- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The time has come to challenge many of the age-old assumptions about schools and school learning. In this timely book leading thinkers from around the world offer a different vision of what schools are for. They suggest new ways of thinking about citizenship, lifelong learning and the role of schools in democratic societies. They question many of the tenets of school effectiveness studies which have been so influential in shaping policy, but are essentially backward looking and premised on school structures as we have known them. Each chapter confronts some of the myths of schooling we have cherished for too long and asks us to think again and to do schools differently. Chapters include:

* Democratic learning and school effectiveness

* Learning democracy in an age of mangerial accountability

* Democratic leadership for school improvement in challenging contexts.

This book will be of particular interest to anyone involved in school improvement and effectiveness, including academics and researchers in this field of study. Headteachers and LEA advisers will also find this book a useful resource.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Democratic Learning by John MacBeath,Lejf Moos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Educación general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Democratic learning and school effectiveness

Are they by any chance related?

John MacBeath

Nearly three decades have passed since the first study of school effects. The impact of the hundreds of studies conducted in those intervening years has been felt at the level of government, local authority, school and classroom. School effectiveness research has fundamentally changed the way we think, introduced a new lexicon of terms and ensured that, for good or ill, schools will never be the same again. But what has that movement contributed to our understanding of democratic learning? It is a highly pertinent question for the future of effectiveness and improvement research. It is time to remind ourselves of what schools are for and what they may become—with a little help from their critical friends.

Democracy—an undisputed good?

Democracy. It is an assumed good although one to which not everyone would subscribe, at least not without a critical testing of the meanings carried within that term (Tooley 2000). Democracy is a value judgement about the way in which a society, or coalition of societies, should be organised, and so before proceeding further it requires a working definition. The following is one among many but is a helpful one in its juxtaposition of individual rights and moral/social reciprocity: ‘A democratic society, or a participative democracy…is one in which its members are empowered to make decisions and policies concerning themselves and their society but where such decisions are constrained by principles of nonrepression and nondiscrimination’ (Pearson 1992:84). While this is a notion which most teachers, and most people in the school effectiveness movement, would be happy to endorse, a more contested assertion is that democracy is relevant to the nature of institutions and, in particular, to schools. After all, schools can cover a 60- year age range and the whole spectrum of abilities, intelligences and moralities. Teachers, there by choice and profession, bring experience and expertise while children are, it is widely assumed, there to learn from their elders and betters.

Yet, it may argued, without a commitment to democratic processes how well can a school serve the purposes of a democratic society? The two key constituents of Pearson's definition of democracy offer a most relevant litmus test of school culture:

- the personal authority that we allow to children and young people to take decisions that affect them;

- the obligations that we place on them, and ourselves as educators, to respect the rights of others—the moral imperative.

Geert Hofstede's work over a couple of decades has focused on both national and institutional cultures using four dimensions which attest to the democratic, or undemocratic, nature of a society or organisation (Hofstede 1980). These are:

- power distance: demand for egalitarianism as against acceptance of the unequal distribution of power;

- individualism-collectivism: interdependent roles and obligations to the group as against self-sufficiency;

- masculinity-femininity: endorsement of modesty, compromise and cooperative success as against competition and aggressive success;

- uncertainty avoidance: tolerating ambiguity as against preferring rules and set procedures.

Against these criteria the Scandinavian countries have performed significantly well and it is to them that we have tended to look as democracy's natural home, their schools being microcosms of their cultures. There is a story, perhaps apocryphal, about the invasion of France by the Danes. When they arrived in Normandy they were asked what they wanted and they replied:

‘We come from Denmark and we want to conquer France.’

‘Who is your chief?’

‘We have no chief. We all have equal authority.’

‘Who is your chief?’

‘We have no chief. We all have equal authority.’

(Zeldin 1996:172)

Later they were to set up a community in Iceland, described by Zeldin as ‘one of the most astonishing republics ever known, a sort of democracy reconciling the fear of losing their self-respect—which obeying a king would imply—with respect for others’ (p. 172).

More recently, in a study of equity (Benadusi 2001), Sweden emerges as one of the very few countries of the world where the gap between the most and least well off has not increased and, if anything, has diminished slightly. Respect for self and others is embodied in the Swedish policy paper A School for All (Ministry for Education and Science 2002). The four basic characteristics of the democratic school are defined as:

- relationships and how we treat and value each other;

- the equal value of all people, irrespective of gender and background;

- respect and understanding of differences between people;

- rights and responsibilities in a democratic society.

Realising these values within a school has, however, to be understood not only within the local and national contexts but within the global context in which young people are expected to value democracy and to become world citizens. There is, however, widespread evidence (e.g. Kerr et al. 2001) that young people are sceptical of political democracy and disengaged from the political process, an unsurprising finding given a general decline in civic trust among the population at large in most advanced economies

(Pharr and Putnam 2000).

Evidence of a widespread erosion of public trust in representative democracy is not hard to seek. In the UK in 1997 the Conservative government left under a cloud of ‘sleaze’ and corruption, making way for a new Labour government who have perpetuated and even exacerbated the slide in public confidence, reaching a new low in December 2001 with the resignation of the government standards watchdog. In the USA, Pharr and Putnam (2000) have, through successive surveys of public opinion, traced the progressive decline of civic trust. For example, in 1964 under the Johnson administration only 29 per cent of Americans agreed that ‘the government is pretty much run by a few big interests looking out for themselves’. By 1984 this figure had risen to 55 per cent and by 1998, to 63 per cent. Countries for which there are equivalent types of data over time (e.g. Sweden and Germany) tell a similar story. At the end of 2001 a right of centre Danish government came to power, riding the momentum of September 11, an event that was proclaimed widely as ‘changing the world’. It has, in many significant ways. It has led to a fundamental review of what we understand by democracy. It has recast the debate on multiculturalism. It has had a potentially massive re-educative potential with regard to Islamic cultures and beliefs and forced us to rethink the interface between religions and politics. It could of itself provide a focus for a whole school curriculum. Writing, with some presence, Castells (1996:3) noted that:

Political systems are engulfed in a structural crisis of legitimacy, periodically wrecked by scandals, essentially dependent on media coverage and personalized leadership, and increasingly isolated from the citizenry. Social movements tend to be fragmented, localistic, single-issue orientated, and ephemeral, either retrenched in their inner worlds, or flaring up for just an instant around a media symbol. In such a world of uncontrolled, confusing change people tend to regroup around primary identities.

Teaching about democracy cannot be, therefore, some theoretical or abstract notion. It can only be grasped when we are mindful of its immediate and long-term relevance to children's, young people's, teachers’ and parents’ experience of the world as they know it. Teaching for democracy is a problematic notion in its assumptions about the world ‘out there’ and the world ‘in here’, since, for some children, school may be a more democratic place than the society in which they find themselves thereafter, although the obverse may also be true.

For school effectiveness, whether as a research concept, a policy priority or a school goal, such insights are of critical importance. Given that the central measure of a school's success is student achievement, it makes little sense to measure this without an understanding of what achievements mean in their local, national and international contexts. We are all players (or onlookers) in the ‘network society’ as so brilliantly portrayed by Manuel Castells (1996, 1999). He identifies three key ideas fundamental to our understanding of democracy in and out of school:

- informational capitalism

- social exclusion

- perverse integration.

Every country of our world is affected profoundly, economically and socially, by the new capitalism—the worldwide trade in information. Access to information and the ability to discriminate and exploit it for personal benefit is what increasingly separates the knowledge haves from the knowledge have-nots. And year on year the gap widens. This is closely tied to social exclusion. As has been shown (Martin 1997; Putnam 1999), social exclusion recreates itself from generation to generation and is closely associated with chronic illness, premature death and suicide. Although rates of suicide among older age groups are declining it is rising rapidly among the young. Young people spend more and more time alone, in homes, families, surrogate families or institutions with few supportive social networks. For the less passive and victimised, the route back into the economy is through a shadow economy of borderline legality and criminal activity—a route back which Castells terms ‘perverse integration’.

Putnam (1999) claims that Americans, in all age groups, are now ‘bowling alone’—his metaphorical index of social capital. Could bowling together be correlated with students’ success at school? Could measured student achievement be associated with communities in which there are social networks bringing people together across age groups? David Berliner (2001) argues that there is a direct correlation between student achievement and social capital (defined by inclusive measures such as belonging to formal and informal organisations—churches, associations, unions, clubs—communities of common interest). It is a provocative argument and brings us to the school effectiveness agenda because it is James Coleman that we regard as the originator of both school effects research and the concept of social capital, two inseparably linked concepts.

Democracy, school effectiveness and improvement

The school effectiveness story begins in the reign of the only US president to have been a schoolteacher, and in retrospect one of the most democratic of all American leaders. Lyndon B.Johnson presided over the War on Poverty, the Great Society reforms and, in the first year of his presidency, introduced the Civil Rights Act (1964) against strong resistance. His administration commissioned the Coleman et al. (1966) research into equality of opportunity, a landmark study the importance of which cannot be overestimated. Despite much criticism of the methodology, flawed by comparison with many subsequent studies, it was the first time that such data on inequality, on schools and school performance had been collected, data which was to fundamentally change, perhaps forever, the way in which people viewed school education.

The central concern of the Coleman study, and a few years later the Christopher Jencks report (Jencks et al. 1972), was with the role of schooling in redistributive equality, and its power to make a difference to the life chances of children. Their concern was with schooling as an educational agency capable of reshuffling the social pack, opening up opportunity to learn and to succeed in and beyond school. It is significant that both the Coleman and Jencks studies were situated in a period in which systematic data collection was in its infancy. Commenting on the data vacuum, Orfield and Eaton (1996:166) write:

The United States did not collect such data through most of its history. Poverty was not defined as a basic category in the U.S. data systems until the mid- 1960s… Officials commonly denied that racial and ethnic data were needed, argued that they would be used for discriminatory purposes and that publishing them would further stigmatise the populations because such data would disclose sharply unequal outcomes. The basic idea was that it would be better off not knowing.

The data vacuum was filled by a radical, and often highly subjective, critique of schooling as an educational agency, as the book titles alone from that era demonstrate: Compulsory Miseducation (Goodman 1971), Death at an Early Age (Kozol 1968) School is Dead (Reimer 1971), Deschooling Society (Illich 1971) The Underachieving School (Holt 1976) and Crisis in the Classroom (Silberman 1973), while in Europe Torsten Husen, Hartman von Hentig and Ian Lister were all penning their own devastating critiques of schooling.

Much of this literature was concerned with what Kozol was later, in 1998, to describe as ‘savage inequalities’ but the attack was on a broader front, on the nature of the schooling experience, on the very competence of schools to be genuinely ‘educational’. Illich was to describe an institution as ‘an organisation designed to frustrate its own goals’ and to coin the much reiterated maxim that ‘school is a gap in your education’ (Illich 1971).

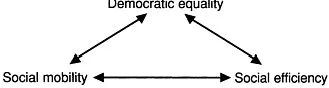

The setting for the Coleman and subsequent studies, while focused centrally on equality, has to be understood within the wider current of ideas and socioeconomic movements. Labaree (1997) has recently identified three predominant and competing models of schooling's purpose, each of which (democratic equality, social mobility and social efficiency) has been to the fore in different periods of educational ideology in the USA and which continue to coexist in precarious balance. They are, perhaps, equally relevant to other countries of the world (see Figure 1.1).

- Democratic equality conceives of schools as helping to create democratic values through teaching about democracy, developing

Figure 1.1 Labaree's (1999) competing models

the skills and attitudes of democratic citizenship and treating equality as a valued goal of schooling.

- The social mobility goal is seen as offering students, and their parents, a vehicle for acquiring the markers that will give access to better jobs and higher salaries. Wise choice of schools brings competitive advantage which may give the individual that crucial edge ‘out there’. School learning is a means to an end rather than an end in itself. This model assumes knowledge to be a private commodity and regulates it through the currency of grades and credentials. Knowledge is measured in performance and performance is necessarily normative—relative to others.

- Social efficiency sees schools and higher education as perfo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contributors

- Introduction

- 1: Democratic learning and school effectiveness Are they by any chance related?

- 2: Reforming for democratic schooling Learning for the future not yearning for the past

- 3: Democratic values, democratic schools Reflections in an international context1

- 4: Learning democracy by sharing power The student role in effectiveness and improvement

- 5: Children's participation in a democratic learning environment

- 6: The darker side of democracy A visual approach to democratising teaching and learning

- 7: Democratic leadership in an age of managerial accountability

- 8: Democratic leadership for school improvement in challenging contexts

- 9: Learning in a knowledge society The democratic dimension

- Conclusion Reflections on democracy and school effectiveness