![]()

Part I

The nature of psychosis

![]()

Chapter 1

The recognition and optimal management of early psychosis

Applying the concept of staging in the treatment of psychosis

Patrick D. McGorry

EARLY PSYCHOSIS: A NEW REFORM PARADIGM

The best progressive ideas are those that include a strong enough dose of provocation to make its supporters feel proud of being original, but at the same time attract so many adherents that the risk of being an isolated exception is immediately averted by the noisy approval of a triumphant crowd.

(Kundera 1996:273)

Over the past decade, there has been a growing sense of optimism about the prospects for better outcomes for schizophrenia and related psychoses, and this has achieved the status of a ‘progressive idea’. This has disturbed some (for example, Verdoux 2001) who have urged caution in proceeding with reform. However, while there is a sociopolitical dimension to all successful reform, this one has an increasingly solid basis in evidence. Clinicians and policymakers in particular are enthusiastic about reform based on this idea because of the sound logic behind it and the unacceptably poor access to and quality of care previously available to young people with early psychosis, and are encouraged by the increasing evidence that better outcomes can be achieved. The rationale for, and extent of, this reform is described in Edwards and McGorry (2002) and the latest evidence is reviewed in a balanced manner by Malla and Norman (2002). There has also been considerable resistance and scepticism which helps to keep the reform process ‘honest’. In this chapter I will summarise this evidence and provide guidelines for its clinical application.

Key drivers of this paradigm are the special clinical needs of young people at this phase of illness, the iatrogenic effects of standard care and a range of secondary preventive opportunities (Garety and Rigg 2001). This is especially clear when the clinical care of first-episode and recent-onset patients is streamed separately from chronic patients, something which is still difficult to engineer and sustain (McGorry et al. 1996). The key failures in care are: prolonged delays in accessing effective treatment, which thus usually occurs in the context of a severe behavioural crisis; crude, typically traumatic and alienating initial treatment strategies; and subsequent poor continuity of care and engagement of the patient with treatment. Young people have to demonstrate a severe risk to themselves or others to gain access and a relapsing and chronically disabling pattern of illness to ‘deserve’ ongoing care. These features are highly prevalent in most systems of mental health care, even in developed countries with reasonable levels of spending in mental health.

The increasing devolution of mental health care into community settings has provided further momentum, as has a genuine renaissance in biological and psychological treatments for psychosis. Exponential growth in interest in neuroscientific research in schizophrenia has injected further optimism into the field, with a new generation of clinician-researchers coming to the fore. Several countries have developed national mental health strategies or frameworks which catalyse and guide major reform and mandate a preventive mindset and linked reform (WHO 2001). Around the world an increasingly large number of groups have established clinical programmes and research initiatives focusing on early psychosis, and it now constitutes a growth point in clinical care as well as research (Edwards and McGorry 2002). This reform differs fundamentally from previous reforms (such as deinstitutionalisation) in being much more evidence-based, and also in its integration of biological, psychosocial and structural elements of intervention.

Early intervention means early detection of new cases, shortening delays in effective treatment, and providing optimal and sustained treatment in the early ‘critical period’ of the first few years of illness (Malla and Norman 2002). Even on the basis of our existing knowledge, substantial reductions in prevalence and improved quality of life are possible for patients, provided societies are prepared to pay for it. However, this has not occurred, despite the development of effective treatments (Hegarty et al. 1994; Jablensky et al. 1999), because we have so far failed to translate these advances to the real world beyond the randomised controlled trial. Early intervention, with its promise of more efficient treatment through an enhanced focus on the early phases of illness, is an additional prevalence and burden reduction strategy, which is now available to be widely tested and, if cost-effective, to be widely implemented. This is hardly a radical goal and would be non-controversial in other areas of healthcare where primary prevention remains out of reach (for example, diabetes and many cancers).

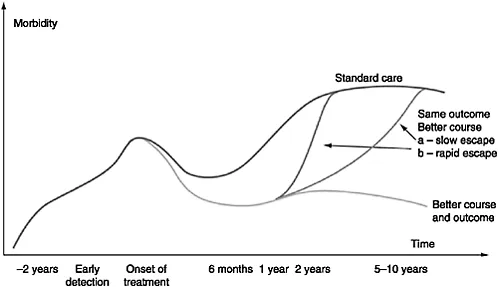

While evidence is a critical element, how much evidence is required before a change in practice is warranted? For asymptomatic patients with increased risk, the onus is clearly on avoiding harm, with attempting to reduce risk as a secondary goal. When patients become symptomatic and impaired, however, the dynamics change. In deciding where the onus of proof should lie here, we should be very clear that the alternative to early and optimal intervention is delayed and substandard treatment with all its human (and inhumane) consequences (Garety and Rigg 2001; Lieberman and Fenton 2000). Even in developed countries, as consumers and carers will readily attest, the timing and quality of standard care is relatively poor, very much a case of ‘too little, too late’. In developing countries, a significant proportion of cases never receive treatment (Padmavathi et al. 1998). While we do need evidence, there are obvious additional clinical and commonsense drivers for the provision of more timely and widespread treatment of better quality (see Figure 1.1).

EARLY INTERVENTION IN THE REAL WORLD: CONCEPTS, EVIDENCE AND CLINICAL GUIDELINES

Mrazek and Haggerty (1994) have recently developed a more sophisticated framework for conceptualising, implementing and evaluating preventive interventions for mental disorders which supersedes the primary, secondary and tertiary prevention model. This translates into a staged model of intervention for psychotic disorders.

Universal preventive interventions are focused upon the whole population while selective preventive measures are aimed at asymptomatic high-risk subgroups of the population. Indicated prevention is concerned with subthreshold symptoms which confer enhanced risk of a more severe disorder. Early intervention can be defined as indicated prevention, early case detection and optimal management of the first episode of illness and the subsequent critical period.

Prepsychotic intervention

This is a form of indicated prevention and is currently the earliest possible phase for preventive intervention in psychosis (Mrazek and Haggerty 1994). However, at present it remains a research focus, even though clinical guidelines have been developed to underpin a safe and appropriate clinical response to young people presenting for treatment with potentially subthreshold or prodromal symptoms (Garety and Rigg 2001), since these are distressing and disabling (Häfner et al. 1999; Yung et al. 1996). Much of the disability and collateral damage associated with psychotic disorders develops during this complex and confusing period and sets a ceiling for recovery, thus influencing the social course of the disorder (Häfner et al. 1999). In fact, subthreshold symptoms constitute a risk factor in their own right for more severe disorders (Eaton et al. 1995). Since universal and selective prevention remain out of reach at present, indicated prevention marks the current frontier of prevention research in psychotic disorders (Mrazek and Haggerty 1994). Notwithstanding the neurodevelopmental theory of schizophrenia, the illness is relatively quiescent during childhood (Jones et al. 1994) with the emergence in adolescence or early adult life of symptoms and disability which can be used to predict full-threshold disorder (Klosterkötter et al. 2001; Yung et al. 2004). The idea of intervening at this stage of illness raises conflicting concerns. With the passage of time, some of these cases will be seen to have been manifesting an early form of the disorder in question, and the subthreshold clinical features will then turn out to have been prodromal (a retrospective term). On the other hand, others will not undergo transition, and will therefore constitute ‘false positives’ for the disorder in question. This has caused concerns about the effects of labelling and unnecessary treatment (McGorry et al. 2001; Schaffner and McGorry 2001).

Following a series of initial naturalistic studies which created more accurate operational criteria for ultra high risk (UHR; Yung et al. 2004), a recent randomised controlled trial in this clinical population has shown a significant reduction in transition rate to psychosis for patients receiving specific treatment comprising very low dose risperidone (1–2mg/day) and cognitive therapy, in comparison to non-specific treatment comprising supportive psychotherapy and symptomatic treatment (McGorry et al. 2002). Such patients must be distinguished from a subgroup of the general population who report isolated psychotic symptoms in the apparent absence of distress, disability or progressive change, and who do not desire assistance (McGorry et al. 2001; Van Os et al. 2001).

Further research is urgently required to clarify the range of treatments which will alleviate distress and disability and reduce the risk of subsequent psychosis in help-seeking UHR patients. While this evidence is being assembled, if people present with a potentially incipient psychosis, there may often be a need for a clinical response. What should the clinician do when approached by a young person, or by the family of a young person, who appears to be at ultra high risk?

For those meeting the criteria for UHR (McGorry et al. 2002; Yung et al. 2003), the offer,...