- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Here Sian Lewis considers the full range of female existence in classical Greece - childhood and old age, unfree and foreign status, and the ageless woman characteristic of Athenian red-figure painting.

Ceramics are an unparalleled resource for women's lives in ancient Greece, since they show a huge number of female types and activities. Yet it can be difficult to interpret the meanings of these images, especially when they seem to conflict with literary sources.

This much-needed study shows that it is vital to see the vases as archaeology as well as art, since context is the key to understanding which images can stand as evidence for the real lives of women, and which should be reassessed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Athenian Woman by Sian Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

BECOMING VISIBLE

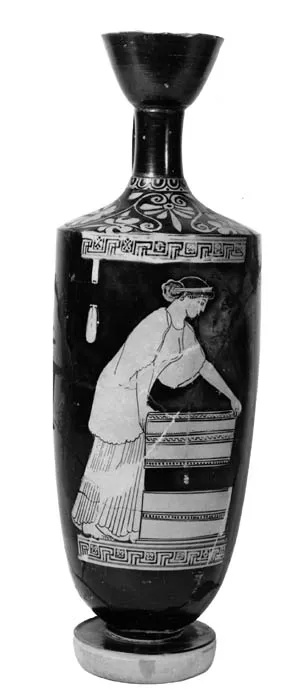

Many of the processes of a Greek woman’s life are mysterious to us. Comparative studies suggest that the central concerns of female life in the ancient Mediterranean were the family, including childbirth and child-rearing, events such as marriages and funerals, illness and death, and domestic chores.1 Yet in the case of classical Greece we know little of women’s early childhood, of female friendships, of training for married life, or of the experience of motherhood, probably the most significant emotional relationship in any woman’s life. In part this is due to the lack of literary sources written from a female perspective, but it is also a result of the agenda of Greek artists. A lekythos in Oxford attributed to the Providence Painter (fig. 1.1) illustrates very effectively the image of Greek women transmitted by pottery: an ageless and serene figure stands alone on a pot, lifting a chest in a vague domestic task; she is well-dressed, carefully depicted with clothes and jewellery as an object to be admired.2 Both image and activity are abstract, and the agelessness of the figure removes it from any consideration of the roles played by women throughout their lives – as daughters, sisters, wives, mothers and grandmothers. Can such an image offer any comment on the reality of female life at Athens?

Ceramic evidence, just like literature, is partial. It is possible to construct a cradle-to-grave story of female life using pots as illustrations, but only at the price of a very broad-brush use of evidence, taking scenes from disparate periods and regions to create an apparent whole.3 The lekythos in fig. 1.1 is a case in point: it appears to encapsulate the image of the ideal Athenian woman, yet it comes from Greek Sicily, from Gela, as do most of the lekythoi attributed to the Providence Painter (and indeed most red-figure lekythoi in absolute terms). The image was exported (possibly in a batch if the attributions to an individual artist are correct), and placed by an Italian Greek in a tomb. It was not painted for a specifically Athenian audience, nor was it a photographic representation of real life. A closer examination of the evidence is needed to determine the ways in which women became visible, both to Greek artists and to the citizens themselves. The woman of the Athenian potter appears in certain roles (as wife, as mourner, as worshipper), but is very infrequently shown in others (as young girl, as grandmother, as widow). Some aspects of female life such as ritual are richly illustrated; others, such as pregnancy, are never depicted. This arises at least in part from the use of the objects themselves; where pots were used in ceremonies or in practice, they tend to illustrate the occasion of their use, and hence evidence is plentiful, but where pots were not used, evidence is often lacking. This chapter will consider female life in the polis through the prism of ceramic iconography, to examine the ages of woman, and how they are (or are not) depicted on pottery.

From the cradle …

Let us begin at the beginning, with the birth of a girl. This immediately illustrates the nature of our evidence, since there are no scenes of childbirth on extant Greek pottery. The reason for this is complex, since childbirth was not a taboo subject: in other media, images of pregnancy, labour and birth are all found. On Athenian grave stelai, for instance, scenes of women in labour are frequent, relating either to mothers who died in childbirth, or to midwives as illustration of their profession. Although scenes of actual birth are rare, pregnancy is sometimes depicted.4 Birth is shown more fully on votive plaques and terracottas portraying pregnant women, or birth itself, which were dedicated in shrines across Greece, undoubtedly as offerings to pray (or give thanks) for successful delivery (fig. 1.2).5 Certainly birth is a topic more appropriate to some media than others, yet given the funerary use of so much pottery it is surprising that painters should avoid a theme so close to reality. From a comparison of the frequency of their depiction on pots, one would conclude that childbirth had a negligible importance, and that marriage was the most important event of female life. Pots illustrating weddings or preparation for marriage are extremely numerous, yet simply counting numbers of scenes does not expose the underlying meaning of the representations. Circumstances of survival play a part, since pots, especially loutrophoroi and lebetes gamikoi, were used in marriage ritual, and regularly carry images of their own function.6 The vessels used in marriage ceremonies were subsequently dedicated at the sanctuary of the Nymph on the Acropolis, and those who died unmarried often had them placed in their tombs, so they have tended to survive in the archaeological record. In contrast, pottery does not appear to have figured in rituals of birth: we are perhaps influenced by thoughts of our own customs in seeing birth as a moment for commemoration – in the ancient world, most babies would die, so their existence was less assured at the time of birth. But just because childbirth does not appear on pottery does not mean that it was not important to women: the birth of a child was a moment of enormous social significance. A marriage was completed not by the ceremony but by the birth of the first child, and the mother thereby completed the transition from parthenos to wife.7 Perhaps because of this, labour and birth formed, from the indications of both images and texts, an intensely private and female occasion. We have hints in Attic comedy that it was an occasion on which women gathered, with men excluded, and births were largely overseen by midwives.8 It was an occasion of great danger for the mother, and hence one in which the favour of the gods was essential. The arenas in which women celebrated successful birth were also private – by dedications of plaques, terracottas or personal belongings at the shrine of female deities – and were not rituals in which pottery played a part. As a personal and private event, childbirth never became a theme of pottery, which celebrated the public aspects of Greek life.

Figure 1.1 Attic red-figure lekythos, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum 1925.68, 470–460 BC. Photo courtesy The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Figure 1.2 Cypriot terracotta, Cyprus Museum, seventh century BC. After P. Dikaios, A Guide to the Cyprus Museum (Nicosia, Cyprus Government Printing Office, 1947), pl. 25.2.

That birth was considered a private female domain can be seen by comparing those scenes of birth which do appear on Greek pottery: mythological births. Scenes of the birth of gods and heroes are frequent: we see Athena and Dionysus emerging from Zeus’ head and thigh, Helen emerging from the egg, or Erichthonios being born from the soil of Attica itself.9 What these births have in common is of course their unnatural nature: the divine child emerges fully formed, either from the ground or from some part of a male deity. Only those births completely outside the regular pattern are depicted, the supernatural elements completely divorcing them from the pain and danger of normal birth. The only exception to this rule is Leto, mother of Artemis and Apollo: although representations of Leto actually giving birth appear only on non-Greek reliefs, pyxides found at Brauron depict her labour, or Leto with her infants.10 This is not coincidental: Artemis was the protector of women in labour, and Brauron the most important centre of her worship in Attica. The appearance of the scene illustrates the difference between male and female worlds; as we shall see, the creation of special shapes or scenes for women’s rituals is particularly linked with the rites of Brauron.

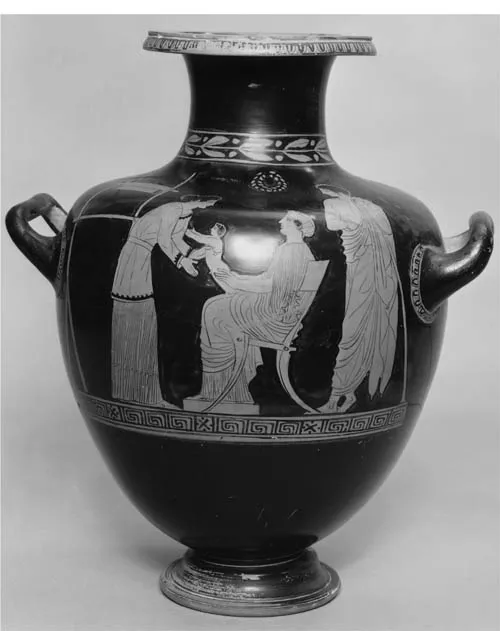

But if we see no female baby at birth, what about infancy? With childcare, as with other themes, reproducing a few well-known images can give a distorted view of ancient attitudes; it is easy to put together a set of images of mothers and children, both mythical and non-mythical, but context is of great importance. The representation of children on pottery was slow to develop, clearly because early artists found it difficult to depict babies and older children accurately. Babies are not shown in black-figure at all (one example on a pinax by Exekias demonstrates the struggle to define an iconography of the child), and children appear only in genre scenes such as mourning families, the departure of warriors, or with women at the fountain-house.11 In red-figure an iconography distinguishing infant, toddler and child gradually develops, and the range of scenes in which children are depicted becomes wider. Babies appear most often in the hands of a mother or nurse, as on the hydria in Harvard on which a nurse in a sleeved garment reaches out to take a baby from its mother (fig. 1.3), or another in London, on which a nurse hands a baby to its mother.12 The intention behind representations of children, however, is of a distinctive kind. The fact which needs emphasising is the funerary meaning of most of these images – rather than pictures of ‘everyday life’ they are pots illustrating death. The most obvious examples are those found on white-ground lekythoi, which were used in Attica and Euboia only, as funerary dedications, and on these the child of either sex is often shown in death: on a lekythos in private hands, a little girl stands at a tomb and holds out a doll (fig. 1.8); on another in Athens a child seated on the shoulders of a slave girl reaches out to his mother (fig. 1.4); a famous example in New York shows a male child gesturing to his mother as Charon’s boat approaches to take him to the Underworld.13 The lekythoi share the iconography of tomb monuments, and girls are depicted in death in this way, although boys are more commonly shown.

Figure 1.3 Attic red-figure hydria, Harvard University, Sackler Art Museum 1960.342, c.430 BC. Photo: Michael Nedzweski. Courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, Bequest of David M. Robinson.

It is from white-ground painting that some of the more moving examples of mother–child relationships come, such as the white-ground cup found in a tomb at Athens (fig. 0.3), which shows a mother holding out her hand to a young child seated in a high-chair. The expression of this kind of emotion was a private matter, rather than an aspect of Athenian life for public display and export, and the same is often true of child representations on red-figure pots: the Harvard hydria (fig. 1.3) is regularly used to illustrate female life, but it is one of several pots from the same source, a tomb in Vari (Attica); it forms a pair with another hydria, also in Harvard, which depicts three women preparing for a visit to the tomb.14 In the light of both context and decoration it seems reasonable to read the mother and child scene as funerary in meaning too, reflecting the iconography of both white-ground lekythoi and grave monuments.

This fact has implications for the representation of children. One factor which has received much discussion in recent years is the idea that all of the infants depicted on pottery are male, and that a canonical twisting pose is given to babies by painters, designed to present the male genitals to clear view. This practice is presumed to be in the service of an ideology: the production of a male heir was one of a wife’s main roles, and so the depiction of a woman with boy child is a scene of a job well done. To illustrate a girl child would be second best.15 This assumes that the role of the imagery is to endorse fundamental social at...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Becoming visible

- 2 Domestic labour

- 3 Working women

- 4 The women’s room

- 5 Women and men

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index