![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Linking ecosystem services with environmental justice

Thomas Sikor

Introduction

Radical critics assert that ecosystem services-based governance interventions tend to sustain or even aggravate injustices in environmental management in the Global South. The governance interventions continue or deepen the exclusion of local people from natural resources important to their livelihoods. In the worst case, the critics find, interventions such as Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) can lead to the monetization of indigenous economies or local people’s dispossession in so-called ‘green grabs’.

In contrast, proponents of ecosystem services argue that the new-style governance interventions have the potential to make environmental management in the Global South more just. They suggest that interventions such as PES and Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) can produce so-called ‘win-win’ solutions: they can help to conserve important ecosystem services – justice to nature – and simultaneously alleviate poverty – intragenerational justice. The advantages of the new-style interventions are clear, they point out, if we compare them to past approaches, under which local people were excluded from vital resources without any compensation.

The debate between critics and proponents of ecosystem services demonstrates two key points of departure for this book. First, justice matters to people; people including villagers, practitioners, policy-makers, government officials and scholars alike. Even if few of them phrase their positions explicitly in the language of justice, arguments about ecosystem services provisioning, biodiversity conservation, poverty alleviation and livelihood improvement are saturated with ideas of justice. Second, people tend to assert different notions of justice. As much as justice permeates people’s views on environmental management, the particular notions of justice they apply often appear incompatible. For example, critics may deplore cash payments made for tree planting as unjust for undermining customary practices of environmental stewardship and intergenerational responsibility. At the same time, proponents may applaud the payments as just for their contribution to poverty alleviation.

Justice matters for environmental management because interventions almost always affect the distribution of benefits and responsibilities, different people’s participation in decision making or the recognition of their particular identities and histories. These justice-relevant outcomes in turn influence people’s reaction to governance interventions, making justice an integral component of environmental management. For example, an afforestation project involves decisions about who should plant trees and who should be paid how much for planting trees. These decisions tend to reflect the influence of some people, such as male landowners, but not afford similar opportunities of participation to others, for example landless women. Consequently, male landowners and landless women are likely to respond to the afforestation initiative in different ways and analysts will evaluate it differently depending on the notions of justice they apply.

The book develops this interpretation of justice on the basis of recent environmental justice research. It demonstrates how particular governance interventions based on the Ecosystem Services Framework, such as PES, REDD+ and tourism revenue-sharing around protected areas, work out to be just in some ways and unjust in others. Interventions tend to open up opportunities for enhancing environmental justice according to some perspectives yet also reveal design features that cause them to generate injustices from other vantage points. The book traces this tendency of ecosystem services-based governance interventions to generate justices and injustices back to particular features of the Ecosystem Services Framework.

The primary aim of the book is to open up new middle ground in debates on environmental management and environmental justice. Conceptually, the book seeks to reconcile the positions of critics and proponents of ecosystem services by suggesting that both should think of environmental management in the Global South as creating justices and injustices simultaneously. Any particular intervention is likely to be just for some people and unjust for others, and just in some ways and unjust in others. On a more practical note, the book intends to open up a new platform for dialogue between critics and proponents of ecosystem services. Once both camps recognize the influence of plural notions of justice, they can start to enable and engage with each other in a dialogue on a level playing field. More importantly, once critics and proponents recognize the significance of justice as a motivation – and not simply a constraint – they can begin to develop approaches which tap the power of justice as a driver of environmental management.

To prepare the analyses presented in the remainder of the book I develop the key concepts shared across all chapters in this introduction. I begin with brief reviews of the Ecosystem Services Framework and recent environmental justice research. I subsequently lay out key concepts for application to ecosystem services and conclude with a brief overview of the book.

Brief recap: Ecosystem services

The Ecosystem Services Framework provides a novel conceptualization of nature–society relations. It is used in several variations and the one introduced here stems from the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). The MEA definition has become the most influential one and shares the key concepts with other formulations.

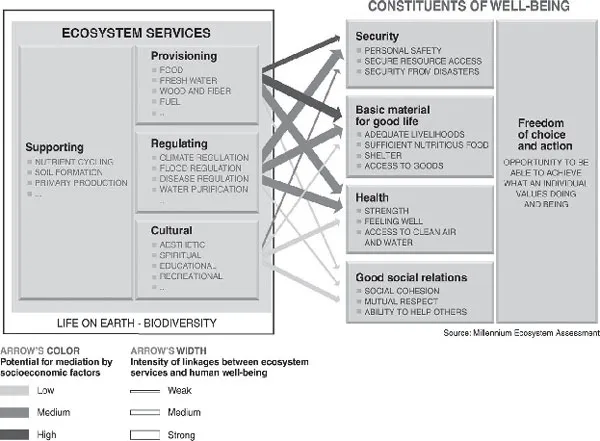

Ecosystem services are at the core of this framework (see Figure 1.1). They are defined as ‘the benefits people obtain from ecosystems’ (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005, v). Ecosystem services include four types:

Figure 1.1 Linkages between ecosystem services and human well-being

provisioning services such as food, water and fibre, i.e. services directly consumed or used by people;

regulating services that affect climate, floods, disease, wastes and water quality, i.e. services that provide the environment in which people live;

cultural services generating recreational, aesthetic and spiritual benefits to society;

supporting services such as soil formation, photosynthesis and nutrient cycling.

Figure 1.1 indicates how ecosystem services are seen as intimately tied to human well-being within the MEA framework. Human well-being is broadly conceived to have multiple components, including not only the material conditions required for sustained livelihoods such as food and shelter, and for a healthy life such as clean air and water. Well-being also attends to good social relations such as social cohesion and human security, the latter includes protection from natural and human-made disasters among other threats to human security. Additionally, the concept comprises freedom of choice and action, which is understood to be influenced by other components of well-being and constitutes a precondition for achieving other aspects of well-being.

The key message emanating from the Ecosystem Services Framework is that ‘[t]he human species…is fundamentally dependent on the flow of ecosystem services’ (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005, v). In the framework, nature is a stock that provides a flow of services to people in contrast to other conceptualizations of nature as complex systems (Norgaard, 2010). This has two fundamental implications for the relations between people and nature. First, nature not only contributes to human well-being, but the benefits provided by nature are a critical precondition for a good life. Second, concerns over well-being become the primary reason why people should protect ecosystems or manage them in a sustainable manner. The task of weighting the different services provided by ecosystems to people becomes the critical challenge in environmental management, as illustrated by the weightings given to the arrows in Figure 1.1.

The emphasis on services is a distinctive feature of the conceptualization of nature–society relations in the framework (Lele et al., forthcoming). The Ecosystem Services Framework downplays the significance of intrinsic values, i.e. the value of nature in and for itself. For example, biodiversity no longer figures as something that people have to conserve irrespective of its utility for people. Nature turns into services. Aspects of nature that would be considered to possess intrinsic values in other conceptualizations become cultural services, which may generate ample benefits to people yet may nonetheless be traded off against other, more beneficial services. Similarly, biological and other internal ecosystem processes are categorized as supporting services, services that once again have no right of existence beyond their ultimate contributions to human well-being.

The framework acknowledges the possibility that ecosystems cannot provide all services simultaneously, at all times and everywhere. Management interventions typically encounter trade-offs between competing services. For a single type of ecosystem service, there are trade-offs ‘in space’ and ‘in time’ (Rodríguez et al., 2006). Spatial trade-offs arise when the use of a service in one location impinges on its potential use in another location (e.g. upstream water use limits downstream water availability). Temporal trade-offs occur when the use of a service at one point in time diminishes its availability for use at other times. In addition, multiple kinds of ecosystem services may be interconnected, giving rise to another type of trade-off, when the use of one type of service influences the use of other, connected kinds of services. For example, wood harvests upstream may affect the overall volume, seasonal flow or quality of water downstream.

Ecosystem services has not only been an influential concept but also it is associated with fundamental changes in the governance interventions used for environmental management. The practice of environmental management has gradually shifted away from protected areas and other interventions relying on regulations made by national government, international bodies or local user groups. These are being replaced by interventions that in the spirit of the Ecosystem Services Framework seek to link the providers and users of ecosystem services more directly.

PES schemes are the paradigm type of intervention compatible with the Ecosystem Services Framework, even though many have emerged before the global ascendance of the latter. Such schemes use payments to align the interests of resource managers with (actual or potential) beneficiaries of their management practices. For example, downstream people pay fees for the use of water, which are then employed to pay upstream people for land management practices considered to enhance hydrological services. This is the rationale underlying the world’s largest PES scheme, the Sloping Land Conversion Program in China, under which the Chinese government pays farmers to plant trees in upper watersheds (Bennett, 2008). Similar rationales drive the development of PES schemes for forest, agricultural, marine and coastal ecosystems around the globe.

However, it is also important to recognize the difference between the theoretical justifications and actual practice as well as variation in real-world PES schemes. In theory, payments are conditional on performance, i.e. actual provision of the ecosystem service(s) of interest. They are also conceived as voluntary transactions between the suppliers of ecosystem services and their buyers (Wunder, 2005). However, the practice of PES remains different because conditionality and direct transactions are hard to achieve (Muradian et al., 2010). Many PES schemes rely on proxy indicators for performance, such as application of specific land management practices, because the actual ecosystem service(s) of interest cannot be observed directly. Many operate through proxy institutions, such as government programmes or NGO projects, instead of as direct transactions between the beneficiaries and providers of ecosystem services.

REDD+ represents, arguably, the most ambitious initiative to date to implement the ecosystem services approach (Angelsen et al., 2012). The particular ecosystem service at the centre of REDD+ is the carbon stored in woody biomass and soil, emitted when forests decompose and absorbed when forests grow. REDD+ seeks to tap the potential of tropical forest management to contribute to the mitigation of climate change, utilizing financial transfers to tropical countries to entice forest management that avoids carbon losses and increases carbon stocks. Tropical countries are required in return to reduce the use of provisioning services from forests, that is, reduce timber logging or limit the conversion of forests to agricultural uses.

Additionally, the Ecosystem Services Framework resonates with recent innovations in conservation interventions, especially if the allocation of rewards gets linked to indicators of performance or incurred damages. Tourist revenue sharing schemes have become a common form of rewarding local people for their role in sustaining wild animals. Local people may not simply receive a share of tourism revenues on a regular basis but obtain payments on the basis of wildlife sightings by tourists (Clements et al., 2010). Alternatively, they may receive financial compensation for damage to crops or human health caused by wild animals (Sommerville et al., 2010). International NGOs or government agencies may even pay local people directly for conservation services. In Cambodia’s Bird Nest Payments initiative, local people are offered a monetary reward for reporting nests and are then employed to monitor and protect the birds until the chicks fledge (Clements et al., 2010). The most ambitious efforts to link ecosystem services to local income may occur in community-based ecotourism where local village-level tourism enterprises are intended to help to conserve globally threatened wildlife. The underlying idea is that such enterprises would link revenue received directly to long-term species conservation.

Thus, ecosystem services has gained increasing influence on the theory and practice of environmental management. The concept derives from a particular understanding of nature society relations and connects with the emergence of new-style governance interventions. With this observation I now turn to the next section, in which I introduce the theory and practice of environmental justice.

Environmental justice

Put simply, there are basically two ways to go about defining justice. Political philosophers tend to develop universal principles on the basis of certain social norms and then explore their applicability to concrete situations and problems. For example, John Rawls forwards an influential theory of social justice saying that the application of fair rules leads to just distributive outcomes (Rawls, 1971). He conceives of the well-known ‘veil of ignorance’ to create a hypothetical situation in which people judge distributive outcomes without knowing how these outcomes affect them personally. The thought experiment entices people to decide about the distribution of outcomes they would prefer from the perspectives of every person possibly affected by the decision.

Much of environmental justice theory follows a different approach to defining justice. Scholars like Ramachandra Guha and Joan Martinez-Alier (1997) demonstrate the multiple notions of justice informing the ‘environmentalism of the poor’ in the Global South (Martinez-Alier, 2002). David Schlosberg (2007) and Gordon Walker (2011) do not attempt to derive universal principles of justice in a deductive manner. Instead, these scholars seek to understand the notions of justice asserted by people and activists, and trace how some notions gain support or attract opposition in public discourse. They no longer assume the existence of universally shared notions of justice, nor do they seek to weigh the relative validity of competing notions in an objective, detached manner. The emphasis shifts to understanding the notions of environmental justice important to people and analyzing how these notions affect what people do – people including villagers, activists, practitioners, professionals, scholars, policy-makers and so on.

This ‘empirical approach’ conceives of environmental justice as multidimensional. Schlosberg (2004) identifies three dimensions: distribution, participation and recognition.1 Distributive justice is about the distribution of goods and bads between different people, such as access to clean water or exposure to air pollution. Demands for equitable distributions of environmental amenities and hazards have long been central to the environmental justice movement in the US and other industrialized countries. Yet, equitable access to biophysical resources and protection from natural hazards is equally important to struggles in the global South. The implications of distribution for human well-being are apparent.

Participation considers how decisions are made and is often referred to as ‘procedural justice’, including attention to the roles of different people and rules governing decision making. It is concerned with decisions over environmental matters in the narrow sense but also extends to wider public decision making over people’s affairs. For example, environmental activists in the Global North have lobbied against the e...