- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily

About this book

First Published in 2004. This work throws fresh light on the island's past and seeks to provide a concise, up-to-date guide to Sicilian archaeology, covering the period from prehistory to Constantine the Great. It should be of interest to students and lecturers in European archaeology and ancient history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily by R. Ross Holloway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 PREHISTORIC SICILY

The Palaeolithic

Up to thirty years ago there was no evidence that man came to Sicily until the last great advance of the polar icecap and the Alpine glaciers in Europe was more than half over. This was approximately 30,000 years ago. The oldest known Sicilian flint tools from the rock shelter of Fontana Nuova (Marina di Ragusa) consisted of the sturdy blades, gravers, burins (pointed gravers) and scrapers that also characterize the opening phase of the Upper Palaeolithic in France (where the typological sequence used throughout Europe was developed).

During the excavation of the classical site of Heraclea Minoa at the mouth of the Platani River on the southern coast in the 1960s numerous flakes from prehistoric flintworking were found to have been employed as temper in the sundried brick of the city’s fortifications. And just outside the walls flint tools were collected on the surface. Like the flakes which had found their way into the mud bricks, the tools belonged to a Lower Palaeolithic industry, and among them there was an amygdaloid hand ax, an object fashioned from a flint core, in shape like a pear with an extended neck, in size and weight approximating the head of a small sledge hammer. With this discovery (which has been extended by further finds ofhand axes in various locations), the prehistory of Sicily leapt back half a million years.

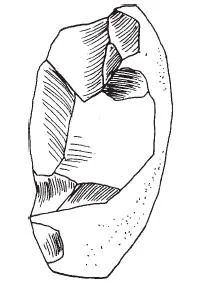

At the same time Gerlando Bianchini, a bank manager from Agrigento, was patiently combing the countryside for traces of early man. His persistence and dedication were crowned by a series of discoveries which eclipsed even the Heraclea hand ax. At various sites Bianchini found the earliest form of tool lying on the surface of the ground. They are called ‘chopping-tools’ and consist of smoothed rocks from ancient beaches, large enough to fit the palm conveniently and intentionally chipped along one side (figure 1). The material is limestone or quartzite, as well as flint. The flaking is rudimentary, although it may either be in one direction or result from two operations carried out in opposing directions. ‘Chopping-tools’ antedate modern man, his Middle Palaeolithic cousin the Neanderthal, and their predecessor, Homo Erectus, who used amygdaloid hand axes. The ‘chopping-tools’ belong to an earlier era, extending back at least 2 million years, when beside the members of that slender lineage which led to modern man there were tool-using hominids known generically as Australopithecans.

Figure 1 Chopping-tool

Although reports of the discovery of hominid physical remains in Sicily remain unconfirmed, Bianchini’s work made it clear that, together with Africa, Asia and Europe, Sicily had witnessed the whole history ofhominid and human industry. But there was a serious problem involved in this discovery: how had the hominids reached the island? Coming from Africa, where the remains of the earliest hominids have been found, any creature, it would seem, faced the barrier of the deep trench in the ocean floor between Sicily and Tunisia which ensured that Sicily remained separated from Africa even during periods of glacial advance when the sea level dropped sharply. The depth of the Straits of Messina, however, would not have prevented the formation of a land bridge at various times during the glacial age.1

Following the hominid tool-makers of the Lower Palaeolithic but coming before modern humans were the Neanderthals, a strain of man that was not destined to survive. The stone tools of the Neanderthals belong to what is called the Mousterian, a complex set of industries found over Europe, Africa and the Near East. The tool kits of Mousterian type are produced not from cores but from flakes, such as had already been employed in certain industries of the Lower Palaeolithic. The flaking technique, however, especially the retouching along the edges, is smaller and more closely spaced, creating an impression of precision and often of symmetry. It is doubtful whether there is a true Mousterian in Sicily; those few materials which might be associated with it may in fact belong to industries of the developing phases of the Lower Palaeolithic. No physical remains of Neanderthal type have yet been discovered on the island.

The appearance of modern man in Sicily (some time after 30,000 BC) is shown by the flint tools from Fontana Nuova (Marina di Ragusa) mentioned earlier. Otherwise, the initial phases of the Upper Palaeolithic are hardly documented in the island, and it is only in the latest stages of the Upper Palaeolithic, about 10,000 BC, that sites multiply. This is the time of the end of the last glaciation and the establishment of the landforms we know today. The Upper Palaeolithic inhabitants sought out shelter beneath rock outcroppings, and although they left their traces throughout the island, these are especially frequent on the north coast around Palermo. In this area the cliffs that dominate the coast were, in distant geological time, submerged in the sea. As a result they were eroded in vertical channels which often widen at the base to create hospitable shelter and from which large caves penetrate the mass of the formations.

The flint industry of these stations is termed Epigravettian, after the equivalent stage of the French sequence. It is based on small carefully shaped flakes worked into blades and bladelets, burins, other gravers and scrapers, all finished with minute retouch flaking on the edges. There are also small triangular or crescent-shaped microliths, perhaps arrow-tips. The miniaturization of the flint tools at the end of the Palaeolithic, generally for insertion in bone or wood handles or shafts, is a universal phenomenon. Hunting was man’s livelihood, as it had been for eons past. The large animals of the Pleistocene (the Age of the Glaciers), the elephant, which existed in a dwarf variety during most of the period in Sicily, the hippopotamus, the hyena, all had departed. Their only surviving representative was Equus Hydruntinus, an ancestor of the donkey. But the Epigravettian hunters took wild boar, deer, fox, wild cattle and wild goat. As the period progressed the inhabitants of coastal sites show an increasing taste for shellfish.

For the first time, in the Epigravettian, archaeology brings us in contact with the intellectual world of early man in Sicily. The cave at Cala dei Genovesi on the island of Levanzo, close to the western extremity of Sicily, and joined to Sicily during the Late Palaeolithic, is the key to Sicilian Palaeolithic art. The Epigravettian deposit from the interior of the cave contained a detached slab of rock on which the figure of a bovine creature had been incised. This discovery serves to confirm the Palaeolithic date of other depictions on the walls of the same cave, together with rock engravings at other sites, especially those discovered in the caves of Monte Pellegrino overlooking Palermo. The same stratum in the Cave on Levanzo has also given a radiocarbon date just before 9,000 BC.

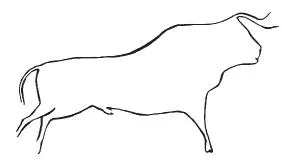

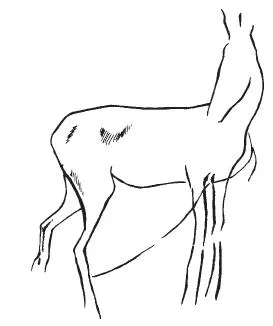

The style and the subject of the Levanzo bovine belong to the great tradition of Palaeolithic art in Western Europe. The firm outline of the creature and its attenuated horns are not too distant from the famous painted bovines of Lascaux; the other representations of bulls, cows, deer and horse on the walls of the Levanzo cave have even greater similarities to the animals of the mature phase of Franco-Cantabrian cave painting and engraving (figure 2). The drawing is assured and elegant. The bull is seen in all his massiveness and grandeur. The small wild horses lowering their heads to graze have all the nervous hesitation of their subjects in life, as does the movement of the stag in the same gallery. One wild goat is drawn in foreshortening, the body in profile but the head turned toward the viewer (figure 3).

The significance of these subjects and the reason for their depiction in the recesses of caves is still far from clear. Few would doubt that they are governed by the same impulses that drew men to venture into the unlit depths of the earth. Was the object of man’s adventures in the cave revelation of wisdom from secret sources or spectral ancestors? Was it the imparting of knowledge to cowering initiates? Was it preparation for the great endeavors of life, foremost among which must have been the hunt? Our answers to these questions can rely only on our ingenuity or ethnographic analogies to modern hunters and gatherers, whose intellectual attainments, complex and surprising as they may be, are probably a poor guide to the powers of the Palaeolithic mind. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, because of the work of André Leroi-Gourhan,2 we can appreciate, in the French and Spanish caves, the logic of the placement of groups of images and thus their relation to a systematic pattern of thought. The Sicilian representations show that the inhabitants of the island participated in the same tradition.

Figure 2 Levanzo, rock engraving

Figure 3 Levanzo, rock engraving

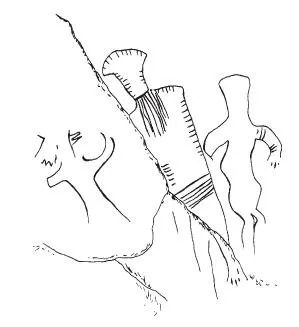

Because they are late in the history of Palaeolithic art, the Sicilian engravings show a development toward scenes of human activity such as occur in the post-Palaeolithic art of Spain and Africa but are seen only fleetingly in earlier representations. The cave of the Cala dei Genovesi gives us a detailed sketch of a human figure in what must be ceremonial costume (figure 4). The figure wears a wide belt and above it a shirt or jacket which has decorative stitching or a fringe on its shoulders and sides. The figure clearly wears a hat, but although from the head alone one cannot be sure whether the figure is seen from the front or the rear, the fact that the toes of the left foot are shown makes it certain that this is a frontal view. The cap, peaked like a chef’s hat, with stitching or a fringe shown as on the jacket, covers the whole face and apparently has no openings for the mouth, eyes or nose. Rather than a patriarchal beard, I would surmise that the engraving shows a long fringe attached to the headgear or possibly to the bottom of a beaded veil. Considering that the headdress effectively imprisons the wearer, the absence of arms from the shirt may indicate that it was a kind of straitjacket.

Figure 4 Levanzo, rock engraving

The individual thus restrained is flanked by two other figures. At the right there is an individual with bracelets on his arms, but no other detail of clothing, unless the peculiar form of his head is meant to suggest a hat like that of the central personage. At the left there is the partially executed sketch of another human, often said to be wearing a bird headdress because of his bill-like mouth. If we take the figures together, the two small ones seem to be dancing around the masked and hobbled individual in the center. Such a sense of deprivation and physical restraint in a setting of mystical mimicry would not be out of place in initiation ceremonies or in the mysteries of the shaman. A further possibility may be the rites of hunting magic with the central figure playing the role of the magically handicapped animal.

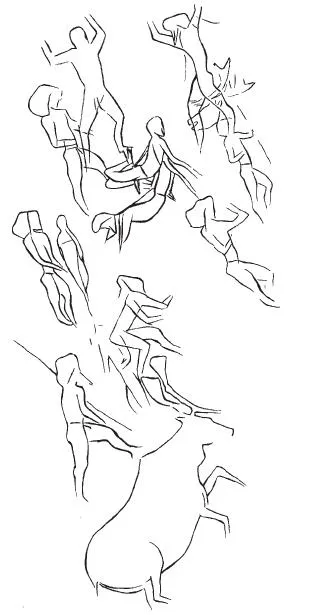

Figure 5 Monte Pellegrino, rock engraving

A similar scene, but with a larger group of actors, was found in 1952 in the small cave of Addaura on Monte Pellegrino, the sugarloaf eminence that rises from the sea and overlooks Palermo from the west. The rock face, on which the scenes were incised, receives illumination from the mouth of the cave. The ritual scene is part of a larger group of representations of bo vines, deer, equines and humans (figure 5). It consists of eight large figures, presumably male, five of whom are dancing in an animated fashion (one stooping, two with arms raised) while another approaches and the last stands by accompanied by a small figure, very likely a woman, whose size, cylindrical body and long lock of hair by her left side all contrast with the appearance of the men. The men seem to be naked save for a sack-like headdress. In one case this has a bill-like piece on its face not unlike the bill of the figure from the Levanzo cave. In the center of the circle there are two figures, both men. Both seem to be lying on the ground. They are restrained by cords which run down their backs from their necks to their legs. In the case of the upper figure the cord seems to reach the ankles. The result is that the figure’s lower legs are bent backwards, preventing him from rising from the ground. The second figure, partially covered by the first, is evidently in a similar situation. Both have headdresses like the dancers, but it is impossible to say whether these are completely closed like the headdress of the Levanzo figure. The arms of the second figure are stumpy and may be held in some kind of jacket without openings for the hands.

The scene is thus very similar to the Levanzo engraving. It has been suggested that it shows an acrobatic performance, possibly connected with initiation ceremonies, or that the two figures on the ground are actually about to be strangled by the cords around their necks. But the representation of a hunting ritual in which two of the dancers play the part of captured and trussed-up animals is, I feel, more likely.

Animal representations in the grand tradition have been found in other caves on Monte Pellegrino and elsewhere in Sicily. Small smooth stones decorated with simple lines in rows were discovered on Levanzo, and they find parallels on the Italian mainland at the cave site of Praia a Mare on the southwestern coast of the peninsula. Otherwise, small scale carving or engraving (French art mobilier) is surprisingly rare in Palaeolithic Sicily. Recently, however, Giuseppe Navarra has published an extensive collection of figurines in compact sandstone, executed, according to his analysis, by pecking with stone punches3. He attributes these pieces to the early Upper Palaeolithic. The subjects represented are humans, male and female, as well as heads, isolated eyes and the elephant (figures 6 and 7). Although the need for sculpting the stone may have been much reduced by t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- 1. Prehistoric Sicily

- 2. Early Greek Sicily

- 3. Late Archaic and Classical Greek Sicily

- 4. Coinage

- 5. Later Greek, Punic and Roman Sicily

- 6. The Villa At Piazza Armerina

- Notes

- Bibliography (1980–9)