![]()

PART I

Introducing the

Dimensions of Literacy

and Their Instruction

The first two chapters of this book set forth an overview of the dimensions of literacy as well as provide an in-depth look at how the dimensions are developed. The chapters reflect the belief that effective literacy instruction involves more than passively following and implementing a series of recipes. Rather, teaching is a conscious, reflective, and constructive process whereby teachers enact instruction based on their knowledge of their discipline, in this case the reading and writing processes, and knowledge of their children. In an age of standardized curricula and standardized tests, more than ever we are in need of teachers who are capable of taking on the responsibility for promoting the literacy learning and development of their children. This is only possible if practitioners have a deep understanding of how the literacy processes are actually learned and developed. The following two chapters are intended to provide such an understanding.

![]()

| one |

| Introducing

the Dimensions

of Literacy |

The ongoing debate and controversy concerning how best to teach our children to read and write shows no signs of dissipating (e.g., Coles, 2000; Cunningham, 2001; Ehri, Nunes, Willows, Yaghoub-Zadeh, & Shanahan, 2001; Gee, 2004; Hornsby & Wilson, 2010; Kucer, 2009a; Luke, 1998; Schmidt, 2008). These disputes, which are played out in both academic and public arenas, might lead a casual observer to the conclusion that little is actually known about literacy and its instruction. Despite these debates, or perhaps because of them, our understanding of literacy has increased dramatically over the last several decades. In fact, it might be argued that it is just this explosion in knowledge that has contributed, at least in part, to the disputes. Unfortunately, scholars with an interest in literacy oftentimes focus on or privilege one dimension or part of literacy learning to the exclusion of the others. The result may be classroom literacy instruction that narrows or constricts both the teacher’s and the children’s understanding of literacy teaching and learning. However, as Ed Young reminded us in The seven blind mice (1992), “knowing in part may make a fine tale, but wisdom comes from seeing the whole” (n.p.).

Compounding the problems associated with the limited scope of this “fine tale”—literacy instruction—is the fact that the tale changes over time. “What’s hot and what’s not” in education or what is in and out of fashion has been the butt of jokes as well as scholarship. Reading Today, a publication of the International Reading Association, for example, publishes a yearly report that identifies literacy issues that are “in” and “out” for the year (e.g., Cassidy & Cassidy, 2010). To a certain extent, such critiques of changes in education as representing mere fads are probably overstated. In fact, some scholars have even argued that, historically, educational research has had minimal impact on the classroom (Hiebert, Gallimore, & Stigler, 2002). The nature of instruction has remained relatively stable over the last century (Cuban, 1990), with perhaps an ever-increasing segmentation of instruction being the one exception. When literacy is narrowly conceived, oftentimes what appear to be advances in instruction represent little more than a shift in focus rather than an expanded understanding of literacy development. Unlike other scientific discoveries, these shifts in instructional foci may not significantly improve the lives of teachers and students.

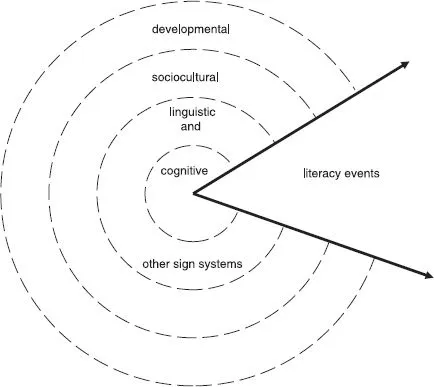

If literacy teaching and learning are to be effective, it is important that we move from a fine tale to wisdom—to seeing the whole. It has been well established that literacy is dynamic and multidimensional in nature (e.g., Bernhardt, 2000; Gee, 1996; Kucer, 2009a; Luke 1995, 1998; New London Group, 1996). Becoming literate—a never-ending process—reflects learning to manage or juggle these various aspects. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, every act of real-world use of written language involves four dimensions: linguistic, cognitive, sociocultural, and developmental. At the center of the literacy act is the cognitive dimension, the language user’s exploration, discovery, construction, and sharing of meaning. Even in those circumstances where there is no intended “outside” audience, such as in the writing of a diary or the reading of a novel for pure enjoyment, there is an “inside” audience, the language user himself or herself. Regardless of the audience, the generation of meanings always involves the employment of various mental processes and strategies, such as predicting, revising, and monitoring. Interestingly, this cognitive dimension seems to transcend languages. Readers may employ many shared mental processes and strategies whether reading in their first or second language (Chamot & El-Dinary, 1999; Dressler & Kamil, 2006; Genesee, Geva, Dressler, & Kamil, 2006; Goldenberg, 2011). In the cognitive dimension, the individual is acting as a meaning maker.

Surrounding the cognitive dimension is the linguistic and other sign systems dimension. This dimension involves the various vehicles or avenues through which meanings are constructed and shared. Literacy depends on such linguistic systems as graphophonemics, syntax, and semantics, and proficient language users have a well-developed understanding of how these systems operate. Not limited to language alone, readers and writers also make use of other sign systems for meaning making, such as color, sound, illustration, movement, etc. More than ever, literacy is a multimodal act. Although the understandings of how this dimension operates may be implicit—the rules for language and other sign systems cannot be consciously verbalized—the understandings are explicitly demonstrated every time the individual engages in a literacy event. When readers or writers put eyes or pen to paper—or eyes or fingers to keyboards and screens—they must coordinate these transacting language and sign systems with the meanings being constructed. Here, the individual is a code breaker and code maker.

FIGURE 1.1. Dimensions of Literacy.

Literacy events, however, are more than individual acts of meaning making and language and sign system use. Literacy is a social act as well. When individuals read or write, they bring not only their own personal experiences but also the experiences of the various social groups in which they hold membership. Our gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, for example, all impact how we understand, interpret, and critique any article we might read in the New York Times. We never read or write alone; our social identities are always sitting on our shoulders. Acting as text user and text critic is the role of the individual within the sociocultural dimension.

Finally, encompassing the cognitive, linguistic, and sociocultural dimensions is the developmental dimension. Each literacy event reflects those aspects of literacy that the individual does and does not control in any given context. Potentially, development never ends. Rather, development continues to unfold as the individual encounters communicative situations that involve using the literacy dimensions in new and novel ways. These experiences offer the opportunity for the individual to build new understandings and learnings that result in developmental advancements. As we discuss in the next chapter, the individual develops this knowledge much as a scientist and construction worker would.

Although defined separately, reading or writing requires the individual to utilize knowledge of the four dimensions of literacy in a transactive, symbiotic manner. Each dimension informs and is informed by the others. The challenge faced by the individual is to juggle and integrate both the constraints and possibilities offered by each dimension. Rarely in the national debates over literacy instruction, however, are reading and writing addressed in such a multidimensional, textured, and complex manner. If literacy use inside school is to reflect as well as promote literacy use outside school, it is imperative that teaching and learning adequately reflect the dimensional nature of the reading and writing processes. Instructional wisdom calls us to help our students develop literacy in all of its richness and complexities.

Highlighting Versus Isolating the Teaching and Learning of the Dimensions of Literacy

Identifying and defining the dimensions of literacy is a relatively easy task. There is a plethora of research that can guide us in this endeavor. The real challenge is in the development of curricular and instructional strategies that promote the teaching and learning of the dimensions. Historically, instruction in general, and literacy instruction in particular, has tended to take complex processes, divide them into bits and pieces, and present them in a scoped and sequenced manner. Instruction of this type is so pervasive as to have become a cultural norm of schooling. Alternatives are oftentimes deemed to be deviant and may even receive social sanctions (Compton-Lily, 2005; Wolfe & Poynor, 2001).

The problem with this type of instruction is twofold. First, when literacy is taken apart, the individual pieces may operate differently than when they are part of the whole. It is well established, for example, that teaching children to spell in isolation from the writing process is largely ineffectual (Wilde, 1992, 1997). The children may, in fact, learn the words for the test on Friday, and then will turn around and misspell the same words in their stories on Monday. Or, that teaching phonics in isolation does not significantly impact comprehension for monolingual learners (Institute of Education Sciences, 2008) or bilingual learners (Sen & Blatchford, 2001). Children may be taught to sound out the individual letters in words on flash cards and then discover that this kind of fine-grain analysis is not required when reading the words within the context of a story.

Second, proficiency requires the ability to juggle all of the dimensions as the literacy event unfolds. Readers and writers are called to consider and use their knowledge of the dimensions simultaneously. When literacy is learned piecemeal, many learners are confronted with the difficulty of putting the pieces back together. As John Dewey (1938) reminded us many decades ago, the manner in which something is learned impacts the manner in which it can be used. We have far too many students who have mastered the pieces yet still struggle to use reading and writing outside of the school walls. The last thing needed is for us to take the four dimensions of literacy, divide each into a set of skills, and then to teach these skills in isolation and in sequence. We have been down that path far too often.

The problems related to breaking instruction into small parts become even more complex when working with English language learners (ELLs) in English as a second language (ESL) or bilingual settings. Common sense might dictate that in order to make literacy development easier for second language learners it is a good idea to begin reading instruction by teaching the small parts—for example, letter names and sounds. In reducing the complexity of this instructional task, however, one also reduces the levels of support available to a reader in order to make predictions and construct meaning. Left with the task of recognizing a simple letter, the reading act becomes a meaningless task.

Rather than isolating the dimensions, we believe that a more effective response is to highlight them. In such instructional contexts, students are engaged in real-world, meaningful, and authentic literacy activities. All dimensions are available and operating together. Special attention or emphasis, however, is given to a particular aspect of literacy within the whole. Repeated reading, a strategy in which students read a particular text a number of times, is a good example of such highlighting. In the first reading, students are encouraged to respond to the meanings bei...