- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Through a detailed re-reading of Saussures's work in the light of contemporary developments in the human, life and physical sciences, Paul Thibault provides us with the means to redefine and refocus our theories of social meaning-making. Saussure's theory of language is generally considered to be a formal theory of abstract sign-types and sign-systems, separate from our individual and social practices of making meaning. In this challenging book, Thibault presents a different view of Saussure. Paying close attention to the original texts, including the Cours de Linguistic Generale he demonstrates that Saussure was centrally concerned with trying to formulate a theory of how meanings are made.Re-reading Saussure does more than simply engage with Saussure's theory in a new and up-to-date way, however. In addition to demonstrating the continuing viability of Saussure's thinking through a range of examples, it makes an important intervention in contemporary linguistic and semiotic debate.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Re-reading Saussure by Paul J. Thibault in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Constructing a science of

signs

Chapter 1

Defining the object of study

1 STAKING OUT A SCIENCE OF THE LINGUISTIC SIGN

Commentators such as Jonathan Culler (1976) and Terence Hawkes (1977) have tended to emphasize the Copernican revolution, as Roy Harris (in Saussure 1983: ix) puts it, which was inaugurated with the posthumous publication of Saussure's CLG. Saussure's achievement, according to this view, lies in his systematic elaboration of a general science of signs, or a semiology. In CLG these principles are, of course, elaborated with respect to language, which Saussure envisaged as just one part of a more comprehensive study of ‘the life of signs in social life’ (CLG: 33; emphasis in original). Thus, Saussure stakes out the citizens’ rights of this future science of semiology right from the outset. Further, Saussure does not view this science of semiology as an autonomous science. ‘It would’, he claims, ‘form part of social psychology, and consequently of general psychology’ (CLG: 33). I shall return to this last point in Chapter 2, section 4.

It is doubtful that Saussure intends the terms ‘social psychology’ and ‘psychology’ to mean exactly what we understand by these notions in their contemporary sense. Saussure does not take this point any further. Instead, he undertakes a quite precise division of labour. He leaves it up to the psychologist ‘to determine the exact place of semiology’ (CLG: 33) in the overall field of human knowledge. The more specific and delimited task of the linguist, Saussure continues, ‘is to define what it is that makes the language system [la langue] a special type of system within the totality of semiological facts’ (CLG: 33). In making this claim, Saussure effects an important strategic move; it is a move which is both political and theoretical in its implications. Linguistics becomes constituted as an ‘autonomous’ realm of scientific enquiry at the very moment when language is constituted as an object of scientific enquiry in its own right:

Why is it that semiology is not yet recognized as an autonomous science, having like all the others its own object? This brings one full circle: on the one hand, there is nothing more suitable than the language system for allowing the nature of the semiological problem to be understood; but, in order to pose it in an appropriate way, it has almost always been approached as a function of something else, from other points of view.There is first of all the superficial conception of the general public: it sees the language system as nothing more than a nomenclature (see p. 97), which suppresses all research on its true nature.(CLG: 34)

Saussure is intent on shifting the study of language from the purely instrumental basis which had prevailed, and as a result of which language had been a means for studying something else, to language as an object of systematic enquiry in its own right (Chapter 2, section 6).

Many commentators have taken this to mean that for Saussure the concrete social and historical production and use of signs is split from the science of semiology which he envisages. However, Wlad Godzich (1984: 19) has suggested that Saussure's notion of social psychology may constitute the locus of a renovated science of signs in social life. In this book, I shall attempt to demonstrate that Saussure's conception of the sign is entirely compatible with such a project. It is also an essential starting point for a theory of signs in social life. In the next section, I shall discuss two models of scientific enquiry which have hitherto influenced our understanding of Saussure.

2 TWO THEORETICAL MODELS FOR READING CLG

The commentators whom I named above reflect the more recent structuralist reading of CLG. Structuralism developed as a full-fledged movement in the human sciences, first in France, then elsewhere, in the period which runs from the 1950s to the 1970s (Thibault, in press a). Its intellectual and historical roots go back to the Russian formalists, who were active in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s. This entailed a specific reading of CLG. Further, the general principles which Saussure elaborated for language were extended beyond language to a wide variety of other signifying systems: kinship, the mass media, popular culture, gastronomic codes, fashion, narrative and so on. This also entailed a particular conception of ‘theory’. Taking a particular reading of Saussure's concept of langue as their model, the structuralists sought a conceptual framework in which the mechanisms which are postulated as lying ‘behind’ and causing the observed phenomenon might be studied. Such generative mechanisms would then constitute the explanation of the phenomenon.

A theory, so defined, assumes an ontology of the causal mechanisms which underlie and generate the observed phenomenon. The ontological basis of theory, in this sense, resides in the notion that the language system (langue) defines the general conditions of possibility of human subjectivity and experience. This presupposes, as Ian Hunter (1984) has argued, that a continuous and totalizing conception of human experience is founded on the general conditions of possibility afforded by langue.

The structuralist reading of Saussure made this ontology very much its own. Structuralism, however, takes the matter still further. The structuralists claim that signifying systems and their principles of organization represent the very conditions of possibility of the ways of perceiving, experiencing and acting of the individual members of a given social or cultural order. Lévi-Strauss (1972) quite explicitly locates these systems and rules in the pre-given and universal structures of the human mind. Consequently, the constructive role of individual and social activity is marginalized. In structuralism, there is no account of signs-in-use. Structuralism remains a formal theory of abstract and decontextualized systems of signs. It posits essentially a priori structures and categories of mind very much after the fashion of Immanuel Kant (1970 [1781]). These are categories which exist prior to individual human experience and which allow individuals both to recognize and to categorize the world, as well as to impose a rationality upon it.

There is also another sense in which CLG can be read as a theory of the language system. This has received less attention from the structuralists, although it has been central in the development of the various structural-functional theories of language which CLG also foreshadowed. In this second sense, a theory is an open set of necessarily related propositions. These serve to express the relationships among the various concepts of the theory. From this point of view, Saussure, in an admittedly programmatic and incomplete way, maps out a blueprint for the structural-functional description of the internal design features of a given language system, or its grammar. He seeks to interpret the basic constituent units, their interrelationships and their functional values in the grammar of a given language.

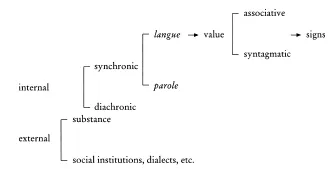

3 INTERNAL VERSUS EXTERNAL LINGUISTICS

Saussure's initial problem is really very simple: what methods must the linguist use and what analytical decisions must he or she take in order to separate language from other related phenomena in the process of studying the internal design features of language itself? Instead of using language as a means or instrument for investigating non-linguistic phenomena, this requires that language and its internal systems of relations themselves become the object of study (section 1 above). It is sometimes mistakenly thought that Saussure proposes a static and closed model of language. But this is to mistake an essentially methodological decision about how to delimit the study of the language system with Saussure's comprehensive knowledge of historical, geographical and dialectal factors, which are ever present in CLG. For example, Saussure, in terms not dissimilar to the ‘centripetal’ and ‘centrifugal’ tendencies which Mikhail Bakhtin (1981 [1975]) observed in the language practices of a community, wrote: ‘In the whole of the human masses two forces simultaneously act unceasingly and in opposite ways: on the one hand, the particularistic spirit, the "parochial spirit"; on the other, the force of "intercourse", which creates communication among men’ (CLG: 281).

Saussure sets about defining this new science in terms of a basic distinction between an ‘internal’ ‘linguistics of the language system [langue]’, and an ‘external’ ‘linguistics of speech [parole]’ (CLG: 36–9). He gives theoretical prominence to the first of these as a way of delimiting the object of study. In Saussure's view, the language system is a system of terms related by the purely negatively defined differences that distinguish any given term from the others in the same system (Chapter 3, section 3). The primary task of the linguist is to study the internal principles of organization of the language system, so defined. ‘External’ linguistics, which is seen by Saussure as ‘secondary’ to the more ‘essential’ internal linguistics (CLG: 37), is concerned, on the other hand, with individual and social uses of language. These include, as Saussure points out, the study of language in relation to: (1) its historical development; (2) social institutions such as church and school; (3) the literary development of a language; and (4) political history (CLG: 41).

Now, the dichotomous view of the relationship between the two components of this distinction remains to this day the dominant reading of Saussure. Moreover, linguists and semioticians who have taken up this reading have tended to assume that Saussure's distinction between an ‘internal’ linguistics of langue and an ‘external’ linguistics of parole amounts to a description of the concrete reality of language. In actual fact, the distinction between langue and parole belongs to a theory of linguistics. It is not inherent in the concrete reality of language (Coseriu 1981: 18). I think this is a serious misreading of Saussure, which has given rise to a confusion between methodology, on the one hand, and ontology, on the other. A careful reading of Saussure does not necessarily lead to the rigid set of dichotomies which have predominated in subsequent thinking about these issues. One of the purposes of this book is to propose an alternative reading of this relationship.

Saussure is very clear about the methodological problem which confronts him. Here he is at the very outset of CLG attempting to come to grips with the problem of defining the language system (langue) as the object of study:

Language [langage] at each instant implicates at the same time an established system and an evolution; at each moment, it is an institution in the present and a product of the past. It seems at first glance very simple to distinguish between this system and its history, between what it is and what it was; in reality, the relationship which unites these two things is so close that it is difficult to separate them.(CLG: 24; my emphasis)

The separating of the two is not in the ‘reality’ of the concrete and living language (langage), but in the methodological perspective which the linguist adopts in order to analyse this. Saussure does not ontologically split language (langage) in two. Instead, linguistic theory, as Saussure defines it, makes a methodological and, hence, epistemological distinction between langue and parole. This is abundantly clear in the opening chapter of the later discussion dedicated to synchronic linguistics:

delimitation in time is not the only difficulty that we encounter in the definition of a state of the language system [état de langue]; the same problem poses itself in regard to space. In brief, the notion of a state of the language system can only be approximate. In static linguistics, as in the majority of the sciences, no demonstration is possible without a conventional simplification of the data.(CLG: 143; my emphasis)

The process nouns delimitation, demonstration and conventional simplification in this quote amply suggest that Saussure is not talking about language per se. Instead, he is referring to the theoretical and descriptive activities which the linguist performs in the process of transforming — cf. delimiting’, approximating’, ‘demonstrating’ and ‘simplifying’ — the data into terms compatible with his science of a ‘static linguistics’. Figure 1.1 extends and develops the diagram whereby Saussure himself proposes ‘a rational form which linguistic studies must take’ (CLG: 139).

Saussure analytically separates langage (‘the [Japanese, English or French, etc.] language’) into two components: (1) langue, or the language system, which is the resource systems that language users draw on and deploy in order to make meanings in specific contexts; and (2) parole, or ‘speech’, which is ‘the sum of what people say’, comprising ‘(a) individual combinations, dependent on the will of the person who speaks, and (b) acts of

Figure 1.1 Defining the domain of the object of study; internal and external linguistics

phonation, which are equally voluntary, necessary for the execution of these combinations’ (CLG: 38; Chapter 2, section 3). Saussure claims that langue is ‘social in its essence and independent of the individual’ (CLG: 37). Does this mean, then, that parole is for Saussure purely individual, random, subjective and voluntaristic? Or is parole, on the other hand, patterned and socially constrained? Generally speaking, parole has been interpreted as being a mere ‘rag-bag’, as Holdcroft (1991: 52) puts it, of random and accidental features. I shall develop alternative arguments in Chapter 5.

According to some scholars, these distinctions derive from the sociological theory of Emile Durkheim. In The Rules of Sociological Method (1982 [1902]), Durkheim proposes a ‘morphological’ definition of the ‘social fact’. It has been claimed that this anticipates the concept of langue as a purportedly anonymous and coercive s...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I Constructing a science of signs

- Part II Langue as social-semiological system

- Part III Langue and parole: re-articulating the links

- Part IV Linguistic value

- Part V Sign and signification

- Part VI Sign, discourse and social meaning-making

- Appendix I Appendix

- Reference

- Name index

- Subject index