eBook - ePub

Foreign Direct Investment and Governments

Catalysts for economic restructuring

- 472 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Foreign Direct Investment and Governments

Catalysts for economic restructuring

About this book

This new paperback edition of Foreign Direct Investment and Governments examines the dynamic relationship between foreign direct investment, governments and economic development. The book includes:

* an investigation of the catalytic role played by the governments and multinationals in determining national advantages

* eleven in-depth national studies of the UK, USA, Japan, New Zealand, India, Mexico, Spain, Sweden, China, Indonesia and Taiwan

* analysis of all aspects of the investment development path

Foreign Direct Investment and Governments is an excellent source book for students of international business.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

The investment development path revisited

Some emerging issues

John H.Dunning and Rajneesh Narula

PART 1:

THE THEORY

The nature of the investment development path

The notion that the outward and inward direct investment position of a country is systematically related to its economic development, relative to the rest of the world, was first put forward by John Dunning in 1979, at a conference on 'Multinational Enterprises from Developing Countries' which took place at the East-West Center at Honolulu.1

Since then the concept of the investment development path (IDP)2 has been revised and extended in several papers and books (Dunning 1981, 1986, 1988a, 1993; Narula 1993, 1995; Dunning and Narula 1994). The following paragraphs summarize the state of thinking—prior to this volume—on the nature and characteristics of the IDP.

The IDP suggests that countries tend to go through five main stages of development and that these stages can be usefully classified according to the propensity of those countries to be outward and/or inward direct investors. In turn, this propensity will rest on the extent and pattern of the competitive or ownership specific (O) advantages of the indigenous firms of the countries concerned, relative to those of firms of other countries; the competitiveness of the location-bound resources and capabilities of that country, relative to those of other countries (the L specific advantages of that country); and the extent to which indigenous and foreign firms choose to utilize their O specific advantages jointly with the location-bound endowments of home or foreign countries through internalizing the cross-border market for these advantages,3 rather than by some other organizational route (i.e. their perceived I advantages).

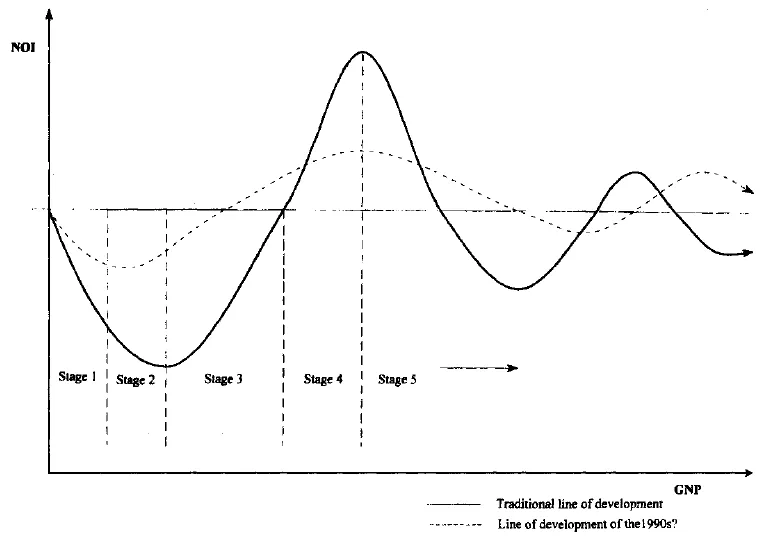

Figure 1.1 The pattern of the investment development path

Note: Not drawn to scale—for illustrative purposes only

A diagrammatic representation of the IDP, which relates the net outward investment (NOI) position of countries (i.e. the gross outward direct investment stock less the gross inward direct investment stock)—as a continuous line—is presented in Figure 1.1. We shall briefly summarize the main features of these stages, but pay particular attention to Stage 5, which we did not consider in our earlier writings.

Stage 1

During the first stage of the IDP path, the L specific advantages of a country are presumed to be insufficient to attract inward direct investment, with the exception of those arising from its possession of natural assets. Its deficiency in location-bound created assets4 may reflect limited domestic markets—demand levels are minimal because of the low per capita income—inappropriate economic systems or government policies; inadequate infrastructure such as transportation and communication facilities; and, perhaps most important of all, a poorly educated, trained or motivated labour force. At this stage of the IDP, there is likely to be very little outward direct investment. Ceteris paribus, foreign firms will prefer to export to and import from this market, or conclude cooperative non-equity arrangements with indigenous firms. This is because the O specific advantages of domestic firms are few and far between, as there is little or no indigenous technology accumulation and hence few created assets. Those that exist will be in labour-intensive manufacturing and the primary product sector (such as mining and agriculture), and may be government influenced through infant industry protection such as import controls.

Government intervention during Stage 1 will normally take two forms. First it may be the main means of providing basic infrastructure, and the upgrading of human capital via education and training. Governments will attempt to reduce some of the endemic market failure holding back development. Second, they engage in a variety of economic and social policies, which, for good or bad, will affect the structure of markets. Import protection, domestic content policies and export subsidies are examples of such intervention at this stage of development. At this stage, however, there is likely to be only limited government involvement in the upgrading of the country’s created assets, e.g. innovatory capacity and human resources.

Stage 2

In Stage 2, inward direct investment starts to rise, while outward investment remains low or negligible. Domestic markets may have grown either in size or in purchasing power, making some local production by foreign firms a viable proposition. Initially this is likely to take the form of import substituting manufacturing investment—based upon their possession of intangible assets, e.g. technology, trademarks, managerial skills, etc. Frequently such inbound foreign direct investment (FDI) is stimulated by host governments imposing tariff and non-tariff barriers. In the case of export-oriented industries (at this stage of development, such inward direct investment will still be in natural resources and primary commodities with some forward vertical integration into labour-intensive low technology and light manufactures) the extent to which the host country is able to offer the necessary infrastructure (transportation, communications facilities and supplies of skilled and unskilled labour) will be a decisive factor. In short, a country must possess some desirable L characteristics to attract inward direct investment, although the extent to which foreign firms are able to exploit these will depend on its development strategy and the extent to which it prefers to develop technological capabilities of domestic firms.

The O advantages of domestic firms will have increased from the previous stage, wherever national government policies have generated a virtuous circle of created asset accumulation. These O advantages will exist due to the development of support industries clustered around primary industries, and production will move towards semi-skilled and moderately knowledge-intensive consumer goods. Outward direct investment emerges at this stage. This may be either of a market seeking or trade-related type in adjacent territories, or of a strategic asset seeking type in developed countries. The former will be characteristically undertaken in countries that are either lower in their IDP than the home country, or, when the acquisition of created assets is the prime motive, these are likely to be directed towards countries higher up in the path.

The extent to which outward direct investment is undertaken will be influenced by the home country government-induced ‘push’ factors such as subsidies for exports, and technology development or acquisition (which influence the I advantages of domestic firms), as well as the changing (non-government-induced) L advantages such as relative production costs. However, the rate of outward direct investment growth is likely to be insufficient to offset the rising rate of growth of inward direct investment. As a consequence, during the second stage of development, countries will increase their net inward investment (i.e. their NOI position will worsen), although towards the latter part of the second stage, the growth rates of outward direct investment and inward direct investment will begin to converge.

Stage 3

Countries in Stage 3 are marked by a gradual decrease in the rate of growth of inward direct investment, and an increase in the rate of growth of outward direct investment that results in increasing NOI. The technological capabilities of the country are increasingly geared towards the production of standardized goods. With rising incomes, consumers begin to demand higher quality goods, fuelled in part by the growing competitiveness among the supplying firms. Comparative advantages in labour-intensive activities will deteriorate, domestic wages will rise, and outward direct investment will be directed more to countries at lower stages in their IDP. The original O advantages of foreign firms also begin to be eroded, as domestic firms acquire their own competitive advantages and compete with them in the same sectors.

The initial O advantages of foreign firms will also begin to change, as the domestic firms compete directly with them in these sectors. This is supported by the growing stock of created assets of the host country due to increased expenditure on education, vocational training and innovatory activities. These will be replaced by new technological, managerial or marketing innovations in order to compete with domestic firms. These O advantages are likely to be based on the possession of intangible knowledge, and the public good nature of such assets will mean that foreign firms will increasingly prefer to exploit them through cross-border hierarchies. Growing L advantages such as an enlarged market and improved domestic innovatory capacity will make for economies of scale, and, with rising wage costs, will encourage more technology-intensive manufacturing as well as higher value added locally. The motives of inward direct investment will shift towards efficiency seeking production and away from import substituting production. In industries where domestic firms have a competitive advantage, there may be some inward direct investment directed towards strategic asset acquiring activities.

Domestic firms’ O advantages will have changed too, and will be based less on government-induced action. Partly due to the increase in their multinationality, the character of the O advantages of foreign firms will increasingly reflect their ability to manage and coordinate geographically dispersed assets. At this stage of development, their O advantages based on possession of proprietary assets will be similar to those of firms from developed countries in all except the most technology-intensive sectors. There will be increased outward direct investment directed to Stage 1 and 2 countries, both as market seeking investment and as export platforms, as prior domestic L advantages in resource-intensive production are eroded. Outward direct investment will also occur in Stage 3 and 4 countries, partly as a market seeking strategy, but also to acquire strategic assets to protect or upgrade the O advantages of the investing firms.

The role of government-induced O advantages is likely to be less significant in Stage 3, as those of FDI-induced O advantages take on more importance. Although the significance of location-bound created assets will rise relative to those of natural assets, govern ment policies will continue to be directed to reducing structural market imperfections in resource-intensive industries. Thus governments may attempt to attract inward direct investment in those sectors in which the comparative O advantages of enterprises are the weakest, but the comparative advantages of location-bound assets are the strongest. At the same time, they might seek to encourage their country’s own enterprises to invest abroad in those sectors in which the O advantages are the strongest, and the comparative L advantages are the weakest. Structural adjustment will be required if the country is to move to the next stage of development, with declining industries (such as labour-intensive ones) undertaking direct investment abroad.

Stage 4

Stage 4 is reached when a country’s outward direct investment stock exceeds or equals the inward investment stock from foreign-owned firms, and the rate of growth of outward FDI is still rising faster than that of inward FDI. At this stage, domestic firms can now not only effectively compete with foreign-owned firms in domestic sectors in which the home country has developed a competitive advantage, but they are able to penetrate foreign markets as well. Production processes and products will be state of the art, using capital-intensive production techniques as the cost of capital will be lower than that of labour. In other words, the L advantages will be based almost completely on created assets. Inward direct investment into Stage 4 countries is increasingly sequential and directed towards rationalized and asset seeking investment by firms from other Stage 4 countries. The O specific advantages of these firms tend to be more ‘transaction’ than ‘asset’ related (Dunning 1993), and to be derived from their multinationality per se. Some inward direct investment will originate from countries at lower stages of development, and is likely to be of a market seeking, trade-related and asset seeking nature.

Outward direct investment will continue to grow, as firms seek to maintain their competitive advantage by moving operations which are losing their competitiveness to offshore locations (in countries at lower stages), as well as responding to trade barriers installed by both countries at Stages 4 and 5, as well as countries at lower stages. Firms will have an increasing propensity to internalize the market for their O advantages by engaging in FDI rather than exports. Since the O advantages of countries at this stage are broadly similar, intra-industry production will become relatively more important, and generally follows prior growth in intra-industry trade. However, both intra-industry trade and production will tend to be increasingly conducted within multinational enterprises (MNEs).

The role of government is also likely to change in Stage 4. While continuing its supervisory and regulatory function, to reduce market imperfections and maintain competition, it will give more attention to the structural adjustment of its location-bound assets and technological capabilities, e.g. by fostering asset upgrading in infant industries (i.e. promoting a virtuous circle) and phasing out declining industries (i.e. promoting a vicious circle). Put another way, the role of government is now moving towards reducing transaction costs of economic activity and facilitating markets to operate efficiently. At this stage too, because of the increasing competition between countries with similar structures of resources and capabilities, governments begin taking a more strategic posture in their policy formation. Direct intervention is likely to be replaced by measures designed to aid the upgrading of domestic resources and capabilities, and to curb the market distorting behaviour of private economic agents.

Stage 5

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, in Stage 5, the NOI position of a country first falls and later fluctuates around the zero level. At the same time, both inward and outward FDI are likely to continue to increase. This is the scenario which advanced industrial nations are now approaching as the century draws to a close, and it possesses two key features. First, there is an increasing propensity for cross-border transactions to be conducted not through the market but internalized by and within MNEs. Second, as countries converge in the structure of their location-bound assets, their international direct investment positions are likely to become more evenly balanced. It has been suggested elsewhere (Dunning 1993) that these phenomena represent a natural and predictable progress of the internationalization of firms and economies. Thus the nature and scope of activity gradually shifts from arm’s length trade between nations producing very different goods and services (Hecksher-Ohlin trade) to trade within hierarchies (or cooperative ventures) between countries producing very similar products.

Unlike previous stages, Stage 5 of the IDP represents a situation in which no single country has an absolute hegemony of created assets. Moreover, the O advantages of MNEs will be less dependent on their country’s natural resources but more on their ability to acquire assets and on the ability of firms to organize their advantages efficiently and to exploit the gains of cross-border common governance. Another feature of Stage 5 is that as firms become globalized their nationalities become blurred. As MNEs bridge geographical and political divides and practise a policy of transnational integration, they no longer operate principally with the interests of their home nation in mind, as they trade, source and manufacture in various locations, exploiting created and natural assets wherever it is in their best interests to do so. Increasingly, MNEs, through their arbitraging functions, are behaving like mini-markets. However, the ownership and territorial boundaries of firms becomes obscured5 as they engage in an increasingly complex web of trans-border cooperative agreements.6

The tendency for income levels to converge among the Triad countries has been noted, among others, by Abramovitz (1986), Baumol (1986), Dowrick and Gemmell (1991), and Alam (1992). Indeed, during the 1970s and 1980s, Japan, the EC and EFTA countries have experienced a ‘catching up’ in their productivity and growth relative to the United States (the ‘lead’ country); while a range of the newly industrializing countries began to move from Stage 2 to Stage 3 in their IDP.

As a result of these developments, the economic structures of many industrial economies have become increasingly similar. Countries which were once the lead countries in Stage 4 now find themselves joined by others. This tends to reduce their NOI position and pushes them into Stage 5 of the IDP. At the same time, there has also been a ‘catching-up’ effect among MNEs since the 1970s. Firms that have had relatively low levels of international operations have been internationalizing at faster rates than their more geographically diversified counterparts. These two effects are not unrelated; firms have had to compensate for slowing economic ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: The investment development path revisited

- Chapter 2: The United Kingdom

- Chapter 3: The United States

- Chapter 4: Sweden

- Chapter 5: Japan

- Chapter 6: New Zealand

- Chapter 7: Spain

- Chapter 8: Mexico

- Chapter 9: Taiwan

- Chapter 10: Indonesia

- Chapter 11: India

- Chapter 12: China

- Chapter 13: The investment development path

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Foreign Direct Investment and Governments by John Dunning,Rajneesh Narula in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.