![]()

1 The Rhythms of Life

He who makes an enemy of the earth makes an enemy of his own body.

—Popol Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life

I began touching people therapeutically in Mexico beginning in 1973, when I lived in the jungle. The first people who came to my palapa, which over-looked the Pacific, did so because they were in pain or hoped to relax their mental strain. Palapas (thatched roof houses) get their name from the coconut palm fronds, which the men cut, measure, and then drag down the mountain by burro. They weave and tie the fronds to handcrafted ironwood frames, forming a huge straw hat over an open space. The roof sways and lifts with the wind, breathing and absorbing moisture like nostrils, mediating the inside and the outside, which often merge during the wet months in the jungle.

I first worked with the Mexican-Indian women, whose childbirths I had attended and who, because of the burden of multiple births and relentless work under the sun, often looked more like the mothers of their husbands than their wives. They brought their widely flattened sore feet and muscular shoulders, indented by ironlike bras that cut deep grooves across the top of the trapezius muscle. We shared village gossip and they were both honored and amused at my interest in traditional ways of healing. They told me that dried cow dung rubbed on the head cured baldness and then offered to demonstrate on me. They told me stories they had themselves been told about snakes that lived near the cascadas (waterfalls) and were known to be so dexterous that they could unzip your dress, get inside your pants, and get you pregnant. As we got to know each other better, they shared the trauma of their lives and loss of family members to the hardships of the jungle and sea: drowning, tetanus, amoebas exploding the liver, rape, and incest.

The women brought their little ones in when they fell off horses and hit their heads or fell out of hammocks or over the bow of the 40-horsepower pangas (small, outboard-powered fishing boats) as they hit the beach on an off wave, bruising the ever so tender sacral bone at the base of the spine. The men came in for treatment accompanied by their wives for the first session, just to make sure nothing untoward would take place. They sought relief for a variety of problems that usually had to do with occupational accidents: diving and the residual effects of too much nitrogen in the blood. Some of the men did not survive. Those who did rarely went diving again, nor did they ever walk the same way again.

One night Ezekiel, an ever-grinning, gold-toothed carpenter whose wife Ophelia made the best coconut pies in the village, was brought ashore. I was asked to his house where he lay in bed, inert and unable to urinate. I arrived amid the crowd of neighbors ritually dropping emergency money onto his bed, body, and clothes. No one needed to mention that the delay in reaching the charter medical flight to Acapulco, still an hour’s boat ride away over rough, full-moon seas, was due to lack of money. And while Zeke’s pockets were stuffed with pesos, his pants half on, belly exposed and scarred from previous battles unknown to me, I placed needles in his abdomen according to Chinese tradition to help him relax while he waited.

They said it was a miracle that Zeke survived. When he returned from the decompression chamber in Acapulco, 800 miles down the coast, he came for treatments and I worked on the firmly muscled legs, which betrayed him only when he walked. As I pressed hard into the core of his calves and the fascia lata on the outside of his thighs, he talked of the terror when he and his cousin Ruben were diving deep in search of sleeping lobsters and the 100-foot hose choked off the air at the same moment the panga stopped vibrating because the generator in the hull faltered too long.

A few years later, after my thatched roof house had burned to ashes, Ezekiel had fully recovered. I asked him to take a buzz saw and climb the 200-foot coconut palm, which grew out of the center of the zalate, the dying strangler fig tree that had given my house its name years before I arrived. Invariably, when passersby saw this symbiotic site for the first time, they would cry out with an astonishment that reflected their confusion about which tree came first, the zalate or the coconut. It was difficult without knowing their history, or nature itself, to tell by looking. The coconut tree appeared to rise straight up out of the middle of the fig; or was it the other way around? Like other parasitic intertwinings, the exact nature of their relationship was not evident upon first glance. However, the strangler fig, whose shape and skin was like elephant bark, got its name because its seed popped down into the coconut, which was already quite old when it ineluctably became host. The fig then proceeded to wrap its way around the palm and the landscape, its roots ruling the hectare of hillside like huge thighs and forearms elbowing their way through all my attempts to make steps from rocks on the path to my door. Twice yearly, the zalate bore fruit, dropping a hailstorm of green fig balls as quickly as they popped open. They tapped upon my roof around the clock, appreciated only by the bats, which, as they made their nightly pass through my house to see if the raicimo (bunch) of bananas were perchance left uncovered, left their sticky, fig-filled droppings on my floor.

The zalate died a slow giant’s death after the fire in 1983 and I missed cleaning up the thousand-figged parade that signaled another half year gone by. However, with the shade veil from the zalate gone, along with the garden, which now served as a burial ground for the shards of my grandmother’s heat-burst china, there was sunlight all day long. This prompted Ophelia to bring me several flowering bushes from her garden, some of them sweet red and pink cabbage roses to plant near my gate, which needed some color and a stubborn hold on its steep, eroding side. The last of the zalate’s roots did not dry and merge with the earth it had faithfully served until 6 years after the fire. By then, the roses were strong and in full bloom, and Ezekiel was able to climb the Coco to amputate the remaining limbs of the zalate. Then, sadly, as he shimmied down the smooth gray skin, he had to cut the still-live coco herself, who now without the support she had grown accustomed to, threatened to topple over onto my new roof whose dried fronds, barring another unthinkable fire, would not need replacing for another 4 years.

The majestic coconut is never willingly toppled, being the source of roof, oil, milk, and soap. But when she comes down her bounty is as rich in death as in life. My neighbor Alicia asked for two dozen thick, rippled rajas (slices) whose scratchy center resembles the scruff of the nut; when faced inside the house and tied side by side, they form walls against the sea air. The zalate then proffered her base as a table and six 3-foot stools for my kitchen, with four more going to Ophelia and Zeke. Finally, we ate her heart of palm, to which we added oil and lemon and gave thanks as we ate.

Over the years, I have come to understand the story of the zalate and its hold on my imagination in several ways. The relationship between the coconut palm and the huge strangler fig is not unlike the psychic intertwinings that occur between abuser and abused. One, a strangling parasite, takes over; the other, helpless to stop it, loses its identity and fears surviving on its own.

Having talked with many victims of psychological abuse or physical domination, I hear repeatedly the metaphor of possession and suffocation. One woman said of her long-term childhood abuser: “I felt that he was like a virus that had entered my bloodstream—and would be there always—even if and when I recovered.”

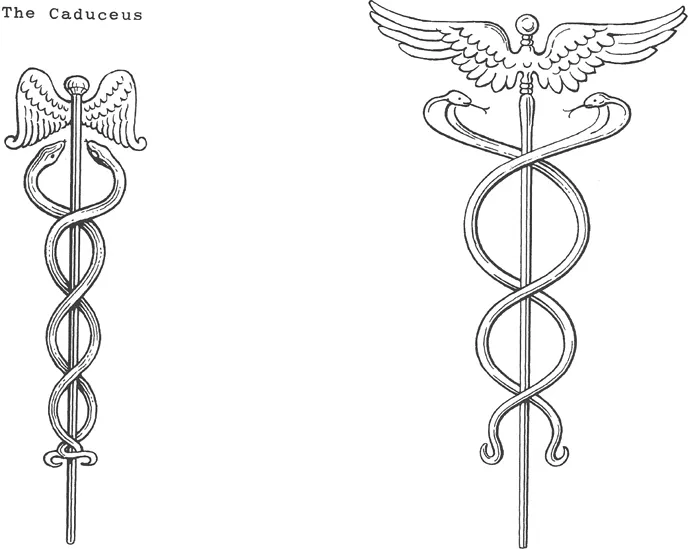

The need to cut the coco down even after it had stood for several years after the zalate had burned speaks to the inevitability of loss endured as a result of the psychological surgery that is often required to recover. Like the limbs wrapped around the coco, personality development takes place around and within the traumas of early life; extrication is never clear-cut and always entails loss. Yet the story of the zalate and the coco also contains images of hope. With the shade cover from the zalate now gone, I had a sprouting garden and light streaming into the house. Ezekiel recovered from his own pain and near paralysis to live a full life. The trees are also an image of healing; vines wrapped (helix-like) around a bold straight stalk remind me of the caduceus, also called the staff of Hermes, the cross-cultural icon of medicine and healing, representing the nervous system, the helix of descent into the underworld and ascent to the light of awareness (see Figure 1.1). Like the tree, the caduceus is a universal image of change and transformation.

Figure 1.1 Caduceus.

Source: Adapted from Polarity Therapy: The Complete Collected Works (Vol. 1), by R. Stone, 1987, p. 33. © 1987 by CRCS Publications. Reprinted with permission.

This image of the caduceus is of a strong central pole around which are wrapped two serpents that, representing consciousness, are a universal image of transformation, a symbol of shedding old skins. The caduceus serves as an image of the nervous system for many cultures. It is the central spinal cord and autonomic ganglia in allopathic neuroanatomy. For the kaballists, the mystical sect of Jews, it takes form as the tree of life. The Borgia Codex of Mexico displays a serpent and a centipede entwined, signifying the polarities.

For the Hindus this same image portrays the Kundalini, the she-serpent who sleeps at the base of the spine in the sacrum (sacred bone) and is awakened by the practice of yoga, bringing awareness and integration to the individual. Its closest analog in Western depth psychology is the unconscious. In the Greek myths, it is Hermes, messenger of the Gods (known by the Romans as Mercury) who travels to the underworld at the behest of Zeus to bring back the maiden Persephone (Kore), who is abducted and raped by her Uncle Hades. This myth of death and rebirth through pain and suffering is the enduring theme of healing from trauma. The caduceus symbolizes the archaic knowledge of yogis and shamans who access innate psychophysical capacities that are rooted in controlling the autonomic nervous system. Thus the individual controls the staff (spine) of Hermes by sending and receiving messages from the (inner) gods and transmutes the underworld of pain into the freedom of a chosen life.

The Rhythms Of Life

The experience of trauma is as old as humankind itself. One can only imagine the early hominid’s evolutionary urgency to fight or take flight—the response that lies at the heart of the autonomic nervous system’s response to trauma by increasing heart rate, blood flow, and oxygen levels. The emotion of fear primes the pump and energizes hormones like epinephrine, which clear the mind, sharpen the vision, and light the fire that excites the muscles to move quickly out of harm’s way. Escape from trauma brings (temporary) victory; the alternative is to freeze in inaction, leading to injury or death. Some of the functions of the autonomic nervous system, so called because they are “automatic” and instinctual, include the pulses of heart and breath, the periodic flush of gastric acids, the electrical charges of the brain, and the eliminative waves of bowels, which open and close the ileocecal “gate.” In health, these organs function rhythmically without conscious control, giving rise to the ebb and flow of life. The heart beats 40 to 220 beats a minute, depending on condition and activity. The breath cycle is completed 4 (yoga) to 20 times (aerobic) a minute, more or less. The brain emits electrical signals measured in cycles per second or hertz (Hz)—from approximately 2 to 3 cycles per second during deep sleep (delta), 4 to 7 Hz (theta), 8 to 12 (alpha), 13 to 18 (beta), and above 40 (gamma). Whether electroencephalographic (EEG) patterns actually drive the brain (Evans, 1986) or consciousness drives EEG, as the renowned psychophysiologist and physicist Elmer Green insists (E. Green, personal communication, November 11, 1998), we have capacities to gain control over these processes. This forms the basis for self-regulation practices such as meditation or the modern technological equivalents, biofeedback, neurofeedback, or devices such as musical or electrical stimulation devices that entrain alphatheta brainwave patterns. Though traditionally it has been believed that people are in one or another state, such as alpha or theta at one time, it is now thought that people are in all EEG frequencies simultaneously in different areas of the brain (Wilson, 1993).

This timely ebb and flow of natural rhythms—the polarized dynamic of opposites represented as sleep and wakefulness, inhalation and exhalation, systole and diastole, beta and delta—are severely compromised by trauma. An understanding of the methods that affect consciousness and brainwave function is useful for both the clinician and client in the treatment of trauma. Many of the methods proposed in later chapters address ways to regulate states of consciousness and their brainwave analog for the purpose of healing.

Healing is rooted in the rhythms of reconciliation: forces that shift shapes as inner and outer, darker and lighter, hotter and colder, closer and farther. In Chinese tradition and many tribal cultures, the rhythms of the body are considered one with the natural world. Disease or illness results when one becomes out of balance with these forces. Practitioners of traditional Chinese philosophy and medicine refer to these dynamic polarities as yin and yang, mediated by a transitional third energetic phenomenon, called Tao or Balance. Rooted in concepts dating back to the 4th century BCE, yin and yang originally referred to “the shady side of the hill” and “the sunny side of a hill,” respectively (Unschuld, 1985, p. 55). Ayurvedic medicine, the practice of Hindu culture in ancient India dating as far back as 2300 BCE (Amber & Babey-Brooke, 1966; Rao, 1968) refers to these concepts as the ida and pingala, mediated by a third principle, shushumna. Both traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic healers refined the art of diagnosis by palpating the pulses—considered to be the rhythms that are “witness of the soul” (Amber & Babey-Brooke, 1966). Randolph Stone, the cranial osteopath and originator of polarity therapy, detected three pulses, which he called frog, snake, and swan (Stone, 1986), ostensibly due to the quality of the feel and movement of blood and the significance to health of these variations.

The reconciliation of opposing yet complementary forces has particular import for the treatment of posttraumatic stress. Trauma disrupts endogenous rhythmic cycles of function and cyclic movement is replaced by a state of fixation. This is well established by conventional medicine as reflected in the concepts of autonomic hyperarousal and hyper/hypoactivity of the hypothalamic-adrenal-pituitary axis. The autonomic nervous system is composed of three branches, the sympathetic, the parasympathetic and the most recently identified, the ventral vagal complex or social nervous system (Porges, 2011). The restoration of balance within these forces—whether called yin and yang, ida and pingala, or parasympathetic and sympathetic—is at the heart of Eastern and Western medical traditions alike.

Rather than sustaining the natural flow of oscillating life force, trauma causes autonomic fixation and loss of the normal range of body regulation, including extreme, uncontrollable cycles of response characterized by opposing fluctuations of cognition, behavior, and kinesthetic perception. It is the restoration of flexible movement instead of fixation by balancing these extremes that poses the central dilemma for the integrated mind/body treatment of traumatic stress. Drawing on this theme from both Eastern and Western traditions and identifying and balancing the oscillating rhythmic functions provides a unifying approach to holistic therapy.

The convergence of traditional and contemporary healing approaches that has been catalyzed during the past 30 years has antecedents from a rich historical past. The centrality of balance to healing is found in the word medicine, which derives from the Sanskrit verb maa, meaning “mother” and “to measure,” and manya, meaning “to move back and forth; to align in the middle” (Frawley, 2001). The principal icon of balance in both Eastern and Western modes of medicine is the caduceus, or staff of Hermes. It signifies the reconciliation of polarized forces in nature and, in the 16th century, became the alchemical symbol for the evolution of the soul. It serves as a visual icon of modern medicine and represents the role of the autonomic nervous system in the transmutation of trauma.

Alchemy was the first chemistry of the Western world concerned with the esoteric science of transmuting the two subtle energies of sulfur and quicksilver into gold. Alchemy’s subtext is the esoteric art of transforming spiritual consciousness. It was mercury, associated with the mind, that facilitated the action between the two energies. The alchemical association with mercury was the mind, “forever darting about to and fro” (Evans, 1986, p. 116). Gaining control over unconscious or automatic functioning is the basis of many healing traditions, and is an important key to healing the mind/body split that results from trauma. The caduceus is first associated with the Babylonian mother goddess about 4000–1955 BCE and is later identified with Ishtar—the goddess of fertility, love, and war—and Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty. The word caduceus is Latin, derived from the Greek word Kerykeion, which is associated with the word keryx, meaning “herald” or “to announce...