![]()

Part 1

Psychological Constructions

Anxiety of Isolation and Exposure

![]()

Chapter 1

Taking Comfort in The Age of Anxiety

Eero Saarinen’s Womb Chair

Cammie McAtee

Almost immediately upon its debut on the home furnishings market in 1948, Knoll’s chair no. 70, or “Womb Chair,” as it was quickly dubbed, achieved cult status as a design object (Figure 1.1). Emerging at the beginning of the era of prosperity, the chair enjoyed consistent popularity from the 1940s into the 1960s, ironically becoming a “classic” in a period defined by planned obsolescence and the cult of the new. Arguably Knoll’s signature piece of the first two decades of the postwar period, in recent years the Womb Chair has resurfaced as an icon of mid-century modernism.1 Its well-known designer, the Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen (1910–1961), was a leading protagonist among the group of American practitioners who would become known as the “form givers.” Although he adhered to the tenets of modern architecture as defined by Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier, Saarinen sought to expand the vocabulary and range of expression of architectural form, a goal he achieved in such buildings as the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in St. Louis (1947–1965), the David S. Ingalls Hockey Rink at Yale University (1956–1959), and the Trans World Airlines Terminal at John F. Kennedy Airport, Idlewild (New York) (1956–1962).

Designed between 1946 and 1948, the Womb Chair predates these feats of engineering and sculptural form.2 Through this, Saarinen’s interpretation of the American “easy” chair, the designer challenged the popular perception that modern design was cold and uncomfortable. The Womb Chair confronts the poles of style and comfort, of artwork and everyday object. Contrasting hardness and softness, rigidity and flexibility, mass and line, the chair was artfully assembled to bring a sense of drama to the postwar home.

The Womb Chair has most often been examined from the point of view of Saarinen’s trajectory as an object designer and architect and for the technological innovation it brought to furniture design.3 This essay opens up its interpretation to consider the impact of America’s emotional state on its design. I examine the Womb Chair within the context of the Age of Anxiety, as the postwar years were popularly known. Anxiety was a persistent subtext within American culture during the country’s most optimistic years, pervading the domestic realm as well as other social, political, and cultural arenas. I explore what this “overtly anxious” culture, as one observer called it, contributed to both Saarinen’s design and the reception of the chair, including Saarinen’s own understanding of what he had created. I argue that the chair is testimony to Saarinen’s intuitive manner of designing, one that ultimately sought to create affective forms that engaged their users—in this case, sitters—on deeply psychological as well as physical levels.4 But I will first consider the form of the chair and its formal origins. As my argument is supported by the physical experience of the Womb Chair, its haptic as well as optic qualities will be referenced throughout.

1.1

Womb Chair (Knoll chair no. 70) with Ottoman, 1946–1948 (Unknown photographer)

Organic Chair

A seemingly simple construction, the Womb Chair is actually a complex, even complicated, assemblage.5 Wider than it is tall and almost as deep, the chair consists of two main elements: a large curving fiberglass seating shell and a tubular steel frame that loops under the arms and beneath the seat, where it meets a shorter curved piece supporting the front of the chair. The rounded form of the shell is interrupted by a deep U-shaped well at its base; a void that breaks the profile into three angles. Padded with a layer of foam rubber on the upper “seat” side, the shell, including the opening at the back, is completely enveloped by a woven textile. Approached straight-on, the shell seems to almost levitate above the supporting structure, its curving form delicately cradled by, rather than attached to the thin structural members. The final components are two cushions, down-filled in the early years of the chair’s production, which fit over the seat and the well.

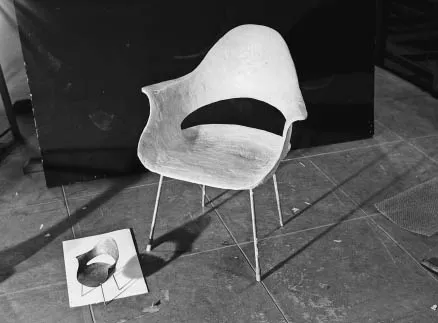

1.2

Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen with Don Albinson (fabricator), first full-scale prototype and small model of “Conversation” chair for the Museum of Modern Art’s “Organic Design in Home Furnishings” exhibition, September 24–November 9, 1941 (Unknown photographer, March 1941)

The formal origins of the Womb Chair lie in part within a series of chairs co-designed by Saarinen and Charles Eames for the Museum of Modern Art’s 1940 competition “Organic Design in Home Furnishings” (Figure 1.2). Taking first place in their category, the chairs catapulted Eames and Saarinen into the forefront of American design and went far towards launching their independent careers. The success the series of chairs and sofa found with the competition jury relied upon the careful negotiation of good design and contemporary art. The curvilinear shapes of the chairs represented significant new directions for both designers. While Saarinen’s earlier forays into furniture design were closely tied to his father’s work and had drawn on Art Deco and modern design of the 1920s and 1930s, Eames, for his part, had experimented with historicism as well as streamlined Moderne in his architectural and design work. Leaving behind Constructivist and Functionalist design of the 1920s and 1930s, they instead took their inspiration from biomorphic forms, which had been introduced into art in the mid-1910s and further developed in the 1930s in the paintings of Joan Miró and the three-dimensional constructions of Alexander Calder, and had found expression more recently in the decorative arts through the furniture of Alvar Aalto and Frederick Kiesler.6 It was Saarinen who gave the chairs their strong sculptural quality.

1.3

Full-scale model of a Grasshopper Chair (Knoll chair no. 61), 1943–1946 (Photograph by Harvey Croze, December 1946)

As a first step towards putting them into commercial production, the Museum of Modern Art commissioned the Massachusetts-based furniture manufacturer Heywood-Wakefield and the Haskelite Manufacturing Corporation of Chicago to make prototypes of all the notable competition entries for an exhibition. Wartime material shortages, however, made large-scale production of Saarinen’s and Eames’s chairs impossible.7 In the end, the long-term significance of the “Organic Design” chairs lay in the directions their designs took the two young designers. They encouraged Eames and his collaborator and wife, Ray Kaiser Eames, to further explore molded plywood resins, thus initiating a research project that stretched into the 1950s, culminating in their celebrated leather padded Lounge Chair and Ottoman (1956). And though he was increasingly occupied by the demands of the busy architectural practice he shared with his father Eliel, Saarinen, too, continued to work on furniture. In 1946, his Aalto-esque bentwood Grasshopper Chair (1943–1946) was brought out by Knoll Associates, the interior and furniture design company headed by Hans Knoll and Florence Schust Knoll (Figure 1.3).8

Chair No. 70

The commission of the Grasshopper Chair was part of Florence Knoll’s larger project to put new furniture designs by American architects and designers into production alongside well-known pieces by Europeans.9 She envisioned these works as functioning as sculptural elements within domestic environments and within the business interiors she created for some of the most powerful companies of the time. Florence Knoll herself designed the background pieces, or as she saw them, the architecture.10 She drew upon her friendships with several designers closely associated with the Cranbrook Academy of Art, where she had studied in the late 1930s.11 She was especially close to Saarinen; the two had even been romantically involved for a brief period.

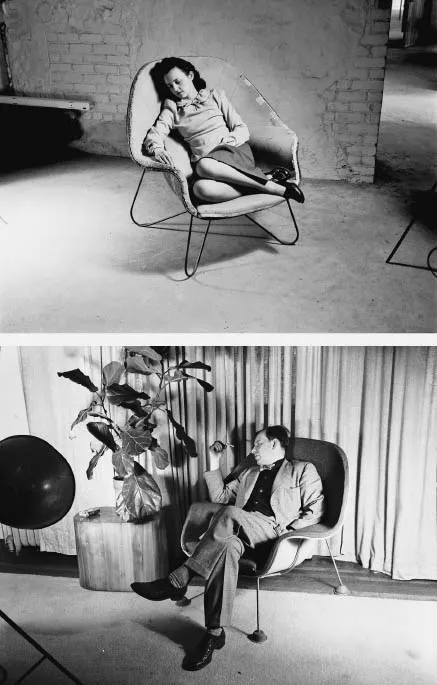

1.4

Above: Cranbrook student Agnes LaGrone Steen resting in Womb Chair prototype with “Butterfly” Chair base, 1946 (Photograph by Harvey Croze, December 1946)

Below: Eero Saarinen seated in Womb Chair prototype with exposed shell in the living room of his home in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, 1947 (Photograph by Harvey Croze, 1947)

In 1946 Florence Knoll approached Saarinen to design another chair for the company. For this piece of furniture she had a specific program in mind, later recalling that she asked Saarinen to create a chair “like a big basket of pillows that I could curl up in.”12 As the story goes, Saarinen abandoned the two-dimensionality of the Grasshopper Chair and returned to the molded three-dimensional prototypes he had developed with Eames in 1940. The design of what would be officially known as Knoll’s chair no. 70 loosely blended the “Conversation” and “Lounging shape” prototypes, but the seating shell was expanded in width and depth and placed closer to the ground, giving it a more informal quality. The expression of the supporting members proved to be a thornier problem. Clearly dissatisfied with the four conventional legs he and Eames had proposed for the Museum of Modern Art chairs, Saarinen experimented with many variations, even briefly trying out the parabolic base of Jorge Ferrari-Hardoy’s Butterfly Chair (1938), which had been brought into production by Knoll in 1947–1948.13 The sinuous line complemented rather than broke with the form of the shell (Figure 1.4). A compromise between the two structural systems was eventually adopted, likely to balance formal issues with those of stability. The desire for a clean, organic support initiated what Saarinen later called his mission to “clear up the slum of legs,” which was achieved with the Pedestal Chair in the mid-1950s.14

Plastic Chair

Where the design most significantly departed from its predecessors was its use of plastic for the seating shell. Saarinen appears to have had plastic in mind from the very outset. It is not surprising that he was familiar with this new material at this early point. Even before the close of the Second World War, the plastics industry had begun to aggressively market its products for domestic use in the postwar period. In the spring of 1946, the same year Saarinen began working on the chair, the Society of the Plastics Industry organized the first public exhibition of their products. Held for a six-day period in New York, the exhibition attracted over 87,000 visitors. Alongside hundreds of other new materials, Fiberglas, a trade name that came to describe both polyester plastic reinforced with fiberglass and glass-reinforced plastic (both of which functioned as plastic not as glass), made its public debut.15 Hans and Florence Knoll undoubtedly visited the exhibition, and it seems likely that Saarinen, with his well-known interest in new technologies, was also in attendance and saw first-hand the fiberglass fishing rods, skis, baby strollers, and one-piece boat frame on display. Moreover, through his work for the General Motors Corporation, Saarinen was well aware of the interest the material was generating in the automobile industry. In 1946 the first postwar prototype for a fiberglass automobile body came out.

Saarinen’s and Florence Knoll’s turn to plastic was more than timely; it was culturally significant. As historians of technology and popular culture have shown, the rise of plastic neatly segued with the greater affluence and corresponding consumer confidence that many Americans experienced in the postwar period. Plastic’s malleability, its capacity to support bright, dense color and a variety of textures, its ease of production and relative cheapness all combined to make it the perfect material to express the ideals of a consumer society that privileged endless change, transformation, and newness. As well as enjoying the flexibility and functionality of Earl Tupper’s standardized serving and storage containers (1947), the consumers who purchased them could also agree with Roland Barthes’s prediction that “ultimately, objects will be invented for the sole pleasure of using them.”16 Saarinen’s chair no. 70 thus anticipated the assimilation of a material that would develop a deep dialectical relationship with 1950s culture.17 For Saarinen, however, the choice of a material that could be easily molded was based on its potential to express sculptural form, which he gradually came to believe was the chief concern of design.18 With this issue in mind, he optimistically brought plastic forward as the material of postwar furniture design. In 1946, however, he was unconcerned with expressing the material’s specific visual or tactile qualities; there were signs that he in fact was intent on hiding them. In this regard he...