1 Introduction

The world economy after the war, 1945–50

EFFECTS OF THE WAR

The Second World War which came to an end in 1945 had caused more destruction, human as well as material, than any previous conflict. Europe had suffered most, together with Japan, but there was massive destruction also in China and south-eastern Asia, there had been much fighting which ravaged North Africa, and all maritime nations had sustained grievous losses at sea. The United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, among others, had devoted enormous resources to the war though they had been spared actual warfare on their territory, and, together with the colonial dependencies of the European powers, they mourned many killed and injured in the forces. Few areas of the globe outside Latin America were left unaffected.

In Europe alone, between 40 and 45 million people lost their lives: no exact count is possible, since many of those who died, especially among the more than 20 million victims in the Soviet Union, were civilians who perished in air raids, in labour camps or on the road, having been driven out of their homes. About 6 million Jews were killed in the Nazi death camps. Three million non-Jewish Poles and 1.6 million Yugoslavs also lost their lives. When the fighting ended, there were some 15 million ‘displaced persons’ awaiting repatriation. To these have to be added the missing births, and the millions of the injured.

China’s military losses included 1.3 million dead, while an additional 9 million civilians died in the war period and a further 4 million in the famine of 1945–6. Japan lost 2.5 million dead, and the human losses among other Asian countries, mostly civilian, may have numbered up to 5 million. American losses among the armed forces totalled 400,000 dead and 700,000 wounded, and other Allied non- European losses among fighting men and civilians added a further 2.5 million dead. The total may well have exceeded 60 million people who died as a result of the war.

The psychological costs of all these human disasters are incalculable, as are the traumatic effects of the nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the survivors. Not least, there was a residue of national hatred which poisoned many parts of the world for years to come.

Among material losses, damage to housing and other buildings loomed large. In the Soviet Union 17,000 towns and 70,000 villages were destroyed, while Germany lost 20 per cent of her housing stock and Britain 9 per cent in the bombing, as well as damage to many more. Capital was run down or wrecked all over Europe: factories had been bombed, railway tracks destroyed, bridges were down. Thus the Soviet Union had 65,000 km of railway track and 13,000 bridges destroyed. Of the 17,000 pre-war French locomotives, only 3,000 were serviceable. Despite much building, both the British and Japanese mercantile fleets were 4½ million gross tons down on prewar, Germany’s shipping was reduced from 4½ million to 700,00 gross tons, and Italy’s from 3.4 million to 700,000 gross tons. Many harbours were blocked and canals had been put out of action. Agriculture also suffered grievously: in Poland, for example, it was estimated that 60 per cent of farm livestock had been lost.

The destruction affected different parts of the world most unevenly. Worst hit were Germany, eastern Europe, large areas of China, and Japan, but there was much damage also in western Europe including Britain, in Italy and in Greece. In the areas most affected, the outlook seemed grim indeed. Factories needed fuel and raw materials to restart, but these could not be delivered because the means of transport were out of action, and these could not be repaired because the factories were not working. Agricultural output was down because so many of the men had been killed, as well as because of the lack of equipment and fertilizer, and as a result workers in towns were undernourished and less productive. The breakdown of normal economic relations was marked in some countries by the replacement of money by barter exchange, or the use of cigarettes as currency. Much labour had to be devoted just to clear the rubble and provide temporary housing. In many areas the economic problems seemed insoluble, and relief agencies, such as the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), had to devote much of their resources simply to ensure bare survival.

As the conflict of 1939–45 had fully engaged the economies of the industrialized belligerents especially in Europe and Japan, their-traditional role of supplying manufactures to the rest of the world had largely fallen into abeyance in the war years. The United States had still much surplus capacity and filled some of the gaps, particularly in Latin America, but other economies had to look to their own resources to meet their demand for manufactures, and there was a considerable indigenous growth of industry in such countries and regions as Australia, South Africa, South America and parts of Asia. Much of this industry would be vulnerable to competition from the advanced world, once peace conditions returned, but some survived as the basis for successful post-war industrialization.

The traditional exports of the non-European world, consisting of raw materials and food products, were also in high demand, which was possibly even strengthened in the early peace years, as in so many areas simply to have enough food for sheer survival had overriding priority. It was also the case that at the time it was more difficult to raise the productivity on farms than in factories. In fact, the output of most foodstuffs, apart from rice, which was not a major food grain in the western world, stagnated in the war years, while world population increased. World wheat production actually fell from 176 million tons in 1938 to 157 million tons in 1948. European grain and potato crops had in 1947 fallen to two-thirds of their pre-war level. The result was that the prices of ‘primary products’ rose faster than the prices of manufactured products, and the tendency was reinforced by the stockpiling of raw materials in the Korean war boom of 1951– 2. The relative prices between these two types of commodities, manufactures and primary products, known as the ‘terms of trade’, thus turned at least for a time in favour of countries exporting the latter, mainly food and raw materials, which mostly meant the poorer countries outside Europe.

The countries not directly occupied or damaged tended to be relative gainers from the changes produced by the war. This was above all true of the United States. As far as manufactures were concerned, the USA produced almost half the world’s total in 1946, compared with only 32 per cent in 1936–8, while containing only 6 per cent of world population. Her mercantile marine rose from 17 per cent of the world’s tonnage in 1939 to 53 per cent in 1947. Latin America, too, was a gainer: its share of world exports rose from 7–8 per cent in 1938 to 13–14 per cent in 1946, though much of that trade was among the region’s countries themselves. It was symbolic for the region’s progress that its energy consumption had risen by 82 per cent between 1939 and 1947. In Africa, the regions supplying important materials, such as the Belgian Congo, East Africa and South Africa, gained: the rest actually lost out. Europe, which had accounted for 47 per cent of world trade in 1938, had seen its share shrink to 41 per cent in 1948.

Yet recovery, at least among the industrialized belligerent nations, was remarkably rapid. There were many reasons for that resilience. For one thing, while much civilian production had been stopped in the war years, there was substantial new engineering, metalworking and chemical capacity created for armaments production, much of which could easily be converted to peacetime uses. Moreover, the infrastructure, such as roads, bridges or power lines, was in place, and, though badly damaged, had merely to be repaired. Above all, there were skilled and knowledgeable people, workers and technicians, used to industrial and social discipline, who could be mobilized fairly quickly to set the wheels going again. There was also a long tradition of saving and capital creation, of reasonably competent government and effective markets. Additionally, help came in the form of machines, raw materials and food from the undamaged countries such as the USA and Canada, some of it, as we shall see later, provided free or against long-term repayment.

MEASUREMENT OF NATIONAL INCOME

Thus by 1950 the available statistical information shows that most affected countries had reached income levels well above those of prewar, and others were rapidly approaching these. The composition of the goods and services they consumed might be different, but in total, what is known as the ‘Gross National Product’ (GNP) per head showed a clear advance over the 1930s. This concept of GNP will appear again later, and it will therefore be worthwhile to explain briefly what is meant by it, its usefulness and its dangers.

The idea behind the GNP is to add together all goods and services made available within the economy; if we divide that total by the number of people, we get GNP per head. Double counting has to be avoided: thus we do not count the output of steel and the output of cars into which it enters, but only the latter. If we deduct all goods and services which go into replacing capital worn out, on the grounds that this does not really represent anything available to people as consumers and is really a cost, we arrive at Net National Product (NNP). Armed with such figures, we can then proceed to compare the totals of goods and services available in different years for one country, or in different countries, provided we value everything at the same ‘constant’ prices. Thus we can see whether output and standards of living have been growing or declining, and how one country or region compares with another.

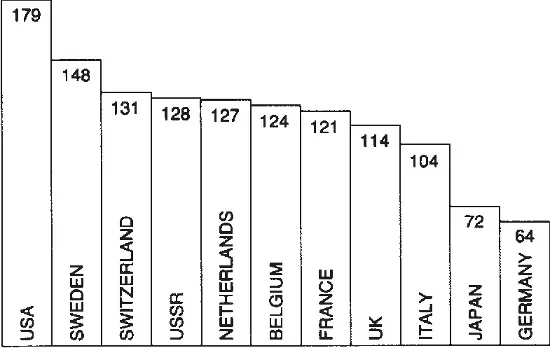

Figure 1.1 GNP at constant prices in 1950 in selected countries, 1938–100

Such calculations are not without their problems. Thus it is difficult for the statisticians to count the foodstuffs consumed on farms themselves which do not enter any markets; or, to cite another example, we do not count the work of housewives in the home. If they bake their own bread, their contribution is not counted; but if they buy from the baker, it does become part of the registered ‘national product’: this means that the figures will show an increase in output where none had occurred. These and other gaps affect low-income countries far more than richer nations, and GNP or NNP figures are therefore particularly suspect when comparisons are made between these two types of economies. Thus if we see GNP figures which show, say, American incomes to be fifty times higher than incomes in some parts of the Third World, such figures should not be taken as precise meaningful measurements, but merely as general indications. Among similar economies, however, the GNP and NNP measures are the best means available to compare relative production totals and rates of change.

Figure 1.1 shows that the United States which had worked at far below full employment in the 1930s and therefore started out with much spare capacity, had registered the most impressive growth. The neutrals in the war, Sweden and Switzerland, had also improved their position by wide margins. But even among the belligerents, the victors stood well above their pre-war levels. Among the Axis losers, Italy had recovered more successfully than Germany or Japan.

Table 1.1 GNP per head: some representative regions and countries, 1950 (in prices of US $ of 1974)

However, the really large differences were still those between different parts of the world. The position as it appeared in 1950, when the worst of the war damage had been made good in the west, is illustrated in Table 1.1.

Even if we bear in mind the remarks made above on the problems of assigning GNP figures to poor economies and take account of differences of climate, social structure and tradition, it is clear that the poverty of non-European countries was of a different order from the temporary problems of the European nations. The scourge of disease and the high death rates, the widespread hunger and the lack of amenities prevalent in many of those areas, were of a kind unimaginable to Europeans. Nevertheless, possibly because the plight of the non-Europeans was of long standing, while Europe had suffered a drastic deterioration, and possibly also because it had more political clout and believed that its ills could more easily be remedied, it was the latter which received the greater attention at the time.

THE ROLE OF THE USA IN THE WORLD ECONOMY

The Europeans, suffering what to them were unparalleled shortages of food, of fuel, raw materials and capital equipment in the immediate post-war years, saw the only possible source of supply to lie in the surplus stocks and the undamaged productive powers of North America—if only these could be afforded. But to pay for them required dollars: far more dollars than the rest of the world possessed or could get hold of.

In consequence, in the post-war years the economic outlook of the industrialized world came to be dominated by the so-called ‘dollar shortage’. At the time, it seemed to symbolize a fundamental and permanent shift, as a result of the war, in the distribution of the world’s economic weight, away from Europe and towards North America. It looked as though it would never be possible to catch up on the productivity of the USA, since that country not only had the richer natural resources, but also, being richer, could invest more capital year by year, and thus always keep ahead technologically. As it turned out, this fear was misplaced, and the dollar shortage was to be short-lived, but this remained hidden from contemporaries. We shall see below how it was overcome in due course, but even after the dollar had ceased to be scarce, the dominant role of the United States remained and was to become a permanent feature of the world economy for the next half-century and beyond.

POLITICAL CHANGES

Such economic hegemony as the USA enjoyed could not be divorced from political power. Unlike the period following the First World War, when the United States had similarly entered the fighting at a late stage, to make a decisive contribution to victory for the Allies, but had then withdrawn into isolationism, this time she determined to take her place as the leading political power. Backed by her overwhelming economic as well as military might, she became one of the two ‘superpowers’ in the second half of the twentieth century, the other being the Soviet Union. For that and other reasons, the history of the world economy in that period cannot in fact be separated from the political developments which formed the framework within which the world economy had to operate.

Three political changes which followed the end of the Second World War stand out in importance in this context. The first of these was the division of the industrialized world into two hostile camps: the western, ‘capitalist’ and largely democratic countries, led by the United States as the dominant power, and the eastern, ‘socialist’ countries, dominated by the Soviet Union. From being allies in the war, the two superpowers and their satellites or supporters eyed each other with increasing suspicion from 1947 onwards. The Soviet Union expanded westward, absorbing the three Baltic states and parts of Poland, Germany and Romania; she also used the power of the Red Army to help to install communist governments in a number of her eastern European neighbours. The United States, for her part, used her economic power to prevent countries in the rest of the world from following the same path, and surrounded the Soviet Union with a ring of threatening military bases. Each of them tied their allies to themselves by tight military alliances, NATO and the Warsaw Pact, respectively.

Though armed to the teeth with increasingly costly, sophisticated and lethal nuclear weapons and means of delivering them, they avoided going to war with each other directly, merely keeping going a state of hostility which became known as the ‘Cold War’. However, several proxy armed conflicts were fought, the most destructive of them being the Korean war (1950–3), the Vietnam conflict (1965–75) which involved the USA in a major way, and the Afghanistan war (1979–88) in which the USSR got embroiled. Additionally, there were numerous minor conflicts, including several bitter civil wars. The confrontation between east and west dominated world politics, diplomacy and military affairs in those years, and, as we shall see, was bound to affect economic development also. China, much the most populous country in the world, was at first part of the communist camp, but later took an independent line, though still adhering to a Marxist-socialist philosophy. She continued on this path even after the collapse of communist rule in the Soviet Union and her allies in 1989. Countries in neither orbit and not directly involved in that confrontation, mainly the less developed economies, became known as the ‘Third World’.

The second main development in the political field was de-colonization. While the loser countries, as was traditional, had to give up some territory, and Japan and Italy lost their colonies, this time the victors also ceded some of their ‘possessions’, by giving independence to their overseas colonies in a long-drawn-out process after the end of the war. The countries mainly affected were Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium and the United States. In the 1970s their example was followed by Portugal. The complex process of handing over power to indigenous governments was carried through peacefully in many cases; in others it was accompanied by armed conflict. This was particularly so where a large European minority, belonging to the former colonial power, refused to give up without a fight, as in (French) Algeria, where fighting went on from 1954 to 1962 or in (British) Southern Rhodesia, later renamed Zimbabwe, between its illegal declaration of independence in 1965 and 1979.

The process created a la...