. Ideology is the source of the collective ability of performers and audience to make more or less common sense of the signs used in performance, the means by which the aims and intentions of theatre companies connect with the responses and interpretations of their audiences. Thus, ideology provides the framework within which companies encode and audiences decode the signifiers of performance. I view performance as a transaction because, evidently, communication in performance is not simply uni-directional, from actors to audience. The totally passive audience is a figment of the imagination, a practical impossibility; and, as any actor will tell you, the reactions of audiences influence the nature of a performance. It is not simply that the audience affects emotional tone or stylistic nuance: the spectator is engaged fundamentally in the active construction of meaning as a performance event proceeds. In this sense performance is ‘about’ the transaction of meaning, a continuous negotiation between stage and auditorium to establish the significance of the signs and conventions through which they interact.

In order to stress the function of theatre as a public arena for the collective exploration of ideological meaning, I will investigate it from three perspectives, drawn in relation to the concepts of performance, community and culture. I will argue that every aspect of a theatrical event may need to be scrutinised in order to determine the full range of potential ideological readings that it makes available to audiences in different contexts. The notion of ‘performance’ encompasses all elements of theatre, thus providing an essential starting point for theorising about theatre’s ideological functions. Similarly, the concept of ‘community’ is indispensable in understanding how the constitutions of different audiences might affect the ideological impact of particular performances, and how that impact might transfer (or not) from one audience to another. Lastly, theatre is a form of cultural production, and so the idea of ‘culture’ is a crucial component in any account of how performance might contribute to the wider social and political history.

Viewed from these perspectives, British alternative and community theatre between 1960 and 1990 provides an exceptionally rich field of investigation, for three main reasons. Alternative theatre was created (initially, at least) outside established theatre buildings. Hence, every aspect of performance had to be constructed in contexts which were largely foreign to theatre, thus making it easier to perceive the ideological nature of particular projects. Next, the audiences for alternative theatre did not come ready-made. They, too, had to be constructed, to become part of the different constituencies which alternative theatre chose to address, thus providing another way of highlighting the ideological nature of the movement’s overall project. Finally, alternative theatre grew out of and augmented the major oppositional cultural formations of the period. Particular performances were aligned with widespread subversive cultural, social and political activity, with the result that they were part of the most fundamental ideological dialectics of the past three decades.

This is particularly the case because, besides being generally oppositional, many individual companies and, to a large extent, the movement as a whole, sought to be popular. As well as celebrating subversive values, alternative theatre aimed to promulgate them to a widening span of social groupings. Hence, the movement continually searched out new contexts for performance in a dilating spectrum of communities. And often—particularly in the practices of community theatre—alternative groups aimed to promote radical socio-political ideologies in relatively conservative contexts. Thus, complex theatrical methods had to be devised in order to circumvent outright rejection. Inevitably, the whole panoply of performance came into play as part of the ideological negotiation, and all aspects of theatre were subject to cardinal experiment so that its appeal to the ‘community’ might effect cultural—and socio-political—change. In an important sense, then, we are dealing with a rare attempt to evolve an oppositional popular culture.

The nature and force of such a project prompt my fundamental interest in the potential efficacy of performance. So I am concerned now to see in what ways Brecht’s dictum that ‘it is not enough to understand the world, it is necessary to change it’ might be exemplified in both its aspects by British community and alternative theatre, at both the micro- and macro-levels of performance. Thus, whilst it is obvious that alternative theatre did not bring about a political revolution, it is by no means certain that it failed to achieve other types of general effect. As Robert Hewison argues, the possibility that it did contribute significantly to the promotion of egalitarian, libertarian and emancipatory ideologies, and thus to some of the more progressive socio-political developments of the last three decades, cannot be justifiably dismissed.

Ideology and performance

Ideology has been described as a kind of cement which binds together the different components of the social order. It has also been likened to plaster, covering up the cracks and contradictions in society (K.T.Thompson 1986:30). Whatever metaphor is preferred, though, the notion of shared beliefs is fundamental to most definitions of the concept. To put it at its simplest: ideology is any system of more or less coherent values which enables people to live together in groups, communities and societies. Thus, to the extent that performance deals in the values of its particular society, it is dealing with ideology. But in practice such dealing is far more complicated than this over-simple formulation suggests.

The concept of ideology has generated a minefield of interpretations regarding the ways it may relate to culture and society. The critical debates have been long and complex, as even the briefest glimpse of their major themes will show (J.B. Thompson 1990; Eagleton 1991). Marx used the term in a number of ways, but most influentially to refer to the ideas which express the interests of the dominant class of society. Durkheim broached the idea that for any society there may be a single social order which encompasses class differences, and thus a unitary ideology that can represent it. Recent Marxist theorists, following the lead of Althusser and Gramsci, generally argue that there is such an order, that it is run by a ruling class, and that it is largely the function of cultural production to reinforce the structures of power by promulgating (in many diverse and complex ways) a dominant ideology which operates in the interests of such ruling classes. Subordinate social groups accept this ideology through a process of hegemony. This concept indicates the predominance of a form of consciousness (or set of beliefs) which serves the interests of an exclusive social group, the ‘ruling class’. The majority in society, however, unconsciously collude in their own subordination because hegemony reinforces the dominant form of consciousness by making it seem ‘natural’ or ‘common sense’. Thus, hegemony works to ensure that dominant ideologies remain generally unchallenged. The ruling groups maintain their power and their control over the social system because the majority accept their predominance as the norm (Althusser 1971; Gramsci 1971:12–13).

In complete contrast to this position, the writings of structuralist and post-structuralist theorists, such as Foucault, Derrida and Baudrillard, tend to resist the idea of ideology in a world in which, from their perspective, language has become dissociated from its object, the sign from what it signifies. For these thinkers, any notion of a stable system of meaning is anathema, and so ideological concepts, such as ‘the self’, imply a ‘false transcendance’ (Sturrock 1979:15).

Between the post-structuralists and the neo-Marxists we can locate post-modernist theorists and cultural critics, such as Jencks and Collins. These argue for a pluralistic and de-centred competition of cultures and ideologies, within a society which has a multiplicity of orders in constant conflict with each other, thus precluding the possibility of a dominant ideology (Collins 1989; Jencks 1986). Again, the debates surrounding the idea of post-modernity—in what does it consist; in what ways does it affect society; etc.—have been complex and sometimes bitter. However, for the argument here I will adopt the version advanced by Fredric Jameson, who states:

I believe that the emergence of postmodernism is closely related to the emergence of [the] moment of late, consumer or multinational capitalism. I believe also that its formal features in many ways express the logic of that particular social system.

(Foster 1985:125)

Jameson’s argument raises the issue of whether or not a socially critical or effectively oppositional art can be created within the ‘postmodern condition’. Viewed from this perspective, the question of the potential efficacy of performance—and the nature of alternative theatre history—takes on an increasingly acute and urgent resonance as post-modernism inflects ever-widening social and cultural discourses.

Hence, the neo-Marxist position, vis-à-vis ideology, in part informs my argument. The evidence for at least a set of dominant ideologies, if not a single ideology, is much too great to be ignored. For example, one does not need to be a feminist to see that most aspects of Western society are organised patriarchally, or a homosexual to see that heterosexuality provides the dominant values which regulate sexual relations. The question of whether or not such dominant ideologies add up to a singularity—a dominant ideology—is beyond the scope of this study, though I will use the phrase ‘status quo’ to suggest that those ideologies tend to be mutually reinforcing. However, it is obvious that British society, in common with other ‘developed’ societies, is far too complex to permit a monolithic hegemonic control of every aspect of its culture. Thus the conflictual version of ideology presented by the post-modernists will also in part inflect my argument, since the dominant ideologies of Western societies—and their ruling groups— are frequently challenged by alternatives. Within or alongside the dominant ideologies other, oppositional, ideologies may struggle for cultural space and may sometimes even modify the dominant ideologies to a significant degree.

Cultural institutions and products are clearly central to the maintenance of dominant ideologies, and are frequently the locus for ideological struggle in society. In particular, theatre and performance are major arenas for the reinforcement and/or the uncovering of hegemony. British alternative theatre generally pursued the latter course. Therefore, it is my contention that, as a result of its nature and scale, the movement offered a significant challenge to the status quo, and may even have contributed to the modification of dominant ideologies in the 1970s and 1980s. This general efficacy became possible because performance was especially well suited to the styles of celebratory protest and cultural interventionism favoured by the new oppositional cultural formations which emerged between 1965 and 1990. As the companies of the alternative theatre movement were usually aligned with these formations they had, in one way or another, ideological designs on their audiences. And whether they aimed to celebrate or to protest against the ideologies of their different audiences, their over-riding purpose was to achieve ideological efficacy.

Performance and efficacy

To have any hope of changing its audience a performance must somehow connect with that audience’s ideology or ideologies. However, the longer-term effects—ideological or otherwise—that a performance actually might have on its audience, and their community or communities, are notoriously difficult to determine. This is ironic, given that we usually have little or no difficulty in observing, and even sometimes accurately describing, the immediate responses a performance provokes. It is doubly ironic in view of the well-documented power of performance to cause riots on occasion, and in view of the long history of censorship that theatre has suffered. If performance is powerless to affect the sociopolitical future, why then has it been taken so seriously by the successive powers that be? Despite this circumstantial evidence there has often been a widespread nervousness among theatre historians and critics about making claims for the efficacy of performance.

Nonetheless, the ghost of Aristotelian catharsis has haunted generations of writers on theatre. The most serious theorists of theatre, ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: In Quest of Performance Efficacy

- Part I: Theory and Issues: Alternative and Community Theatre As Radical Cultural Intervention

- Part II: A History of Alternative and Community Theatre

- Conclusions: On the Brink of Performance Efficacy

- Glossary

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Politics of Performance by Baz Kershaw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.