Chapter 1

Introduction to naturalistic planting in urban landscapes

James Hitchmough and Nigel Dunnett

Although this book is potentially relevant to many urban contexts, it is most strongly aimed at the ‘public’ and ‘semi-public’ landscape. Some of these landscapes are public parks of one sort or another. The remainder are a difficult-to-characterise mix of spaces around public housing, commercial developments and institutions, car parks, left-over spaces from development, structure plantings of massed trees and shrubs, and strips along paths, roads and other corridors. Taken as a whole, these often very ordinary places are the landscapes we are most familiar with and which inform, and perhaps even shape, our attitudes to the world around us. In combination with private gardens, these urban spaces are also the landscapes where we have most of our first-hand experiences of ‘nature’. The design form of these landscapes is as diverse as their physical size, location and history. Examples of planting styles inspired by or derived from the picturesque, the gardenesque, the garden city, the modern movement, the municipal engineer, the ecological and, latterly, the community involvement style can all be found. Irrespective of how we now judge the aesthetic merits of the planting styles associated with these movements, in their day all were founded on the principle of being pleasing (as well as functional) to their creators and to the public at large.

Over the past couple of decades in Britain and other Western countries, the ongoing decline of public landscape maintenance, the realisation that funding will never again reach the levels of the nineteenth century or even early twentieth century, and the arrival of new social and environmental movements, has initiated a search for ‘new’ planting styles to help re-envigorate public landscapes. Views differ on what these might be, however the consensus is that these plantings should have relatively low-maintenance costs, be as sustainable as possible, taxonomically diverse, demonstrate marked seasonal change, and support as much wildlife as possible. These requirements fly in the face of traditional horticultural wisdom, which rightly argues that maintenance costs are generally proportional to planting complexity. We argue in this book that the only possible way to escape this restriction is to move away from wholesale reliance on traditional horticulturally-based plantings. By ‘horticultural’, we refer to plantings composed primarily of exotic species and cultivars, organised in culturally informed arrangements, rather than as ecologically-based plant communities, and managed relatively intensively to reduce competition between planted stock and spontaneously invading weeds, and to instead develop plantings that exploit ecological as well as horticultural processes and understanding (Figure 1.1).

It is reasonable to ask at this point whether the notion of maintaining a degree of quality in urban public planting should really be a point of concern—does urban horticulture, as represented in the diverse plantings of a well-maintained public park, for example, any longer have relevance to the general urban dweller? What is the benefit of introducing and maintaining ornamental or amenity vegetation in urban areas? Setting aside the purely functional roles of spatial subdivision and screening, and the obvious benefit of aesthetic delight, urban landscape plantings may become increasingly important to the health of the city environment and of those who live within it. With ever greater emphasis on the ‘compact city’ and higher densities of building in urban areas, good quality green spaces take on a special recreational, social and environmental role. There is mounting evidence that environmental quality is one of the factors that has a direct affect on the health and well-being of people in urban areas. This goes much further than a simple feeling of uplift at the sight of colourful flowering vegetation. In a wide-ranging study of urban green spaces in England, Dunnett et al. (2002) found that the quality of green spaces and their maintenance is likely to be viewed by local residents as one of the main indicators of general neighbourhood quality. There are therefore compelling arguments to be made that urban public planting has an important role to play in the general quality of life of people living in towns and cities, and this is before we even consider the benefits to wildlife and the functioning of a city’s ecological networks. It is all very well to make general statements like this about what is desirable, however the real challenge is how can these benefits be achieved in reality? And in particular, how can we both uphold the quality of plantings where they exist already but equally importantly, how can we extend the benefits of good urban plantings to those areas where they have been lost or may never have existed in the first place. It is hoped that this book provides some possible answers. Before going on to discuss the principles behind a more ecological approach to urban planting, it is first important to consider the social implications—what do people generally like to see in their surroundings and can an ecologically-informed approach provide this?

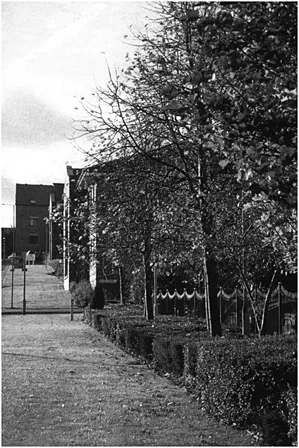

1.1

‘Horticultural’ landscape vegetation:

(a) blocks of evergreen shrubs, mechanically cut on a regular basis to maintain an artificial geometric shape, combined with mown grass and widely spaced trees. A very common and unfortunate contemporary approach to public landscape planting; and

(b) seasonal bedding—still regarded by many as the epitome of the craft of public horticulture. The extensive and vibrant colour of such bedding is achieved as a result of significant financial, labour and resource inputs

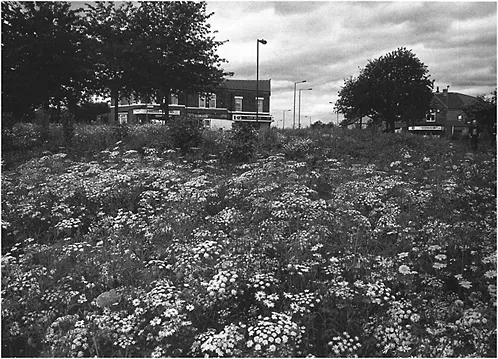

1.2

Direct-sown annual meadow 10 weeks after sowing in a Sheffield housing estate. Mixed native-exotic meadows provide high-impact, long-lasting colour and receive high public support

Public plantings—the social dimension

The nature conservation movement has seized upon the inability to adequately fund the maintenance of traditional horticulturally based plantings as an opportunity to increase the use of native ‘habitat’ plantings in urban landscapes. This has occurred to a considerable degree over the past 20 years in Britain, mirroring what had happened much earlier in some other European countries. This has been a very positive development, the most obvious product of which has been substantial areas of young woodlands, which, although rather ecologically depauperate, should enrich with time. This movement has not, however, been able to fully address the latent needs left unfulfilled by the decline of traditional horticultural planting. To do this, it is necessary to understand the reasons why these horticultural styles developed in urban public landscapes in the first instance.

In Britain, even at the height of the most ascetic planting traditions of the eighteenth-century English Landscape movement, highly colourful planting persisted within Pleasure Grounds (Laird 1999). People continued to pursue the horticultural exaggeration or ‘improvement’ of the nature they knew in the countryside. However abstracted, planting in private gardens nearly always demonstrates this exaggeration of nature; a latent desire for colour and drama appears to be an important part of the human psyche. This desire might be seen as a form of decadence, of wanting more than nature can offer, but why should this be considered to be regressive? Most lay people intuitively make judgements on the semi-natural vegetation around them on the basis of appearance, and always value some bits more than others, often because they are more colourful (Figure 1.2). If we are honest about it, and for a moment strip away learnt notions of ecological value, design values of rhythm and unity, and remove it from its context as part of scenery, on most days of the year semi-natural vegetation is often visually rather mundane. For individual people, this common, passive response to semi-natural vegetation can be papered over by taking on-board additional value systems that suppress or redefine these visceral aesthetic feelings. By doing this, tall rank grassland goes from being untidy and dull to a worthy vegetation involving a dramatic play of pulsating stems against the light, as well as being an important habitat for small mammals. Dullness or subtlety becomes reinterpreted as a virtue. There is merit in this reinterpretation, but we should not lose sight of how these values come together if we are not to be blind to other people’s perceptions. As a cultural institution, one of the key roles of the garden is in effect to gather together the plants, and the communities drawn from semi-natural vegetation, that are the most appealing to humans (Figure 1.3).

It is interesting that in Germany, the Netherlands and North America, the idea of nature-like, ecological planting was well founded by the end of the nineteenth century, and was vigorously pursued by landscape architects who were as strongly influenced by aesthetic as well as ecological and cultural outcomes. Art and design traditions would be invoked to package nature to look good and, by doing so, more urban people would be able to embrace it. These ideas are discussed in greater detail by Jan Woudstra in Chapter 2. Awareness of these foreign traditions was limited in Britain, and even when present, became lost or perhaps obscured towards the end of the twentieth century in the enthusiasm to embrace a more literal ‘native’ urban nature. In this later habitat restoration inspired movement, art and culture, and aesthetics play little or no conscious part, putting back what has been lost being the key measure of success.

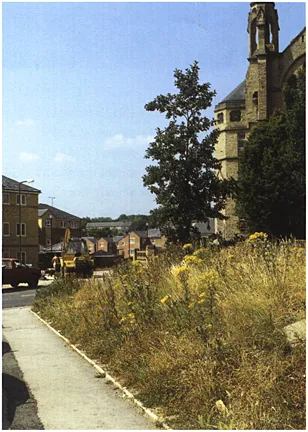

1.3

Spontaneous urban vegetation. An important habitat resource, yes, but is it appreciated as such by the general public?

1.4

Ponds and lakes in urban parks offer great potential for dramatic planting; Parc Andre Malreaux, Paris

Although in Britain many of the urban Wildlife Trusts maintain a very liberal perspective on conservation, grounded in social awareness, overall habitat restoration is a conservative rather than a creative discipline, sometimes motivated by rigid moral assumptions about what is right. Proponents adhere to the philosophy that if you put back the species that were there before humans destroyed them, the aesthetics will sort themselves out. In any case, with such moral authority on your side, there is no need to consider whether such vegetation positively enriches the lives of the public. This philosophy is less troublesome to apply in toto in rural landscapes that are less subject to intense public scrutiny but is sometimes problematic in urban landscapes founded on different cultural assumptions. Whilst they share many common goals, these two traditions of using nature-like landscapes in urban landscapes are sometimes difficult to reconcile in practice.

This impasse is perhaps the ideal place to tackle exactly where a book about how to design and manage ecologically informed, nature-like planting fits in practice and philosophy. Books written by a collective of authors are often awkward in that it is often impossible for everyone to sign up to the same principles. The idea that unites all of the contributors of The Dynamic Landscape is that, in urban contexts, designed, nature-like vegetation must be strongly informed by aesthetic principles if it is to be understood and valued by the public at large (Figure 1.4).

This prompts the question that Anna Jorgensen explores in detail in Chapter 11: what do we know about how the public appreciate nature-like vegetation? Do people actually like this type of vegetation, and if so why and if not why not? There is a tendency for all professional groups and disciplines to believe that their perceptions of worth and beauty are intrinsically valid, and that those who hold different views are at best poorly informed. Such attitudes are particularly strongly held within nature conservation, where attitudes are increasingly shaped by a sense of a moral outrage. Aesthetic perceptions and preferences do however differ enormously between individuals, peer groups and cultures, with truths being relative rather than absolute. If it were not for this psychological quirk our species would have no need for landscape architects and related disciplines to exist. We would happily live surrounded by whatever vegetation sprouted spontaneously from the soil. Our own experience of some of the ecologically-based vegetation we have created is that, to many lay observers, until it flowers and, in some cases, even when flowering, it is indistinguishable from weed communities! On the other hand, it is interesting how readily some aesthetic preferences change, through experience and learning. These values are not fixed and this process can be readily observed, for example, as landscape design students progress from the first to final year.

There has been much research on landscape perception and preference in rural situations. Most people seem to like ‘natural scenes’ in a rural context, however it is unsound to try to apply this verbatim to urban spaces. There has been little work at the level of individual plant communities. Culture, context and familiarity seem to be very important, but, in general, the disorderly appearance of nature-like landscapes seems to be challenging in many urban situations. This suggests that nature-like vegetation which is not designed to make it clear that it is meant to be there and is cared for, may not be widely valued. It is certainly naïve to imagine that 100 m2 of vegetation ‘lifted out’ of a semi-natural landscape scene will be perceived in the same way when placed in an urban context. In most cases, the transformation will only be successful where the scene is ordered in some way, the viewer provided with cues, or the visual intensity exaggerated by design, as previously mentioned.

Given our strong concern for the aesthetics of landscape, this book adopts a pluralistic approach to nature-like planting. The authors suggest that it is possible to identify at least three broad strands within nature-like planting, which, to some degree, are encompassed by the authors within this text. A more detailed exploration of these strands is provided in the context of practice by Noel Ki...