eBook - ePub

Growing Up and Growing Old in Ancient Rome

A Life Course Approach

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Throughout history, every culture has had its own ideas on what growing up and growing old means, with variations between chronological, biological and social ageing, and with different emphases on the critical stages and transitions from birth to death.

This volume is the first to highlight the role of age in determining behaviour, and expectations of behaviour, across the life span of an inhabitant of ancient Rome. Drawing on developments in the social sciences, as well as ancient evidence, the authors focus on the period c.200BC - AD200, looking at childhood, the transition to adulthood, maturity, and old age. They explore how both the individual and society were involved in, and reacted to, these different stages, in terms of gender, wealth and status, and personal choice and empowerment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Growing Up and Growing Old in Ancient Rome by Mary Harlow,Ray Laurence in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

Ageing in antiquity

The fact of the matter is that there is a general lack of vital statistics from the ancient world

(Parkin 1992: 59)

Human ageing and the life course

Our intention in writing this book is to open the subject of age and the Roman life course for discussion. What is here is not our last word on the subject, but is written with the intention of making this area of historical research accessible to students at university and to those outside the subject of Classics, as well as to informed ancient historians. From the 1980s onwards, there has been a concerted effort to search for or discover the Roman family (Bradley 1991; Dixon 1992; Rawson 1986, 1991, 1997). This work has defined the family at Rome through a careful study of the literature, epigraphy and above all law. At the same time, Richard Saller (1994) simulated the structure of the Roman system of kinship to elucidate the changing structure of the Roman family according to the age of an individual. This work has provided the basic structure for our discussion of changes in the age of individuals at Rome. Our concern, though, is not with the family itself but with the individual and the view of the individual’s actions according to their position in the life course. What we wish to identify are underlying codes of behaviour or the expectations of others when viewing the actions of a person according to their age (see Ryff 1985 on the subjective experience of the life course). We emphasise the role of the individual and individual action, because we wish to be aware of variation in the life course. There is little surviving evidence for the reconstruction of the life courses of those who were not from the elite, and it has to be recognised that the recovery of the experience of age in antiquity is limited to this influential group. However, the experience of age and ageing would vary within this group itself according to the variation of family structure that was shaped through the birth and death of its members.

The focus is on the experience of the individual acting within the expectations of his or her family and the observation of outsiders. Here, we attempt to resist the temptation of creating a standard life course from birth to death, in favour of an emphasis on different experiences in the relationship between independent adults and dependent young and old. This variation is apparent in cases known to both the authors and readers of this volume. For example, a brother and sister were born two years apart. The sister married at twentyone and had three children before she was thirty; whereas the brother married at the age of forty-two and had his first child. Technically, both the brother’s and sister’s children are the next generation, but in terms of chronological age there is a discrepancy of twenty-one years between the cousins. Hence, within an individual family, there is a massive variation of the age of parenting as well as the age of its members. Many of these variations are hidden by social categories, for example mother, father, granny or grandpa, that are the signifiers of the construction of identity regardless of chronological age. Hence, to study the life course of a society we need not depend entirely on chronological age for the construction of the characteristics of the individual; instead these are seen in conjunction with the changing familial roles of that person.

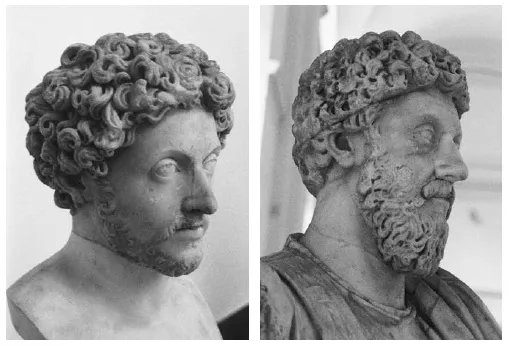

Plate 1.1 Marcus Aurelius: young and old. The first image shows Marcus Aurelius as a young man with a recently grown beard, whereas the second image displays him in old age with a full beard, lined eyes and a furrowed brow.

Today, ageing is seen as the key subject in the human sciences and humanities. The reason for this is partly that the changes in the demographic structure of the West have resulted in a significant increase in the number of old people as a proportion of the total population in the last fifty years. At the same time, our characterisation of other age-related categories has been questioned. For instance, the construction of children as innocent and protected is hard to maintain in the light of a series of media stories that involve physical violence and assault by minors. It is no longer possible to simply accept that the categories child, adolescent, adult and old simply exist across time. Just as the categories female and male are culturally constructed to create a difference and to preserve a male dominance in terms of power; children, adolescents and the old are defined in a similar fashion as not adult or in a state of becoming or unbecoming adult. How these categories are defined can vary across cultures and through time. Hence, to our mind, it is imperative for ancient historians to join the debate on ageing for the benefit of their own subject and to make a contribution to the debate that is occurring in the social and biological sciences (e.g. Pilcher 1995; Medina 1996). Moreover, it is now recognised that the modern West’s concepts and social expectations have been shaped through the reception and adoption of ideas rooted in antiquity (Wyke and Biddiss 1999). The modern conception of age is no exception, but discussion of this topic would fill at least another volume.

The term life course needs some explanation. It encapsulates the temporal dimension to life that begins at birth and ends in death with numerous stages and rites of passage along the way. However, the life course is not simply a description of biological ageing. It is culturally constructed and need not exactly follow biological or mental development in humans. Every culture has its own version of the life course, with a different emphasis on critical stages and transitions. Thus, we are born not simply into the social structure of a society, but also into the life course of that society. The individual follows the life course of a society, but their reaction to it or involvement in the stages can vary according to status, gender, personal choice and empowerment. In other words, the agent will act within the structure of the life course to a set of expectations of that agent by others within that society. Here, we follow Giddens’ structuration theory (1984: 1–40) that empowers individuals differently according to their place within the structure of society with respect to their wealth, status and cultural perspective. The life course is very much a cultural perspective and part of an organising structure of a society, but the experience of ageing is also strongly influenced by the wealth or status (including gender) of the individual at Rome.

Life cycle is another term that we need to clarify. It is a term used by biologists to describe the events from birth through to death and the production of the next generation of a species. This can be used to describe the life cycles of anything from slime moulds to mammals. We need at this point to refer to the work of Bonner (1993), a biologist who spent a life time studying the seven-day life cycles of slime moulds and who has lucidly investigated the wider frame of the life cycle. He suggests that the individual adult can be viewed in a number of ways, most easily in terms of their stage of life as adult as opposed to larva or pupa. But, in many ways, an individual in terms of a wider time frame is in fact part of a life cycle – a human is an individual within a succession of life courses or generations. Thus, we should view the individual life course as part of a succession of similar life courses that biologically and culturally reproduce a society through time. To us, this cumulative patterning of life courses is the life cycle of a society. Unlike the life course, it does not end with death but is reproduced in the next generation and has a fundamental link to what we commonly regard as the temporal frame of history or the longue durée.

Both the life course and the life cycle are terms that relate a human present to its past and future and can be seen as temporal structures to create meaning and certainty in the human perspective of existence. A person’s age within the life course sets out a position with reference to their past, and presents them with an expectation of future events. In fact, we would argue that the life course is an expected future at birth that structures a person’s aspirations whether parent or child. In contrast, the life cycle of generations creates a longer view of time, via ancestry back into the past and into the future with the presumption of future generations. What is created is a structure for the past and the future. In reality, life courses could be cut short through death at any stage. At Rome, relatively few survived to old age, but that did not prevent the development of an expectation of a life into old age. These conceptions of temporality were as significant as the day-to-day changes or the longue durée of change across several generations. At Rome, these were represented by the secular cycles of one hundred and ten years, and were celebrated with the expectation that no one would see the rites of this festival more than once (on the festival see Beard, North and Price 1998: 201–6). Importantly, within the festival, there was an emphasis on a new beginning – the expected future experiences of the young. Significantly, the life course was a means to reproduce the age and social structure of Roman society from one generation to another – i.e. from father to son or mother to daughter. It asserts the power of parents or adults over their children and other dependants, as well as gender roles. In turn, these children become adults and utilise the same techniques and structures for reinforcing their position and power within the family structure. It is therefore also a means to reinforce key ideological positions and to maintain certainty and the status quo. In other words, the life course was a technology of power to ensure a consistency in ideology and behaviour across the generations at Rome.

The book arises from recent scholarship on the family and gender in antiquity and, in fact, could not have been written prior to the investigation of this area over the last twenty years (notably Bradley 1991; Dixon 1992; Gardner 1986; Gleason 1995; Hallett and Skinner 1997; Kertzer and Saller 1991; Rawson 1986, 1991, 1997; Rousselle 1988; Saller 1994; Treggiari 1991a; Wiedemann 1989; Williams 1999). There had been a tradition of publication on the daily life of the Romans with an implicit comparison with the modern practices and family structures of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This comparison is at times crude, incorporating an assumption that we today have become more civilised than those at Rome. A slave society, with the spectacles of the amphitheatre and a lack of democratic freedom or women’s rights, is not to our cultural taste, even though the modern West views the culture of Rome as a key element in its own historical and cultural tradition. This has often led to the creation of Rome as a model horror into which our own society might descend. Alternatively, Rome has been used discursively as a means to promote discussion or to release anguish with reference to modern society. Few today would read Jerome Carcopino’s interpretation in his section ‘Feminism and Demoralisation’ in Daily Life in Ancient Rome without a wry smile. The ‘presentism’ of his views, which are personal, is easily identifiable. We as authors are very conscious of the need to control the comparative genre, which can produce explanations that identify a difference between Rome and ourselves. At the same time, although we see our analysis of the life course as relevant to the contemporary debate on human ageing, we wish to identify differences within the categorisation of the key stages of the life course: infant, child, puberty, adulthood and old age.

For those reading this book from beyond the discipline of Ancient History, we refer them in the first instance to Jo-Ann Shelton’s As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History (1988) and Jane Gardner and Thomas Wiedemann’s The Roman Household: A Sourcebook (1991) to gain access to primary evidence for human ageing at Rome. References in the text to classical sources follow standard conventions as listed in the Oxford Classical Dictionary: for example, Cicero’s Letters to Atticus is abbreviated as Cic.Att; the numbers following the reference give the paragraph or line number of the section referred to. The reader is strongly encouraged to examine these at first hand, either in translation or in the original language. These primary sources lie at the heart of our interpretation of ageing and the meaning of age at Rome. We hope that readers outside our subject will be able to see the primary evidence for themselves, evaluate our strategies of interpretation and contribute to future discussion within this field of study. We should also make it clear that the temporal period we are dealing with chronologically stretches from about 200 BC through to AD 200.

The seemingly natural categories of child, adolescent and elderly are all terms that identify individuals as not adult. They all signify states and stages of dependence, whereas an adult is seen as independent of their parents, and only becomes dependent upon their children in old age. The categories of the dependent and the independent individual seem to characterise age in order to assert the power of the adult over both young and old (Hockey and James 1993). The transition from one stage of life to another is culturally fixed. In Britain, children become independent when they are eighteen – they can vote, effectively claim welfare benefits, etc. However, this transition has little to do with their biological stage of development. The age of eighteen (the age of enfranchisement in Britain) occurs at the end of biological growth, but the age of sixteen (the minimum legal age of marriage and sexual activity in Britain) occurs at a chronological age beyond sexual maturity. This highlights how the categorisation of the stages of life does not follow a biological logic, but is constructed within the discourse of age and maturity. The contrast with ancient Rome here is quite striking. There, marriage for girls could occur before menarche at the age of twelve or thirteen, while for males it occurred well into their twenties. This comparison demonstrates a difference in the construction of the transition to a married state within the life course across cultures. Hence, at the outset of this book, it needs to be understood that there need not be anything biologically natural about the way we construct the different categories of infant, child, adolescent, adult and old.

Death and life

Ancient historians have a tendency to be interested not only in the things that can be known from the Roman world, but also in those things that cannot be known. A classic case is life expectancy two thousand years ago. At first sight there appears to be a wealth of data. The tombstones from across the Roman empire record the ages of the deceased they commemorate. For example, the parents of Hatera Superba record on her memorial that she died at the age of one year, six months and twenty-five days (CIL6.19159). The information is desperately personal, with the parents choosing to record even the number of days their daughter had lived. The age of death should not be seen as simply a statistic: it is far more than that. It is a cultural response to a daughter’s death. If she had died prior to teething at about six months, her parents would not have commemorated her life in the same way (Plin.HN7.68); similarly, if she had lived and married it would probably have been her husband who was mentioned in the inscription. Equally, other parents may not have commemorated their daughter’s death at this age with a monumental inscription. The point is that the funerary epitaph is personal, and refers to a specific instant in the life course of the deceased. This affected the way in which the individual was commemorated by their kin or loved ones.

These decisions about the commemoration of an individual cause the age of death as recorded on a funerary monument to be a personalised statement, which cannot be utilised statistically in combination with other inscriptions recording the ages at death to calculate a pattern of life expectancy. Ancient historians have suggested that if we were to find the average age of death recorded in funerary inscriptions across the empire we would then know the average life expectancy of the population (Parkin 1992: 5–8). However, the geographical variation across the Roman empire of such data suggested that what was recorded was a pattern of epigraphic commemoration that was culturally determined, rather than an actual pattern of longevity (Hopkins 1966). The epigraphic samples reveal a habit of age rounding to the Roman numeral V and X, presumably for reasons of typography and stonecutting. More importantly, the inscriptions expose patterns of commemoration that reveal the relationships of kin to the deceased, as Richard Saller (1994) has shown. These patterns, it should be stated, are intimately connected to the Roman conception of the life course and the stage of life of the deceased. For example, we find that parents predominantly commemorate sons until their twenties – after which commemoration by a wife becomes more prominent. Similarly, daughters were commemorated by parents almost exclusively until their mid to late teens at Rome. Subsequently, women in their late teens and twenties tend to be commemorated by husbands. Saller (1994: 32) suggests that this patterning within the epigraphic data points to a change in the life course, which identifies the age of marriage and the renegotiation of commemoration defined by marriage. Hence the funerary inscriptions inform us indirectly about the age of marriage, rather than being data for life expectancy. These inscriptions subtly encapsulate the stages of life and its association with kin and spouses, in combination with statements of chronological age.

The Romans conducted censuses of the population of the empire. The data taken town by town, region by region, province by province, were available to be perused by individual scholars. Pliny the Elder, in discussing human longevity, uses these data. He finds in the AD 73 census for the region of the Po plain (Region 8 of Italy) that fifty-four people had said they were a hundred years old, fourteen that they were a hundred and ten years old, two had announced that they were a hundred and twenty-five, eight were maintaining that they were in their hundred and thirties and three were adamant that they were one hundred and forty years old (HN7.162–3). These statements should not be seen as fact, but as classic cases of age exaggeration in census returns that are common today in the figures for the over eighty-yearolds. When broken down into the towns where these people lived, we can say that in many towns of the region there were usually one or two people who maintained they had already lived to a great age; exceptionally so in Veleia there was a concentration of eleven such individuals. The question remains, how long could a human being have lived in the Roman world? Modern life spans have a potential of being one hundred and fifteen years (Medina 1996: 10), but circumstances tend to reduce that life span via, for example, heart failure. In antiquity, people could in theory have lived for a similar length of time and Pliny is at pains to make this clear, with numerous examples of long-lived males and females in their nineties and hundreds (HN7.153–67). Galen, also, sees the maximum at one hundred and seventeen years (Remediis Parabilibus 3.14.56K). This implies that the life span in modern twentiethcentury humans and those living two thousand years ago is not necessarily so different. Where there is a difference is in the way a life span could be terminated at an earlier date. Today in Britain and the USA, we view the major threats to our own longevity as cancer, heart disease, AIDS, car accidents, etc. For those living in antiquity the focus would have been on a different variety of threats: famine and malnutrition, epidemics, sanitation related diseases and warfare (Parkin 1992: 93). The effect of these can be seen in the calculation of infant mortality in Rome compared to the USA today: in modern America the infant mortality rate is about ten per thousand, whereas in ancient Rome it is calculated at roughly three hundred per thousand. In other words in Rome infant mortality is thirty times that in the West today. Those living in ancient Rome could have lived into their hundreds as we can today: what was different was the risk to life, particularly in childhood. Hence, we would describe the population of the Roman world as one associated with a high death rate and a high birth rate.

Demography

A cultural approach to the life course needs to take account of how a society is structured by its demographic make up. In the late twentieth century in Western Europe and North America, there has been a significant increase in the proportion of the population over sixty years of age. This has had some impact on our cultural expectation of old age and has caused retirement at age sixty or sixty-five to be put into question. In the Roman world, the demographic structure into which an individual was born raised basic questions such as: how old were that person’s parents; were their grandparents alive; did he have or will he have had brothers and sisters? Equally, when were the major changes going to occur through that person’s life in terms of the life course: marriage, death, and the birth of offspring? These questions cannot be directly addressed via the evidence from the ancient world – after all, no ancient writer says: ‘generally the age of marriage is such and such in my home town’. Instead, we need to rely on cultural statements and interpret these statements in the light of the study of demography and the statistical simulation of population structures. This will not provide absolute data in itself, but will model the population trends that were likely to have resulted from the information we have.

The study of demography has since the 1950s been informed by what are called ‘Model Life Tables’. These vary according to the region, level of development, nature of life threatening diseases, and other variables in the modern world. To establish which of these tables would fit the ancient worl...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Location of the Life Course

- 3 The Beginning of Life

- 4 Transition to Adulthood 1

- 5 Transition to Adulthood 2

- 6 The Place of Marriage in the Life Course

- 7 Kinship Extension and Age Mixing Through Marriage

- 8 Age and Politics

- 9 Getting Old

- 10 Death and Memory

- 11 Age and Ageing in the Roman Empire and Beyond

- Appendix

- Bibliography