- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Origins and Development of the Dutch Revolt

About this book

The Dutch revolt against Spanish rule in the sixteenth century was a formative event in European history. The Origins and Development of the Dutch Revolt brings together in one volume the latest scholarship from leading experts in the field, to illuminate why the Dutch revolted, the way events unfolded and how they gained independence. In exploring the desire of the Dutch to control their own affairs, it also questions whether Dutch identity came about by accident.

The book makes the most recent research available in English for the first time, focusing on:

* the role of the aristocracy

* religion

* the towns and provinces

* the Spanish perspective

* finance and ideology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Origins and Development of the Dutch Revolt by Mr Graham Darby,Graham Darby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Narrative of events

Graham Darby

Valois Burgundy

The Netherlands — from the Dutch for 'Low Countries' — refers to the counties, duchies and principalities around the mouth of the River Rhine on the North Sea coast and corresponds roughly to what is today Holland, Belgium, Luxemburg and a small part of northern France (Artois). It is a geographical rather than political term, since until 1548 it did not form a political unit — nor indeed a cultural or ethnic unit. However, in the late medieval period a number of these territories came to be grouped together (but were not in any way united) by sharing a single ruler, the Valois duke of Burgundy.

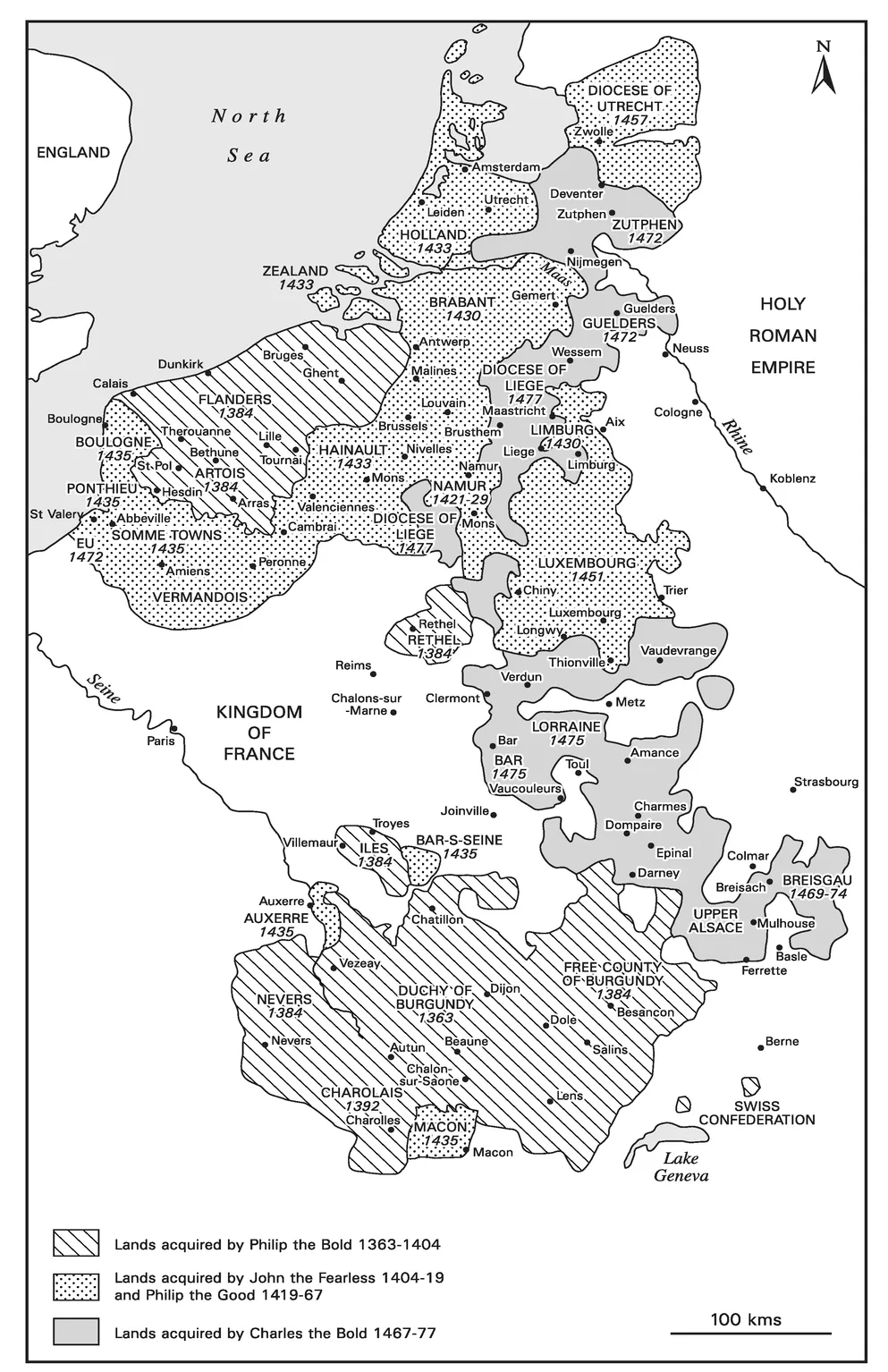

During the course of the Hundred Years War, King John II of France assigned the duchy of Burgundy as an apanage to his fourth son, Philip the Bold. Through Philip's marriage to Margaret the heiress of the count of Flanders, he gained possession, after the death of his father-in-law in 1384, of the counties of Flanders, Walloon Flanders, Artois and Rethel, the towns of Antwerp and Mechelen, and also the county of Nevers and the free county of Burgundy (Franche-Comte). However, far from representing an extension of French influence into this area, the dukes of Burgundy proved to be interested in building up their own political Dower.

Duke John the Fearless succeeded to all his father's lands in 1404 and under his son Philip the Good (ruled 1419—67) there was a considerable expansion of territory — through inheritance, war and purchase. The counties of Namur, Holland, Zeeland and Hainault, as well as the duchies of Brabant, Limburg and Luxemburg were all added. Duke Charles (1467—77) temporarily added Gelderland.

In the 1430s Duke Philip attempted to give the territories a degree of institutional centralisation by creating the States General, an assembly of representatives from the various provincial States, a central Chamber of Accounts and the Order of the Golden Fleece (a distinction designed

Map 1 Valois Burgundy.

to bind the various magnates to the court), all of which came to be centred in Brussels. Under Philip the Good, some territories were placed under the duke's lord lieutenant or 'stadholder' as provincial governors were called. Despite these developments, the component parts of the Burgundian Netherlands retained considerable autonomy.

The expansion of the Burgundian Netherlands came to a sudden end in 1477 with the death of Duke Charles at the battle of Nancy. The original duchy of Burgundy and some other territories reverted by feudal law to King Louis XI of France, leaving the remainder to Charles's widow Margaret of York, whose step-daughter Mary married Maximilian of Habsburg. Margaret and Mary were faced with revolt everywhere and had to concede the Great Privilege, a charter which confirmed that the provinces' 'liberties', separate customs and laws, would be guaranteed and gave the States General of the Burgundian Netherlands the right to gather on their own initiative whenever they saw fit, as well as drastically curbing the power of the ruler in fiscal and military matters. Holland and Zeeland obtained their own separate Great Privilege. The Valois dukes of Burgundy:

| Philip the Bold | 1363-1404 |

| John the Fearless | 1404-1419 |

| Philip the Good | 1419-1467 |

| Charles the Bold | 1467-1477 |

The Habsburg Netherlands

Mary died in 1482 and Maximilian ruled as regent for their son Philip. Rale by the Habsburgs to some extent saved the Netherlands from absorption by France but. by 1487 the regent was faced with a general revolt which, though crushed, led to the loss of Gelderland. In 1493 Maximilian became the Holy Roman Emperor and his son Philip was proclaimed of age. At his inauguration in 1494 Philip the Fair had the Great Privilege almost entirely abrogated, though its constitutional provisions remained an aspiration for subsequent generations.

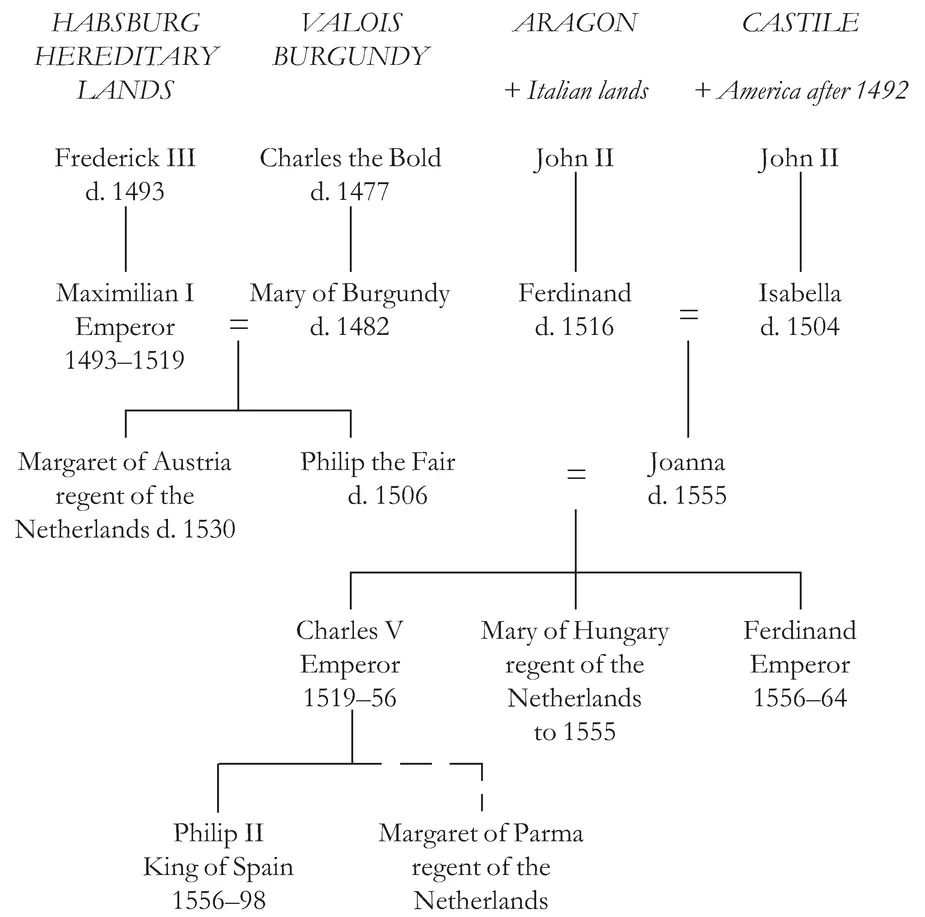

The regimes of Philip I (1493—1506) and the subsequent regency of Margaret of Austria (1506—15) were periods of relative stability, though military activity north of the rivers failed to recover Gelderland or extend authority into Groningen and Friesland. Charles Habsburg — known as Charles of Luxemburg at this point — was declared of age as ruler of the Habsburg Netherlands in 1515 but became King Charles I of Spain in 1516 and Emperor Charles Yin 1519, so that the Netherlands were now

Figure 1.1. The Habsburg inheritance.

NB: Margaret of Austria, regent of the Netherlands, was in fact two years younger than Philip the Fair and technically should be shown on the right. However, this is a simplified genealogy.

only a small part of a much larger empire. Charles, who had grown up in the Netherlands, was compelled to delegate power first to his aunt Margaret again (regent 1517—30) and then to his sister Mary of Hungary from 1531.

Despite this, territorial expansion continued, largely financed by Holland,1 with the acquisition of Friesland, Utrecht and Overijssel in the 1520s. In 1531, Charles spent most of the year in Brussels reorganising the government. He set up a Council of State of magnates and jurists, a Privy Council of professional bureaucrats and renewed the Council of Finance. Provinces were grouped together under the same provincial governors or stadholders, though these were not felt necessary for Brabant and Mechelen. Thus Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht (and later Gelderland) were grouped together, as were Flanders, Walloon Flanders and Artois; and later so too were Friesland, Groningen, Drenthe and Overijssel.

Groningen and Drenthe were annexed in 1536 and Gelderland was finally conquered in 1543. In 1548, Charles persuaded the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire in the Treaty of Augsburg2 to recognise the Habsburg Netherlands as a separate and single entity and laid down that it would pass to the emperor's heirs in perpetuity. This 'Pragmatic Sanction' was then endorsed by all seventeen provinces in 1549. At this juncture the seventeen provinces3 consisted of Holland, Zeeland, Brabant, Flanders, Walloon Flanders, Artois, Luxemburg, Hainault, Mechelen, Namur, Groningen, Friesland, Gelderland, Limburg, Tournai (which Charles had added in 1521), Utrecht and Overijssel (this included Drenthe). However, a declaration of unity was one thing, reality another, and it is interesting to note that five of the seven provinces which later became the Dutch Republic (i.e. Friesland, Utrecht, Overijssel, Groningen and Gelderland) were quite recent additions. Indeed Habsburg control in Groningen, Overijssel and Gelderland never amounted to much and constituted something of a divide between the north-east and the rest.

Disunited provinces

Thus the process of unification was more apparent than real and this was reflected in the fact that the ruler did not have a single title but many. Thus he was the duke of Brabant, the count of Flanders, the lord of Friesland, etc., designations that emphasised the confederate nature of the Low Countries. In addition, there were physical obstacles to unification.4 The provinces of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht and Friesland were practically surrounded by the sea and cut off from the 'heartland provinces' of Hainault, Artois, Flanders and Brabant, by numerous rivers, dikes and lakes. The eastern and north-eastern provinces of Limburg, Luxemburg, Gelderland, Overijssel, Drenthe and Groningen were cut off from the rest by dunes, bogs and heaths and by the independent ecclesiastical principality of Liege. There were linguistic divisions too: the central government and the court used French which was prominent in the south, but the majority to the north spoke varieties of Dutch.5 There was also something of a divide in terms of religion. Despite initial interest in new religious ideas coming from the German lands, the repressive regime had prevented evangelicals in the towns of

Map 2 The Habsburg Netherlands.

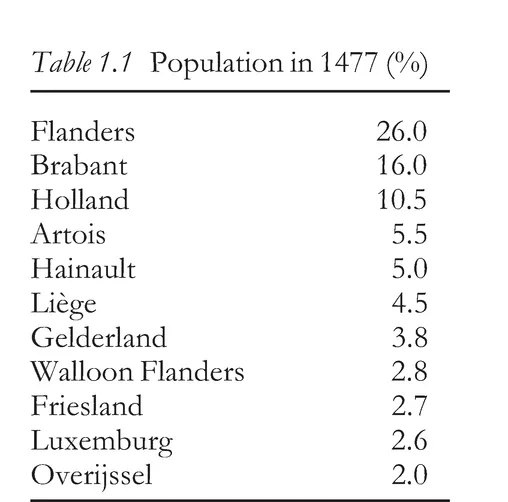

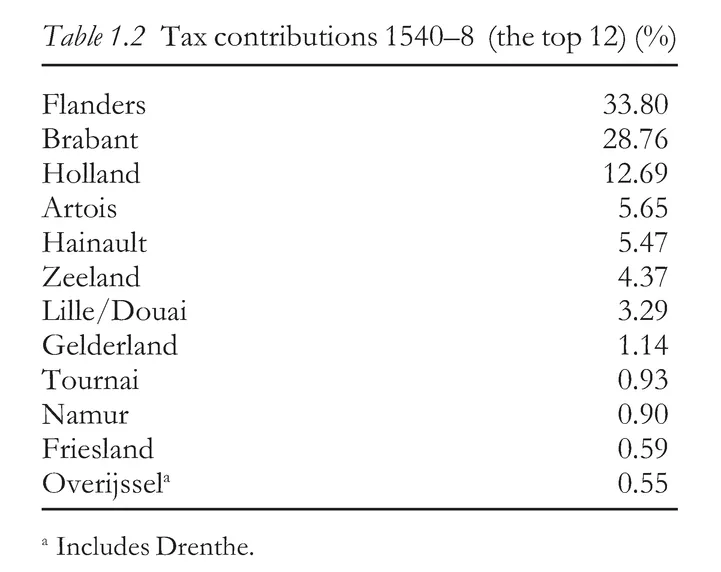

the Low Countries, with the notable exception of the Anabaptists, from developing schismatic congregations. But if the persecution came close to extinguishing the evangelical groups in the 1540s, by forcing suspected dissidents to flee the country, it contributed to the growth of Calvinist churches abroad. These in turn provided leadership for the small Calvinist congregations established in the larger southern towns after 1555. The repressive regime, associated with the Inquisition and mistakenly with its Spanish namesake, was widely resented by the elites because it encroached on privileges intended to provide justice and protect property. In Flanders and Brabant religious passions became most inflamed; further away from this epicentre of confessionalisation the confrontation between Catholics and Calvinists was altogether more muted. In addition to the historical, geographical, linguistic and even in some cases religious differences, there were also marked differences in terms of population and wealth, as a glance at Tables 1.1 and 1.2 will show.

Quite clearly Flanders, Brabant and Holland were more advanced in terms of population, urbanisation and wealth. Half of Holland's population was urban and the even spread of its distribution across Dordrecht, Haarlem, Leiden, Amstersdam, Delft and Gouda reflected a wide dispersal of wealth and had some significance for the subsequent development of Dutch politics and society. Prosperity was derived from the bulk freightage and the herring fishery. By contrast the prosperity of the southern urban economy sprang from the rich trades — textiles, spices, metal and sugar — and of course from the derived finished goods.

The towns valued their political autonomy and guarded their privileges. The government was dominated by a group known as regents — mostly successful financiers and merchants. They were never an oligarchy defined by birth or status but did become a closed political group.6 In

addition there were also about 4000 nobles in the Netherlands. The grandees — consisting perhaps of only about twenty families — were large landowners and had international connections. These magnates tended to reside in the south. The lesser nobility were not so well-off and their lifestyle was sometimes little better than that of a wealthy peasant. What is apparent from all this, then, is the variety and complexity of the Netherlands and the difficult task the Habsburgs had set themselves in trying to weld these lands together into a single political unit.

From the 1540s Emperor Charles V was once again drawn into prolonged warfare with France. As a consequence the provinces were subjected to new heavy burdens of taxation and because of the growing success of the Netherlands economy, the regime was increasingly inclined to rely on this area. However, far from increasing Habsburg control, the regime in effect assigned a larger and larger role to the States in the collection and management of finance. This was to have great significance in the future. In the meantime though, by the 1550s disaffection was beginning to spread, military expenditure doubled and the deficit in 1557 was seven times that of 1544. But by that time the Netherlands had a new ruler.

A new ruler

Prince Philip, son and designated heir of Charles V in the Netherlands, was introduced to his future subjects by means of a royal tour in the spring of 1549. At that time he recognised and confirmed the 'Joyous Entry' a list of constitutional liberties and privileges dating back, in the case of Brabant, to 1356. When Philip inherited the provinces in bis own right in 1555 after Charles V's abdication, he inherited territories that had clearly become used to the judicial and financial independence they enjoyed under his father.7 Moreover, the grandees in the Council of State had also developed an exaggerated idea of the level of participation they had been allowed in the internal administration of the provinces by the successive female resents, Margaret and Marv.

Charles V had appointed the duke of Savoy as regent and determined the composition of the Council of State, but despite becoming king of Spain in 1556 Philip decided to remain in Brussels and exercised power without reference to the Council of State. His colossal tax demands were initially resisted, but the States General finally agreed to them in 1558, by which time the war with France was virtually over and Philip was turning his attention to the problems of Spain and Islam. He left for Spain in 1559 never to return.

The collapse of authority, 1559-1566

Whether or not Philip's departure was a wise decision would depend upon how events unfolded subsequently. The situation in the Netherlands was undoubtedly potentially dangerous. The debt was immense, the States General in a difficult mood, the newly acquired provinces uncooperative, the nobles dissatisfied, the religious situation further complicated by the sudden growth of Calvinism, and the duke of Savoy would not act as regent. Accordingly, Philip appointed his half-sister, Margaret of Parma, as regent. William of Orange was made stadholder of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht, and the count of Egmont of Flanders and Artois — but power came to reside with Cardinal Granvelle, a fact that was soon resented by the magnates.

This clash of personalities came to a head over the issue of ecclesiastical reorganisation. Originally devised by Charles V, the plan to create fourteen new bishoprics and three archbishoprics (with Granvelle as the primate) was long overdue, but threatened a wide range of vested interests (a career in the church was a traditional avenue for younger sons of nobles without lands of their own) and threatened a new wave of persecution. Following a wave of discontent, the regent petitioned Philip for Granvelle's removal in 1563 and he was withdrawn the following year. Philip also suspended his ecclesiastical reform programme.

This looked like a victory for Orange and the magnates and it seemed to spell the end of the Inquisition. The magnates favoured greater religious freedom because it was felt persecution might lead to civil war, as in France; persecution interfered with established laws and procedures; and they saw no reason why differences of belief should be treated so harshly. However, Philip II was not prepared to compromise any further. In two letters written from his country house in the Segovia Woods and signed on 17 and 20 October 1565 he made his position quite clear. There was to be no amelioration of the heresy laws and no increase in power of the Council of State. It was a clear challenge to the nobles to obey and enforce government policy and it provoked a wave of protests.

A group of lesser nobles led by Hendrik van Brederode took matters into their own hands and formed the League of Compromise in November 1565 to bring about a relaxation of the heresy laws. In April 1566 about 400 of them presented their Petition of Compromise...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures, tables and maps

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Chronology

- Frontispiece

- Introduction

- 1 Narrative of events

- 2 Alva's Throne — making sense of the revolt of the Netherlands

- 3 The nobles and the revolt

- 4 Religion and the revolt

- 5 The towns and the revolt

- 6 The grand strategy of Philip II and the revolt of the Netherlands

- 7 Keeping the wheels of war turning: revenues of the province of Holland, 1572—1619

- 8 From Domingo de Soto to Hugo Grotius: theories of monarchy and civil power in Spanish and Dutch political thought 1555-1609

- Index