- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Early Modern Italy is a fascinating survey of society in Italy from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries - the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. Covering the whole of the Peninsula from the Venetian Republic, to Florence, through to Naples it shows how the huge economic, cultural and social divides of the period still affect the stability of present day united Italy.

This is an essential guide to one of the most vibrant yet tempestuous periods of Italian history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Early Modern Italy by Christopher Black in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia europea. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

StoriaSubtopic

Storia europea

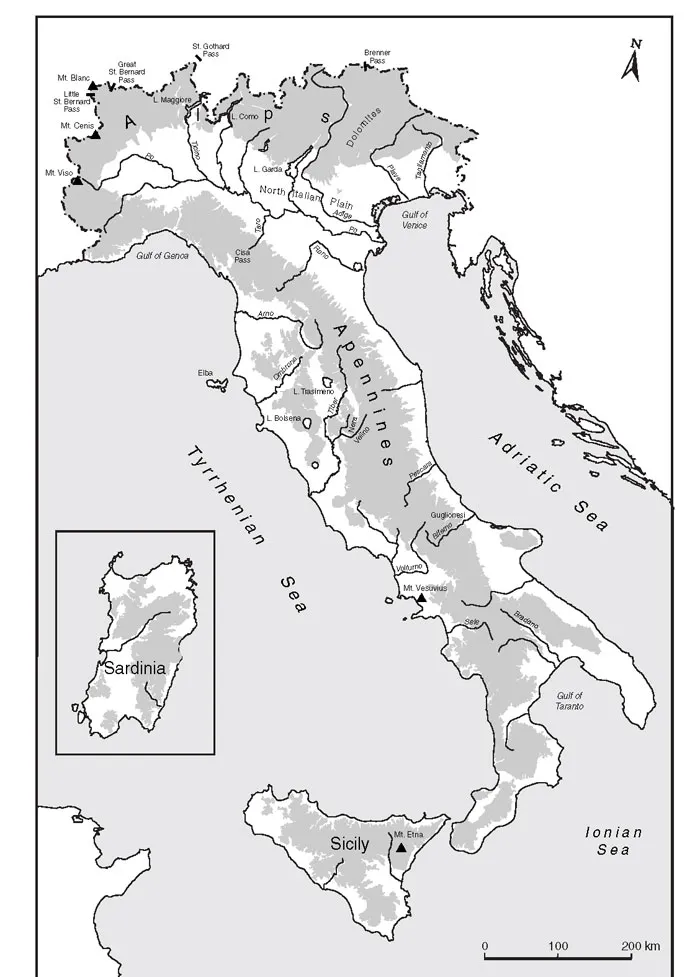

Map 1 Physical Italy.

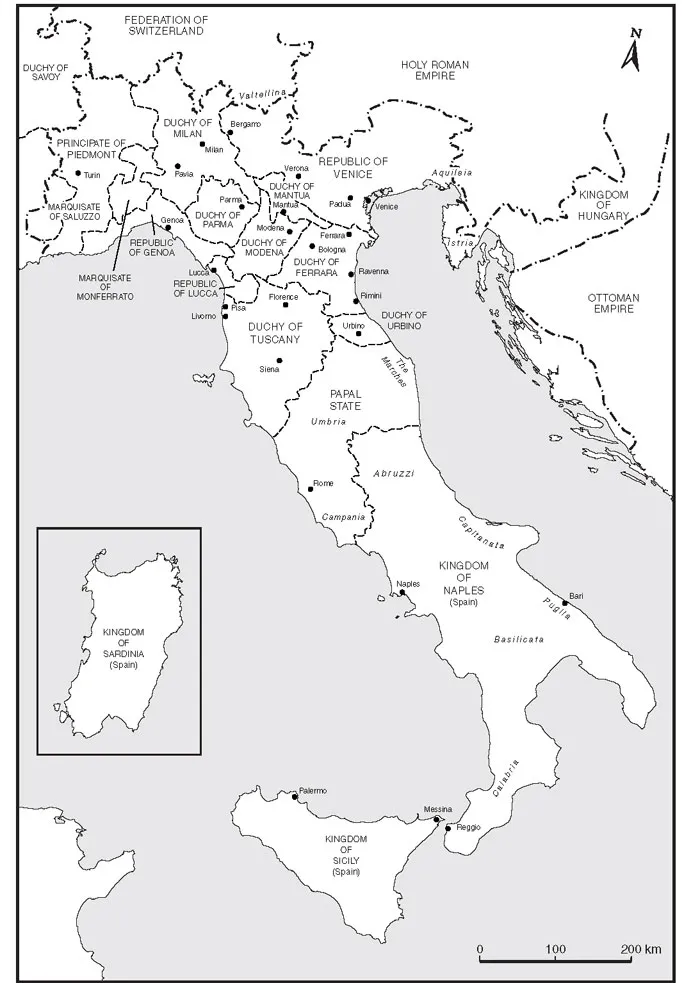

Map 2 The Italian States, 1559.

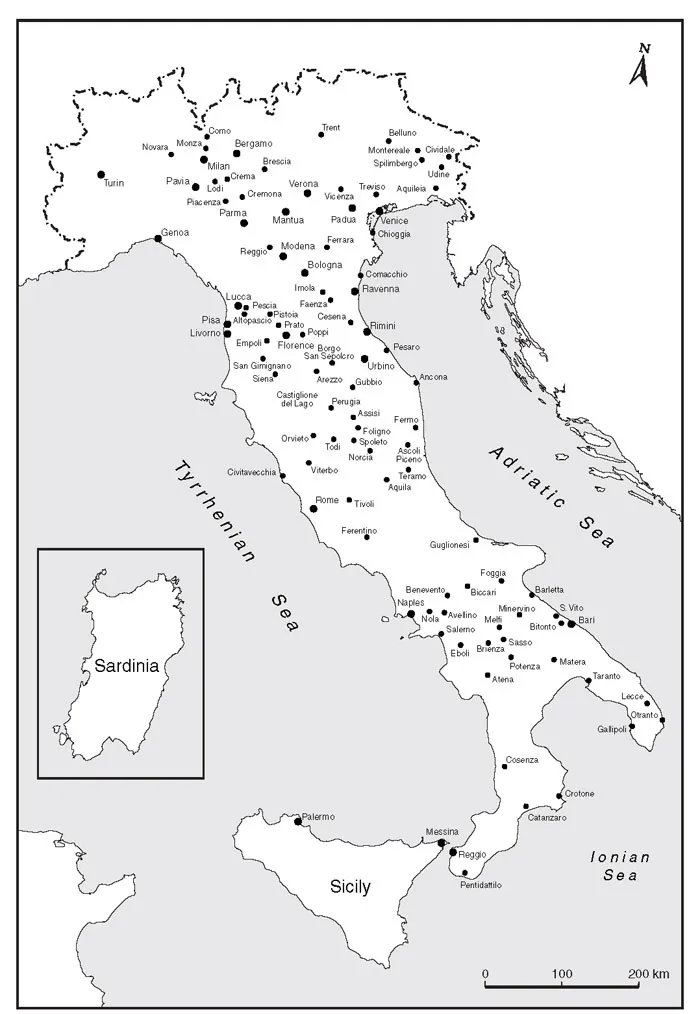

Map 3 Italian cities and towns.

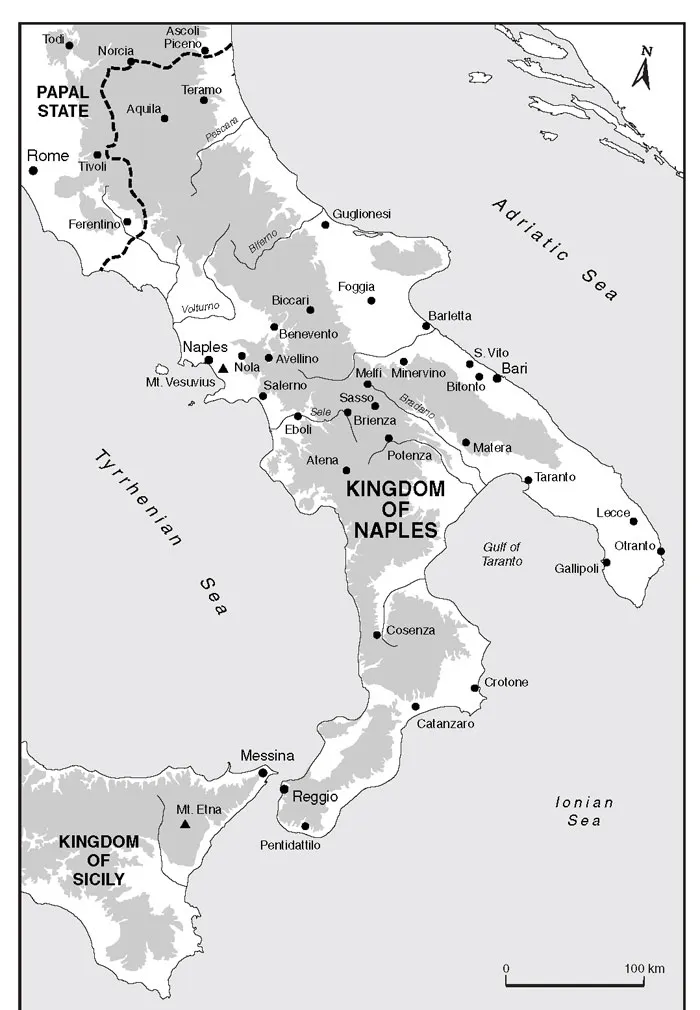

Map 4 The Kingdom of Naples.

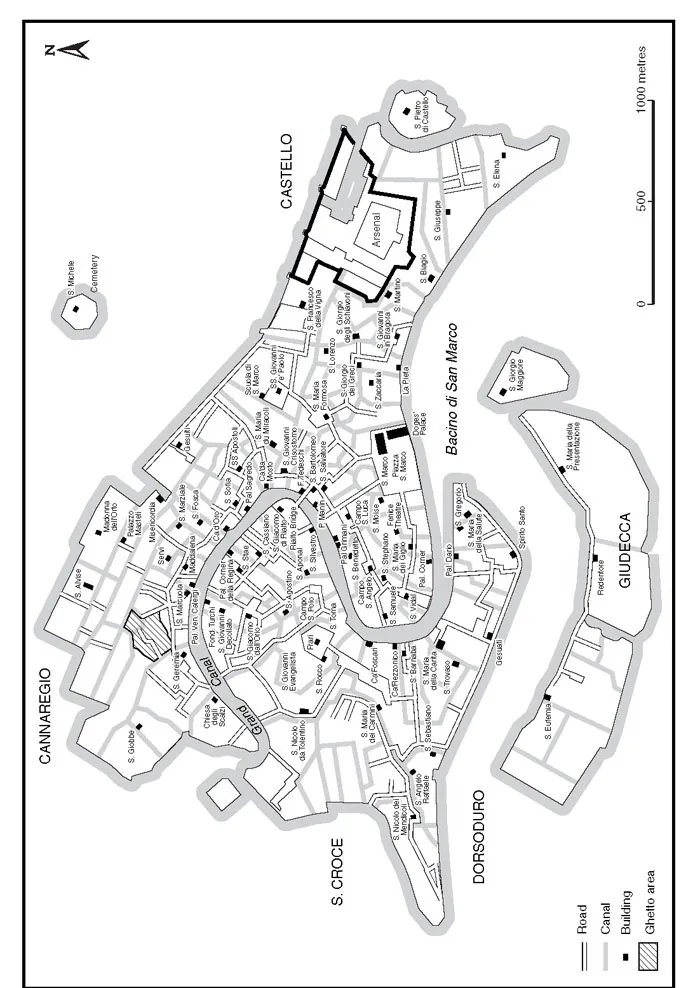

Map 5 The city of Venice.

1

DISUNITED ITALY

Unity and disunity

Italy in the early modern period, roughly from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, Renaissance to the Enlightenment, is not normally seen as a coherent unit. Politically it was subdivided into different kinds of States, as maps 2 and 4 indicate.1 In the nineteenth century the dominant European statesman Prince Metternich notoriously stressed, when resisting nationalism, that Italy was merely a ‘geographical expression’. It remained without political unity until 1870–71 when Rome itself was finally absorbed into United Italy, and became the capital. Even then the political state of Italy might arguably be seen as devoid of real Italian national feeling through the peninsula. It has been argued that there was a deep North–South divide within Italy, based on mutual ignorance, distrust or envy, that had made political unity of the whole geographical expression even more difficult for the few who desired it; and rendered such full unity unpalatable even to the majority of those who understood what was taking place in the 1850s to 1870s. Bitter civil war scarred the South in the 1860s.

Though the new Italy was supposedly based on linguistic nationalism and the sense of a common Roman classical past, very few spoke a common Italian language, and even fewer could have felt that they were heirs to a proud Roman past. Estimates of those who spoke ‘Italian’ at Unification vary from about 2.5 per cent to 12 per cent. The area is still possibly the most diverse linguistically in Europe. There are debates over definitions of ‘language’ and ‘dialect’, whether Italy has and had many languages (Florentine, Venetian, Sicilian, Calabrian, etc), or many dialects, derived from a common Latin origin. Some treat Ladino and Friulian as dialects, rather than separate languages. There are and were areas within Italy where other languages were spoken; southern areas where the common language was Greek or Albanian, and northern borders where French, German, Slavic languages and mixed dialects prevailed. All these languages had contaminated, infiltrated, or enriched (depending on your point of view) the speech and writing of wider regions.

These comments on linguistic disunity can be treated in various ways, and be misleading. Modern expectations of those living in monolingual societies, and wanting a common international language for instant communication, may exaggerate 1 the difficulties of the past scene of linguistic diversity and mutual incomprehension. In our period the educated elites had the common language of Latin useable through the peninsula and further afield till the eighteenth century at least. Furthermore the sixteenth century saw, after some intense and interesting debate, the recognition of an educated Italian vernacular language, based on Florentine and Tuscan; though thanks to a leading Venetian writer, Cardinal Pietro Bembo, it was old-fashioned Tuscan literary grammar, syntax and spelling rather than contemporary sixteenth-century discourse. The spread of printing ensured a ubiquity of this more or less agreed Italian, whether the presses were in Florence, Milan, Rome, Naples or Venice; though the Venetian presses also printed literary texts in Venetian dialect. Public notices, legal, ecclesiastical, charitable, were printed in this Italian; one has to assume that in the market square or church porch there was the odd person able and ready to read out, translate into another dialect and explain them. Thereby, a knowledge of some standard Italian percolated through society, to be heard and spoken, but not read. As will be suggested at various points, the numbers of people from all levels of society who moved about Italy, between dialect areas, were considerable and many must have learned to cope with verbal communication quickly. A Calabrian arriving in Naples or Rome, a Roman, Florentine or Friulian reaching Venice, would initially find most speech around incomprehensible; by prior design or chance they might find a family or group from their own dialect and ‘national’ background. But they must have soon become comprehensibly involved with other languages.

Court records such as those of the Venetian Inquisition, the Roman Governor’s criminal court, or the Bologna Torrone, suggest members of the lower orders from a variety of regions adequately communicated verbally – not just with knife and fist. Similar records throughout Italy put the evidence of the accused or witnesses in more or less standard Italian, though a few phrases and words might be in a local dialect. This was true even in the South. David Gentilcore, who has considerable experience dealing with investigative records, has found only one extensive record in a regional dialect (Calabrian). Some dialect comes through when a local scribe for the feudal court in the Calabrian village of Pentidattilo records a complex trial concerning murder and abortion in 1710; his record involved a complex translation procedure.2 There are implications for those seeking to comprehend what ‘voice’ is coming through such records. But in this context I would stress peoples’ abilities to overcome linguistic disunity, with the help of notaries and lesser scribes as communicators in society. Many travelled widely through their home region, towns and countryside, and were able to communicate, trade and intermarry.

Given the disunity even at the time of Unification, should we not confine ourselves – especially given the richness of local history – to reasonably coherent and cohesive sub-areas; based on old states, dynastic conglomerations or regional economies? One response is to say that because there is a modern united Italy – for good or ill, and under whatever threats over recent years – there should be pre-modern studies that illuminate the background of that same area, precisely explaining the diversity, conflicts and near incompatibilities from the past that still affect the stability and fragility of the present. Another response, especially from non-Italians, is that a perpetuated concentration on the famous sub-divisions – of Florence/Tuscany, the old Papal State, the Venetian Republic, or the Kingdom of Naples – distorts historical understanding by down-playing comparative analysis with near neighbours. The regional specialisation of many Italian historians, and fear of their professional rivals, means they would rather prove their breadth of learning, by alluding to French or English history than to a different Italian region.

More positively, a justification for an Italian-wide study of the very diverse peninsula rests on the realisation that at least among the elite of early-modern Italy there were concepts of the unity of ‘Italy’ and Italians. Florentines, Milanese and Venetians might regularly fight each other for control of northern Italy, but they were Italians with a common Roman past dominating an Empire – different from the barbarians, whether Christian French, German, Swiss north of the Alps, or heathen Muslims of the Ottoman Empire threatening across the Mediterranean waters or down from the Slavic north-eastern corner. This attitude of there being different kinds of foreigners, aliens and enemies lies behind the peroration of Niccolo Machiavelli’s notorious The Prince (mainly written 1512–13); Machiavelli wanted the peninsula cleared of non-Italians, especially Swiss and German mercenary soldiers working with Imperial, Spanish or French princes. Despite the interpretations of nineteenth-century nationalists and more recent political scientists, it is difficult to accept that Machiavelli seriously envisaged a single Italian state as a permanent result, but he desired Italy to be free for Italians to contest among themselves. Like his fellow Florentine historian and friend Francesco Guicciardini, he was horrified at the ease of the French invasion of Italy in 1494 that left Italy dominated, if not fully occupied, by non-Italian rulers for the rest of our period. Machiavelli blamed lazy, luxury minded, Italian princes and patricians, and notably the Papacy which had not been strong enough to unite Italy, but strong enough to prevent another ruler from doing so. He wanted an end to Italian decadence, which might virtuously be achieved by a Medici prince from Florence uniting Italian forces against non-Italian barbarians. This reaction to the 1494 invasion generated an increased cultural and moral concept of italianità, but not a political movement for unity.3

Following the Reformation schism and the Catholic reform, church leaders (like Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino) saw Italy as a Catholic church unit; with the Alps and the Inquisition tribunals combining to create a cordon sanitaire to keep out heretics and heterodox ideas. But not till the eighteenth century (and hardly then) was a single Italian state perceived to be feasible or desirable.

The divisions and contrasts within the Italian peninsula were, and are, considerable; between the mainly mountainous areas and the smaller plains, between great cities on coasts and rivers, and numerous città perched on high hilltops; between great feudal monoculture estates growing grain or pasturing sheep, and tiny multipurpose terraced strips mixing vines, olive trees, goats and chickens; between large extended families and the widow-run room of children; between great palace complexes like the Vatican or the Gonzaga palace in Mantua, and the hovels or even caves of the rural poor.

For many historians the fundamental divide in Italy is between the North and the South (the Mezzogiorno). The Mezzogiorno might, for some, include Rome and the surrounding Campagna and the Abruzzi; but more consistently it refers to what was the Kingdom or Viceroyalty of Naples, with the islands of Sicily and Sardinia often included, (although I am largely excluding these islands from my ‘Italy’). The concept of Il Mezzogiorno, or The South, is both geographical and attitudinal. The southern part of Italy has general geographical differences; more adverse climatic conditions, creating less diverse and less rich agricultural conditions; from these derive lower standards of living for most of the population, and more difficult communications. The south is often characterised as maintaining, or re-introducing a more intense ‘feudal’ structure socially and economically, nobles dominating large monoculture estates and having full feudal legal rights over towns and villages. Naples came to dominate the whole region, attracting the elite of feudal property owners, of educated professionals and adventurous international traders. The rest of the South was left with limited capital resources, less diverse occupations, less intellectual challenges; the south lacked the competitiveness of the rival city states and communes of the north. Thence derived the alleged torpor and unproductiveness of the Mezzogiorno. In the eyes of some Italian commentators – exemplified by the philosopher-historian who dominated Italy’s intellectual world from the late nineteenth century, Benedetto Croce, and by a modern Marxist historian, Rosario Villari – the southern problem was exacerbated when Spanish control was consolidated from the early sixteenth century (and ratified in the peace settlement of 1559). Spanish influence supposedly consolidated feudal noble control, emphasising courtly manners, and chivalric codes of behaviour on the part of the elite, with accompanying disdain for hard work, manual labour, and capitalist entrepreneurship. With the addition of rigorous counter-reformation orthodoxy the South lost its renaissance humanism, its intellectual and commercial competitiveness, and lapsed into torpor except when it came to the preservation of ‘honour’ and the pursuit of vendettas.4

Various sections of this book will test these myths or realities. The South has been much less studied than the North, though there have been beneficial changes recently – as with the investigation of socio-religious history, or family and household structures. Hostile impressions have discouraged investigation of the southern past; fewer universities there have meant fewer local researchers. Images of the South, its poverty, its supposed violence and its distrust of outsiders, have discouraged the kind of foreign scholar who has so enriched the study of northern Italy. Within the south, Naples’ past political, economic and cultural predominance seems to have led later historians to ignore Reggio Calabria, Nicastro, Potenza, Cosenza, Taranto, Bari or Lecce for example. These cities apparently rarely made the historical impact that, say, other cities in the Papal State besides Rome did, such as Perugia, Todi, Foligno, Orvieto, Spoleto, Ancona, all of which have attracted international scholarship for studies of our period.

The sources for studying the Mezzogiorno are also much more limited than for the North, because fewer documents and contemporary books were produced in the first place with a less literate, less urbanised, less politically fragmented society. What was produced has suffered from greater attrition, through earthquakes, climatic adversities or German vindictiveness on evacuating Naples in 1944. When and where they do survive, poverty, indifference and ignorance have caused materials in feudal and ecclesiastical archives and libraries to be lost, eaten up, dampened or rendered inaccessible. So the southern problems dictate that attempts to test or change the image are made difficult.

For all the divisions within Italy, ‘Italy’ had an image in the eyes of non-Italians that was largely favourable and/or magnetic, even if the perception of Italy was normally of the nearer and more accessible northern, urban, Italy.5 Through the period of our study, from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries ‘Italy’ (like Europa pursued by Jove), was envied, admired, coveted, lusted, by rulers and the elite of much of Europe. If she did not satisfy or satiate, if gold proved mere gilt, if overtures were rejected, then admirers turned to despisers – as with Erasmus, Luthe...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Map 1: Physical Italy

- Map 2: The Italian States, 1559

- Map 3: Italian cities and towns

- Map 4: The Kingdom of Naples

- Map 5: The city of Venice

- 1: Disunited Italy

- 2: Geography and Demography

- 3: The Changing Rural and Urban Economies

- 4: The Land and Rural Society

- 5: The Urban Environment

- 6: Urban Society

- 7: The Family and Household

- 8: The Social Elites

- 9: Social Groupings and Loyalties

- 10: Parochial Society

- 11: Social Tensions, Control and Amelioration

- 12: Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography