- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hiphop Literacies

About this book

Hiphop Literacies is an exploration of the rhetorical, language and literacy practices of African Americans, with a focus on the Hiphop generation. Richardson analyses the lyrics and discourse of Hiphop, explodes myths and stereotypes about Black culture and language and shows how Hiphop language is a global ambassador of the English language and American culture.

Richardson examines African American Hiphop in secondary oral contexts such as rap music, song lyrics, electronic and digital media, oral performances and cinema and brings together issues and concepts that are explored in the disciplines of folklore, ethnomusicology, sociolinguistics, discourse studies and New Literacies Studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hiphop Literacies by Elaine Richardson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

BLACK/FOLK/DISCOURSEZ

OutKast and "The Whole World"

Although rap music and Hiphop elements have been adopted and adapted by many cultures around the world,1 this chapter, indeed this book, focuses on Hiphop discourse as a subgenre and discourse system within the universe of Black discourse which includes African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and African American Music (AAM) among other diasporic expressions. The central question that guides this analysis is: How do rappers display, on the one hand, an orientation to their situated, public role as performing products, and, on the other, that their performance is connected to discourses of authenticity and resistance? An aspect of my project is to shed light on the connection between the discursive (dis)invention of identity and the (dis)invention of language. In attempting to do this, I bring together issues and concepts that are explored in disciplines of folklore, ethnomusicology, sociolinguistics, and discourse studies. I begin by defining African American Vernacular Discourse (AAVD) as a genre system within Black diasporic discourses and in a selected sample of its various idioms, with a brief overview of the sociocultural, political, and economic contexts for selected genres. I then turn to an exploration of the function and use of Hiphop/rap discourse, using the example of a rap performance by the African American Southern rap group OutKast. The analysis is informed by principles of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). Discourse is central to social practices and questions of power and can benefit from CDA which foregrounds the hierarchy of social structure and social inequality, unequal power arrangements. CDA illuminates the expression of such in its examination of the multiple and contradictory nature of signs and discourses. The semiosis of symbols, signs, and visual imagery are also analyzed as part of discourse as they too reflect these social practices. (Halliday, 1978; Fairclough and Chouliaraki, 1999; Sebeok, 2001; van Dijk, 2001)

Black and African American Vernacular Discourses

The concept and practice of Black discourse refers to the collective consciousness and expression of people of Black African descent. This consciousness reflects (unconscious and conscious) ancestral and everyday knowledge. Broadly speaking, the designation the Diaspora of Black Discourse(s) allows us to group a range of African, Neo-African, and Afro-American language varieties, expressive forms, and linguistic ideologies for comparative analysis of specific historical, political, sociocultural, and sociolinguistic features. Via slavery, colonization, neo-imperialism, migration, wars, global technological processes, and diasporic crossing, Continental Africans and their descendants participate in the (dis)invention and global flow of Black discourse. Black discourses are a direct result of African–European contact on the shores of West Africa and in what became the New World. For example, the use of English by Africans originated for purposes of negotiation and trade, initiated by Europeans. In 1554, the Englishman William Towerson took five Africans from a British territory in West Africa known as the Gold Coast to England, to learn English, to become interpreters. Three of these Africans returned to the Gold Coast in 1557. Thus, 1557 is accepted as the beginning of the African use of English (Dalby, 1970). We could say that Africans were already at a disadvantage because they were in the position of learning a language of trade and commerce while having no familiarity with its total system. In a language learning situation like this one, critical and multiple consciousnesses are built into the language acquisition process. In other words, a group makes the new language fit, to the extent possible, its epistemological, ontological, and cosmological system. This is how we can say that there are uniquely Black versions of English, French, Dutch, and Portuguese, for which Robert Williams and his associates coined "Ebonics." Other scholars, Africologists, consider all forms of Ebonics as new African languages, rather than Black versions of European languages.2 Rickford and Rickford (2000) offer a balanced explanation, pointing out African, European, and creole sources for various language patterns in US Ebonics, for example. Most scholars of language agree that when Africans and Europeans "met," their languages mingled to create new African- and European-influenced language systems. One thing is for sure, people of African descent have evolved and contributed Ebonic and Pan African discourses to the world wherever they have found themselves on the continent and in the diaspora, bringing with them that flava and spirit of survival. Dalby (1970:4) gives a useful outline of this phenomenon:

"Black" enables us to group together a wide range of speech forms, on both sides of the Atlantic, in which a largely European vocabulary is coupled with grammatical and phonological features reminiscent of West African languages: … The clearest examples of ["Black Atlantic"] languages are what may be termed "creoles" or "creolized languages," in each of which the divergence from the original European language has been so great that one may consider a new language to have come into being, no longer inter-intelligible with its European counterpart.

Examples of these creole languages are found on both sides of the Atlantic, especially in the Caribbean and along the West African coast. At the other end of the scale of Black Atlantic languages are the dialectal variants of European languges which, although directly identifiable with Black speakers, have remained largely intelligible to White speakers of the same languages, [African] American English and Jamaican English (as opposed to Jamaican creole) may be cited as examples, in which the structural influence of West African languages—although very much reduced—may nevertheless be clearly traced.3

Although it is often helpful to understand language from a structural-grammatical perspective, this view of language can obscure the fact that it is history, culture, and lived experience. As stated by Brathwaite (1993:266) in his discussion of the "History of the Voice": "It may be in English [for example], but often it is in an English which is like a howl, or a shout, or a machine-gun, or the wind, or a wave. It is also like the Blues. And sometimes it is English and African at the same time." This is why I am so interested in Black language as discourse. Black discourses are not fixed and static. They are dynamic and reflexive systems of "behaving, interacting, valuing, thinking, believing, speaking, and often reading and writing that are accepted as instantiations of particular roles … by specific groups of … people … [Black] Discourses are ways of being ['an African descendant']. They are 'ways of being in the world'; they are 'forms of life'. They are, thus, always and everywhere social and products of social histories." (Adapted from Gee, 1996: viii) It is

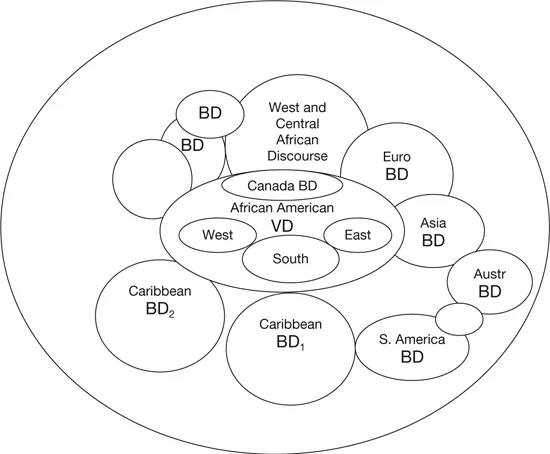

Figure 1.1 Diaspora(s) of Black discourse

important to draw attention to the inclusion of reading and writing or Africanized literacy in the definition of Black discourse, as literacy is informed by discourse and is an ideologically charged social construction. (Richardson, 2003)

In the North American context, we can identify AAVDs by manifestations of their many signature themes and forms. They include the various sociocultural forms and institutions developed by African Americans to express their distinctive existence. From this perspective, there are African American ways of being and communicating that derive from particular histories, geographies, and social locations. Some of these ways of being were developed during slavery and influenced by two crucial factors: the demand from dominant Whites that all manner of behavior and communication of African people display their compliance with domination and supposed inferiority; and African people's resistance to this demand "through the use of existing African [communication] systems of indi-rectness." (Morgan, 2002: 24) As Morgan explains, "indirectness includes an analysis of discourses of power … Once the phenomenology of indirectness operated both within white supremacist encounters and African American culture and social encounters, interactions, words or phrases could have contradictory or multiple meanings beyond traditional English interpretations." The grammatical and pronunciation patterns of AAVE are often analyzed as apart from its ideological-discursive aspects for purposes of structural analysis. In this project, the emphasis is on AAVE and AAM as part and parcel of AAVD, as all of these are inextricably linked systems and are a direct result of African–European contact on the shores of West Africa and in what became the New World. In the present work, AAVE includes the broad repertoire of themes and cultural practices as well as narrowly conceived verbal surface features used by many historic and contemporary African Americans, which indicate an alternate worldview. In other words, AAVE represents the totality of vernacular expression. AAVE should be understood as African American survival culture. On the level of language, although the majority of the words are English in origin, their meanings are historically and contextually situated relevant to the experiences of African Americans. Further, a point that is often overlooked is that there is a Standard AAVE. Scholars of AAVE argue for an expanded conception of it, whereby many speakers command a wide range of forms on the continuum from more creole-like to more standardized forms. In this sense, "an educated, middle-class [B]lack person may express his or her identification with African American culture, free of the stigma attached to nonstandard speech [/grammar]" (DeBose, 1992: 159)4

To put it another way, African American Standard and Vernacular discourses are in dialectical relation and are in dialogic relation to other diasporic discourses, American discourses, as well as other global discourses. By extending the definition of African American language usage beyond (surface level) syntax, phonology, and vocabulary, etc. into (deep-level) speech acts, nonverbal behavior, and cultural production, the role of language as a major influence in reality construction and symbolic action is emphasized. The multiethnicity of symbols is more apparent in this view.5

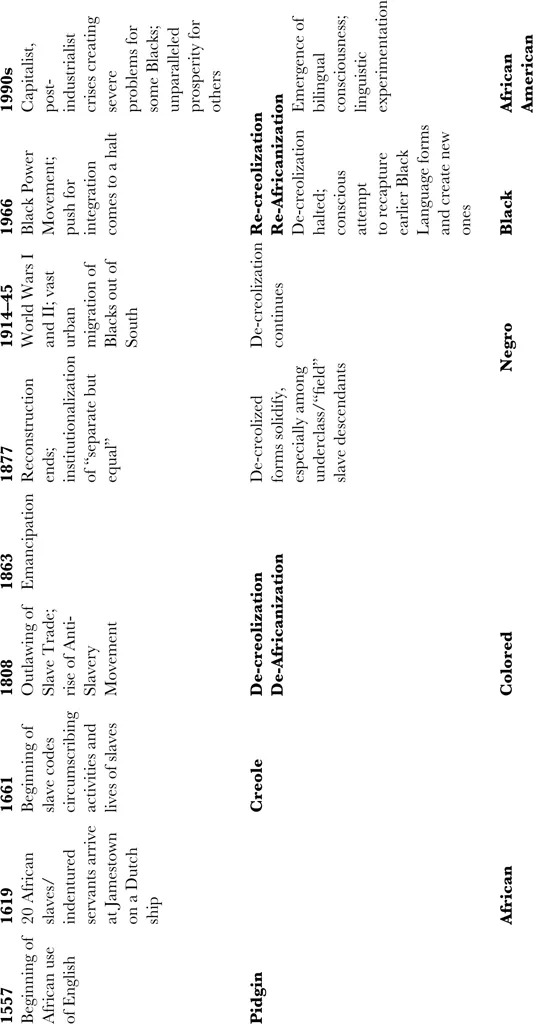

Figure 1.2 Smitherman's model of U.S. Ebonics and the Black experience

Everyday experiences of African Americans require heightened attention to language use and ritual performance. Uniquely Black usages of language occur in most domains of life, including Street Life, Church Life, Politics and others. Thus, theorizing about African American language use requires emphasis on rhetorical context, the language users, their history, values, sociocultural, political, and economic position. (Debose, 2001) Smitherman's model of U.S. Ebonics and the Black Experience (1987/2000: 36) is helpful in visualizing, for example, the complex context that shapes African Americans' use of language in the New World and what became the United States from 1557 through the 1990s.

Not only does Smitherman's model allow for the linguistic continuum concept, wherein speakers can potentially move up or down different linguistic zones, one end of which is closer to a European language/culture and the other of which is comprised of a creole form characterized by more African-derived features (Alleyne, 1980; Rickford, 1987), her model also emphasizes the social world which influences how language is interpreted, defined, conceived, performed, with other expressions and symbols and juxtaposed against such to (re)interpret reality. One must be mindful that the horizontal or vertical conceptualization of the continuum can subordinate the heteroglossic and layered nature of discourse. In other words, the linguistic continuum cannot be separated from the sociocultural continuum. From the enslavement era through the present, African American beliefs and practices are informed by those of various African cultures and respond to, borrow from, and negotiate the practices of the dominant culture. The social locations of the performer and the audience determine how meaning is interpreted. Social actors can manipulate certain elements within the continuum in line with their rhetorical goals. When we think of African American language as inseparable from African American discourse, we keep in mind the cultural frames, performance traditions, idioms, etc. that inform the expressive forms, the senses and sounds of real people conveying meaning to each other within the context of a shared (or not, depending on one's social location) set of assumptions about the nature of the world. Portia Maultsby's (1991: 186) representation of the development of African American music is helpful.

Residing on the uppermost part of the Black Diaspora discourse continua are diverse West and Central African beliefs and practices/West and Central African Communication Patterns/and West and Central African Musical Roots. In general, across each of these domains respectively, we can identify an African ethos that extended to the so-called New World context, beginning in the seventeenth century, encompassing both sacred and secular speech, expressions, and musical idioms. Though Smitherman (2000: 1) is focusing on American Black Talk, her sentiments relate on the level of the African Diaspora. She writes: "Black Talk crosses boundaries of age, gender, region, religion, and social class because it all comes from the same source: the [Black] Experience and the [African] oral tradition embedded i...

Table of contents

- LITERACIES

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PREFACE

- 1 BLACK/FOLK/DISCOURSEZ

- 2 CROSSCULTURAL VIBRATIONS

- 3 YOUNG WOMEN AND CRITICAL HIPHOP LITERACIES

- 4 RIDE OR DIE B, JEZEBEL, LIL’ KIM OR KIMBERLY JONES AND AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN’S LANGUAGE AND LITERACY PRACTICES

- 5 “YO MEIN RAP IS PHAT WIE DEINE MAMA”

- 6 HIPHOP AND VIDEO GAMES

- APPENDIX

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

- INDEX