- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Working Girls investigates the thematic concerns of contemporary Hollywood cinema, and its ambivalent articulation of women as both active, and defined by sexual performance, asking whether new Hollywood cinema has responded to feminism and contemporary sexual identities.

Whether analysing the rise of films centred around female friendships, or the entrance of pop stars such as Whitney Houston and Madonna into film, Working Girls is an authoritative investigation of the presence of women both as film makers and actors in contemporary mainstream cinema.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Working Girls by Yvonne Tasker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film History & Criticism1

CROSS-DRESSING, ASPIRATION AND TRANSFORMATION

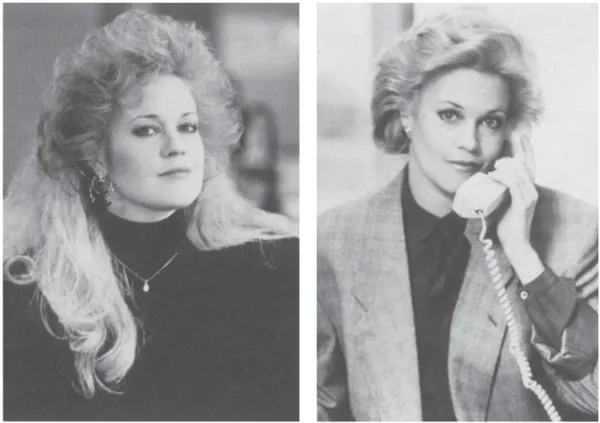

Cross-class dresser: Tess McGill (Melanie Griffith) in Working Girl

‘Just act like you belong’ Tess McGill tells Jack Trainer (Harrison Ford) in Mike Nichols’ Working Girl (1988) as they crash a ‘society’ wedding in pursuit of a business deal. Tess, played by Melanie Griffith, spends most of the film dressing up (in borrowed clothes) and acting as if she belongs. The ‘imposture’ both allows and necessitates her movement from white, working-class community to a middle management position in a New York company, though she clearly belongs absolutely in neither space. A critical and a commercial success, Working Girl is a sharp romantic comedy in which the heroine’s ability to manipulate costume and other aspects of her physical and social performance (hair, voice, mannerisms) reminds us that cross-dressing isn’t only an issue of gender, but also one of class. Or rather, the film underscores the extent to which these terms inform and give meaning to each other. For feminist criticism, the potential transgression of categories of gendered identity within and through cross-dressing holds an evident appeal, identified by Annette Kuhn in terms of a foregrounding of ‘the socially constructed nature of sexual difference’ such that ‘what appears natural…reveals itself as artifice’ (1985:49). Subtly suggestive of transgression, of the erosion of boundaries rather than crass opposition or binary logic, the appeal of cross-dressing imagery can be further situated within ‘queer theory’, with its characteristic delight in the gender-fuck and its passionate, political challenge to binary conceptions of identity.1 Movies such as Working Girl serve to reinforce Marjorie Garber’s thesis that the separation of gendered dress codes (and their transgression) from discourses of class, race, ethnicity and sexuality produces only a partial understanding of cross-dressing and its cultural significance (Garber 1992). Garber’s analysis of transvestism in the context of what such critics as Gail Ching-Liang Low (1989, 1996) have called ‘cultural cross-dressing’ (with T.E.Lawrence an exemplary figure) and her location of the theatrical cross-dresser in relation to traditions of, for example, minstrelsy, suggest the extent to which these different hierarchical discourses are inter-related. To reduce the analysis of cross-dressing to gender then, is to remove it from a complex historical relationship to constructions of race, class and sexuality and to particular lesbian, gay and trans-gender identities (drag, butch, femme). In turn, a narrow focus on the signifiers of gender neglects the extent to which narratives of gendered crossdressing often involve other kinds of transgression. Lola Young’s discussion of The Crying Game (1992) and of reviewers’ responses to it, for example, indicates how a discussion of race and nationality is sidestepped by the movie which ‘selfconsciously presents us with a disruption of sexual binarism whilst evading and failing to address racial binarisms’ (Kirkham and Thumin 1995:284). For Young, the attention paid to the ‘shock’ revelation that Dil (Jaye Davidson) is anatomically male was, for reviewers at least, at the cost of any discussion of the inter-racial relationship between Fergus (Stephen Rea) and Dil or the significance of the relationships between Dil and black British soldier Jody (Forest Whitaker), or Jody and Fergus in terms of either race or nationality.

For Christine Holmlund the butch clone and the femme lesbian, together with the passing black, are figures who are connected to ‘resistance and power’ through a refusal of the body as ‘truth’ (Cohan and Hark 1993:219). Though acutely aware of the ambivalence of these identities/performances, she contrasts the familiar anxious masquerade addressed by feminist critics with the potential for pleasure that is located in both the cinematic and the social performance of identities, a process that might in turn open up the contradictions of hierarchical systems of gender and race. Elsewhere Jane Gaines has written of ‘the radical possibilities of what might be called spectatorial cross-dressing’, addressing the mobility of identification that is invited by the cinema (Gaines and Herzog 1990:25). Popular texts offer both the powerful and the disempowered (though on quite different terms) a relatively risk-free identification with an other or series of others. The cinema produces fictionalised and fantasised versions of cultural identities. The cinematic spectator’s participation in a proffered transgression is quite different from the account of public identification offered by Marjorie Garber in her discussion of transvestite and transsexual experience, one in which:

The ‘men’s room’ problem is really a challenge to the way…cultural binarism is read…. The public restroom appears repeatedly in transvestite accounts of passing in part because it so directly posits the binarism of gender (choose either one door or the other) in apparently inflexible terms, and also (what is really part of the same point) because it marks a place of taboo.

(Garber 1992:14)

The risks that cross-dressers take and the decisions made here are surely different from those taken by an audience in breathless moments of identification which are nonetheless (relatively) safe. Thus the specificity of the lives of drag queens (and kings), of transvestites and transsexuals are quite distinct from the fantasy space of the cinema. Without producing an artificial distinction between two separate spaces, one termed ‘cinema’, the other the ‘social’, it is important to consider the specificity of cinematic cross-dressing. If it is a commonplace that entertainment is escapist, that the pleasures of popular cinema lie in being transported elsewhere, Richard Dyer (1977) has attempted to codify the spaces into which audiences are taken and the needs that this might address. In attempting to specify the stuff of which the Utopian aspects of popular cinema consists, Dyer stresses the experiential and the visceral aspects of ‘our’ response. Two recent movies involving drag are indicative here. Both To Wong Foo Thanks for Everything, Julie Newmar (1995) and The Birdcage (1996) work out their concerns around heterosexuality in terms of a fantasy opposition in which gay men and drag function as cyphers for some notion of ‘liberation’ set against stereotypical figures of repression (the small town, the Republican senator). To say that these movies are primarily about heterosexuality isn’t to either dismiss them or to exhaust them, but to look at them in terms of the fantasies that they speak to. What they share with most of the movies discussed in this chapter is a desire for, pleasure in and anxiety around transformation which is signified through costume.

Cross-dressing: Class, sexual and national identities

For audiences who are not explicitly addressed by the mainstream cinema, questions of interpretation and the nuances of performance become significant. In this context Andrea Weiss discusses a process of ‘reading in’ on the part of the lesbian spectator of a classical cinema that kept lesbian desire implicit. A grainy image of Marlene Dietrich in trademark top hat, white tie and tails, provides the cover image for Weiss’ 1992 study, Vampires and Violets: Lesbians in the Cinema. Dietrich’s cross-dressed image evokes the sexual ambiguity so central to her star persona. Weiss elaborates on the way in which Dietrich’s image could be constructed by spectators in relation to extra-textual rumour (rumours of Dietrich’s affairs with women). She explores in some detail the moment in Morocco when a tuxedo-clad Amy Jolly/Dietrich admires and then kisses a woman in the club where she works, before transferring her attention to the male. Weiss argues the moment is not simply recuperated, in part since the signification of costume as well as action and star image works against the construction of Dietrich within the codes of a manageable, heterosexual femininity. ‘Her costume’, notes Weiss ‘the tuxedo, is invested with power derived both from maleness and social class.’ In contrast to Tom Brown (Gary Cooper): ‘she is momentarily able to transcend both class and gender. Such an escape from societal limitations can be seductive for all viewers, male and female; for lesbian viewers it was an invitation to read into the image their own desire for transcendence’ (1992:35).

One of the most recognisable images of female-to-male cross-dressing in the world of entertainment is that of the female star body clothed in male evening dress: an image associated with cabaret stars such as Josephine Baker, and with stars of the ‘classic’ cinema such as Dietrich. This image is in turn reprised by Julie Andrews in the title role(s) of Blake Edwards cross-dressing musical, Victor Victoria (1982). The (northern) European associations of Dietrich’s star image are echoed and modified in the Parisian setting of Victor Victoria aligning this ‘aristocratic’ variant of the female-to-male cross-dresser with European decadence, constructed throughout in opposition to American directness and simplicity (or sometimes, it is implied, vulgarity). Julie Andrews as Victor is an impersonator in terms of gender, sexuality, class and nationality (masquerading as s/he is as a male, gay, East European aristocrat). Both Victor Victoria and the cabaret image of the eroticised, tuxedo-clad, female star on which it draws, generate meaning not only in relation to gender and sexuality, but in relation to class, ethnic and national identities. In her comments on Josephine Baker, star of the period within which Edwards’ movie is set, Garber notes how the occasional stage adoption of ‘white tie and tails’ was only one aspect of a thorough-going involvement with transvestism such that ‘[s]he seems to have found herself—or to have been found—almost constantly in contiguity with cross-dressing’. As a black American in Paris, and as ‘an occasion for the theatricalization of scandal and transgressiveness’ Baker orchestrated her image and her performances across different kinds of cross-dressing (1992:279). Class and gender are foregrounded when Sarah Collins (Whoopi Goldberg) dons a ritzy black tux (complete with country and western-style bow tie) for the final competition scenes in her made-for-cable, romantic comedy poolroom movie Kiss Shot (1989). Her tuxedo signifies more than the sense of formality about the occasion, marking her transgression in gender terms. Early on we learn that Sarah’s father has rejected her after the birth of her daughter. Yet if this grieves her, she remains a strong figure. In order to make money Sarah becomes a ‘poolroom hustler’, operating in opposition to a competitive male world throughout the movie. This transformation is actually a sort of rediscovery of the skills of her youth, a talent she ‘remembers’, following a strained visit to her distanced parents, whilst putting on a show for her daughter. The final match involves a battle of wills with her opponent, playboy/millionaire ex-boyfriend Kevin (Dorian Harewood). Sarah is playing to save her home for herself and her daughter, whereas he is playing just for the hell of it. The differences (class/wealth/gender) between them are both signalled and bridged through their (evening) dress as well as through the performance of the game itself.

If the Hollywood cinema has tended to sidestep any explicit address to class, it is nonetheless the case that the signifiers of class and of ‘race’ with which it is entwined are a constant presence, evident in a weight of unspoken assumptions and coded signs that are bound up with, but not reducible to gender and sexuality. Beverley Skeggs has argued that for working-class women, white and black, femininity can be understood as a costume or as a mode of performance that somehow does not fit. When put on it seems excessive, gaudy or parodic. For Skeggs this is no surprise since discourses of femininity have developed in and through the historical process of inscribing the difference of middle-class women in an industrialising society and a changing economy. Thus she argues that:

Working-class women were coded as inherently healthy, hardy and robust (whilst also paradoxically as a source of infection and disease) against the physical frailty of middle-class women. They were also involved in forms of labour that prevented femininity from ever being a possibility. For working-class women femininity was never a given (as was sexuality); they were not automatically positioned by it in the same way as middle and upper-class White women. Femininity was always something which did not designate them precisely. Working-class women—both Black and White—were coded as the sexual and deviant other against which femininity was defined.2

The extent to which femininities and masculinities are always already positions inscribed in terms of class and ‘race’ becomes apparent in a consideration of popular film images in relation to work, to labour and the bodies/costumes that this produces. Gender and class, that is, can be productively brought together around a notion of work, partially since labour is a defining term in both discourses. Manual labour defines a gendered class position just as much as genteel (indeed, gentile) femininity defines a classed gender role. Though the world of work is only rarely represented in popular cinema in terms of its mundanities (routine, repetition), an implicit or explicit reference to the status bestowed by work (or the lack of it) is nonetheless ever present, displaced into overdetermined signifiers of costume, speech or gesture. The populist rhetoric through which a classless notion of ‘the people’ has been constituted by American politicians and film-makers, has tended to imagine the proletariat as a male underclass. Male groups who are defined in terms of ‘race’ and ethnicity, such as Italian, Cuban or African-Americans, and situated literally on the street have come to signify ‘class’. Sometimes suffused with nostalgia, their separateness is represented in terms of ethnically understood custom and ritual rather than work (labour) or, more precisely work as ritual in the most stereotypical form of gangster groupings with their elaborate and exclusive membership and rules of behaviour.3 For women, as we’ve seen, entry into this space tends to involve a sexualised form of criminality: signified in the figure of the ‘streetwalker’. If women tend to be marginalised within both gangster/gangsta narratives, the importance of dressing the part, of a physical, verbal and costumed performance within the context of the male group, remains central.

The successful horror hybrid The Silence of the Lambs foregrounds processes of transformation, offering a parallel between its two central cross-dressers, the serial killer Buffalo Bill who is producing a grotesque body suit from the flayed flesh of his female victims, and Clarice Starling (played by Jodie Foster), the cross-class cross-dresser who pursues him. Two types of cross-dressing: one extolled in a heroic character, the other pathologised in the monstrous figure of the killer. Starling’s transformation, her ascent through the ranks of the FBI, is predicated on her discovery of Bill’s predilection. Ultimately sidelined within the institution of law enforcement, left hanging on the phone by boss and mentor Jack Crawford, Starling’s (intuitive) recognition of another cross-dresser leads her to the prize (advancement). As Elizabeth Young notes, the film’s ‘theorizing of gender as costume runs parallel to its recognition that class can be transformed by clothing: thus Clarice’s self-fashioning materially represents her class ascension to professional career woman’ (1991:26). In their first interview, Clarice’s sinister mentor, psychoanalyst and serial killer Hannibal Lecter, discerns immediately the history behind her dress, the contradiction between her ‘good bag’ and her ‘cheap shoes’. Lecter taunts her with his cynical rendition of her personal history: an attempt to shed an embarrassing accent, to adopt the guise of the professional working woman:

You’re so ambitious aren’t you? You know what you look like to me, with your good bag and your cheap shoes? You look like a rube, a wellscrubbed, hustling rube with a little taste. Good nutrition’s given you some length of bone, but you’re not more than one generation away from poor white trash—are you Agent Starling? And that accent you’ve tried so desperately to shed—pure West Virginia. What is your father dear—is he a coal miner? Does he stink of the land? And oh how quickly the boys found you—all those tedious, sticky fumblings in the back seats of cars, while you could only dream of getting out, getting anywhere, getting all the way to the F-B-I?

In both The Silence of the Lambs and the earlier Manhunter (1986), Lecter’s malevolent professional abilities are defined in terms of an intuition that allows him to identify and manipulate the weaknesses of his captors. For Starling this is her class/ethnic location, and the desire to escape it which makes it intolerable.

There is a particularity here which speaks of class and status in localised ways as well as the specificity of West Virginia and what it may mean for an international as well as a domestic audience (poor white trash). That origin provides a way of signalling more than poverty, suggesting the backward values of an uneducated people. More than an observation made in passing, the above exchange is marked as a moment of significance within the film: the music swells under Lecter’s (Anthony Hopkins) ‘actorly’ delivery, his face intercut with Starling’s so as to render the pain of recognition clear. Starling’s ability to identify with ambition, and with the desire to be something other than what one is, ultimately enables her to find the killer. Yet she is different from the self-destructive, emphathising hero of Thomas Harris’ novel Red Dragon and Michael Mann’s Manhunter (also tormented by Lecter’s insights) since Clarice Starling is a cross-class cross-dresser. Her cross-dressing is not played for comedy. It is subtle, nuanced: one part of her transformation, and of the broader ‘rites-of-passage’ narrative that the movie enacts. Her transformation through costume and through work is suggestive. For women in the cinema, cross-dressing is almost always about status—something which is doubly apparent when we understand femininity itself as a class position, one from which many women are excluded. In this context ambition, like desire or need, is unequivocally inscribed as ‘unfeminine’.

Genres of cross-dressing

In her analysis of gendered cross-dressing narratives, which she terms ‘films involving sexual disguise’, Annette Kuhn suggests two broad generic locations: the musical comedy and the thriller. In these instances, she argues, not only does gendered cross-dressing become a source of comedy or of horror, but generic conventions offer particular ways in which to naturalise (or explain away) the activity of cross-dressing itself. Within the musical comedy, Kuhn suggests that cross-dressing is rendered plausible in terms of ‘the work ethic and the necessity for economic survival’, whilst within the thriller cross-dressing ‘is naturalised through discourses on sexual deviance, psychopathology and criminality’ (1985:59). Though this does not provide an inclusive definition of cross-dressing as it is used here, excluding screwball and other non-musical comedies (Working Girl, Mrs Doubtfire), Westerns (The Ballad of Little Jo) and romantic dramas (Up Close and Personal), Kuhn’s observation can be usefully adapted to identify two distinct narrative dynamics deployed in films which articulate cross-dressing across categories of gender, ‘race’ and class. The first is to do with transformation, whilst the second concerns a desire for knowledge. If the need to work operates as an ‘excuse’ for gendered cross-dressing in movies such as Victor Victoria, in which Andrews’ character faces starvation or prostitution, it is also precisely cross-dressing which facilitates a movement from a context of privation to one in which needs are (provisionally) satisfied. Comedies and musicals offer generic pleasures of excess, spectacle and the possibility of change/escape, a context within which an imagery of cross-dressing articulates the precarious persistence of sexual and racial binaries.

Straight or gay, films of male to female cross-dressing (Mrs Doubtfire, To Wong Foo Thanks for Everything, Julie Newmar, The Birdcage), and of working-class women cross-class dressing (Working Girl, Pretty Woman) share a delight in sequences of transformation, enacting visually as well as narratively a process of ‘becoming something other’ that is conducted through/over t...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION: BAD GIRLS AND WORKING GIRLS IN THE ‘NEW HOLLYWOOD’

- 1: CROSS-DRESSING, ASPIRATION AND TRANSFORMATION

- 2: COWGIRL TALES

- 3: ACTION WOMEN: MUSCLES, MOTHERS AND OTHERS

- 4: INVESTIGATING WOMEN: WORK, CRIMINALITY AND SEXUALITY

- 5: ‘NEW HOLLYWOOD’, NEW FILM NOIR AND THE FEMME FATALE

- 6: FEMALE FRIENDSHIP: MELODRAMA, ROMANCE, FEMINISM

- 7: ACTING FUNNY: COMEDY AND AUTHORITY

- 8: MUSIC, VIDEO, CINEMA: SINGERS AND MOVIE STARS

- 9: PERFORMERS AND PRODUCERS

- NOTES

- FILMOGRAPHY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY