- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Meeting the Standards in Primary Science provides:

- primary science subject knowledge

- the pedagogical knowledge needed to teach science in primary schools

- support activities for work in schools and self-study

information on professional development for primary teachers.

This practical, comprehensive and accessible book should prove invaluable for students on primary initial teacher training courses, PGCE students, lecturers on science education programmes and newly qualified primary teachers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Meeting the Standards in Primary Science by Lynn D. Newton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Welcome to your

Teaching Career

Teaching is without doubt the most important profession; without teaching there would be no other professions. It is also the most rewarding. What role in society can be more crucial than that which shapes children’s lives and prepares them for adulthood?

(TTA, 1998, p. 1)

So, you have decided to become a primary teacher. You will, no doubt, have heard stories about teaching as a profession. Some will have been positive, encouraging, even stimulating. Others will have been negative. Nevertheless, you are still here, on the doorstep of a rewarding and worthwhile career. Without doubt teaching is a demanding and challenging profession. No two days are the same. Children are never the same. The curriculum seldom stays the same for very long. But these are all part of the challenge. Teaching as a career requires dedication, commitment, imagination and no small amount of energy. Despite this, when things go well, when you feel your efforts to help this child or these children learn have been successful, you will feel wonderful. Welcome to teaching.

Recent Development in Primary Teaching

As with most things, the teaching profession is constantly buffeted by the winds of change. In particular, the last decade or so has been a time of great change for all involved in primary education. At the heart has been the Education Reform Act (ERA) of 1988. The Act introduced a number of changes, the most significant of which was probably the creation of a National Curriculum and its related requirements for monitoring and assessment.

Although in the past there have been guidelines on curricula from professional bodies (such as teachers’ unions), local authorities and official government publications, until 1988 teachers generally had freedom to decide for themselves what to teach and how to teach. Different approaches to curriculum planning and delivery proved influential at different times. As far as primary education is concerned, the most influential event before the ERA was probably the publication of the Plowden Report (Central Advisory Council for England, 1967), with its now quite famous phrase, ‘At the heart of the education process lies the child’. Children were viewed as participants in the learning process, not passive recipients of it. Active involvement, a consideration of their needs and interests, the matching of curricula and support to the needs of individuals and groups were all seen as significant developments in the education of primary children. However, by the 1980s, there were those in education and in government who believed that the ‘post-Plowden progressivism’ had gone too far. There was a need to redress the balance, restore a structured curriculum and bring back traditional approaches to the classroom. Blyth suggests that as a consequence over the last decade or so:

The relation between subjects and children’s learning has preoccupied thinking about the primary curriculum especially since Plowden, and has unsurprisingly generated a very substantial body of professional literature.

(Blyth, 1998, p. 11)

This preoccupation not only with the primary curriculum, but with progression in pupils’ learning throughout the period of compulsory schooling and in all subjects, has resulted in the development of the idea of an official curriculum for England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Many other countries already had national curricula, so the idea was not new and there were models to draw upon.

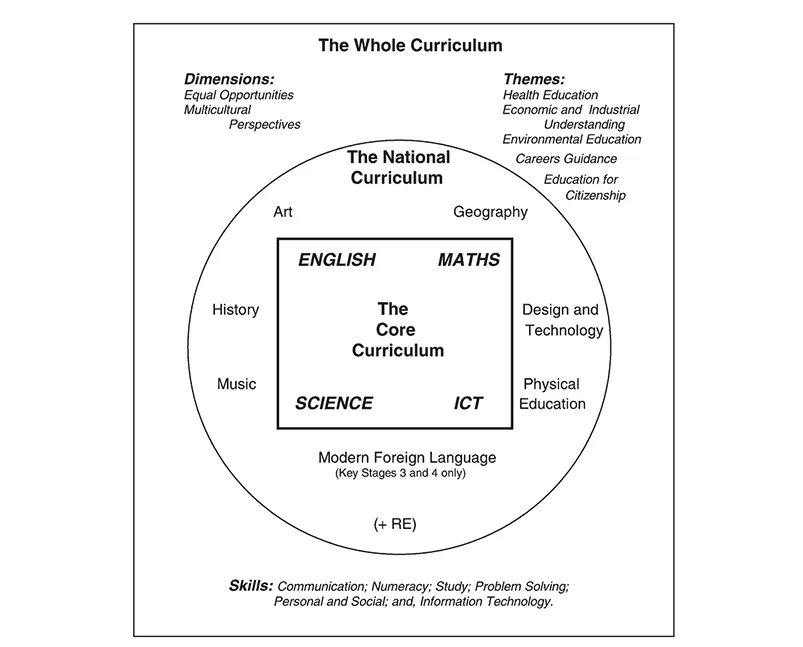

In the second half of the 1980s, the government introduced the idea of a Basic Curriculum for all pupils of compulsory school age. At the heart of this is the National Curriculum, which is underpinned by a subject-led approach to areas of experience and their assessment. The focus of the National Curriculum was a ‘core curriculum’ of English, mathematics and science. This core was supported by a framework of ‘foundation’ subjects: art, design and technology, geography, history, information technology, music and physical education. In Welsh-speaking areas of Wales, Welsh was also included as a core subject and as a foundation subject in other parts of Wales. Outside the National Curriculum, but still embedded within the broader framework of the Basic Curriculum, were areas of experience such as religious education and a range of cross-curricular dimensions, themes and skills which allowed topic and thematic approaches in the primary classroom. This curriculum structure is summarized in Figure 1.1.

Initially grossly overloaded, the National Curriculum underwent a sequence of judicious prunings. The most drastic was in 1995, when Sir Ron Dearing reduced and reorganized the content, placed more emphasis on the key skills which all pupils should acquire and allowed the cross-curricular dimensions, themes and skills to disappear into the background. This generated a slimmed-down document which addressed some of the criticisms and concerns of primary teachers, and was accompanied by a promise that teachers would have a five-year period of calm. Revisions of the current National Curriculum are underway and will see Information and Communications Technology (ICT) introduced as the fourth core area.

Figure 1.1 A representation of the primary school curriculum (At the heart of the basic curriculum is a core of English, mathematics, science and ICT, supported by the foundation subjects, such as art and history, plus religious education. The National Curriculum is embedded in the broader framework of the Whole Curriculum, which incorporates a range of cross-curricular dimensions, themes and skills.)

The Standards Debate

Parallel to the changing perspectives on curriculum has been an increasing emphasis on standards. There has, in essence, been a shift in perspective from equality in education (as reflected in the post-war legislation of the late 1940s) to the quality of education.

The term standard is emotive and value-laden. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, it is: ‘(i) a weight or measure to which others conform or by which the accuracy of others is judged; and (ii) a degree of excellence required for a particular purpose’. Both definitions sit well with the educational use of the term, where it translates as acceptable levels of performance by schools and teachers in the eyes of public and politicians alike.

Over the last decade, the media have reported numerous apparent instances of falling standards. This, in part, was a major force behind the introduction of the National Curriculum and its related assessment procedures. In 1989, when the National Curriculum was first introduced, it was claimed that:

There is every reason for optimism that in providing a sound, sufficiently detailed framework over the next decade, the National Curriculum will give children and teachers much needed help in achieving higher standards.

(DES, 1989, p. 2)

Underpinning these forces of change in primary education have been two major emphases. The first is to do with the curriculum itself and the experiences we offer pupils in primary schools. The second, and not unrelated, is to do with how we measure and judge the outcomes of the teaching and learning enterprise. To achieve the appropriately educated citizens of the future, schools of the present must not only achieve universal literacy and numeracy but must be measurably and accountably seen to be doing so, hence the introduction of league tables as performance indicators.

David Blunkett, the Secretary of State for Education and Employment, said in 1997:

Poor standards of literacy and numeracy are unacceptable. If our growing economic success is to be maintained we must get the basics right for everyone. Countries will only keep investing here at record levels if they see that the workforce is up to the job.

(DfEE, 1997, p. 2)

While the economic arguments are strong, we need to balance the needs of the economy with the needs of the child. Few teachers are likely to disagree with the need to get the ‘basics’ right. After all, literacy and numeracy skills underpin much that we do with children in science and in other areas of the curriculum. However, the increased focus on the ‘basics’ should not be at the expense of these other areas of experience. Children need access to a broad and balanced curriculum if they are to develop as broad, balanced individuals.

All primary schools are now ranked each year on the basis of their Key Stage 2 pupils’ performances in the standardized tests (Standard Assessment Tasks (SATs)) for English, mathematics and science. The performances of individual children are conveyed only to their parents, although the school’s collective results are discussed with school governors and also given to the local education authority (LEA). The latter then informs the Department of Education and Employment (DfEE), who publish the national figures on a school/LEA basis. This gives parents the opportunity to compare, judge and choose schools in their area. The figures indicate, for each school within the LEA, the percentage above and below the expected level, that is, the schools which are or are not meeting the standard. This, inevitably, results in debate about whether standards are rising or falling. Such crude measures as SATs for comparing attainment have been widely criticized. Fitz-Gibbon (1995) emphasized that such measures ignore the ‘value added elements’, the factors which influence teaching and learning such as the catchment area of the school, the proportion of pupils for whom English is an additional language, and the quality and quantity of educational enrichment a child receives in the home. Davies (1998) suggests that,

Dissatisfaction [with standards] is expressed spasmodically throughout the year but reaches fever pitch when the annual national test results are published. Whatever the results, they are rarely deemed satisfactory and targets are set which expect future cohorts of children to achieve even higher standards than their predecessors.

(Davies, 1998, p. 162)

Targets to be achieved by schools by the year 2002 include, for example, those to do with raising the standard of literacy and numeracy and improving standards of class management and control.

There are also targets for initial teacher training, to redress the perceived inadequacies in existing course provision. These centre on a National Curriculum for initial teacher training, prescribing the skills, knowledge and understanding which all trainees must achieve before they can be awarded Qualified Teacher Status (QTS). As a trainee for the teaching profession you must be equipped to deal with these demanding situations as well as meeting all the required standards. How will you be prepared for this?

Routes into a Career in Teaching

Let us first consider the routes into teaching open to anyone wanting to become a teacher. Teaching is now an all-graduate profession, although this has not always been the case. For most primary teachers in the United Kingdom, this has usually been via an undergraduate pathway, reading for a degree at a university (or a college affiliated to a university) which resulted in the award of Bachelor of Education (BEd) with Qualified Teacher Status (QTS). Such a route has usually taken at least three and sometimes four years. More recently, such degrees have become more linked to subject specialisms and some universities offer Bachelor of Arts in Education (BA(Ed)) with QTS and Bachelor of Science in Education (BSc(Ed)) with QTS. A smaller proportion of primary teachers choose to gain a degree from a university first, and then train to teach through the postgraduate route. This usually takes one year, at the end of which the successful trainee is awarded a Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) with QTS. In all cases, the degree or postgraduate certificate is awarded by the training institution but QTS is awarded by the DfEE as a consequence of successful completion of the course and on the recommendation of the training institution. Whichever route is followed, there are rigorous government requirements which must be met by both the institutions providing the training and the trainees following the training programme before QTS can be awarded.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, a number of government initiatives have moved initial teacher training in the direction of partnership with schools. This has meant school staff take greater responsibility for supporting and assessing students on placements. A transfer of funds (either as money or as in-service provision) is made to the schools by the universities in payment for this increased responsibility. Alongside this, school staff have increasingly become involved in the selection and interviewing of prospective students, the planning and delivery of the courses and the overall quality assurance process.

More recent legislation established the Teacher Training Agency (TTA), a government body which, as its name suggests, has control over the nature and funding of initial teacher training courses. This legislation is important to you as a trainee teacher, since the associated documentation defines your preparation for and induction into the teaching profession. How will the legislation affect you?

TTA Requirements on Courses of Initial

Teacher Training

In 1997, a government circular number 10/97 introduced the idea of a national curriculum for initial teacher training (ITT), to parallel that already being used in schools. This major focus in the training of teachers is on the development of your all-round professionalism. It implied:

more than meeting a series of discrete standards. It is necessary to consider the standards as a whole to appreciate the creativity, commitment, energy and enthusiasm which teaching demands, and the intellectual and managerial skills required of the effective professional.

(DfEE, 1997, p. 2)

At the heart of this is the aim of raising standards. Circular 10/97 had specified:

- the standards which all trainees must meet for the award of QTS;

- the initial teacher training curricula for English and mathematics; and,

- the requirements on teacher training institutions providing courses of initial teacher training.

Subsumed under (1) were groups of standards relating to the personal subject knowledge of the trainee, criteria ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Meeting the Standards Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Series Editor's Preface

- 1 Welcome to Your Teaching Career

- Part 1 Your Science Skills and Knowledge Base

- Part 2 Your Science Teaching and Learning Base

- Part 3 Your Continuing Professional Development

- Part 4 Further Information

- References

- Index