![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Almost all aspects of life are engineered at the molecular level, and without understanding molecules we can only have a very sketchy understanding of life itself.

Francis Crick

Interest in alternatives to modern medicine has never been higher than it is now, and a large part of that interest revolves around the use of medicinal plants. One can purchase a wide variety of herbal products at virtually any drugstore or all-purpose retailer. Television and magazine ads proclaim the virtues of garlic, ginkgo, and ginseng. You probably know people who regularly use herbal supplements, and you may have used them yourself.

If you have picked up this book and read this far, you are probably the kind of person who has, at one time or another, wondered exactly how drinking an herbal tea can help prevent cancer, or how taking Echinacea capsules can help you beat a cold.1 Perhaps you have heard that red wine and dark chocolate can help prevent cardiovascular diseases such as heart attacks and strokes, and have wondered how such a wonderful thing is possible—though most people don’t need excuses to enjoy wine and chocolate!

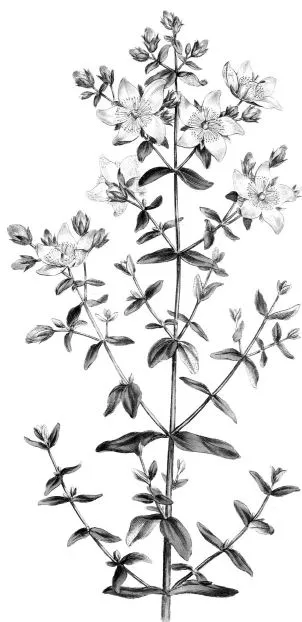

If so, then you are asking the very questions scientists ask, and how to think about these questions and understand the answers is the subject of this book. Let’s look at a common example to illustrate what I mean. Almost certainly you have heard of the plant St. John’s wort, which is recommended for the treatment of mild depression. Some of the questions you and scientists of various ilk might ask about this plant include the following:

- Does St. John’s wort actually treat depression?

- How can I identify St. John’s wort when I see it?

- What time of year should I collect the plant?

- What part of the plant should I collect?

- How much of the plant should I take, and how should I take it?

- What are the active ingredients in the plant?

- How do the active ingredients work?

- Can I overdose or poison myself by taking too much?

- Can the plant be dangerous if I’m pregnant or have high blood pressure?

Hypericum perforatum. (Source: Woodville, William. Medical Botany containing systematic and general descriptions, with pl.s of all the medicinal plants, indigenous and exotic, comprehended in the catalogues of the material medica; as published by the Royal College of Physicians of London and Edinburgh; accompanied with a circumstantial detail of their medicinal effects, and of the diseases in which they have been most successfully employed. London: printed and sold for the author by J. Phillips, 1790, Vol. 1, pl. no. 10.)

The detailed answers to these questions would require the expertise of a number of different types of scientists:

- Physicians and statisticians would determine if the plant is actually effective in treating depression.

- Botanists would help with the identification of the plant.

- Pharmacologists and chemists would help determine what time of year and what plant part to collect, as well as help the physicians with dosage issues.

- Chemists would isolate and identify the active ingredients.

- Chemists, pharmacologists, physiologists, and perhaps molecular biologists would help us figure out how it works.

- Toxicologists and physicians could take this information one step further to help us understand whether the plant might poison us or have side effects.

As you can see, with all these “-ologists,” the study of medicinal plants is a busy field (academics call it interdisciplinary). Still other scientific fields might be relevant: ethnobotanists and anthropologists to help interpret the medicinal plant knowledge of other cultures, pharmacognocists2 who would contribute in a variety of ways, and so on.

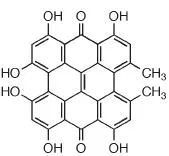

I’m certainly not prepared to discuss all of these areas, but I point them out to illustrate the nature of medicinal plant investigations. In fact, the previous questions only scratch the surface, as St. John’s wort has other interesting properties besides being an antidepressant. Regarding its antidepressant activity, however, scientists are still not completely certain which molecule is responsible. For many years it was thought that the antidepressant activity of St. John’s wort was due to a molecule called hypericin, though now other molecules are under consideration (see Figure 1.1). My point is that even after identifying hypericin (or anything else) as an active ingredient, scientists will have many more questions, such as how to analyze a plant or a pill for its hypericin content.

So this book is about questions about medicinal plants, particularly questions about what’s in them and how they work—in other words, understanding medicinal plants. It is intended for nonscientists, and I have tried to write for this audience. I have tried to maintain rigor but keep the writing accessible through careful explanation and careful choice of examples. Understanding Medicinal Plants is not the place to find information about specific herbs for particular medical conditions; many books about that topic are already available. Rather, my goal is to provide a basic knowledge of the concepts and principles needed to understand what kinds of molecules are in a medicinal plant and how they exert their influence on the human body. This may be everything you want to learn about right now, but should you eventually want to investigate a particular plant further, you will have an excellent foundation so that you can ask the right kinds of questions, and understand the answers. Although this book is about how to think about and understand medicinal plants, what you will learn can be applied to any molecules used as drugs, whether they come from a plant, a fungus, a bacterium, or even a pharmaceutical company’s laboratory.

FIGURE 1.1. Hypericin, a molecule found in St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum).

Understanding Medicinal Plants is organized as follows. In Chapter 2 we will learn to interpret the symbolism of chemical structures, such as the diagram of hypericin in Figure 1.1. These diagrams often scare people away from further reading on chemical topics, so it is well worth the time to try to demystify it. We will also talk about the naming of molecules and consider the enormous range of chemical structures that are possible.

In Chapter 3 we will look at just enough background on chemical bonding that we can begin to understand molecular properties such as the shape of a molecule. Shape turns out to be critical in understanding how a drug works on a molecular level, so we must have some appreciation of this area.

Chapter 4 is a catalog of sorts, in which examples of the different chemical families found in plants are given. This is good information to browse through at first and turn to later when more specific information on a particular family is needed (or it can be skipped entirely).

Chapter 5 looks at chemical behavior that is relevant to medicinal substances obtained from plants. We will examine acid-base behavior and such techniques as spectroscopy to see how they can be used to help isolate and identify substances from plants. Then we will turn to exploring the antioxidant properties of medicinal plants, which will bring us back to chocolate and red wine.

Chapter 6 discusses how plant drugs and toxins move through the body and act on specific molecules. We will first look at some general principles that affect how a drug is absorbed, distributed through the body, and eventually excreted in some form. We will then move to a molecular view of what happens once a drug reaches its final place of action (referred to as its target). Material covered in the earlier chapters will be essential to understanding these sections.

Finally, in Chapter 7, we will look at several case studies of medicinal plants and apply all we have learned to understand how these plants work. With the possible exception of Chapter 4, you’ll probably want to read the chapters in order.

Before we launch into this material, however, I feel I would be misleading you if I didn’t mention something about my beliefs about medicinal plants, because they color my approach to the topic. The word beliefs has a religious air about it and, indeed, many people believe that medicinal plants have some special, mystical properties because they are natural, or organic, or God given. For similar reasons, some folks reject anything considered a “chemical” because they believe them to be fundamentally bad, or they reject mainstream medicines because they are synthetic. Indeed, we have much to learn about medicinal plants; in some cases whole herbs, as opposed to extracts or purified materials, are better. But is also true that nature contains many, many toxic substances, so we should not label plants and natural, herbal treatments as superior in all cases. Like it or not, virtually everything in the world is a chemical or is composed of chemicals. In fact, the entire point of this book is to help you think about these kinds of issues and use your knowledge effectively.

The eminent pharmacognocist Varro Tyler liked to point out that a great percentage of conventional modern medicines actually come from plants, and he argued convincingly that “rational herbal medicine is conventional medicine” (Robbers and Tyler, p. 15). In other words, while many people consider herbs to be alternative medicine, they really are quite conventional when you examine history and current practice. Tyler also identified ten criteria that are characteristic of what he called “paraherbalism,” which he considered a pseudoscience. If the difference between rational herbalism and paraherbalism interests you, and I hope it does, be certain to see the introduction to his book Herbs of Choice for more information (details are given in the suggested reading).

I’d like to briefly emphasize one other concept that should be kept in mind at all times. The art of healing is complex and multifaceted. In any culture, healing practices are part psychological and symbolic, part physiological. Psychological and cultural influences on healing are fascinating topics and important to understanding the use of medicinal plants, both historic and modern. Much has been written on these topics, and I hope you have or will read some of the fine works available. In this book, however, the focus is on the physiological actions of medicinal plants. My hope for you, the reader, is that by learning some of the chemistry and pharmacology of medicinal plants, you can move toward a deeper understanding of how to evaluate what you hear about medicinal plants.

SUGGESTED READING

Balick, M. J. and Cox, P. A. (1997). Plants, people, and culture: The science of ethnobotany. New York: Scientific American Library. A very readable description about how plants affect culture, and how we Westerners “discover” medicinal plants.

Blumenthal, M., Goldberg, A. and Brinkmann, J. (eds.) (2000). Herbal medicine: Expanded Commission E monographs. Boston: Integrative Medicine Communications. This is an excellent source to begin digging into individual herbs on a more technical level.

Robbers, J. E. and Tyler, V. E. (1999). Tyler’s herbs of choice: The therapeutic use of phytomedicinals. Binghamton, NY: The Haworth Herbal Press. One of the best books about what herbs to use for what conditions; also discusses paraherbalism and rational herbalism.

Sumner, J. (2000). The natural history of medicinal plants. Portland, OR: Timber Press. A potential companion to this book which presents a botanical/ecological perspective.

![]()

Chapter 2

Interpreting the Symbolism of Chemical Structures, or, Finding Your Way Around a Molecule

It is a pity that most people think a scientist is a specialized person in a special situation, like a lawyer or a diplomat. To practice law, you must be admitted to the bar. To practice diplomacy, you must be admitted to the Department of State. To practice science, you need only curiosity, patience, thoughtfulness, and time.

A. Holden and P. Morrison, 1982

Crystals and Crystal Growing, p. 11

Many people find chemistry intimidating, and much of that feeling comes from the extensive symbolism used in the field. By symbolism I mean the formulas and structures and everything conceptual that is implied by them (there’s a lot of symbolic math in chemistry too, but we won’t worry about that)....