- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Guidelines for Baseline Ecological Assessment

About this book

These best practice guidelines present the type and level of detail required for describing and evaluating the ecological baseline of an environmental assessment. These assessments are vital in determining whether or not there are issues of ecological importance for a site or proposed development and are an essential component of the environmental impact assessment process.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

PART ONE

Introduction

Aims of the guidelines

1.1 This guidance note has been prepared as one of a series of documents published by the Institute of Environmental Assessment (IEA) to establish good practice for car rying out var ious aspects of Environmental Assessment (EA) in the UK. Environmental Assessment is an environmental management tool which has been in use on an international basis since 1970. It is a process by which the identification, prediction and evaluation of the key impacts of a development are undertaken and the information gathered is used to improve the design of the project and to inform the decision making process. The process is illustrated in Appendix 1. EA was formally introduced in the UK through the EC Directive of 1985 (CEC, 1985) and was implemented in 1988 through a series of statutory instruments known as the EA regulations.

1.2 These guidelines concentrate on outlining best practice for describing and evaluating the ecological baseline of an EA. The guidelines should not be regarded as exhaustive or as providing definitive advice but merely as general guidance on the extent to which ecological information should be presented in various situations.

1.3 The guidelines are needed:

- to guide ecologists in their work and to promote best practice.

- to inform project managers and clients about the role of ecology in EA and help them to set appropriate briefs and budgets.

- to guide the determining authorities in assessing ecological statements accompanying EAs.

Scope of the guidelines

1.4 These guidelines, have been prepared by an Institute of Environmental Assessment Working Group (see Preface) and have been subject to an extensive public consultation phase. They represent a consensus on the level of baseline data required to assess adequately the ecological impacts of proposed developments. After the Introduction, Part Two explains the importance of consultation and scoping, and outlines some of the general issues that should be considered when planning and undertaking more detailed ecological studies. Part Three presents the specific criteria which would indicate the need to present more detailed data on various ecological groups, together with recommended survey methods and guidance on evaluating the collated baseline data.

1.5 Unfortunately, due to constraints on time and information, it has not been possible to include specific criteria and survey methods for fungi. However, fungi play an important role in the ecosystem and it may need to be considered in an ecological assessment.Therefore it is intended to include a section on fungi in a future edition of the guidelines. Finally, Part Four covers the requirements for more detailed surveys in marine and estuarine systems.

1.6 The ecological impacts of proposed developments may involve habitat loss or modification and a potentially wide range of other impacts which will vary from project to project and according to location. Due to the wide variation of both habitats and of the proposed developments which may affect them, these guidelines are designed to be flexible. Much effort has gone into ensuring that the methods outlined are the best available for studying particular species and groups. However, each assessment will be unique and the method chosen to characterise baseline ecological conditions is likely to be tailored to the site and the impacts expected. Therefore, it is for the ecologist(s) conducting baseline surveys to make their own professional assessment in the choice of methods to be used. These guidelines should be seen as an aid to practitioners in deciding the level of detail required to characterise baseline conditions adequately.

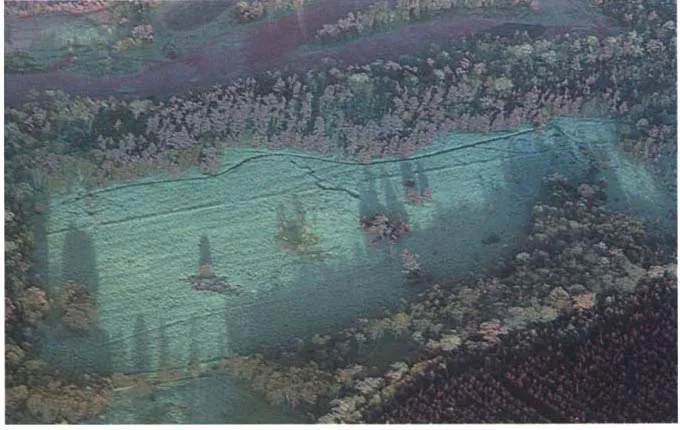

False colour photography can be used to identify stressed vegetation. The dark band at the top is a well watered golf course, the pale area in the middle is a heathland nature reserve and the line of white oaks towards the bottom of the picture are under water stress. The recent conifer planting has greatly affected the water regime in the vicinity

1.7 The first steps in an ecological assessment are to visit the proposed development site and its surrounds, collect any existing ecological data on the area to be affected and consult with various statutory and voluntary conservation agencies.

1.8 However, it is normally the case that insufficient data exist upon which a judgement about ecological impact can be based. Therefore, the main problem facing the ecologist is how much data will need to be gathered to supplement pre-existing information and to assess whether a significant impact on a particular taxonomic group or ecosystem will occur.

1.9 The issues covered by these guidelines are, of course, only part of the Environmental Assessment process. The guidelines do not address how to assess and evaluate the ecological impacts of alternative proposals, how to assess changes in the baseline conditions that would occur in the absence of the project proceeding, how to predict and quantify ecological impacts, how to mitigate these impacts, how to assess the significance of residual (after mitigation) changes brought about by the development or to suggest ecological monitoring requirements. Guidance on some of these issues has been or is about to be published (Forbes and Heath, 1990; Walsh et al. 1991; Box and Forbes, 1992; Department of Trade, 1993; English Nature, in prep. Department of the Environment, in prep.) and will also be addressed by future IEA working groups.

1.10 Whilst these guidelines have been prepared as advice on reasonable best practice for part of the Environmental Assessment process, the same principles may be used for determining the level of information required for other ecological reports (eg environmental appraisal reports accompanying planning applications, ecological elements of CIMAH assessments, IPC applications, BS7750 and EcoManagement and Audit Regulation Environmental Effects Registers, and licences and consents under the Water Resources Act 1991).

Summary

- The guidelines have been prepared by an IEA working group and published after extensive consultation with the various interested parties in the Environmental Assessment process.

- The guidelines represent a consensus viewpoint as to the level of baseline data that is required to adequately assess the ecological impacts of proposed developments. Different aspects of the Environmental Assessment process are covered by other publications, and will also be addressed by future IEA guidelines on these aspects.

- The ecological criteria set out in the guidelines could also be used to help in defining the level of information sufficient to characterise ecological conditions for other types of ecological appraisals.

PART TWO

Principles and good practice of ecological assessment

Defining the Scope of an Ecological Study

Introduction

2.1 Correctly defining the scope of an EA prior to starting the assessment process is essential to the production of a good quality Environmental Statement. Scoping is responsible for focusing on a subset of key issues and potential impacts, some of which will be ecological impacts.

2.2 For many types of impact (eg noise and visual impacts) an initial visit to the site, consultation with interested parties and a full description of the proposed development enables the scope of the study for these issues to be determined. With ecological impacts, however, some initial work (eg data collection, habitat assessment) in addition to the above stages often needs to be done in order to identify the important issues on which to focus the study. Determining the scope of the ecological aspects of the EA is thus more of an iterative process—a certain level of work needs to be done in order to determine:

- whether or not there are issues of ecological importance for the site.

- where significant impacts are predicted, whether there are suffcient data available on the various ecological communities which may be affected to assess the magnitude and significance of those impacts or whether as part of the assessment process additional survey information will be required.

2.3 This section defines the work necessary to determine the above points and thereby scope the ecological elements of the EA. This process is illustrated in Figure 1 (see pg.). It therefore represents the level of ecological study which should be undertaken for all EAs and comprises the following elements:

- consultation and the gathering of relevant existing ecological data for the affected site and its surrounds.

- a site visit and preparation of a relevant type of Phase 1 habitat map identifying any areas of importance for floral or faunal communities.

2.4 All ecological field surveys must be carried out by appropriately qualified ecologists, with relevant field experience of the survey methods being used and of the species or habitats under study. In view of the broad range of specialisms inherent in ecology, it is of paramount importance that individuals only undertake survey work that is within their area of competence.

2.5 The professional competence of ecologists to be engaged on a project may be gauged by their attainment of a combination of credentials including, one or more of the following:

- relevant academic qualifications;

- proven track record in ecological field surveys and/or specialist taxonomic fields;

- membership of an appropriate professional body;

- fulfilment of continuing professional development requirements;

- internal training programmes and informal examination schemes; and

- supplementary qualifications, for example, identification qualifications.

2.6 Details of entry requirements, code of ethics and continuing professional development requirements can be obtained from the professional institutes listed in Appendix 6.

Consultation and Data Collection

2.7 Appendix 2 lists the statutory consultees who should be contacted at the beginning of the scoping process to help define the likely significant ecological impacts of the proposed development and also to identify existing data which could assist in defining the baseline ecological conditions.

2.8 Appendix 2 also lists some of the other organisations which may hold relevant ecological data and may be able to assist in defining the scope of the ecological study. Donn and Wade (1994) have published a comprehensive county by county list of ecological information sources and their contact addresses. In addition to these sources, previous experience has shown that local naturalists can frequently provide some of the most extensive and reliable data. However, it should be appreciated that the time and resources of many local specialists and many of the organisations listed by Donn and Wade (1994) are often severely limited and may easily be overwhelmed by constant requests for information and advice. Access to certain information, such as the location of rare and protected species, may also be restricted and charges for information should be expected.

2.9 The desk study should also encompass published sources of information such as the Ancient Woodland Inventory (Spencer and Kirby, 1992) and county and national atlases of flora and fauna (eg Harding, 1993) and the Invertebrate Site Register (ISR) compiled by the JNCC.

2.10 When undertaking a desk study and reporting the results it should be recognised that the quality of ecological data from different sources is highly variable (Wyatt, 1991a; 1991b). Typical criticisms include the lack of information on when a survey was undertaken, the type of survey method(s) used (if any) and the overall competence of the ecologists carrying out the work. Where such gaps in information exist, or the quality of data is suspect for other reasons, an on-site survey may be necessary to update and/or verify the coverage and accuracy of previous surveys and collected data. Within an Environmental Statement the survey date and reliability of any existing information used in the assessment should also be clearly stated.

Both badgers and their setts are protected by law. Despite this they are threatened by digging and baiting in many areas, and sett locations should remain confidential

TABLE 1 STATUTORY AND NON-STATUTORY SITE DESIGNATIONS

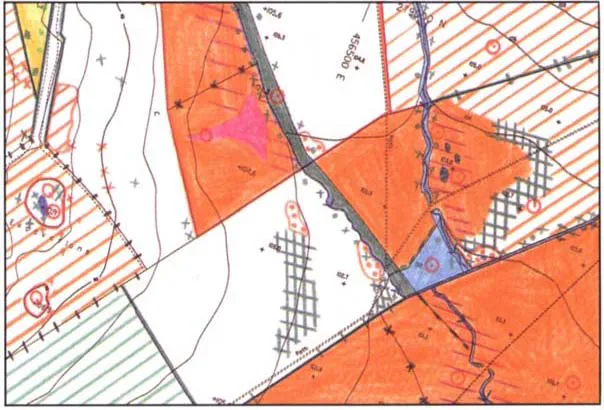

EXTENDED PHASE 1 HABITAT MAP WITH TARGET NOTE

EXAMPLE TARGET NOTES

8

Strip of broadleaved woodland with beech, sycamore and oak over scrub of hazel and hawthorn and a ground flora including wood sorrel, male fern and dogs mercury. Several mature oak and beech have woodpecker holes, loose bark and occasional hollow branches: hence potential for bats and hole nesting birds. Numerous piles of dry deadwood where ground and stag beetles were found. Singing nuthatch and yellowhammer present.

2

Marginal vegetation includes tufted hair grass, soft rush, ragged robin and great willow herb with scattered scrub of hawthorn dragonflies, hoverflies, bush crickets and stoneflies present.

10

Disused quarry with a small shallow-sided pond and scattered scrub including willow, hawthorn, bramble and gorse. The pond has marginal vegetation including soft rush, great willow-herb; young newts also seen, and tracks in the mud included deer (muntjac) and moorhen. The quarry sides are rich in bryophytes and lichens and have ferns including lemon-scented fern, hard fern and lady fern.

Example of a Phase 1 map(JNCC 1993) with Extended Target Notes

2.11 Consultations with the general public are also beneficial for identifying issues of local concern, and can on occasions reveal different issues from those initially identified by technical experts.

2.12 During the above consultations such issues as client confidentiality and limited access to certain information (eg the location of badger setts) should be taken into account.

2.13 Recognised sites of nature conservation interest (statutory and nonstatutory) which are within or near to areas likely to be directly or indirectly impacted, should be identified within an Environmental Statement and the main reasons for their designation outlined. A minimum area of search of a 2km radius around the development site is usually appropriate for obtaining information, although this may need to be extended where the impacts may be over a much larger area (eg air quality impacts of power stations).

2.14 The main types of site designations that may need to be considered within a baseline description are listed in Table 1. The list includes statutory and non-statutory designations since many planning authorities now have policies aimed at protecting local sites of conservation interest as well as nationally important statutory sites and protected species. Furthermore, it is more likely that non-statutory sites for nature conservation will be encountered in an EA than higher tier sites, such as NNRs and SSSIs, which ideally have been excluded at the site selection stage of an EA.Collis and Tyldesley (1993) provide a useful review of the existing status, policy framework and evaluation crit...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Summary

- Part One

- Part Two

- Part Three

- Part Four

- Abbreviations

- References

- Appendix One

- Appendix Two

- Appendix Three

- Appendix Four

- Appendix Five

- Appendix Six

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Guidelines for Baseline Ecological Assessment by The Institute of Environmental Assessment in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.