- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pacific Asia

About this book

Pacific Asia - from Burma to Papua New Guinea to Japan - is the most dynamic and productive region in the developing world, the result of an economic explosion fuelled by industrial activity. This is where the Green Revolution began, where more women are employed in factory work than anywhere alse; the region is also the most predominately socialist in the Third World. David W. Smith assesses Pacific Asia both in terms of its historical development and the present global system, placing general development issues in their local contexts. The book will be an invaluable introduction to the region.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Pacific Asia by David W. Drakakis-Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: the regional character

Defining Pacific Asia

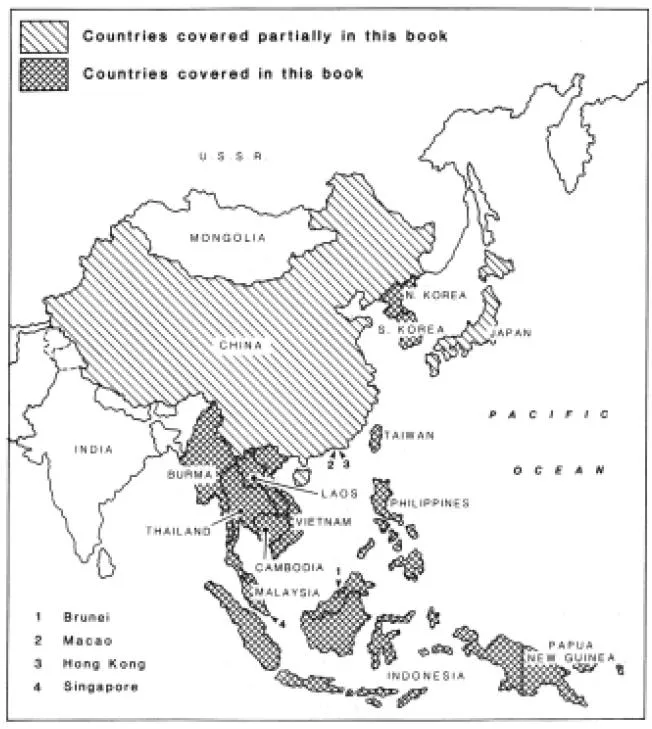

The term Pacific Asia is relatively new and will be used in this book to refer to the developing countries identified in Figure 1.1. Japan and China will largely be excluded from the discussion: the former because it is now one of the most advanced nations in the world and no longer forms part of the developing countries of the region; the latter because it is so large and complex that another book in this series (forthcoming) is devoted to it. Clearly, however, a regional text on Pacific Asia cannot ignore two important states and the later chapters, particularly Chapter 2, give full recognition to their role in shaping the character of Pacific Asia.

In the past the region covered by this volume has been known, in part or as a whole, by a variety of descriptive terms, viz. East of Suez, the Far East, East Asia, Southeast Asia and so on. The emergence of the term Pacific Asia during the 1980s is a belated recognition of the fact that the global orientation of the countries in the region has changed. Until the Second World War this was a region dominated by colonial interests, most of which were still European. By the 1950s, however, that European influence had ended and the dominant power in the region was the United States.

Economic exploitation and political pressure during the 1950s and 1960s were, therefore, predominantly from across the Pacific. Since the 1970s, however, Japan has emerged as a leading political and economic nation, successfully challenging the United States for power and influence amongst the capitalist economies in the region. In short, the region now looks east and has become much more conscious of its geographical position in relation to the Pacific rather than to Europe. Terms such as ‘Near’ or ‘Far’ East are thus anachronisms since they described geographical location with regard to the European colonial powers. We are about to enter the Pacific century and this part of Asia has renamed itself in preparation.

Figure 1.1 Pacific Asia: political units covered in this text

Clearly, we cannot undertake a study of Pacific Asia without emphasizing its global ties, both past and present, and the role it plays in the world economy. And yet the region is not uniform in character. There are sharp political divisions between socialist and capitalist states, whilst massive socio-economic contrasts also exist between the intensive industrial societies of Hong Kong or Singapore and the impoverished upland regions of Southeast Asia. Each country has developed in its own fashion, has its own set of resources, has reacted differently to colonialism, has been drawn into the world economy in varied ways, and has its own preoccupations in terms of development.

Yet this immensely varied set of nations does form part of the global economy and shares a common set of developmental problems – the legacies of colonialism, uneven regional development, rapid urbanization, the need for economic diversification and so on.

Given such circumstances it would be futile either to discuss each of these issues for the region as a whole, since differences are too marked, or to describe each country in turn, using an old-fashioned regional approach which runs through physical features, climate, resources, agriculture, etc. Instead, the general background to common contemporary developmental issues will first be examined (the global setting and internal diversity in this chapter; the historical evolution of the present situation in Chapter 2). This will be followed by discussion of selected major issues in the setting of just one or two countries, in order to illustrate how common regional and global development problems must be placed in both a national and local context before the real policy issues can be discussed.

Pacific Asia in its global setting

Trade

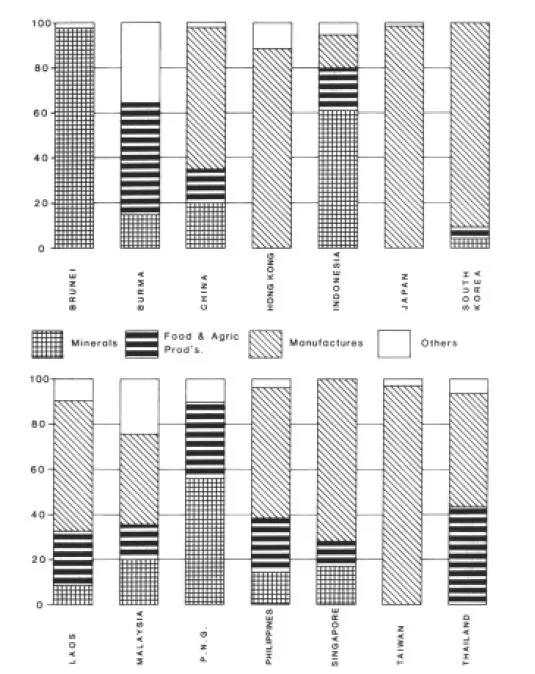

In the colonial period, the principal trade links between Pacific Asia and the rest of the world, primarily Europe, were essentially those of commodity exports (industrial raw materials and some foodstuffs) and manufactured imports. The present world trading system maintains vestiges of that era in the sense that many countries in Pacific Asia still rely on primary commodity exports for much of their foreign exchange earnings. However, as Figure 1.2 also indicates, manufacturing exports are now important throughout the region. Figure 1.2 does not reveal the complete picture, as it does not include earnings from the export of services: this is becoming increasingly important for the more advanced states in the region, such as Singapore and Hong Kong (see Chapter 7).

Figure 1.2 Pacific Asia: structure of exports

In general, the region’s trade has increased steadily over the last 25 years, although it has slowed down during the recession of the 1980s, increasing threefold between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s. Overall, Pacific Asian trade (excluding Japan and China) now accounts for almost 10 per cent of all Third World trade.

Figures such as these illustrate the nature of Pacific Asia’s growing integration with the world economy but, of course, there are considerable variations within the region. Burma, for example, has withdrawn into itself and its overall trading activity has steadily fallen over the years. Moreover, although the more industrialized states may cluster at the top of the aggregate trading lists, it would be unwise to forget that the sheer size of a nation will also be important in trading activity. Thus, although Indonesia’s per capita prosperity is less than a third of that of the neighbouring state of Malaysia, its exports are larger.

Given the attempts of most countries in Pacific Asia to diversify from primary exports into manufacturing, it is not surprising that the region’s imports are dominated by two categories – fuel and capital equipment. With regard to the latter, most of the countries in Pacific Asia spend at least one-quarter to one-third of their import bill on production machinery, and this includes the more industrialized states; some spend an even higher proportion. With regard to fuel, the region is sharply polarized between the energy rich, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, and the energy poor, which covers all of the major industrial exporters (including Japan). The result is a net flow of energy across the region from southeast to northwest.

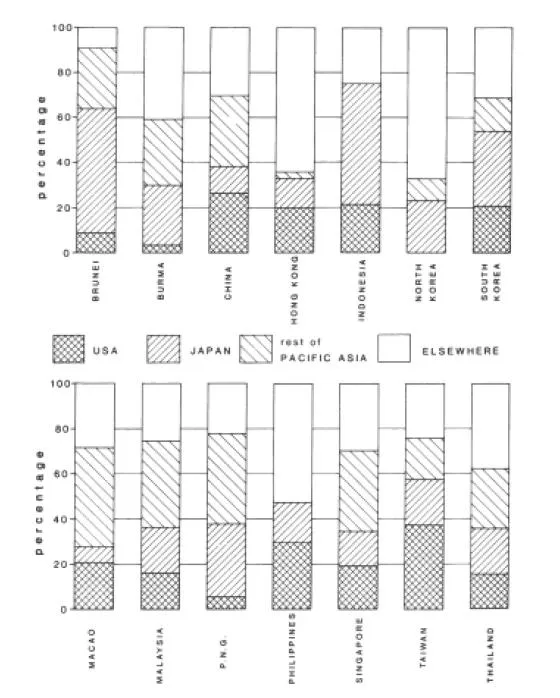

But perhaps the most revealing aspect of regional trends in trade is not so much the overall level or even the principal type of exports and imports, but the direction of trading activity. Figure 1.3 reveals clearly how the formerly dominant European destinations have been overwhelmingly replaced by Pacific links. For the most part this involves Japan and the United States, with the former being the leading trading focus for the region since the mid-1970s. To be sure, some of the socialist states trade mainly with the communist bloc but even these have witnessed a growth in their trading activity with Japan. A slightly different picture emerges if the volume of trade is broken down into specific categories. For example, despite the overall trading dominance of Japan, the United States is still by far the most important market for the export of manufactured goods.

The corollary of much of this trading activity, particularly in exports, is the inward flow of investment into the region. All types of financial flows into Pacific Asia have increased over the last 20 years but, in general, private flows have increased far more rapidly than public or government flows. As a result, foreign investment has become a much more prominent proportion of total investment, particularly in those countries favoured by the international investors. Singapore, in particular, has been a magnet for such financial flows, so much so that half of its gross domestic product is funded this way.

Figure 1.3 Pacific Asia: major trading partners

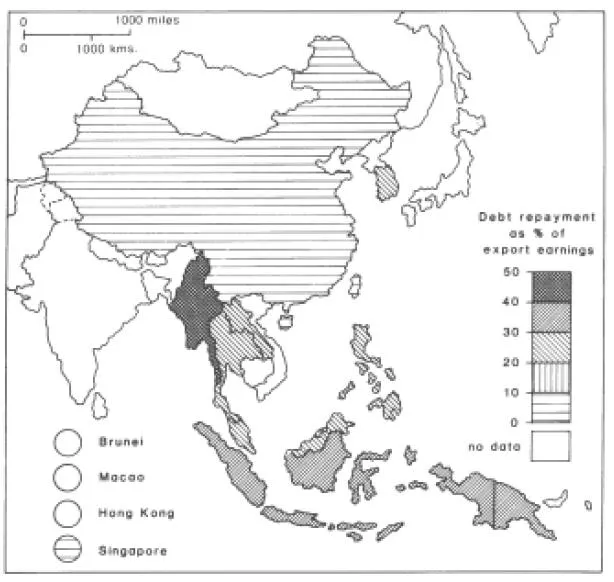

The less desirable consequence of overseas loans, rather than investment, is debt and many of the countries in the Pacific Asian region face a mounting debt crisis as a result of borrowing during times of expansion and not being able to service the interest during the lean years of the 1980s (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Pacific Asia: debt repayment as a percentage of export earnings

Resources

Clearly the investment and expansion summarized in the previous section is attracted by the resources of the region. The region is reasonably well endowed with major mineral and energy resources, albeit in a somewhat erratic distribution. There are also rich forests and fertile soils but there is little point in mapping these attributes as their exploitation has depended very much on the principal resource of the region – its people. It is their inventiveness and energy over the years that have transformed riverine flood plains or seasonally dry regions into fertile and productive areas through irrigation and drainage, and it is their labour that currently creates profit where no physical resources exist.

Pacific Asia is also important in terms of physical resource output, although it must be admitted that it is countries that do not lie within the purview of this book, such as China, Australia and the Soviet Far East, from which most of the regional output derives. Nevertheless, major oil resources are currently being exploited and exported in Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia, whilst several countries feature in the list of top ten producers of nickel (Indonesia, Thailand) and tin (Malaysia and Thailand).

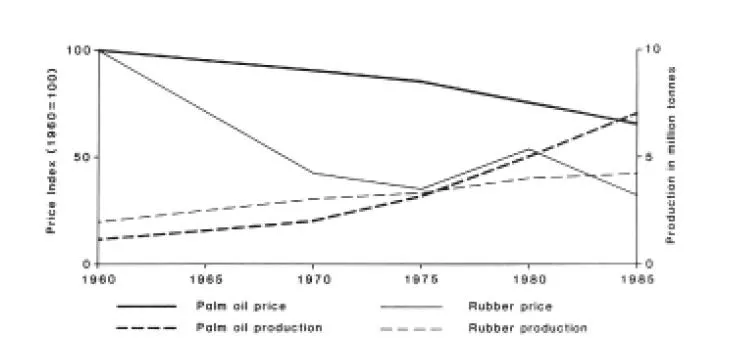

Agricultural exports are also substantial, with the region dominating world production of a number of key industrial commodities such as rubber, palm oil and copra, as well as continuing to produce its traditional export crops of rice, tropical fruits and various spices. One problem with industrial agricultural resources has been the fact that prices have fallen dramatically over the last few decades. Far from discouraging production, this has pushed it to ever-higher levels in order to ensure that revenues are retained (Figure 1.5) – often at the expense of other environments (see Chapter 3).

Of course it can be fairly claimed that the intensity of development of both agriculture (and industry) has been the consequence of sheer population pressure on resources. Although death rates began to fall in the late colonial period, birth rates stayed high almost everywhere until the 1970s. Even so, the rate of natural increase is still high in many countries and has posed serious problems for the governments of Indonesia, the Philippines and other states (see Chapter 5).

The nature of the human resources of a region are, however, dependent upon much more than sheer numbers. The quality of life and the labour potential is inextricably linked to the levels of education, nutrition and health care (Table 1.1), all of which vary enormously, not necessarily correlating to the level of development (as indicated by GNP). The nature of this variation is discussed below. There are, however, less quantifiable aspects to the human and physical resources of the region. These might relate, for example, to the cultural mix, the architectural legacies of the past and the beautiful scenery. The variety of each encompassed in Pacific Asia is probably far more extensive than in any other part of the developing world – a feature indicated by the massive growth in tourism. On the other hand, both the human and physical resources in the region have a certain fragility, due in part to their complexity and symbiotic relationship with one another. One consequence, therefore, of the rapid changes of the post-independence years has been both environmental and human exploitation, subjects which are investigated in Chapter 3.

Figure 1.5 Palm oil and rubber: price and production trends 1960–85

The political situation

In many ways the variations in the development process in Pacific Asia reflect its political composition. It is perhaps an oversimplification merely to divide the region into its communist and capitalist components. The socialist states are all very different in their nature, with China and Vietnam constituting traditionally bitter enemies; North Korea pursuing a dated but not unsuccessful Stalinist development strategy; and Burma blending socialism and Buddhism into a unique brand of isolationist stagnation. Nor can it be said that the capitalist states are any more unified. The principal internal alliance is ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) but it has taken a long time to overcome the traditional antipathy and suspicion between these Southeast Asian neighbours.

Table 1.1 Pacific Asia: selected indicators of growth and development

1. Introd...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Plates

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction: The Regional Character

- 2. An Historical Geography of Pacific Asia

- 3. Physical and Human Resource Management: Malaysia and Papua New Guinea

- 4. Rural and Regional Development

- 5. Population Growth and Mobility

- 6. Ethnic Plurality and Development In Malaysia

- 7. Industrialization and the Four Little Tigers

- 8. Urbanization and Urban Planning In Hong Kong

- 9. Gender and Development: Migration, Urbanization and Industrialization In Taiwan

- Further Reading and Review Questions