Chapter 3

The impacts of learning on well-being, mental health and effective coping

Cathie Hammond

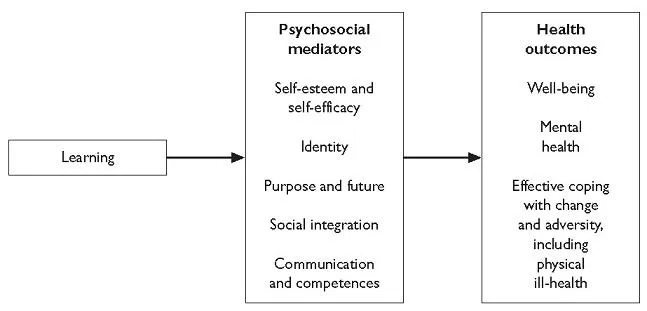

This chapter presents findings that link experiences of learning with health outcomes. Analyses of the fieldwork data suggest that learning can develop psychosocial qualities – namely self-esteem and self-efficacy, a sense of identity, purpose and future, communication and other competences, and social integration – which promote well-being, mental health and the ability to cope effectively with change and adversity, including ill-health. Respondents’ accounts also indicate which aspects of the learning experience may be important in relation to the promotion of positive health outcomes. A basic guideline for those wishing to maximise wider benefits is that the pedagogy, curriculum, student mix and institutional context should match the strengths, interests and needs of the learner.

Introduction: policy, practice and evidence

Reviews of the relevant evidence converge on the conclusion that education, as measured by years spent in education or highest qualification gained, leads to better health. These findings apply to measures of physiological, mental and psychological health. Although effects are on average positive, they vary depending on the health outcome and the learner’s gender, age and previous level of education (see, for example, Feinstein 2002a; Hammond 2002a; for reviews of the relevant studies, see Grossman and Kaestner 1997; Hartog and Oosterbeek 1998; Ross and Mirowsky 1999; Hammond 2000b).

I have previously suggested a typology of intermediate factors linking education and health as a first step towards understanding the processes through which education affects health (Hammond 2003). The factors described below can be categorised as economic, access to services, emotional resilience and social capital. In real life, these factors are related to one another as well as to education and health in complex ways. They are presented separately for conceptual simplicity.

Each additional year spent in education has positive returns in terms of income and socio-economic status in countries the world over (see, for example, Asplund and Pereira 1999 for a review of European evidence, and Johnes 1993 for a review covering developing as well as developed countries). Generally, health inequality means that individuals of higher socio-economic status are relatively healthy both physically and psychologically (Black et al. 1982; Acheson 1998). Education benefits individuals’ health by enabling them to move up the socio-economic ladder. This does not necessarily improve the situation of those who are left behind.

Effects of education upon health outcomes are mediated also by ability to access appropriate health and health-related services. The ‘inverse care law’ (Hart 1981) refers to the finding that areas characterised by deprivation and high levels of health needs also exhibit low take-up of health services. Educational success (or the lack of it) may affect individuals’ abilities to communicate effectively with health professionals and to understand and evaluate the health-related messages that they are given. These abilities benefit more educated individuals, but not the communities in which they live.

Emotional resilience refers to the dimension of individual difference that spans the ways we deal with adversity and stressful conditions and how they affect us (Garmezy 1971; Anthony 1974; Rutter 1990). Almost by definition, resilience contributes to better health: mental, psychological and physical. The relationship is perhaps most obvious in relation to depression since rates of depression are correlated with levels of self-esteem and self-efficacy, which are themselves central to resilience (e.g. Battle 1978; Burnette and Mui 1994; Turner and Turner 1999). However, in relation to depression, the directions of causality are unclear because loss of self-confidence and self-efficacy are symptoms as well as possible causes of depression. It is possible to imagine a vicious circle whereby individuals whose levels of resilience are low initially respond to adverse conditions by developing symptoms of depression, which themselves undermine their personal resilience to further adverse conditions. Education may play a part in breaking this cycle.

Resilience contributes to physical health, first through the promotion of positive health practices, and second through reducing chronic (as opposed to acute) levels of stress. Reliance upon nicotine, alcohol and other addictive substances, as well as certain patterns of eating, are sometimes responses to adversity and stressful conditions (Allison et al. 1999). Individuals who (through their education and learning) feel independent and confident, who are good at solving problems, who possess a sense of purpose and future, and who mix with peers who share these characteristics and live healthy lifestyles may respond to stressful conditions in ways which are less damaging to their health and possibly more effective in reducing levels of experienced stress in the longer term. Whereas short-term stress responses may be essential for survival, long-lasting stress exacts a cost that can promote both the onset of illness and its progression (see Wilkinson 1996: 179–181 on studies demonstrating that stress erodes physical health).

Social capital ‘refers to features of social organisation, such as trust, norms, and networks, that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating co-ordinated actions’ (Putnam 1993: 167). It is discussed in detail in Chapters 7 and 8; here I concentrate on the link between social capital and health. A review of the evidence suggests that the number of years spent in education is positively correlated with individual-level characteristics of social capital (Glaeser 1999) and that greater social capital leads to better health outcomes (Kawachi et al. 1997; Lomas 1998). Putnam (2000) suggests that social capital has a positive effect upon physical health because healthy behaviours are reinforced, chronic levels of stress are reduced, and access to medical services is improved. Within health promotion, there has been a ‘paradigm drift’ away from the provision of health-related information for individuals towards a community development perspective (Beeker et al. 1998), with an understanding of health-related behaviours as being shaped by collectively negotiated social identities (Stockdale 1995). Health promotion initiatives in Britain now emphasise whole community approaches to tackling health inequalities. For example, Health Action Zones explicitly link health to regeneration, employment, housing, education and social cohesion.

The discussion above draws on numerous studies that investigate either the outcomes of education (on the one hand) or determinants of health (on the other) and provide a basis for the typology of intermediate factors. The findings presented in this chapter similarly concern the factors linking learning with health, but no piecing together is necessary as the data are biographical in nature. The fieldwork research involved in-depth interviews with 124 respondents, plus 12 group interviews with practitioners. Interviewing a large number of respondents does not in itself add much to a qualitative study of this kind, but interviewing respondents with a wide range of life experiences – especially learning experiences – does. We have been able to investigate complex processes that are not easily disentangled using quantitative approaches across a very wide range of learning experienced by individuals from a variety of social backgrounds and encompassing a diversity of life experiences.

Obtaining a full contextual understanding of respondents’ learning and life experiences was necessary in order to disentangle effects of learning from other factors that influence people’s lives throughout the life course. Whitty and colleagues refer to ‘the cumulative effects of low social class of origin, poor educational achievement, reduced employment prospects, [and] low levels of psychosocial well-being [upon] poor physical and mental health’ (Whitty et al. 1998: 642). Systematic analysis of case studies enabled us to investigate the ways in which economic, political and social structures constrain people’s lives and limit or maximise the effects of learning. The biographical nature of the interviews also meant that both immediate and longer-term outcomes of learning could be investigated.

The design of the research was based on an understanding of health as encompassing not only physiological states but also mental and psychological ones. The interest was in both positive health and ill-health. Reflecting the typology of mediating factors outlined above, I assume that health may be influenced by a combination of social and psychological factors, as well as biological ones (Nettleton 1995; Crossley 2000).

Findings concerning mediators that link learning to health are summarised in Figure 3.1. The health effects of learning described by respondents fell into three categories: subjective well-being (SWB); effective coping, including coping with physical ill-health; and protection and recovery from mental health difficulties. In Chapter 2, we suggested that learning both sustains and transforms lives. Here we exemplify this more general finding: effects of learning that protect mental health are sustaining, and learning that leads to recovery of mental health is transforming. The processes involved encompass the maintenance and development of SWB and effective coping.

SWB refers to ‘how people evaluate their lives, and includes variables such as life satisfaction and marital satisfaction, lack of depression and anxiety, and positive moods and emotions’ (Diener et al. 1997). There is debate as to whether SWB is set at an early age, such that changes in income, health, family status and so on affect levels of SWB during adulthood for short periods only (e.g. Costa et al. 1987). Based on secondary analysis of a national US longitudinal survey (the General Social Survey), Easterlin (2003) presents a convincing argument that SWB is affected for periods of ten years or more by changes in health and family status, but not by changes in income. Although our respondents described educational impacts on well-being, it is not clear from their accounts to what extent education per se had long-lasting effects. However, learning effects on well-being interacted with other impacts of learning and led to changes in life circumstances, which appeared to have cumulative and lasting impacts on well-being.

Effective coping is a consequence of emotional resilience, described above as the ways in which we deal with adversity and stressful conditions. Lazarus and

Figure 3.1 Mediators between learning and health outcomes.

Folkman (1984) suggest that coping strategies that are effective in one context may be ineffective in another, which implies that learning may lead to effective coping in some but not all areas of a learner’s life. Howard et al. (1999) reviewed the literature concerning effective coping amongst children and concluded that the internal assets that consistently describe the resilient child are autonomy, a sense of purpose and future, problem-solving skills, and social competence. These internal assets match the psychosocial outcomes of learning described by respondents.

Thematic analysis of the case study evidence revealed five groups of psychosocial outcomes of learning that led to these health outcomes. They are closely related to the groupings of intermediate factors presented at the beginning of this section. Economic factors did not emerge strongly as mediators between education and health, probably because respondents were not encouraged to talk about them. Nevertheless, respondents’ accounts demonstrate the ways in which economic conditions shaped the impacts of education.

The following sections present evidence relating to the five groups of psychosocial resources that emerged as intermediate factors linking learning to health outcomes: self-esteem and self-efficacy; identity; purpose and future; communication and competences; and social integration. The final section discusses conclusions.

Self-esteem and self-efficacy

Self-esteem and self-efficacy are related but distinct constructs, and the literature on each is substantial. They are dynamic personal attributes that are both experienced internally and expressed through behaviour, what Mruk (1999) refers to as aspects of one’s ‘lived status’. Learners’ accounts exemplify changes in ‘lived status’ because they describe changes in self-esteem and self-efficacy in terms of both feeling and behaving differently.

Increased self-esteem is probably the most universal and widely documented ‘soft’ outcome of learning, and our findings bear this out. Every practitioner group and many individual respondents talked about self-esteem as an outcome of learning that was of central importance to them. Self-esteem refers here to ‘a generalised feeling about oneself that is more or less positive’ (Emler 2001). It includes the conviction that one is competent, and that one’s competences are worthy (Rosenberg 1965; Branden 1969).

Self-esteem is built when convictions about competence match up to or exceed aspirations (James 1890). Doris had left school without qualifications and returned to learning in later life, where she acquired competence in literacy.

Before, I thought I couldn’t do it. I got the idea I couldn’t do it, but of course I could. It just showed me that it can be done [. . .] It boosts your confidence loads.

As aspirations were fulfilled through learning, respondents developed new ambitions, reflecting the interplay between self-esteem, aspirations and a sense of purpose and future. I return briefly to this interrelationship in the section below on purpose and future.

Increased self-esteem was experienced as specific to certain abilities, feeling better about oneself generally, and feeling better about oneself in relation to others – students, contemporaries and friends, members of the family, and others in a general sense. However, some respondents described negative experiences within the education system during which they had failed to learn and which had undermined their self-esteem in each of these areas. Naomi describes the la...