- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Readings from Emile Durkheim

About this book

Emile Durkheim is regarded as a founding father of sociology, and is studied in all basic sociology courses. This handy textbook is a key collection of translations from Durkheim's major works.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Readings from Emile Durkheim by Prof Kenneth Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One Sociology—its nature and programme

Reading 1 Sociology and the Social Sciences

DOI: 10.4324/9780203337141-2

Edited and reprinted with permission from: M.Traugott (ed.), Emile Durkheim On Institutional Analysis, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1977, pp. 76–83. Originally published as ‘Sociologie et sciences sociales’, in De la Méthode dans les sciences, Paris, Alcan, 1909, pp. 259–285.

Now on first consideration, sociology might appear indistinguishable from psychology; and this thesis has in fact been maintained, by Tarde, among others. Society, they say, is nothing but the individuals of whom it is composed. They are its only reality. How, then, can the science of societies be distinguished from the science of individuals, that is to say, from psychology?

If one reasons in this way, one could equally well maintain that biology is but a chapter of physics and chemistry, for the living cell is composed exclusively of atoms of carbon, nitrogen, and so on, which the physico-chemical sciences undertake a study. But that is to forget that a whole very often has very different properties from those which its constituent parts possess. Though a cell contains nothing but mineral elements, these reveal, by being combined in a certain way, properties which they do not have when they are not thus combined and which are characteristic of life (properties of sustenance and of reproduction); they thus form, through their synthesis, a reality of an entirely new sort, which is living reality and which constitutes the subject matter of biology. In the same way, individual consciousnesses, by associating themselves in a stable way, reveal, through their interrelationships, a new life very different from that which would have developed had they remained uncombined; this is social life. Religious institutions and beliefs, political, legal, moral, and economic institutions—in a word, all of what constitutes civilization—would not exist if there were no society.

In effect, civilization presupposes cooperation not only among all the members of a single society, but also among all the societies which interact with one another. Moreover, it is possible only if the results obtained by one generation are transmitted to the following generation in such a way that they can be added to the results which the latter will obtain. But for that to happen, the successive generations must not be separated from one another as they arrive at adulthood but must remain in close contact, that is to say, they must be associated in a per-manent fashion. Thus, this entire, vast assembly of things exists only because there are human associations; moreover, they vary according to what these associations are, and how they are organized. These things find their immediate explanation in the nature of societies, not of individuals, and constitute, therefore, the subject matter of a new science distinct from, though related to, individual psychology: this is sociology.

Comte was not content to establish these two principles theoretically; he undertook to put them into practice, and, for the first time, he attempted to create a sociological discipline. It is for this purpose that he uses the three final volumes of the Cours de philosophie positive. Little remains today of the details of his work. Historical and especially ethnographic knowledge was still too rudimentary in his time to offer a sufficiently solid basis for sociological inductions. Moreover, as we shall see below, Comte did not recognize the multiplicity of the problems posed by the new science: he thought that he could create it all at once, as one would create a system of metaphysics; sociology, however, like any science, can be constituted only progressively, by approaching questions one after another. But the idea was infinitely fertile and outlived the founder of positivism.

It was taken up again first by Herbert Spencer. Then, in the last thirty years, a whole legion of workers arose—to some extent in all countries, but particularly in France—and applied themselves to these studies. Sociology has now left behind the heroic age. The principles on which it rests and which were originally proclaimed in a very philosophical and dialectical way have now received factual confirmation. It assumes that social phenomena are in no way contingent or arbitrary. Sociologists have shown that certain moral and legal institutions and certain religious beliefs are identical everywhere that conditions of social life are identical. They have even been able to establish similarities in the details of the customs of countries very distant from each other and between which there has never been any sort of communication. This remarkable uniformity is the best proof that the social realm does not escape the law of universal determinism.

II The Divisions of Sociology: The Individual Social Sciences

But if, in a sense, sociology is a unified science, still it includes a multiplicity of questions and, consequently, a multiplicity of individual sciences. Therefore, let us examine these sciences of which sociology is the corpus.

Comte already felt the need to divide it up; he distinguished two parts: social statics and social dynamics. Statics studies societies by considering them as fixed at a given point in their development; it seeks the laws of their equilibrium. At each moment in time, the individuals and the groups which shape them are joined to one another by bonds of a certain type, which assure social cohesion; and the various estates of a single civilization maintain definite relations with one another. To a given degree of elaboration of science, for example, corresponds a specific development of religion, morality, art, industry, and so forth. Statics tries to determine what these bonds of solidarity and these connections are. Dynamics, on the contrary, considers societies in their evolution and attempts to discover the law of their development. But the object of statics as Comte understood it is very indeterminate, since it arises from the definition which we have just. given; moreover, he devotes only a few pages to it in the Cours de philosophie. Dynamics take up all the rest. Now the problem with which dynamics deals is unique: according to Comte, a single and invariable law dominates the course of evolution; this is the famous Law of Three Stages. The sole object of social dynamics is to investigate this law. Thus understood, sociology is reduced to a single question; so much so that once this single question has been resolved—and Comte believed he had found the definitive solution—the science will be complete. Now it is in the very nature of the positive sciences that they are never complete. The realities with which they deal are far too complex ever to be exhausted. If sociology is a positive science, we can be assured that it does not consist in a single problem but includes, on the contrary, different parts, many distinct sciences which correspond to the various aspects of social life.

There are, in reality, as many branches of sociology, as many individual social sciences, as there are different types of social facts. A methodical classification of social facts would be premature and, in any case, will not be attempted here. But it is possible to indicate its principal categories.

First of all, there is reason to study society in its external aspect. From this angle, it appears to be formed by a mass of population of a certain density, disposed in the face of the earth in a certain fashion, dispersed in the countryside or concentrated in cities, and so on. It occupies a more or less extensive territory, situated in a certain way relative to the seas and to the territories of neighbouring peoples, more or less furrowed with waterways and paths of communications of all sorts which place the inhabitants in more or less intimate relationship. This territory, its dimensions, its configuration, and the composition of the population which moves upon its surface are naturally important factors of social life; they are its substratum and, just as psychic life in the individual varies with the anatomical composition of the brain which supports it, collective phenomena vary with the constitution of the social substratum. There is, therefore, room for a social science which traces its anatomy; and since this science has as its object the external and material form of society, we propose to call it social morphology. Social morphology does not, moreover, have to limit itself to a descriptive analysis; it must also explain. It must look for the reasons why the population is massed at certain points rather than at others, why it is principally urban or principally rural, what are the causes which favor or impede the development of great cities, and so on. We can see that this special science itself has a multitude of problems with which to deal.

But parallel to the substratum of collective life, there is this life itself. Here we run across a distinction analogous to that which we observe in the other natural sciences. Alongside chemistry, which studies the way in which minerals are constituted, there is physics, the subject matter of which is the phenomena of all sorts for which the bodies thus constituted are the theater. In biology, while anatomy (also called morphology) analyzes the structure of living beings and the mode of composition of their tissues and organs, physiology studies the functions of these tissues and organs. In the same way, beside social morphology there is room for a social physiology which studies the vital manifestations of societies.

But social physiology is itself very complex and includes a multiplicity of individual sciences; for the social phenomena of the physiological order are themselves extremely varied.

First there are religious beliefs, practices, and institutions. Religion is, in effect, a social phenomenon, since it has always been a property of a group, namely, a church, and because in the great majority of cases the church and the political society are indistinct. Until very recent times, one was faithful to certain divinities by the very fact that one was the citizen of a certain state. In any case, dogmas and myths have always consisted in systems of beliefs common to an entire collectivity and obligatory for the members of that collectivity. It is the same way with rituals. The study of religion is, therefore, the domain of sociology; it constitutes the subject matter of the sociology of religion.

Moral ideas and mores form another category, distinct from the preceding. We shall see in another chapter how the rules of morality are social phenomena; they are the subject matter of the sociology of morality. There is no need to demonstrate the social character of legal institutions. They are to be studied by the sociology of law. This field is, moreover, closely related to the sociology of morality, for moral ideas are the spirit of the law. What constitutes the authority of a legal code is the moral idea which it incarnates and which it translates into definite formulations.

Finally, there are the economic institutions: institutions relating to the production of wealth (serfdom, tenant farming, corporate organization, production in factories, in mills, at home, and so on), institutions relating to exchange (commercial organization, markets, stock exchanges, and so on), institutions relating to distribution (rent, interest, salaries, and so on). They form the subject matter of economic sociology.

These are the principal branches of sociology. They are not, however, the only ones. Language, which in certain respects depends on organic conditions, is nevertheless a social phenomenon, for it is also the product of a group and it bears its stamp. Even language is, in general, one of the characteristic elements of the physiognomy of societies, and it is not without reason that the relatedness of languages is often used as a means of establishing the relatedness of peoples. There is, therefore, subject matter for a sociological study of language, which has, moreover, already begun. We can say as much of aesthetics, for, despite the fact that each artist (poet, orator, sculptor, painter, and so on) puts his own mark on the works that he creates, all those that are elaborated in the same social milieu and in the same period express in different forms a single ideal which is itself closely related to the temperament of the social groups to which they address themselves.

It is true that certain of these facts are already studied by disciplines long since established; notably, economic facts serve as the subject matter for the assembly of diverse research, analyses, and theories which together are designated as political economy. But just as we said above, political economy has remained to the present a hybrid study, intermediate between art and science; it is much less concerned with observing industrial and commercial life such as it is and has been in order to know it and determines its laws than with reconstructing this life as it should be. The economists have as yet only a quite weak sense that economic reality is imposed upon the observer like physical realities, that it is subject to the same necessity, and that, consequently, the science which studies it must be created in a quite speculative way before we undertake to reform it. What is more, they study facts, which are dealt with as if they formed an independent whole which is self-sufficient and self-explanatory. In reality, economic functions are social functions and are integrated with the other collective functions; they become inexplicable when they are violently removed from that context. Workers' wages depend not only on the relationships of supply and demand but upon certain moral conceptions. They rise or fall depending on the idea we create for ourselves of the individual. More examples could be cited. By becoming a branch of sociology, economic science will naturally be wrenched from its isolation at the same time that it will become more deeply impregnated with the idea of scientific determinism. As a consequence of thus taking its place in the system of the social sciences, it will not merely undergo a change of name; both the spirit which animates it and the methods which it practices will be transformed.

We see from this analysis how false is the view that sociology is but a very simple science which consists, as Comte thought, in a single problem. As of today, it is impossible for a sociologist to possess encyclopaedic knowledge of his science; but each scholar must attach himself to a special order of problems unless he wishes to be content with very general and vague views. These general views may have been useful when sociology was merely trying to explore the limits of its domain and to become aware of itself, but the discipline can no longer dally in such a fashion. This is not to say, however, that there is no place for a synthetic science which will manage to assemble the general conclusion which all these other specific sciences will reveal. As different as the various classes of social facts may be, they are, nonetheless, only species of the same genus; there is, therefore, reason to seek out what makes for the unity of the genus, what characterizes the social fact in abstracto, and whether there are very general laws of which the very diverse laws established by the special sciences are only particular forms. This is the object of general sociology, just as general biology has as its object to reveal the most general properties and laws of life. This is the philosophical part of the science. But since the worth of the synthesis depends on the worth of the analyses from which it results, the most urgent task of sociology is to advance this work of analysis.

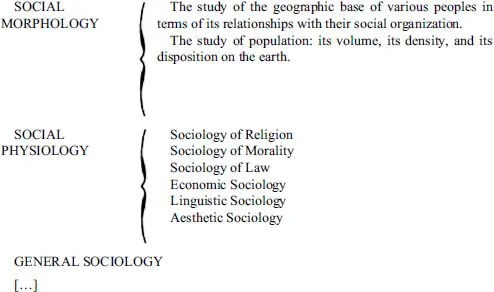

In summary, table 1 represents in a schematic way the principal divisions of sociology.

|

The principal problems of sociology consist in researching the way in which a political, legal, moral, economic, or religious institution, belief, and so on, was established, what causes gave rise to it, and to what useful ends it responds.

Reading 2 Review of Antonio Labriola, Essays Ys on the Materialist Terialist Conception of History

DOI: 10.4324/9780203337141-3

From: Emile Durkheim on Institutional Analysis, Edited and translated by Mark Traugott, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1978, pp. 127–130. Original publication in French as review of A.Labriola, Essais sur la conception matérial-iste de l'histoire, Revue philosophique, 44 (1897), pp. 645–65.

We think it a fertile idea that social life must be explained, not by the conception of it created by those who participate in it, but by profound causes which escape awareness; and we also think that these causes must principally be sought in the way in which associated individuals are grouped. It even seems to us that it is on this condition, and on this condition only, that history can become a science and that sociology can, consequently, exist. For, in order that collective representations be intelligible, they must arise from something and, since they cannot form a circle closed upon itself, the source from which they arise must be found outside themselves. Either the collective consciousness floats in a vacuum, a sort of unrepresentable absolute, or it is related to the rest of the world through the intermediary of a substratum on which it consequently depends. From another point of view, of what can this substratum be composed if not of the members of society as they are socially combined? We believe this proposition is self-evident. However, we see no reason to associate it, as the author does, with the socialist movement, of which it is totally independent. As for ourselves, we arrived at this proposition before we became acquainted with Marx, to whose influence we have in no way been subjected. This is because this conception is the logical extension of the entire historical and psychological movement of the last fifty years. For a long time past, historians have perceived that social evolution has causes with which the authors of historical events are unacquainted. It is under the influence of these ideas that they tend to deny or to restrict the role of great men and look to literary, legal, and other movements for the expression of a collective thought which no specific personality completely incarnates. At the same time and above all, individual psychology taught us that the individual’s consciousness very often merely reflects the underlying state of the organism and that the current of our representations is determined by causes of which the subject is unaware. It was then natural to extend this conception to collective psychology. But we are not able to perceive what part the sad class conflict which we are presently witnessing could have played in the elaboration or the development of this idea. No doubt, the idea ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Front Other

- Series Editor’s Foreword

- Preface to the Revised Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Introduction

- Part One— Sociology—Its Nature and Programme

- Part Two— Division of Labour, Crime and Punishment

- Part Three— Sociological Method

- Part Four— Suicide

- Part Five— Religion and Knowledge

- Part Six— Politics

- Part Seven— Education

- Bibliography of Durkheim’s Major Works