![]()

Part 1

Introduction

![]()

one

A Multidimensional View of Reading and Writing

The interest in the nature and consequences of literacy and its instruction has exploded during the last several decades. This explosion goes far beyond the perennial educational concerns about why Johnny (and Susie) can’t (or won’t) read. Disciplines as diverse as linguistics, cultural studies, and psychology have all come to view an understanding of the processes of reading and writing as critical to their fields. The emerging field of digital literacies is rapidly expanding our understanding of both the nature of text as well as text processing by drawing from work in media education and information and library sciences. Literacy has become multiliteracies, new literacies, or multimodal literacies.

Not surprisingly, there has been a tendency for each discipline to create literacy in its own image. Linguists emphasize the language or textual dimension of reading and writing. Cognitive psychologists explore the mental processes that are used to generate meaning through and from print. Socioculturalists view acts of literacy as expressions of group identity that signal power relationships. Developmentalists focus on the strategies and mediations employed, and the patterns displayed, in the learning of reading and writing.

Historically, these various disciplines have had a significant impact on how educators define, teach, and evaluate literacy in classroom settings. This has been particularly true for those teachers working in elementary schools, where literacy instruction is frequently privileged over all other subjects. During the 1960s, due largely to the seminal work of Noam Chomsky (1957), linguistics as a field of study rose to prominence. The discipline explicitly rejected the longstanding behavioristic paradigm for understanding the nature of language and documented the rule-governed and transformational nature of oral language production. Educationally, the rise of linguistics in the academic community resulted in the development and use of so-called linguistic readers—today called decodable texts—that emphasized the teaching and learning of letter–sound patterns, morphological features, and the syntactic relations represented in the language. Similarly, instructional strategies such as sentence combining were touted as avenues through which to improve student writing.

Following and building on the ground broken by the linguists was the ascendancy of cognitive psychologists, who began to document how readers and writers constructed meaning through written language. Emerging from this research was a fuller understanding of the active role of the individual in meaning making and of the critical differences in the strategies employed by proficient and less proficient readers and writers. Strategy instruction that helped students access and use appropriate background knowledge and to self-monitor their unfolding worlds of meaning as they interacted with print soon found its way into the curriculum. Reader response groups and process writing conferences also became commonplace in many classrooms.

Given the increasing acknowledgment of the linguistic and cultural diversity within the USA, various researchers are examining the sociocultural dimension of literacy. The ways in which literacy is defined and used as social practices by various communities (e.g., cultural, occupational, gender) are being documented. The nature of knowledge, its production, and its use as linked to literacy, ideology, and power are being uncovered. The educational impact of these explorations has been an increased sensitivity to the range of socially based experiences and meanings that students bring to the classroom. Additionally, educators have been challenged to ensure a more diverse representation of knowledges in the curriculum and more equitable access to these knowledges. Culturally responsive instruction and critical literacy are just two of the routes through which this sensitivity to diversity has been explored.

Accompanying and paralleling these trends were developmentalists’ explorations of how young children construct the linguistic and other sign systems, cognitive, and sociocultural dimensions of written language. These explorations have helped educators understand and appreciate the active, hypothesis-generating, testing, and modifying behaviors of the learners they teach. As a result of these new understandings, developmentally appropriate curricula and instructional mediation through scaffolding or apprenticeships have come to be seen as critical components in the teaching of literacy.

Of course, these historical trends are not as linear as they may appear—nor are they isolated by discipline. Obviously, various fields have investigated literacy at the same time. Also, each discipline has drawn from other disciplines when necessary. For example, cognitive psychologists utilized linguistic analyses of texts as they attempted to understand readers’ interactions with various types of written language. Similarly, socioculturalists have drawn on text processing research as they have explored how various cultural groups define and use literacy to mediate their interactions with the world. Consequently, we have psycholinguists, developmental linguists, social psychologists, and the like.

Most recently, this intersection among various disciplines can be seen in the work of those researchers exploring what have come to be known as academic literacies and multimodal literacies. Academic literacies reflect the ways in which language and thinking operate within such academic fields as the sciences, mathematics, and social sciences. Multimodal literacies explores how various sign systems—e.g., print, sound, color, images—are employed to construct meanings through texts. By necessity, researches in these areas draw from the fields of linguistics, semiotics, cognitive psychology, and sociocultural studies so as to better understand how literacy operates within different content areas and how meanings are constructed through different modalities. Not surprisingly, this research is reflected in the schools’ attempts to (1) address literacy in the content areas—especially as reflected in the common core standards—and (2) to expand literacy beyond the written word through the use of the internet, tablet computers, and other information communication technologies. However, even here, there is the danger of isolating or divorcing academic or multimodal literacies from other literacies. They become just one more isolated “subject” to teach.

If literacy education is to be effective, it is important that literacies be conceived as dynamic, interconnected, and multidimensional in nature. Becoming or being literate means learning to effectively, efficiently, and simultaneously control the linguistic and other sign systems, cognitive, sociocultural, and developmental dimensions of written language in a transactive fashion. In a very real sense, every act of real-world use of literacy—that is, literacy events—involves these four dimensions (Kucer, 1991, 1994, 2008b; Kucer & Silva, 2013; Kucer, Silva, & Delgado-Larocco, 1995).

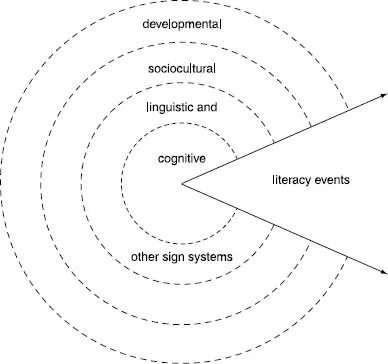

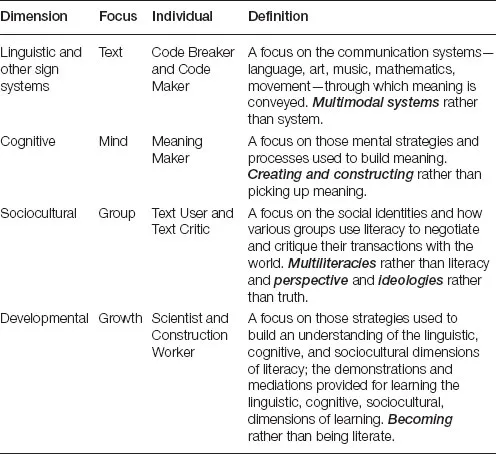

Figure 1.1 illustrates the relation among these four dimensions. Reflecting and extending the work of Gee (2012), Luke (1995, 1998), and the New London Group (1996), the linguistic dimension—and other sign systems—conceives of the reader and writer as “code breaker” and “code maker,” the cognitive as “meaning maker,” the sociocultural as “text user and text critic,” and the developmental dimension as “mediator, scientist, and construction worker.” Readers draw upon these four knowledge resources when engaged with any written language event.

Figure 1.1. Dimensions of literacy.

Adapted from Kucer S.B., Silva, C., & Delgado-Larocco, E. Curricular conversations: Themes in multilingual and monolingual classrooms (p. 59). York, ME: Stenhouse.

At the center of the literacy act is the cognitive dimension, the desire of the language user to explore, discover, construct, and share meaning. Even in those circumstances in which there is no intended “outside” audience, such as in the writing of a diary or the reading of a novel for pure enjoyment, there is an “inside” audience—the language users themselves. Regardless of the audience, the generation of meanings always involves the employment of various mental processes and strategies, such as predicting, revising, and monitoring. Interestingly, this cognitive dimension seems to transcend languages. Readers may employ many shared mental processes and strategies whether reading in their first or second language (Dressler & Kamil, 2006; Genesee, Geva, Dressler, & Kamil, 2006). Readers and writers as meaning makers create and construct rather than pick up or transfer meaning.

Surrounding the cognitive dimension is the linguistic and other sign systems dimension; the physical vehicle through which these meanings are expressed. Literacy depends on such language systems as graphophonemics, syntax, and semantics, and proficient language users have a well-developed understanding of how these systems operate. Not limited to language alone, readers and writers also make use of other sign systems for meaning making, such as color, sound, illustration, movement, etc. More than ever, literacy is a multimodal act consisting of various sign systems. The reader or writer must coordinate these transacting systems with the cognitive meanings being constructed. Readers and writers as code breakers and code makers employ many different multimodal systems rather than a single system to express meaning.

Literacy events, however, are more than individual acts of meaning making and language use. Literacy is a social act as well. Different groups use literacy in different ways and for different purposes. Therefore, the meaning and language that are built and used are always framed by the social identity (e.g., ethnic, cultural, gender) of the individual and the social context in which the language is being employed. Readers and writers as text users and text critics engage in multiliteracies rather than a single literacy and perspectives rather than truth.

Finally, encompassing the linguistic and other sign systems, cognitive, and sociocultural dimensions is the developmental. Each act of literacy reflects those aspects of literacy that the individual does and does not control in any given context. Potentially, development never ends, and individuals may encounter literacy events that involve using literacy in new and novel ways. These experiences offer demonstrations and opportunities for additional literacy learning that results in developmental advancements. Readers and writers act as scientists and construction workers as they build an ever evolving understanding of literacies. Becoming literate rather than being literate more accurately describes our ongoing relationship with written language (Leu, 2000). Table 1.1 summarizes these four dimensions of literacy.

Table 1.1. An overview of the dimensions of literacy

Crossing Borders: Disciplinary Perspectives Versus Literacy Dimensions

Each disciplinary perspective has contributed significantly to our understanding of literacy. Unfortunately, as previously noted, all too often these contributions have failed to consider, at least explicitly, the existence and impact of other perspectives. Taylor (2008) has observed that there have been few intellectual “border crossings” (p. x). Disciplinary perspectives frequently resulted in viewing reading and writing from a singular angle that obscured an understanding of how literacy operates in the real world. Each lens privileged a particular aspect of literacy for analysis and often ignored or downplayed others. Who was doing the looking and how the looking was accomplished determined what was ultimately seen.

Many cognitive psychologists, for example, in an attempt to understand the operation of perception in the reading process, have frequently examined the reader’s ability to identify letters and words in isolation. Individual letters or words are presented under timed conditions, and the responses of the readers are noted. Based on the responses and the time required for identification, particular understandings of the role and nature of perception in the reading process were developed. Not surprisingly, particular features of letters and words were found to be especially critical to effective and efficient perception. Such views have resulted in bottom-up theories of perception and the reading process.

If each act of literacy is conceived as involving various dimensions, however, it is critical that literacy as a multidimensional process not be confused with disciplinary perspectives. Not only must borders be crossed, they must be dismantled. In authentic situations—the reading or writing of real texts in the real world for real reasons—language is not stripped of its internal and external contexts. Rather, language is embedded in rich textual and situational environments that provide additional perceptual cues. An advertisement on a billboard, for example, will typically include letters and words that are framed by larger units of text, such as sentences. Although sentences are composed of letters and words, they also contain syntactic and semantic information.

In addition, advertisements often incorporate other communication or sign systems, such as illustrations, photographs, and numerals. The use of color and print size may also contribute to the message being conveyed. Finally, most readers understand the pragmatic nature of advertisements—that is, purchase this now; you need it! All of these textual and situational cues are sampled by readers as they generate meaning from print. Therefore, how the reader perceives isolated letters or words in tachistoscopic experiments may say little about how letters and words are perceived or utilized when they are embedded in broader situational and linguistic contexts (Cattell, 1885; Rumelhart, 1994). The use of such context-re...