![]()

1

A GENDERLESS FUTURE?

What were they thinking! In March, 2010 the New South Wales (Australia) Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages sent Scottish-born Norrie May-Welby an immigration certificate listing her as “sex not specified.” The bureaucratic decision to allow May-Welby to immigrate without specifying his/her sex or gender came after an extended legal battle. As it turned out, May-Welby’s official genderlessness was a way station in a struggle that continues as of this writing. Following intense publicity, the Registry backtracked, claiming it did not have legal authority to produce a gender neutral certificate. May-Welby is suing. Moreover, May-Welby is not the only person on earth who wishes to live gender free. Reporters Barbara Kantrowitz and Pat Wingert suggest that a growing number of people consider themselves gender neutral (Kantrowitz & Wingert, 2010).

Confusion about gender categories (Male? Female? Neither? Both?) seems to be perennially newsworthy. Take the case of the South African runner Caster Semenya. During the summer of 2009, she beat the women’s 800-meter running record by several seconds. Although her achievement remained a good 18 seconds off the men’s record, her breakthrough prompted complaints that Ms. Semenya was really a man. An international scandal erupted when the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), track and field’s governing body, barred her from competition until she completed a gender test.

A what? What on earth is a gender test? You might think it is simple to tell who is male and who is female. Indeed, sometimes it is simple. But not always. More than a year into this story the IAAF decided to allow Semenya to resume competition. In August of 2010 she won handily in women’s races in Berlin, Germany and in June 2011 she came in third in competition in Oslo, Norway (“Bolt Blitz in Oslo; Athletics,” 2011). But the IAAF did not release the gender test results, rightly maintaining that these contain Caster Semenya’s personal and very private health information. So we remain in the dark about what a gender test actually is and how, in this case, it gave the IAAF the information it needed to allow Semenya to resume competition (Caster Semenya, 2010).

Genderless Australian immigrants. Record breaking runners who may not really be women. What then, are we to think about the future of gender? Is it really disappearing (I doubt it); should there be more than two legal gender categories (possibly); do we know enough about sex and gender to deal intelligently with the idea of a genderless future (no)? After all, don’t chromosomes that join together at fertilization fix sex and gender for a lifetime (no)? Don’t societies all think (more or less) the same way about sex and gender (no)? Have they always thought the same way about sex and gender (and no again)? Perhaps there are things about sex and gender that we can never know. And if so why can’t we know them? These are among the questions this book addresses. Perhaps you thought you already knew what sex was, what gender was, and all of the essentials about human sexuality. And perhaps so. But in this book I start at the beginning with developing embryos and explore what we know about sex and gender and how well we know it. Then, based on the knowledge gained, maybe we can look at the future of gender, if not definitively, perhaps and at least, intelligently.

![]()

2

OF SPIRALS AND LAYERS

Where Do We Start?

There is no right place. Do we begin with the story of boy meets girl (or girl buys sperm at a sperm bank?), the development of eggs and sperms, or the more traditional moment of fertilization (sperm fuses with egg)? No matter what point we choose, we start in the middle of the story of sex and gender; from there we can race forward, and end up looping back (Figure 2.1). For now, let’s start with a traditional framework, fill in some of the things we currently know about the biology of sex development, and then loop back to offer some interesting tidbits that complicate the basic story just a bit.

Figure 2.1 Sex spiral.

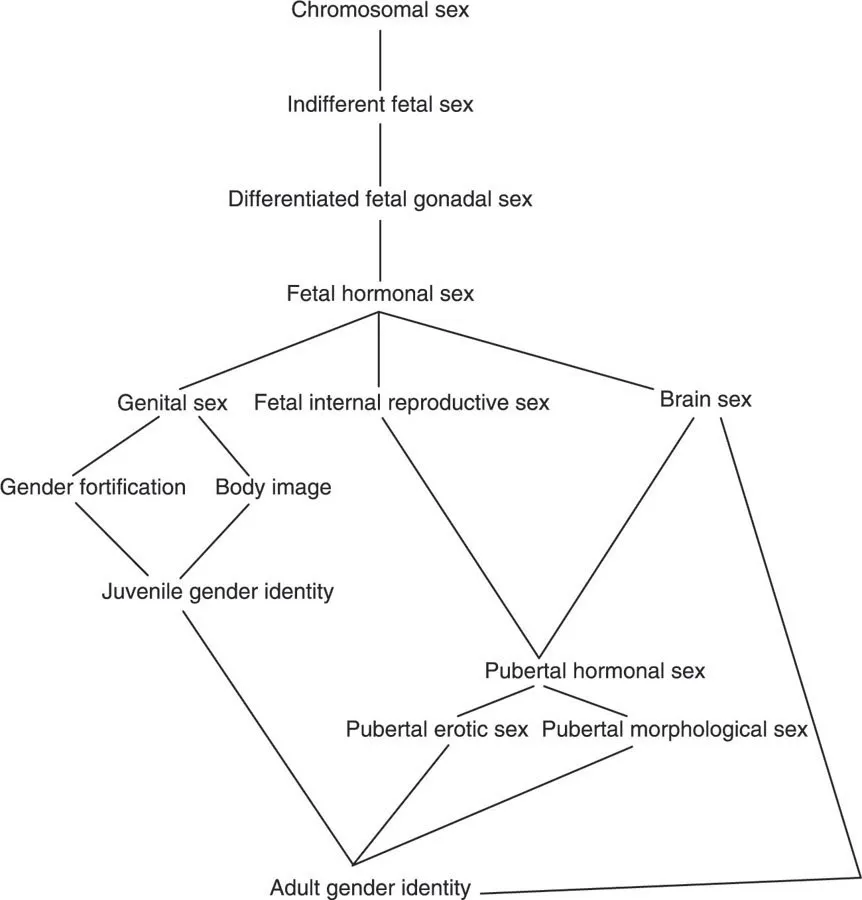

In the 1950s psychologist John Money and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins University pioneered the study of sexually ambiguous patients. As he worked with children and some adults born into the world with unusual combinations of sex markers (testes and a vagina, ovaries and a penis, two X chromosomes and a scrotum, and more) Money developed a layered model of sex and gender (Figure 2.2). He started with fertilization. Human males produce two kinds of sperm—one with an X chromosome plus one each of so-called autosomes, and the other with a Y chromosome and one each of the so-called autosomes. Later (Chapter 3), I will discuss what we know about how the X, the Y, and the autosomes contribute to the development of sex. But for now, let’s stay focused on the bigger framework. At the same time that the male produces X- or Y-bearing sperm, females, having two X chromosomes, produce only one kind of egg—X-bearing with a full set of autosomes. Egg and sperm join forces. The result is a double set of autosomes plus an X and a Y or a double set of autosomes plus two Xs. Voilà! We have what Money called chromosomal sex-layer 1 in the multilayered phyllo dough (or for those of Germanic extraction—strüdel) pastry we call sex-gender.

Figure 2.2 Layers of sex.

Usually, about 8 weeks after conception, embryos with a Y chromosome develop an embryonic testis and by 12 weeks, those with two Xs form embryonic ovaries. Once a developing fetus has gonads (the general term for testes or ovaries) it has, by definition acquired fetal gonadal sex. The fetal gonads quickly get down to business and start making hormones important to the embryo’s progress. Again, I will circle back with details in the next chapter. But for now, all we need to know is that once the fetal gonadal hormones appear we can say that the fetus has acquired a fetal hormonal sex. Fetal hormonal sex contributes to the formation of the internal reproductive sex (the uterus, cervix, and Fallopian tubes in females and the vas deferens, prostate, and epididymis in males). As the fetus nears the end of its fourth month of development, fetal hormones complete their job of shaping the external genitalia (genital sex)—penis and scrotum in males, vagina and clitoris in females. By birth, then, baby has five layers of sex. And, as we shall see, these layers do not always agree with one another (Gilbert, 2010).

But we have only begun to layer. At birth, Money and his colleagues pointed out, the adults surrounding the newborn identified sex based on their perception of external genital anatomy (genital dimorphism); this identification initiated a social response that began the gender socialization of the newborn. Note the hand off from sex to gender. Money and others use gender to designate an individual identity or self presentation (Green, 2010; Money & Ehrhardt, 1972). These are always structured to be specific to a particular culture. For example, in the United States a masculine or male-presenting woman would wear pants, have short hair, and refrain from using make-up. In contrast to most psychologists, many sociologists use gender to refer to social structures that differentiate men from women (Lorber, 1994). These might seem to be relatively innocuous, for example, separate public bathrooms, or a requirement that we designate our sex on official documents such as passports or driver’s licenses. Or they might really restrict one’s freedom, as, for example, laws that forbid women to drive or vote.

Table 2.1 Lorber’s subdivision of gender

Source: Adapted from Lorber (1994: 30–31)

I will use “gender” in both senses, but whenever I refer to the body and/or individual behaviors, I will use the term “sex.” An individual, therefore, has a sex (male, female, not designated, other); but they engage with the world via a variety of social, gender conventions. Each individual, thus, manufactures a gender presentation that can feed back on the individual’s sex, and is interpreted by others using the specific gender frameworks of an individual’s culture. Gender, then, is definitely in the eye of the beholder. Sex and gender presentation are in the body and mind of the presenter.

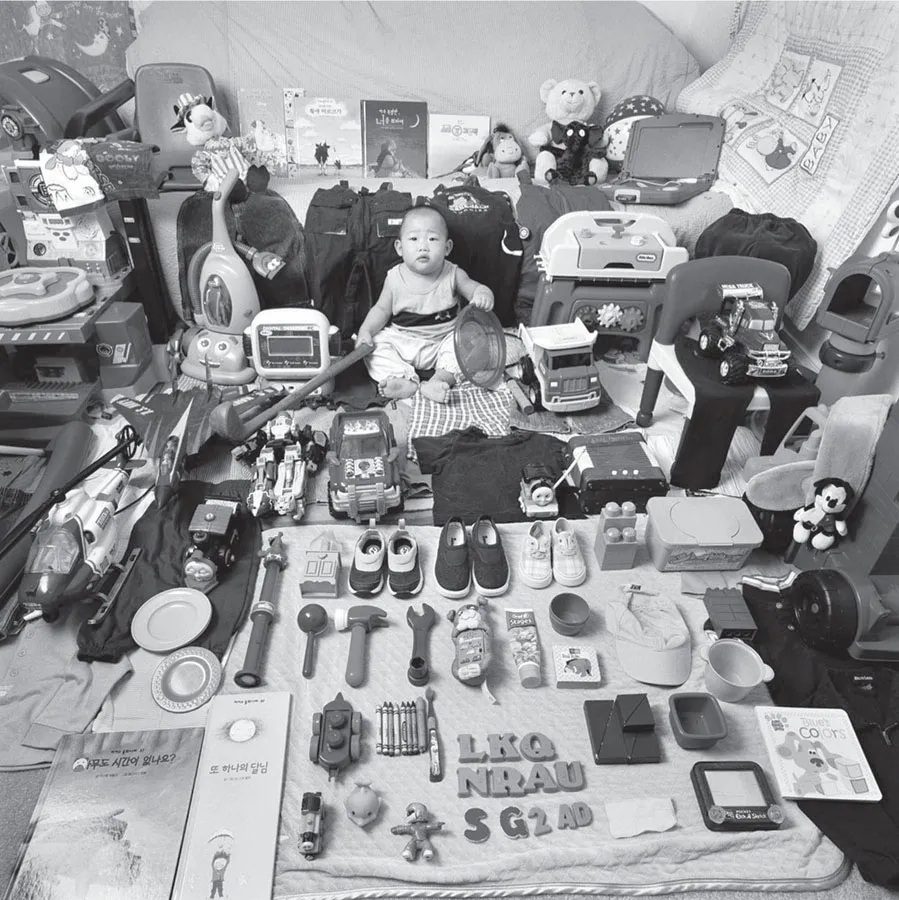

But back to newborns. The social response to the genital sex of the newborn is intense. Consider two markers—clothing and toys. Artist JeongMee Yoon has engaged in a several year project rendering images of children’s pink and blue things. In Figure 2.3 Yoon presents us with Lauren and Carolyn’s pink things and Ethan’s blue things (Yoon, 2006). Well, to be honest, if you are holding a print version of this book in your hands, the images are in black and white. But if you go to the book’s website at www.routledge.com/cw/fausto-sterling you can see the full color effect of these works of art. The images hold a lot of information. Not only is the intensity of the color scheme striking; noteworthy as well is the preponderance of clothing, dolls, and stuffed animals among Lauren and Carolyn’s things. This contrasts with the tools, sports equipment, and trucks in Ethan’s possession.

Figure 2.3(a) Lauren and Carolyn and Their Pink Things 2006, by JeongMee Yoon (http://www.jeongmeeyoon.com/aw_pinkblue.htm).

For color versions of these figures please go to www.routledge.com/cw/fausto-sterling

Figure 2.3(b) Ethan and His Blue Things 2006, by JeongMee Yoon (http://www.jeongmeeyoon.com/aw_pinkblue.htm).

What options do parents have when they start buying or accepting gifts for their newborns? Consider the Babies’r Us website1, which categorizes infant clothing as baby girl, baby boy, or neutral. Whereas the main theme of gender neutrality seems to be yellow baby ducks, newborn outfits for boys sport blue, brown, green, white, or black clothing with a monkey or sports themes. Newborn girl outfits sport purple, pink or pink trimmed, pastel light greens, or white colors with flower logos. The rare neutral infant suit was white with a giraffe logo.

The toys section had more overlap in items said to be for either a boy or a girl. But the differentiation remains clear. Although there are no designated gender neutral toys, both boy and girl toy categories featured the same Baby Einstein products. But the boys’ page also featured a large variety of trucks, and the New York Yankees ABC My First Alphabet Book (2009). To be fair, the girls also had some trucks, albeit in neutral, yellow, or “girl-colored,” i.e. pink, vehicles. Other girlie offers included a Leap Frog Cook and Play Potsy Toy and a Fischer Price Little People Nativity Playset. Money dryly refers to all this pinkish, bluish hullabaloo as “other’s response” but I think it merits a better name: gender fortification.

Infants are born to explore the world. They start by assimilating information from the senses. They sense touch, warmth, light, and sound. They experience hunger and feeding. They hear their own crying and experience a caregiver’s response. They respond to the discomfort of a wet, full diaper, and experience sensations as an adult cleans, dries, and powders their genitals, perineum, and anal area. From these simple beginnings infants develop a sense of their own body, a sensory body image. The anatomy of the external genitalia affects this developing body image, and this is yet another level of sexual formation— the sex of the body image (see Figure 2.2).

But wait! There’s more! Money links one more layer of sex to fetal gonadal sex, something he calls brain dimorphism, and I am calling...