![]()

Chapter 1

Social policy, social work and social care

OUTLINE

This chapter will:

• | discuss the development of social policy, its definition and its relationship with social work |

• | examine the relationship between social work and the state |

• | outline the main areas of social work |

• | describe the value dilemmas involved in social work practice. |

From social administration to social policy

Social policy has been closely linked with social work since the first social work students were trained at the London School of Economics at the beginning of the twentieth century. Social policy was presented as an administrative and organizational discipline concerned with giving students the knowledge to manage welfare efficiently, teaching students how to be social administrators so that they could better operate the emerging welfare services. Debate about how appropriate the current welfare system was came second to the task of improving existing welfare provision, the principles of which were taken for granted. To talk of social policy at this stage would be misleading; the subject area was social administration.

Throughout the early part of the twentieth century, research into welfare focused on how poverty was implicated in a range of social problems. Researchers measured need in order to provide the technical information upon which policy-makers could act. Questions about how need should be defined or responded to were not the stuff of social administration. This approach reached its zenith during and after the Second World War when governments commissioned social research to plan the war effort and subsequently construct the post-war Welfare State.

From 1945 to the early 1970s, social administration operated within a social and political consensus that the state should take considerable responsibility for the welfare of its citizens. It developed for the most part within narrow policy parameters, which accepted rather than questioned the nature of this compromise and the role that welfare played within it. This compromise has often been referred to as the ‘post-war consensus’ or ‘settlement’. The ruling sections of the major political parties, the civil service, representatives of industry and the trade unions generally agreed that the continued expansion of the Welfare State was in all their interests. The dominant issue for the discipline of social administration was how to develop the Welfare State by refining government policy within this broad agreement.

By the early 1970s, the consensus around the Welfare State and the role of social administration within it began to fragment. Critics from a variety of ideological positions began to doubt the basic assumptions upon which the Welfare State and social administration were based. Marxist, New Right and feminist writers, for example, began to unpick the policies and major assumptions upon which the post-war settlement had nourished the expansion of the state into welfare. As a result, a more critical and sociological conception of the study of welfare developed – social policy widened the question of welfare beyond the confining limits of social administration.

What is social policy?

Social policy studies not only the organization and delivery of state welfare services, but also how well-being can be promoted within society generally. Well-being may be achieved through the satisfaction of individuals’ socially defined needs. Although adequacy of food, shelter and clothing may seem to be an unambiguous measure of need, these needs are expressed differently by people from different cultures and societies. If we take into account people’s psychological and emotional development, the issue becomes more complex and presents social policy with new challenges. If, for example, parents cannot leave their children to play safely in the street for fear of a car accident or abduction, their sense of well-being is affected. These questions require us to be clear at what level and to what extent the Welfare State can and should satisfy need.

At one level we can take a more inclusive view and include differences of culture, taste and the so-called higher emotional and psychological needs; or we can use a restrictive approach, which keeps the satisfaction of needs at a basic level, usually focusing on food, shelter and clothing. These questions move beyond the academic when we consider how far the state should satisfy the needs of specific individuals. How much, for example, should the state allocate in social security benefits to meet the needs of those unable to maintain themselves? Should the present basic level of income support be increased to meet the wider social and psychological needs of claimants? How much recognition of different needs between claimants should there be? Should the extra costs incurred in being a single parent/carer or a person with a physical disability be taken into account? By limiting benefit payment for these extra costs, those affected face significant barriers to participate fully in society.

Social policy does not content itself only with academic considerations; it also aims to improve social conditions. To do so it has to consider appropriate social action; inevitably value judgements have to be made in choosing between one course of action over another. This presents a dilemma for social policy between analysis and practice; as Erskine (1997, p. 14) suggests, ‘analysis requires scepticism while practice requires conviction’.

Issues for social policy

In understanding the concept of well-being, social policy uses the methods of a number of social science disciplines to engage with social problems in a rigorous and scientific way. Deciding what action to take means choosing between alternatives and taking sides. This raises dilemmas ‘which social science cannot resolve’ (Erskine 1997, p. 7). Social science can inform and guide us by clarifying the reasons for choice, but it cannot make the choice for us.

Social policy has to consider:

• | well-being – not just as a product of government action, but as a result of social factors. |

It is impossible to assess the contribution of people caring for others if our focus is purely on the caring services provided by the state. The majority of care in society is delivered informally, mostly by women, and makes an enormous contribution to the overall level of well-being in society.

Social policy therefore considers:

• | who provides welfare, which groups benefit from it, and, particularly, how access is denied to some groups. |

The informal care provided by women comes at a cost of forgone careers, time, emotional effort and so on. This unrecognized labour benefits government and saves the Welfare State considerable expense.

• | the impact of welfare on the overall distribution of power and wealth in society. |

Providing unpaid and unrecognized care restricts women to the private sphere of the family, enabling men to achieve recognition and power in the public sphere of work. This increases women’s dependence upon men, and effectively limits their opportunity to acquire income and wealth independently.

Social difference

In recent years, social policy has begun to study the concept of social difference, i.e. how the social location of the providers and users of services affects their experience of welfare. It looks at those groups who have been marginalized by society, and studies their everyday experience of welfare. It attempts to link their personal and often private experiences with the public face of social policy. Recently, marginalized groups, such as people with disabilities, single parents and people from ethnic minorities, have demanded that their voice be heard in the policy-making process. As a result, their demands are making some impact on the policy-making process and the delivery of welfare. For many writers, the concept of social difference has become a key theme in the analysis of social policy. Chapter 3 looks more closely at these issues.

Social work and social policy

Social work and social policy share a commitment to social change. Social work addresses issues of:

• | individual rights to welfare |

• | the rights of the individual and the expectations of society |

• | challenging inequality and oppression experienced by users |

• | justice in social policy. |

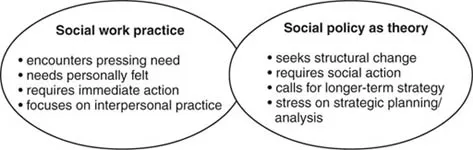

Both social work and social policy have experienced radical change. Social policy has broadened its approach to take into account the diversity of people’s experiences and the essentially contested nature of the Welfare State. Social work, in developing anti-discriminatory approaches, seeks to put this theoretical knowledge of difference into practice. This demands an approach that understands people’s personal problems within a broader social context and uses this knowledge to effect change both for individuals and their social environment. Figure 1.1 shows the interface between social work and social policy.

Figure 1.1 Social work and social policy

For students approaching social work, social policy explains both the social circumstances of the users of social work services, and the social work organizations themselves. Social policy can therefore explain how social work as a service is:

• | produced – through a mixed economy of care |

• | consumed – with differences in how social work and social care services are experienced and accessed by users |

• | distributed – with unequal distribution of services between different classes, age groupings or ethnic groups. |

Case study

Mr Amarnath ...