- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pidgins and Creoles

About this book

The focus of this study is upon those pidgins and creoles which are English based and which have arisen since the fifteenth century. The book examines the widespread nature of the pidgin/creole phenomenon and evaluates the current definitions of the terms and the theories which have been advanced to account for their existence. The author considers the potential of pidgins and creoles as literary media and as vehicles for education. She looks at the sociological and psychological implications of using pidgins and creoles in the classroom and examines the position of American `Black English' and `London Jamaican' in the pidgin/creole continuum.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pidgins and Creoles by Professor Loreto Todd,Loreto Todd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

trɔki wan fait bɔt i sabi sei i han shɔt! (Tortoise wants to fight but he knows his arms are short), i.e. Know your limitations!

Pidgins and creoles are today to be found in every continent. References to their existence go back to the Middle Ages and it is likely that they have always arisen when people speaking mutually unintelligible languages have come into contact. Yet what are they? It is convenient to begin with the useful myth that we can give short, neat definitions of the terms ‘pidgin’ and ‘creole’, though it is worth stressing from the outset that the many-faceted nature of human languages is unlikely to be encapsulated in a few sentences. In a very real sense, the entire book is the definition, and the full nature of pidgins and creoles will emerge only gradually.

Pidgins and creoles have been given both popular and scholarly attention. Popularly, they are thought to be inferior, haphazard, broken, bastardized versions of older, longer established languages. In academic circles, especially in recent years, attempts have been made to remove the stigma so frequently attached to them, by pointing out that there is no such thing as a primitive or inferior language. Some languages, it is true, may be more fully adapted to a technologically advanced society but all languages are capable of being modified to suit changing conditions. Yet, while scholars have increasingly come to recognize the importance of pidgin and creole languages, there has been considerable debate, and disagreement, among them as to the precise meaning to be attached to the terms. The following definitions would, however, be widely accepted as a reasonable compromise.

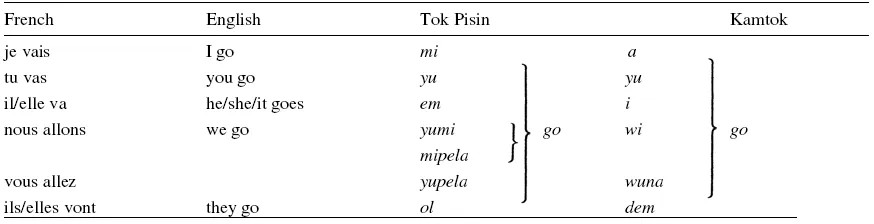

A pidgin is a marginal language which arises to fulfil certain restricted communication needs among people who have no common language. In the initial stages of contact the communication is often limited to transactions where a detailed exchange of ideas is not required and where a small vocabulary, drawn almost exclusively from one language, suffices. The syntactic structure of the pidgin is less complex and less flexible than the structures of the languages which were in contact, and though many pidgin features clearly reflect usages in the contact languages, others are unique to the pidgin. A comparison of contemporary pidgin Englishes, such as, for example, Tok Pisin (Talk Pidgin) in Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Kamtok (Cameroon Talk), the English-based pidgin of Cameroon, with English shows that the pidgins have discarded many of the inessential features of the standard variety, as two brief illustrations should clarify. All natural languages have some degree of redundancy. In many European languages, for example, plurality is marked in the article, the adjective and the noun, as well as, occasionally, by a numeral. In ‘les deux grands journaux’ there are, in the written form, four overt markers of plurality, three in the spoken form. English is, in this respect, less redundant than French, but in the comparable phrase ‘the two big newspapers’ plurality is marked by both the numeral and the noun ending. Tok Pisin (the pidgin English of PNG) and Cameroon pidgin are less redundant still, marking plurality by the numeral only, tupela bikpela pepa and di tu big pepa. The second example of discarding grammatical inessentials is illustrated in Table 1. English has less verbal inflection than French but both pidgins have an invariable verb form.

Table 1

A creole arises when a pidgin becomes the mother tongue of a speech community. The simple structure that characterized the pidgin is carried over into the creole but since a creole, as a mother tongue, must be capable of expressing the whole range of human experience, the lexicon is expanded and frequently a more elaborate syntactic system evolves.

A creole can develop from a pidgin in two ways. Speakers of a pidgin may be put in a position where they can no longer communicate by using their mother tongues. This happened on a large scale in the Caribbean during the course of the slave trade. Slaves from the same areas were deliberately separated to reduce the risk of plotting and so, often, the only language common to them was the variety of the European tongue they had acquired on the African coast, or on board ship or while working on plantations. Children born into this situation necessarily acquired the pidgin as a first language and thus a creole came into being. But a creole is not always the result of people being deprived of the opportunity to utilize their mother tongue. A pidgin can become so useful as a community lingua franca that it may be expanded and used even by people who share a mother tongue. Parents, for example, may use a pidgin so extensively throughout the day, in the market, at church, in offices and on public transport, that it becomes normal for them to use it also in the home. In this way children can acquire it as one of their first languages. This second type of creolization can probably occur only in multilingual areas where an auxiliary language is essential to progress. There is evidence that such creolization has taken place in and around Port Moresby and in other mixed communities in PNG (Wurm and Mühlhaüsler, 1985, p. 9), where Tok Pisin has for many a prestige status. Wolfers points out that ‘many New Guineans regard the learning of the pidgin as the most important turning point in their lives, when, for the first time, they are able to look for work outside their home areas. A knowledge of the language is still one sure way of gaining prestige as an educated man, and one capable of dealing with Europeans in some areas of the territory’ (1971, p. 415). A similar phenomenon is observable in Cameroon where, in the multilingual south-western area, pidgin has been the most useful lingua franca from at least as far back as 1884 when the German administration of the country began. So entrenched was pidgin English even then that the Germans had to issue a pidgin English phrase book to facilitate communication between their soldiers and the Cameroonians. In this area, as Rudin indicates, ‘there were so many dialects that the various tribes spoke and still do speak Pidgin English, to make themselves understood in their periodic market days’ (1938, p. 358). Today, pidgin English is even more widespread in the area and its very usefulness often makes it the language of choice even among speakers of the same mother tongue, and some children now use it as a first language.

In theory, the distinction between a pidgin and a creole is clear: a pidgin is no-one’s first language whereas a creole is. But this distinction is sociological rather than linguistic, as reference to specific cases shows. The so-called Cameroon pidgin, even where it is not a mother tongue, is not restricted to any region, class, occupation or semantic field. It is the vehicle for songs, witticisms, oral literature, liturgical writings and sermons, as well as being the most frequently heard language in the area. In all these functions it parallels Krio, the English creole of Sierra Leone, which is the mother tongue of over two hundred thousand speakers in and around Freetown. Since both languages are equally capable of serving all the linguistic requirements of their speakers it is hard to draw a linguistic line between them, though it can be pointed out that many Krio speakers use no other language whereas most speakers of Cameroon pidgin speak at least one Cameroonian vernacular as well.

An interesting point about creoles whose vocabularies derive from European languages is that their history is known. There is sufficient historical documentation to make it clear that they have developed from a contact pidgin which was subsequently adopted as a mother tongue. But if their history had not been known it is a matter of considerable debate whether they could, on linguistic evidence alone, be distinguished from other mother tongues. Such a consideration allows one to speculate that pidginization and creolization may have been much more prevalent in language change than linguists have hitherto acknowledged. It would be insightful to probe the changes Latin underwent in being transmuted into French. Did a pidgin Latin develop to facilitate communication between the Romans and the Gauls? Was it subsequently extended and creolized? Or was there already in the Roman army a simplified, common denominator Latin, from which dialectally divergent elements had been strained? Did a creolized Latin develop as a result of intermarriage? And was it continually influenced by the prestige of Latin, growing closer to it while still preserving features of the original pidgin? Such considerations cannot be fully explored in this book; but even posing the questions allows us to speculate that internationally respected languages like French may well have undergone similar processes to those which can be observed in the world’s present pidgins and creoles.

In this study the distinction between a pidgin and a creole will continue to be made according to whether or not the language is the mother tongue of a speech community, but in this case, a further subdivision of pidgins is required. Pidgins are auxiliary languages which can be characterized as either ‘restricted’ or ‘extended’. A restricted pidgin is one which arises as a result of marginal contact such as for minimal trading, which serves only this limited purpose and which tends to die out as soon as the contact which gave rise to it is withdrawn. A good example of this type of pidgin is what has been called Korean Bamboo English. This was a very restricted form of English which gained a limited currency between Koreans and Americans during the Korean war. It has by now almost disappeared, as has a similar variety which developed in Saigon during the Vietnam war. An extended pidgin is one which, although it may not become a mother tongue, proves vitally important in a multilingual area, and which, because of its usefulness, is extended and used beyond the original limited function which caused it to come into being. There is reason to believe that the many West African pidgins and creoles attained their present extended range of use because, having come into being as a result of contact between white and black, they were soon used and further developed in multilingual areas between black and black.

People in the western world tend to think in terms of standard, written languages and spoken forms closely related to these and strongly influenced by them. But in many parts of the world, even today, literacy is often rare and language standardization unknown. Such conditions were more common in the past, and in many regions travellers had to grope their way, linguistically speaking, and quickly establish some means of communicating. The communication exchanges often resulted in the simplifying of the language(s) concerned. When the contact was between closely related languages, processes of simplification and accommodation were at work, but a wholesale discarding of inflection was neither necessary nor helpful. An example may clarify this point. When the Vikings and Anglo-Saxons came into linguistic contact they shared a similar grammar and a considerable lexical stock. Communication common denominators were close at hand and many features common to Germanic languages could be maintained. Yet Anglo-Saxon did undergo a process of simplification as a result of this contact, a process which differed in degree rather than essence from the process of extreme simplification which English has undergone in certain contact situations where pidgins have arisen.

Far from being mere jargons or bastardized versions of standard languages, today’s pidgins and creoles may be attestations of what happens when, in societies not enslaved by the notion of literate standards, languages come into contact. They have resulted from the fusion of almost every possible combination of languages and occur in all inhabited areas of the world. In Europe Russenorsk, a pidgin now almost extinct, arose from the contact of two Indo-European languages, Russian and Norwegian, as a means of facilitating communication between Russian and Norwegian fishermen. In South America we find many creoles, among them Surinam’s Sranan, a creole which resulted from the contact of English and a variety of West African languages. In the Pacific, in PNG, Hiri Motu arose from the contact between speakers of Motu and other Papuan vernaculars. It has recently expanded its vocabulary by adopting words from Tok Pisin. Chinook Jargon is now almost entirely restricted to Canada but in the nineteenth century it was spoken from Oregon to Alaska. This pidgin is thought to have developed from the contact of French and English with Chinook and Nootka; but there is still controversy over its origin (see Hancock, 1972, p. 3). In Africa, in the Central African Republic, the pidgin Sango developed due to the contact of Ngbandi with other African languages. Along the coast of China, in Shanghai and to a lesser extent in Hong Kong, one finds relics of the once widespread China Coast Pidgin English which arose as a result of the contact between English and coastal Chinese. These six cases are only a sample of the variety of possible combinations but they give some indication of how widespread the pidgin/creole phenomenon is (see Map 1).

A final clarification may be useful in order to indicate the distinction between a pidgin variety of a language and a dialect. The pidgin/dialect dichotomy is one which requires attention because there are areas like Jamaica and Hawaii where the distinction is not easily drawn. It is true that in many cases dialectal differences can be explained without reference to historical contact with another language. In addition, the majority of dialects of English are mutually intelligible. Pidgin and creole varieties of English can, on the other hand, only be explained by reference to other languages and they are often mutually unintelligible, with each other and with standard international English. Again, an example can highlight these differences. Where standard English has ‘I was standing at the corner gossiping’, some dialect speakers in Leeds say ‘I were stood at t’ corner gossiping’, and a Cameroon pidgin speaker would say a bin tanap jɔ kɔna an a bin di kɔnggɔsa. One can see that those who produce the first two sentences are using the same lexical and syntactic material in that they are both using a form of the sentence I + past tense of BE + marked form of the verb STAND + prepositional noun phrase + gossiping, whereas they differ from the pidgin sentence in both vocabulary and syntax. One can only explain the occurrence of kɔnggɔsa by referring to the West African languages, including Twi, in which it means gossip.

Further examination of pidgins/creoles and dialects, however, indicates that the distinction is not always as clear as the above examples suggest. In Jamaica, where the creole has been exposed to the regular and increasing influence of the standard international variety of English, we find a whole spectrum of Englishes, referred to as the ‘post-creole continuum’ and ranging from deep creole through creole-influenced forms to a regional variety of the international standard. As well as the standard I didn’t get the ball, we can attest the following variations mi no get di ball, mi neva get di ball, mi din get di ball, a neva get di ball, a din get di ball. And, in Ireland, where the non-standard varieties of English are described as ‘dialects’ a similar spectrum exists, a spectrum showing different degrees of influence from Gaelic. Limiting oneself to syntactic difference we can range from the strongly influenced Would you see does he be at himself in the evenings? through a form, recognizable if still non-standard, Would you see is he in good form in the evenings? to the standard Could you check that he is all right in the evenings?

While acknowledging the inherent similarities in certain pidgin/creole and dialect situations, it may be remarked that the differences between Hiberno-English and standard English can all be explained by reference to one language, Gaelic, but the differences between any extended pidgin or creole and standard English are much less easily identified. And, leaving aside for the moment language-influenced dialects of English, it can be said that all dialects of English, whether regional or social, share a large number of phonological, lexical and syntactic features with the standard form and that there is no area where two abutting dialects are mutually unintelligible. In PNG, however, a pidgin English does exist side by side with a standard Australian English, and that the two are mutually unintelligible is clear from the following soap powder advertisement in Tok Pisin: ‘Olgeta harim gut! Dispela sop pauda, ol i kolim “Cold Power” i nambawan tru. Em i wasim na rausim tru ol kainkain pipia long ol klos bilong yu.’ (‘Everybody listen closely! This soap powder, called “Cold Power” is definitely the best. It washes and completely removes all kinds of stains from your clothes’) (Wantok, pes 5, Trinde, Ogas 18, 1971—One-Language/ Compatriot, page 5, Wednesday, August 18, 1971).

It will become increasingly clear that pidgins and creoles are not simply dialects of English whose differences from the international standard can be explained in terms of regional and temporal distance. Pidgin and creole Englishes have arisen in multilingual areas where speakers of English have come into contact with speakers of languages which are structurally very different, where English has been so influenced by the other languages that the grammar of the pidgin which emerges is not just a simplified grammar of English or a simplified version of the grammar of the other languages. It is not even a common denominator grammar of the contact languages. Rather, the grammars of creoles and extended pidgins are a restructuring of the grammars that interacted. A grapefruit has much in common with both oranges and lemons but its taste is uniquely its own. In the evolution of pidgins, and thus of creoles, new languages have come into being. This fact allows us to suggest an interesting distinction between a pidgin English and a variety like Hiberno-English. In creoles and extended pidgins we find not a reduced, or partial, or corrupt form of the grammar of English but a new system, related to the contact languages but possessing unique features. In the case of Hiberno-English, English has certainly been influenced by Gaelic, but there has been no drastic restructuring of its grammar, partly because the contact was between two languages only and partly because the pressure from standard British English has been uninterrupted and all-pervasive. One can therefore specify three main varieties of English apart from the international norm: ‘dialects’ where regional and/or social differences occur, ‘dialects’ where English has been influenced by another language, and pidgin and creole Englishes where the grammars of English and other languages have come into contact and been restructured into a new though related language.

In an introduction we have, of necessity, to skim the surface of the subject. In consequence, emphasis on certain points may temporarily force others out of focus. It has been suggested that the process of pidginization, that is the manoeuvres towards simplification which take place whenever and wherever people of linguistically different backgrounds are brought suddenly into contact, is not an unusual or exotic occurrence. The process, though usually short-lived, may be observed in markets frequented by foreigners, in tourist hotels, on guided tours; wherever, in fact, people who have elementary communication needs but possess only a vestigial grasp of each others’ languages, come into contact. But the creation of a pidgin and its elaboration into either an extended pidgin or a creole, while not uncommon, is much rarer than the actual process of pidginization itself. The emergence of such a language as a permanent form is not merely the result of people coming into contact and influencing each other; rather it is the birth of a new langua...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Maps

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Language and name

- Chapter 3: Theories of origin: pidgins

- Chapter 4: The process of development: from pidgin to creole

- Chapter 5: The scope of pidgins and creoles

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Appendix one

- Appendix two

- Appendix three

- Appendix four

- Bibliography