- 254 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Effective Teaching in Higher Education

About this book

Assists academic staff to develop their effectiveness as teachers and improve their students' learning by giving practical guidelines and suggestions for teaching and a series of activities.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1: Introduction

A wise man learns from experience and an even wiser man from the experience of others.

(Plato)

A PROLOGUE

Lecturers in universities and polytechnics have three functions: teaching, research, and management. This book is concerned with the teaching function. If you believe that teaching in higher education is a trivial non-assessable pursuit then this book is not for you, for the book is based on two interrelated assumptions. First, that effective teaching is a complex, intellectually demanding, and socially challenging task. Second, that effective teaching consists of a set of skills that can be acquired, improved, and extended.

Effective teaching is intellectually demanding in that it requires the teacher to know, in a deep sense, the subject being taught. To teach effectively you need to be able to think and problem-solve, to analyse a topic, to reflect upon what is an appropriate approach, to select key strategies and materials, and to organize and structure ideas, information, and tasks for students. None of these activities occurs in a vacuum. Effective teaching is socially challenging in that it takes place in the context of a department and institution which may have unexamined traditions and conflicting goals and values. Most important of all, effective teaching requires the teacher to consider what the students know, to communicate clearly to them, and to stimulate them to learn, think, communicate, and perhaps in their turn, to stimulate their teachers. In short, to teach effectively you must know your subject, know how your students learn, and how to teach.

But clearly, effective teaching is not solely dependent upon the teachers. Students too have responsibilities to learn. Sometimes these responsibilities need to be made explicit. Often an indirect but powerful way of improving your teaching is to improve the ways in which students learn. Hence a theme in this book, particularly the final chapter, is how you can help your students to learn. But whereas students’ responsibilities to learn may be described as individual and personal, ours as teachers may be regarded as collective and professional. Hence the importance of developing, monitoring, and assessing teaching by individuals and by departments.

WHAT IS TEACHING?

Before embarking upon the study of various methods of teaching it seems appropriate to consider the following question: what is teaching? Teaching may be regarded as providing opportunities for students to learn. It is an interactive process as well as an intentional activity. However, students may not always learn what we intend and they may, sometimes alas, also learn notions which we did not intend them to learn.

The content of learning may be facts, procedures, skills, and ideas and values. Your goals in teaching, and therefore for the learning of your students, may be gains in knowledge and skills, the deepening of understanding, the development of problem solving or changes in perceptions, attitudes, values, and behaviour. (Students’ goals may, of course, be more pragmatic—passing examinations!) Given that teaching is an intentional activity concerned with student learning, it follows that it is sensible to spend some time on thinking and articulating your intentions in teaching a particular topic to a group of students—and on checking whether those intentions are realizable and were realized.

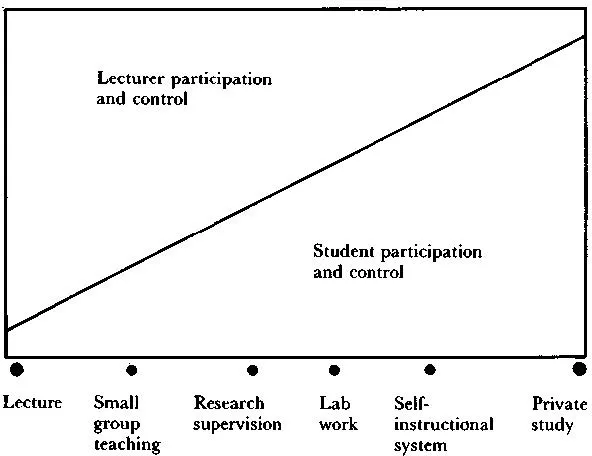

The various methods of teaching may be placed on a continuum. At one extreme is the lecture in which student control and participation is usually minimal. At the other extreme is private study in which lecturer control and participation is usually minimal. It should be noted that even at each end of the continuum there is some control and participation by both lecturer and students. Thus in lectures students may choose what notes to take, whether to ask questions—or even disrupt the class. A student’s private study is likely to be influenced by the suggestions of the lecturer, the materials and tasks that he or she has provided and the texts that are made available in the library.

Between the extremes of the continuum one may place, approximately, small group teaching, laboratory work, and individual research or project supervision. The precise location of these types of teaching is less easy. For each type of teaching contains a rich variety of methods involving varying proportions of lecturer and student participation. For example, small group teaching may be highly structured and tightly controlled by the lecturer or it may be free- flowing discussion in which the lecturer prompts or facilitates occasionally. Laboratory work may be a series of routine experiments specified precisely by the lecturer or a set of guided inquiries in which the student develops hypotheses to test, chooses methods, and designs appropriate experiments. A particular research supervision may be wholly lecturer directed, another may be wholly student directed. These notions are discussed in more detail in the relevant chapters. In the meantime you might find the continuum useful in helping to clarify your intentions with regard to student participation and control.

Figure 1.1 A continuum of teaching methods

This book has been written to help you to reflect upon, experiment with, develop, and appraise your own teaching. In a sense the book is a starting-point for teachers in higher education who want to research their own teaching and how their students learn. The text focuses upon the major methods of teaching—lecturing, small group teaching, laboratory work, and individual research or project supervision—and it provides ways of helping students to improve their learning in class and in private study.

Chapters in the text contain brief outlines of relevant research, guidelines for teaching effectively which are based upon the research, and some practical suggestions for planning and assessing your teaching. At the end of each chapter are a set of activities which may be tackled individually, in informal study groups, or as part of a workshop or course. All of the activities have been used by the authors in workshops on teaching and learning. Notes and comments on the activities are provided at the end of the book with some suggestions for organizing workshops based on the content of the book. The book does not consider student assessment or computer-based learning; these are considered in Beard and Hartley (1984) and McKeachie (1986). Nor does the book attempt to integrate systematically knowledge of particular academic subjects with knowledge of the processes of teaching and learning. Such a task is best assumed by the readers who, after all, know their subjects and their underlying values. The book does, however, provide examples drawn from different academic fields which may help you to see ways of using various approaches to teaching in your own subject—ways which you may not have previously considered.

The book may be used in at least four ways. First, you may simply read it. This will take most people no more than two or three evenings. It will be time well spent since you will learn of various strategies and activities that you can use, and of the research on which they are based. Second, you can read the book and try out the activities on your own or with small groups of colleagues. This will provide practice, reflection, and perhaps discussion of the issues involved, thereby deepening your understanding and developing your expertise. Third, you can use parts of the text as the basis of short courses on different methods of teaching and learning. The notes and comments as well as the activities are of value for this purpose. Used in this way you will learn from watching your colleagues at work and discussing with them various approaches. The fourth way of using the text is for organizing, and participating in, a systematic course on teaching in higher education. Such a course would take about twenty-one days and it might best be tackled in blocks of time distributed throughout the year. This approach would give participants time to learn new approaches, to reflect on them, to use them in their teaching, and to bring back to the course their new experiences and problems.

EFFECTIVE TEACHING

Effectiveness is best estimated in relation to your own goals of teaching. Thus what counts as effective in one context may not be so in another. A beautifully polished lecture which provides the solution to a problem may be considered effective if the goal was merely conveying information. If the goal was to stimulate the students to develop the solution then the polished lecture may be regarded as ineffective. However, you should be wary of the argument that bad teaching is effective teaching because it forces students to study more intensely. Leaving aside the differing views of ‘bad’ teaching, such an argument may be a rationalization for not improving your teaching. For us, bad teaching reduces motivation, increases negative attitudes to learning, and yields lower achievement. In our view it is better to teach clearly and stimulate the students to think by drawing their attention to particular issues than it is to be deliberately confusing.

Although effective teaching is best estimated in relation to your goals, there are some features of teaching on which there is both a consensus among lecturers and evidence from studies of student learning. Generally speaking, effective teaching is systematic, stimulating, and caring (McKeachie and Kulik 1975; P.A.Cohen 1981; Marsh 1982). Obviously the emphasis on these factors varies between lecturers and subjects and each of these factors is complex and, in practice, challenging.

Effective teaching is sometimes equated with successful teaching— that is, the students learn what is intended. While this argument has some appeal, it is not the whole of the matter. Effective teaching is concerned not only with success but also with appropriate values. A lecturer may teach Anglo-Saxon grammar so successfully that all the class pass the examination—and then drop Anglo-Saxon. Was the lecturer an effective teacher? The answer depends in part on whether you value attitudes more than short-term gains in knowledge. Thus in considering research on effective teaching it is important to consider successful teaching strategies in the context of what lecturers and students value. This procedure is adopted in the subsequent chapters of this book.

ACTIVITIES

These activities, and those in subsequent chapters, are designed to encourage the reader to think, discuss, and try out various suggestions. Some of the activities may be tackled privately, others are best tackled in small groups. There are notes and comments on some of the activities. It is not necessary to tackle all the activities in each chapter but do tackle some. Obviously you may modify the activities for use with particular groups of colleagues.

1.1 Research is sometimes described as ‘organized curiosity’ and teaching as ‘organized communication’. How far do you agree?

1.2 Teaching ability is often not estimated for promotion purposes on the grounds that there are no objective measures of teaching. Suggest a few ways of assessing teaching and explore their strengths and weaknesses. Compare the strengths and weaknesses with those of the usual approaches to estimating research ability.

1.3 What is ‘spoonfeeding’? How does it differ from effective teaching?

1.4 Which do you prefer, lecturing or small group teaching? Why?

1.5 What are, for you, the characteristics of effective teaching? (You may find it helpful to specify various contexts when considering this question.) Jot down your list of characteristics and compare them with a few colleagues.

1.6 Three dimensions of teaching are:

Systematic .................... Slipshod

Stimulating .................. Boring

Caring .......................... Uncaring

Which of these dimensions do you consider most important?

Which do you think your students consider most important?

How do you rate yourself on each of these dimensions?

How does a class of students probably rate you?

Which do you think your students consider most important?

How do you rate yourself on each of these dimensions?

How does a class of students probably rate you?

1.7 Is teaching ever non-manipulative?

2: Studies of lecturing

The decrying of the wholesale use of lectures is probably justified. The wholesale decrying of the use of lectures is just as certainly not justified.

(Spence 1928)

It is sometimes forgotten that lectures are for the benefit of students. They have three purposes: coverage, understanding, and motivation. Without motivation attention is lost and there can be little understanding. Without information on a topic there is nothing to be understood. These purposes of conveying information, generating understanding, and stimulating interest are therefore interrelated. But in any one lecture one of these purposes is likely to be prime and thereby shape the structure and content of the lecture (see Activity 2.1).

Given the ubiquity of lecturing in universities and polytechnics— and its antiquity—it seems appropriate to spend some time exploring various studies of lecturing before considering the practical questions of how to make your lectures more effective. So in this chapter an outline of the origins of lecturing is provided followed by a model for understanding the processes of lecturing. This model is then used to provide a framework for a review of more recent studies of lecturing. The review in turn provides the basis for the subsequent chapter on the skills of lecturing.

AN HISTORICAL SKETCH

Lecturers may be traced back to the Greeks of the fifth century BC. In medieval times lectures were the most common form of teaching in both Christian and Muslim universities. The term ‘lecture’ was derived from the medieval Latin lectare, to read aloud. Lectures consisted of an oral reading of a text followed by a commentary. The method of reading aloud from a text or script is still used by some lecturers in the arts even though the conventions of written and oral language differ over time and across cultures.

In contrast, lecturers in medicine and surgery have long used the demonstration as part of the lecture. By the nineteenth century demonstrations, pictures, and blackboards were used in lectures in science as well as medicine. Today it is still the lecturers in science, engineering, and medicine who are the more active users of audio-visual aids.

Lectures are the most common method of teaching in universities throughout the world (Bligh 1980). Their continued use may be attributable in part to tradition and in part to economics. Classes of one thousand or more are not uncommon in countries which are anxious to minimize costs in higher education. In some countries the lecture may be the major source of information, and only the lecturers may have access to texts and articles in the major languages of the world.

These simple facts suggest that lectures are likely to be widely used well into the twenty-first century. Hence the importance of exploring ways of making lectures more effective as well as economical in the years ahead.

A MODEL FOR EXPLORING LECTURES

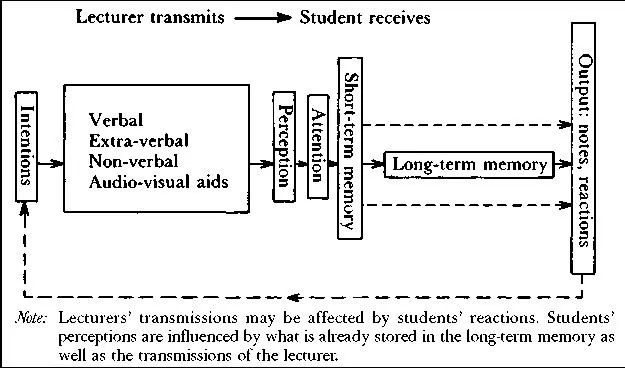

A full model of the processes of lecturing would necessarily take account of the personalities and ways of thinking of lecturers and students, their modes of communication and listening, and the nature and content of the lecture subject. All of these influence the processes of lecturing in diverse ways. Such a model is provided by Entwistle and Hounsell (1975). At its core is a simple, robust model of information processing which may be used to describe the processes of lecturing and to diagnose common errors in lecturing. The model is shown in Figure 2.1.

The key features of the process of lecturing are intentions, transmission, receipt of information, and output. Other important features are the objectives and expectations of the recipients (the students) and their intended applications and extensions of the information received. All of these features influence considerably the overall quality of the lecture as a method of teaching and learning.

Intentions

The lecturer’s intentions may be, as indicated in the introduction to this chapter, to provide coverage of a topic, to generate understanding, and to stimulate interest. Undue attention to coverage can obscure understanding. A stress on understanding may require deliberate neglect of factual detail. A stress on interest per se may lead to inadequate understanding. Of course, handouts and carefully selected readings can be used to augment coverage. Not all lectures within a course need to be concerned equally with all three goals, and other teaching methods may be used to generate understanding and interest. Consideration of the three goals of lecturing, together with a knowledge of the earlier learning of the students, are an essential constituent of lecture preparation.

Figure 2.1 Model for exploring lectures

Transmission

A lecturer sends messages verbally, extra-verbally, non-verbally, and through his or her use of audio-visual aids. The verbal messages may consist of definitions, descriptions, examples, explanations, or comments. The ‘extra-verbal’ component is the lecturer’s vocal qualities, hesitations, stumbles, errors, and use of pauses and silence. The ‘non-verbal’ component consists of his or her gestures, facial expressions, and body movements. Audio-visual messages are presented on blackboards, transparencies, slides, and audio-visual extracts. All of these types of messages may be received by the students who may sift, select, perhaps store and summarize, and note what they perceive as the important messages. A lecturer does not only transmit information: his or her extra-verbal and non-verbal cues and the quality of the audio-visual aids used may convey meanings and attitudes which highlig...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- 1: Introduction

- 2: Studies of lecturing

- 3: The skills of lecturing

- 4: Effective small group teaching

- 5: Effective laboratory teaching

- 6: Effective research and project supervision

- 7: Studies of student learning

- 8: Helping students learn

- Notes and comments

- Appendix 1: The structural phases of the tutorial encounter

- Appendix 2: Some transcripts of explanations

- Appendix 3: Suggestions for organizing workshops

- Further reading

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Effective Teaching in Higher Education by Madeleine Atkins,George Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.