- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Thinking Through the Skin

About this book

This exciting collection of work from leading feminist scholars including Elspeth Probyn, Penelope Deutscher and Chantal Nadeau engages with and extends the growing feminist literature on lived and imagined embodiment and argues for consideration of the skin as a site where bodies take form - already written upon but open to endless re-inscription.

Individual chapters consider such issues as the significance of piercing, tattooing and tanning, the assault of self harm upon the skin, the relation between body painting and the land among the indigenous people of Australia and the cultural economy of fur in Canada. Pierced, mutilated and marked, mortified and glorified, scarred by disease and stretched and enveloping the skin of another in pregnancy, skin is seen here as both a boundary and a point of connection - the place where one touches and is touched by others; both the most private of experiences and the most public marker of a raced, sexed and national history.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Skin surfaces

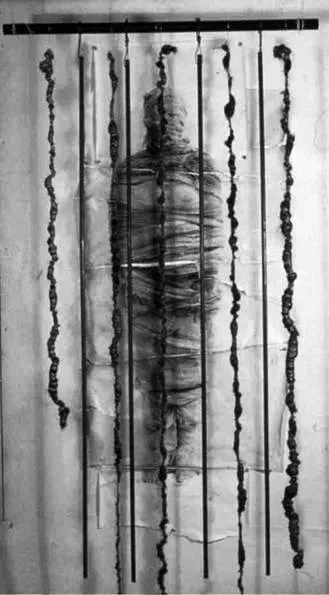

Frontispiece 1 ‘Instructions of the Body’

Toned photographic mural print with oil, steel bar and braided hair, from installation Writ(e) of Habeus Corpus, 5 ft × 5 ft Susan McKenna and Elizabeth Hynes

Toned photographic mural print with oil, steel bar and braided hair, from installation Writ(e) of Habeus Corpus, 5 ft × 5 ft Susan McKenna and Elizabeth Hynes

1

Cut in the body

From clitoridectomy to body art

Renata Salecl

How can one explain the fact that today in the same quarter of New York one finds youngsters who decorate their skin with body piercing, artists who use body mutilation as a form of art and African immigrants who practice clitoridectomy? The latter are usually fully integrated into Western society, that is, they work or go to school, they participate in public life and so on while still practising traditional initiation rituals. In such forms of body mutilations as clitoridectomy, one does not find simply the repetition of premodern forms of initiation; the return to these forms of initiation should rather be understood as a way in which the contemporary subject deals with the deadlocks or antagonisms of so-called post-modern society. And some practices of body art, as well as the fashion for body-piercing and tattooing can be seen as another way of dealing with these deadlocks.

I will analyze the practice of clitoridectomy in comparison with the masochistic turn in body art. I am not saying, however, that these forms of body transformation are in any way equivalent. What makes them comparable is the fact that they are two ways of dealing with the same question: What is the place of the subject in contemporary society?

Before making connections between these two practices, one needs to analyze different ways in which the subject identifies with the symbolic order in premod-ern, modern and post-modern societies. My intention, however, is not to trace the genealogy of these forms of society, but to take them as representing three different types of the subject’s relation to the so-called big Other, that is, the symbolic structure. If people today are returning to body painting or even to old forms of initiation, they are not simply copying some old cultural forms, they are reinterpreting these old forms in a new way. To understand this reinterpretation one first needs to analyze the original meaning of such initiation rituals as clitoridectomy.

Initiation and individualization

The ritual of clitoridectomy in the developing world is a topic that from time to time attracts the attention of the Western media and provokes almost universal admonishment from the public.1 There tend to be two types of reaction to clitori-dectomy. First, those who defend universal human rights are for strict prohibition of this ritual; and second, those who insist on the right to cultural differences usually still oppose clitoridectomy while stating that, however appalling they may find the practice, Westerners have no right to impose their standards on nonWestern cultures. Things get even more complicated when the Westerners realize that the rituals of clitoridectomy are performed not only in Africa or Asia, but also among the immigrants in the middle of New York, London, Paris. Here the legal prohibition of the ritual has no real effect, since clitoridectomy is never performed as a public act, but as a secret ritual. From the Western point of view, it is shocking that something like this happens in democratic societies.2 And it is also surprising that the development of global capitalism has not contributed to the extinction of clitoridectomy; on the contrary, in some countries the practice has become even more widespread in recent years. How can we explain this fact?

Women from the ethnic groups that support such initiation rites usually claim that this practice is part of their ethnic identity and has been performed by their ancestors, and that by carrying on with the initiation rituals they are essentially contributing to the survival of their tradition. When the members of such ethnic groups migrate to the West, they insist on their right to protect their identity through the performance of clitoridectomies. Women also claim that if they have not been initiated via clitoridectomy they cannot get married; and mothers who submit their daughters to this ritual usually state: ‘If it was good for me, it will also be good for my daughter.’

While Westerners fear that the habits of immigrant non-Westerners will shatter the Western way of life, the immigrants complain that the Western states’ prohibition of certain initiation rituals endangers their ethnic identity. It is thus not only Westerners who see the danger of the erosion of their culture in others (that is, the immigrant cultures); the immigrant groups also perceive themselves as endangered by the dominant Western cultures.

The case of clitoridectomy creates many dilemmas that go far beyond a simple decision as to whether one is against or in favour of this ritual. The question is: What role does clitoridectomy play in the formation of women’s sexual identity and how essential is this ritual for transmission of sexual norms from generation to generation? A further implicit question is: How does sexual difference inscribe itself in pre-modern and in modern societies, and how is one to understand a return to the body mutilation that occurs in post-modern society, for example in the case of some practices of body art?

Let me first summarize the explanations given by the supporters of clitori-dectomy as to why this ritual needs to be preserved. Although different ethnic groups usually justify clitoridectomy with different mythologies, one can make some basic comparisons. A widespread belief is that clitoridectomy assures women’s fertility. Various mythologies take the clitoris as something impure and dangerous for the future child. The clitoris is also taken as a rival to a man’s phallus. In Ethiopia, for example, one finds a belief that the uncut clitoris grows to the size of a man’s penis and thus prevents insemination. And the Bambara from Mali claim that a man who has intercourse with an uncircumcised woman might die, since the clitoris produces poisonous liquid. They also believe that at the time of birth one finds in the child both female and male traces. The clitoris is the trace of the male in the female and the prepuce is the trace of the female in the male. In order to clearly define the child’s sex, one therefore needs to extinguish the trace of the opposite sex via male and female circumcision.

Other justifications for clitoridectomy stress the importance of group identity. A woman who is submitted to this ritual becomes the equal of other women in her ethnic group–she is thus accepted in her community. The circumcised woman finds ‘the feeling of pride in being like everyone else, in being “made clean”, in having suffered without screaming’.3 For women, to be different, i.e., unexcised or noninfibulated, produces anxiety: such a woman may be ridiculed and despised by the others, and she will also be unable to marry in her community.

Some ethnic groups also claim that clitoridectomy protects women from their excessive sexuality. This ritual thus makes women faithful. Since excised women are supposed to be less sexually demanding, men can have many wives and keep them all satisfied. Others argue the opposite: the excised woman is supposed to be more inclined to have extramarital affairs, since she is always sexually unsatisfied. But, a very common position is that clitoridectomy helps to retain a woman’s virginity, which is especially important in the communities that make virginity the absolute prerequisite of marriage and in which women’s extramarital affairs are strongly condemned.

Some defenders of clitoridectomy also claim that this ritual needs to be understood as an aesthetic practice: the infibulated woman’s sexual organ is supposed to be much more attractive than the noninfibulated one. And the most beautiful organ is the one that, after the scar is healed, feels smooth like a palm.4

Why do women who are submitted to the torturous practice of clitoridectomy not rebel against it, why do they calmly accept mutilation of their genitals, and why do they force their daughters to do the same? The problem is not simply that women live in patriarchal societies in which they have no power to express their disagreement with the rituals. Many cultures that perform clitoridectomy are not classical patriarchies–in some cultures men are even perceived as quite powerless (see Heald 1994; Bloch 1986)–and often much authority is in the hands of the older women, who are cherished as authority figures and as guardians of tradition, which is why these women are entrusted with the task of performing the ritual of clitoridectomy. The dilemma of why women support clitoridectomy thus primarily concerns the position the subject has in his or her culture, that is, the way the subject is entangled in his or her community.

Max Horkheimer (1972) pointed out how, with the advent of the Enlightenment type of patriarchal family, one can discern a process of individualization that does not exist in the pre-modern family. The modern subject is, of course, linked to his or her tradition, family, national community, but this tradition is no longer something that fully determines the subject and gives him or her stability and security. The modern subject is expelled from his or her community–this subject is an individual who has to find and reestablish his or her place in the community again and again. That modern society no longer stages the ritual of initiation means that the subject must ‘freely’ choose his or her place in the community, although this choice always remains in some way a forced choice. As we know from psychoanalysis, the subject who does not ‘choose’ his or her place in the community becomes a psychotic–a subject who feels themselves external to the community yet is not barred by language.

But this forced choice to become a member of the community also enables the subject to experience some actual freedom, for example, to reject the rituals of his or her community. Only when the subject is no longer perceived as someone who essentially contributes to the continuation of his or her tradition and is completely rooted in his or her community does the moment emerge when the subject can distance himself or herself from this community, for example, by criticizing its rituals. Western feminists justly take clitoridectomy to be a horribly painful practice. However, one can arrive at such position only after going through the process of individualization, that is, only when the subject has already made a break with his or her tradition.

When we say that in pre-modern society subjects are not yet individualized and are thus unable to distance themselves from the tradition, this does not mean that when people support clitoridectomy today they are falling back to the level of pre-modern family organization. On the contrary, the return to old traditions needs to be understood as a way subjects deal with the deadlocks of the highly individualized contemporary society. Thus, when people propagate old initiation rituals they are not simply nostalgic for the past or unable to oppose their tradition (usually they are quite willing to give up many other rituals and prohibitions), but rather they are trying to find some stability in today’s disintegrating social universe.

There are various ways subjects deal with individualization in contemporary society. A young punk, for example, seems to respond to individualization by taking it to the extreme: he or she adopts an ultra-individualized stance and constantly searches for new decorations for his or her body to create a unique image. Such a punk makes an effort to dress differently from the dominant fashion trends, but then he or she also strongly identifies with some peer group. The punk’s response to individualization is thus finally a formation of another group ideology. Although this ideology encourages people to look different from each other, it none the less quickly forms new fashion codes. In contrast, an African immigrant might respond to radical individualization by strongly identifying with his or her ethnic tradition. In this case, too, group identity, paradoxically, appears as a solution to the difficulties of individualization. If individualization first happens when the subject makes a break with tradition, the deadlocks that accompanies individualization incites either a return to tradition or a formation of some new group identity.

The impotence of authority

It is well known that both types of initiation–male circumcision and clitori-dectomy–are ways in which pre-modern societies mark sexual difference. In these societies, biological sex is deemed not enough to ensure their reproduction.

It is the symbolic cut made by the law, that is, by language, that enables the continuation of tradition. The pre-modern society imposes all kinds of prohibitions and rituals that make a social being out of the human being. But in this society the symbolic cut in the body, the inscription of the subject’s identity, occurs as something real. In the act of initiation, the subject receives a physical mark on his or her body, in most cases through circumcision but in some cases also through paint on the body or a tattoo. Anthropologists stress that initiation is an extremely traumatic event, especially if it happens in adolescence, since before being initiated the subject has no clear identity but after initiation the subject becomes heavily burdened by his or her sexual function and is thus expected to perform in accordance to it.

The pre-modern subject may have doubts about his or her sexual identity, but the gesture of initiation is supposed to alleviate these doubts and, through the cut in the body, confirm the subject’s sexual identity. This mark on the body is therefore the answer of the big Other, of the symbolic structure, to the subject’s dilemma. In the case of the modern subject, we no longer have the inscription of sexual identity on the body, since it is enough that the subject is marked by symbolic castration in his or her inner self. (St Paul, for example, explains that Christians do not prescribe circumcision, because the subject is already cut in his or her soul.) In modern society, the big Other still has power, since socialization usually proceeds via submission to the symbolic law represented by the paternal authority. By contrast, in contemporary post-modern society, there has been a radical change in the organization of the family, which also entails a different relation of the subject towards the symbolic order: the return to the ritual of clitoridectomy as well as other forms of inscription on the body (even genital mutilation) in some practices of body art is not the answer to the big Other, but rather the subject’s answer to the nonexistence of the big Other.

Before dealing with this return to the cut in the body, let me first try to give a psychoanalytic account of clitoridectomy. The ethnic groups that support this practice usually claim that by cutting the female genitals they protect the woman’s honor and thus show respect for her. The cultures that perform clitoridectomy perceive Western cultures as degenerate, since they do not honor women. Here, we have two totally different points of view about what women’s honor is: for the Westerners, clitoridectomy is an act that mutilates women and violates human rights, and thus also dishonors women; while for people who embrace clitoridectomy, the absence of this ritual devalues women.

How would psychoanalysis explain this logic of honor and respect for women? Freud dealt with the problem of female shyness, which he linked to the lack or the absence of a phallus. By being shy, the woman tries to cover the lack and to avert the gaze from it. However, this shyness has in itself a phallic character. So it can be said that the very lack of the phallic organ in woman results in the phallicization of her whole body or a special part of the body; and covering up this part of the body has a special seductive effect.

There is no significant difference between women’s shyness and their honor: ‘The respect for women means that there is something that should not be seen or touched’ (Miller 1997: 8). Both, shyness and respect, concern the problem of castration, the lack that marks the subject. The insistence on respect is a demand for distance, which also means a special relation that the subject needs to have towards the lack in the other.

Freud thought of woman as the subject who actually lacks something, which means that in her case castration was effective. As a result of this, the woman has Penisneid (penis envy). In psychoanalytic practice, women’s ‘deprivation’ appears in many forms: as a fantasy of some essential injustice, as an inferiority complex, as a feeling of nonlegitimacy, as a lack of consistency or a lack of control, or even as a feeling of body-fragmentation. The Freudian solution for this ‘deprivation’ was maternity. But for Lacan, women’s relation to the lack is much more complicated: the problem of femininity is not linked simply to having or not having a penis. The lack concerns the subject’s very being–both a man and a woman are marked by lack, but they relate differently to this lack. Woman does not cover up the lack by becoming a mother, since for Lacan the problem of the lack cannot be solved on the level of having but only on the level of being. Motherhood is not a solution to woman’s lack, since there is no particular object (not even a child) that can ever fill this lack.

Respect, therefore, has to do with the subject’s relation to the lack in the other, which also means that respect is just another name for the anxiety that the subject feels in regard to this lack. The respect for the father, for example, needs to be understood as a way in which the subject tries to avoid the recognition that the father is a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Transformations: Thinking Through Feminism

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Plates

- Notes on contributors

- Series editors’ preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Dermographies

- Part I: Skin surfaces

- Part II: Skin encounters

- Part III: Skin sites

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Thinking Through the Skin by Sara Ahmed, Jackie Stacey, Sara Ahmed,Jackie Stacey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Sociologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.