- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Caribbean is one of the premier tourist destinations in the world. Changes in travel patterns, markets and traveller motivations have brought about considerable growth and dramatic change to the region's tourism sector. This book brings together a high calibre team of international researchers to provide an up-to-date assessment of the scope of tourism and the nature of tourism development in the Caribbean. Divided into three parts, the book:

- gives an overview of existing tourism trends in the region

- addresses tourism development issues, including sustainability, ecotourism, heritage tourism, community participation, management implications, and linkages with agriculture

- considers future trends, including an assessment of recent world events and their impacts on tourism in the region, and future trends in terms of airlift, economic sustainability and markets.

A valuable resource for students of tourism and Caribbean studies, as well as governments, and national and regional tourism offices, this topical volume brings together excellent contributions to assess and analyze the state of the Caribbean tourism; past, present and future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tourism in the Caribbean by David Timothy Duval in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Trends in Caribbean tourism

1 Trends and circumstances in Caribbean tourism

David Timothy Duval

Introduction

The Caribbean has long been regarded as one of the world’s premier travel destinations. While the turbulent nature of global tourism has led to numerous changes in travel patterns, markets and tourist motivations, the extent and scope of tourism in the Caribbean has been substantial. While tourism in the Caribbean is by no means recent (Bryden 1973; Perez 1975; Sealey 1982), periods of economic instability in many island states in the region have effectively enhanced the relative importance of tourism as an alternative economic development strategy. Many island states in the Caribbean are particularly vulnerable to global economic volatility due to a reliance on world markets for various produced goods (Payne and Sutton 2001). Somewhat ironically, the notion of ‘smallness’, in reference to the economic position of island states in general, and the extent to which the Caribbean functions as a peripheral destination to global flows of economic activity, actually bears little resemblance to the degree to which the region is situated as a key vacation destination for literally millions of foreign travellers. While the Caribbean is economically marginalised, it also plays host to millions of tourists each year.

In light of turbulent economic conditions in many island states in the region, it is not surprising that the scope of the tourism sector in the region is substantial. By the 1990s, tourism in the region generated US$96 billion in expenditures per year and employed some 400,000 people (Gayle and Goodrich 1993). The World Travel and Tourism Council’s (WTTC) Tourism Satellite Account (WTTC 2001) indicated that, region-wide, tourism accounted for approximately 2.5 million jobs or 15.5 per cent of total employment in 2001, and contributed 5.8 per cent (or US$9.2 billion) to the region’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 2011, tourism is expected to contribute some US$18.7 billion, or 6 per cent of total GDP (WTTC 2001). The significance of tourism in the Caribbean effectively mirrors, and even trumps, the importance and scope of tourism worldwide. For 2001, for example, the World Tourism Organization (WTO) estimated 693 million tourist arrivals worldwide and US$463 billion in internationaltourism receipts (WTO 2002). While worldwide visitor arrival growth4 David Timothy Duval between 1990 and 2000 increased an average of 4.3 per cent, average annual growth in arrivals to the Caribbean increased 4.7 per cent (Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) 2002a) (Table 1.1). Despite the economic significance of tourism in the region, however, concerns over the degree of dependency created are often raised (Bryden 1973; Erisman 1983). Holder (1988) has even suggested that tourism in the Caribbean is environmentally dependent given the extent to which it relies on the available natural resource base. Further, Wilkinson (1989) argues that, with the almost inevitability of tourism as a crutch for economic development in certain localities, the risk, or ‘folly’, of mismanagement and failed integration within other sectors can often be considerable.

By extension, and despite the sizeable economic importance of tourism in the region, the tangible benefits of tourism have come under intense scrutiny (e.g. Archer and Davies 1984; Wilkinson 1989). At issue, in the first instance, is whether the economic benefits of tourism are realised at the local level, as substantial foreign ownership of service providers such as airlines and hotels may often mean a significant degree of leakage (Wilkinson 1989). Further, Wilkinson (1996) questioned the difference between current and real visitor expenditures in the region. Using the data on visitor numbers and expenditures combined with consumer price index shifts for the Bahamas, Wilkinson (1996: 33) noted that: ‘In real terms, the Bahamas is only slightly better off in 1993 than it was in 1971 in total visitor expenditures.’

Criticism over tourism is not only limited to economics. The negative biophysical impacts of tourism development have received attention in both the academic literature (Weaver 1995; Wilkinson 1989) and among governments and wider regional bodies. Critics cite, for example, pollution and damage to marine environments as a result of mass tourism in the region. Social impacts have also been addressed in the context of the overall community value gained from tourist expenditures (Wilkinson 1999) and with respect to indigenous cultural environments packaged and commodi-tised for foreign tourists (e.g. Slinger 2000). The question, then, is whether tourism in the Caribbean is, to borrow from Brown (1998), a blight or a blessing.

Table 1.1 Worldwide and Caribbean tourist arrivals (1990–2000)

The Caribbean–physiographic, economic and political aspects

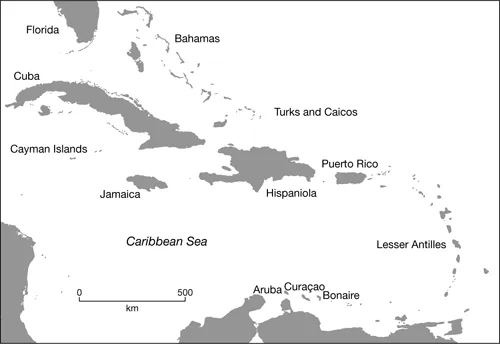

At the outset, and in the spirit of Harrigan’s (1974) assertion that it is ‘often necessary to have a definition handy’, it is important to set forward a geographic definition of the Caribbean that will be followed throughout this book. Those island states considered can perhaps best be referred to as the ‘insular Caribbean’. In other words, of interest are those island states stretching from Cuba to Trinidad and Tobago (Figure 1.1). Consequently, the northern coastal countries of the South American mainland (Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela) are outside the purview of this book. Similarly, while Belize, Cozumel and Cancun fall under the purview of the Caribbean Tourism Organization, they have been broadly excluded from direct consideration in this volume. The reason for excluding these destinations is that recent analyses (e.g. Clancy 2001; Lumsdon and Swift 2001) have already offered adequate coverage.

Figure 1.1 Map of the Caribbean

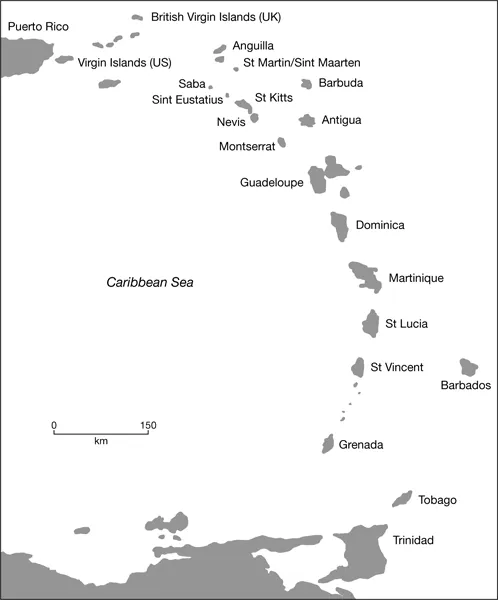

As defined here, the Caribbean region (Figure 1.1) can be separated into two broader subregions. The Lesser Antilles (the ‘eastern Caribbean’ or ‘southern Caribbean’) geographically encompasses the United States and British Virgin Islands in the north to Trinidad and Tobago in the south (Figure 1.2).The Greater Antilles (the ‘western Caribbean’ or ‘northern Caribbean’) incorporates Jamaica, Puerto Rico, the island of Hispaniola (incorporating Haiti and the Dominican Republic), the Cayman Islands and Cuba. As Table 1.2 indicates, both the size of the population and the total land area occupied by individual island states in the region vary considerably.

Several geographic anomalies exist in the region. The Bahamas, while situated north of Cuba, are not normally classified as either a Lesser or Greater Antillean island cluster. The Netherlands Antilles, as a political designation, is defined by two geographic groups in the region: one group incorporates the islands of Curaçao and Bonaire (see Figure 1.1) in the southern Caribbean Sea, while the second group is comprised of Saba, Sint Maarten (the Dutch part of the island of St Martin) and Sint Eustatius. Now a kingdom of the Netherlands, Aruba was once part of the Netherlands Antilles but seceded in 1986. Finally, the overseas territory of Bermuda, a UK dependency consisting of a clustering of over 100 coral reefs and small islets, exhibits a climate that is not unlike its Caribbean neighbours, yet it is located almost directly east of the state of North Carolina.

The Lesser Antilles can be subdivided geographically into the Leeward Island group and the Windward Island group. The Leeward group encompasses the British and US Virgin Islands south to, and including, Guadeloupe, while the Windward group is comprised of Dominica, St Lucia, Barbados, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and Grenada. While Trinidad and Tobago are not normally included in the Windward Island characterisation, they are often included in the wider ‘Lesser Antilles’ characterisation.

The geographic complexity exhibited through subregion designations in the Caribbean is equalled by the political variability found in the region. The Caribbean is home to British Commonwealth members, United States Commonwealth members, British dependencies, autonomous countries within larger kingdoms and independent republics. A number of island states in the Caribbean are independent sovereign nations, while several continue to retain political and economic dependency arrangements with colonial states. Regional political and structural bodies such as the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the Association of Caribbean States (ACS) and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) seek to enhance the economic status of the region on the world stage by offering blanket representation in both international and regional affairs. Theirefforts are crucial, if not difficult, as the economies of the various island states in the region are diverse. Trinidad and Tobago, for example, experienced real GDP growth of 7 per cent in 1999 as a result of strong overall performance in its energy sector (Commonwealth Secretariat 2001), while sugar and bauxite continue to be critical exports for Jamaica. Other economic activities include nutmeg and mace (Grenada), offshore finances (e.g. Aruba, St Lucia) and manufacturing and technology (e.g. Barbados). In 2000, Cuba observed significant growth in its mining sector and the resulting production of petroleum (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean 2001).

Table 1.2 Selected economic indicators of various Caribbean island states

Agriculture continues to be an important source of income for many island states. In the past four to five decades, arrowroot, sugar cane, coconut, indigo, spices and tobacco have been cultivated. While agricultural production continues to be important to the strength of many local economies, its share of the GDP of many island states is falling. In Dominica, for example, agriculture accounted for 24 per cent of GDP in 1985, yet by 1998 it had dropped to 20 per cent. Similarly, agriculture contributed 16 per cent of St Vincent and the Grenadines’ GDP in 1985, but by 1998 its share had fallen to 11 per cent (Commonwealth Secretariat 2001). Andreatta (1998) notes that, in anticipation of substantial changes to marketing regimes, non-traditional crops such as root crops, cucumbers, flowers, hot peppers, tomatoes and other non-banana tropic fruits are increasingly being cultivated.

Figure 1.2 Map of the Lesser Antilles

Despite such attempts at agricultural diversification, bananas comprise an important export commodity, particularly in the Windward Islands (Commonwealth Secretariat 2001). In the 1990s, however, the ability of some islands to effectively produce banana crops for export to the European Union was threatened by challenges to the EU’s banana import regime (Payne and Sutton 2001). As a result, uncertainty over access to existing and future markets continues to shroud the banana cultivation in the Windwards. As Payne and Sutton (2001: 271) note, the lessons learned from the banana crisis point to the ability, or lack thereof, of small Caribbean states to function in the wider international economic arena:

The Caribbean, especially the smaller countries of the region, here find themselves particularly disadvantaged: marginalized in the development policy debate, side-lined in the corridors of power and handicapped by small size and economic dependence… the imperative to find development alternatives is the central issue facing the Windward Islands and, by analogy, other parts of the Caribbean with similar situations of domestically desirable, but internationally uncompetitive, agricultural, extractive, industrial and service sectors.

While part of the decreased emphasis on agricultural production can be attributed to an increasing amount of attention devoted to the development of tourism, the reality is that the production of, for example, rice, coffee, aluminum, bauxite, spices, petroleum and chemical products is often subject to substantial shifts in demand. Increased competition from other areas of the world, where the benefits of cheaper labour and larger economies of scale and scope are significant, has also played a role. For those reasons, and in the face of economic uncertainty, it is hardly surprising that many island states have taken notice of the sizeable growth in the world tourism sector.

Tourism in the Caribbean: some preliminary considerations

Modern conventional mass tourism (i.e. Turner and Ash’s (1976) ‘golden hordes’) began in the mid-twentieth century in the Caribbean. This form of tourism can, to a large extent, be characterised by undifferentiated products, origin-packaged holidays, spatially-concentrated planning of facilities, resorts and activities, and the reliance upon developed markets such as the United States, Canada and Britain. From a tripographic perspective, mass tourism in the Caribbean is commonly associated with cruise tourism and all-inclusive package holidays (largely incorporating resort enclaves (Freitag 1994)) (Conway 2002; Jayawardena 2002). With the growth in available leisure time across many developed countries (Shaw and Williams 2002), particularly in the form of patterned, yet temporally repetitive, holiday distributions, the dominant tourism product in the Caribbean–which may be considered typical of warm-weather/mass tourism destinations–has been sun,sand and sea.

Several events in the 1950s and 1960s facilitated the development of conventional mass tourism in the region. The first is the introduction of jet aircraft, which had a significant impact on the propensity for travel to the region from key generating markets, such as those in North America and Europe (Bell 1993). Second, it was during this period that many island states in the region, especially those associated with the British Commonwealth, began to move towards political independence. Such independence spawned the desire to seize a certain degree of control over internal economic development. A conscious focus on tourism meant that some island states could break away from existing colonial dependency arrangements in other economic sectors. One consequence of this, as Bell (1993: 221) noted, was the changing political structure of the region and the introduction of ‘sensitive political psyches’ that often conjured up suspicions of neo-colonialism as some economic ties to former colonial nations were not severed completely. This was especially felt through tourism (the ‘hedonistic face of neocolonialism’ (Crick 1989: 322)) because most tourists were from western countries. However, the development of tourism, through neoliberal economic packages (Telfer 2002), was still seen as an opportunity to correct this by taking control of development and management and effectively shaping the tourist; yet as Bell (1993: 220) rightly noted, tourists cannot be ‘regulated’.

The third event, which is perhaps more closely related to a broad trend, is the substantial number of migrants leaving the region at the same time as the region itself began to host increasing numbers of visitors (Pattullo 1996). Beginning in the 1950s, but continuing to the present day, many Caribbean nationals migrated (voluntarily, but occasionally out of economic necessity) to the United Kingdom, Canada, New York, Florida and California. The consequence of this has been the creation of numerous Caribbean cultural diasporas around the world. Ironically, these communities now serve as important sources of tourists, as many Caribbean expatriates living abroad frequently travel ‘home’ to visit family and friends (Duval 2002; see also Stephenson 2002).

The 1960s were characterised by Holder (1993: 21) as ‘boom years’ for tourism in the region. Growth rates of 10 per cent or more were not uncommon. Bryden (1973: 100) noted increases of over 15 per cent in the years 1961–7 for St Vincent, Grenada, St Lucia, Montserrat, Antigua and the Bahamas. For the same period, the Turks and Caicos, Cayman Islands and Virgin Islands reported a combined increase in arrivals of roughly 24 per cent. The industry management structure at the time, however, was largely in the hands of expatriates, especially large-scale hotel properties. As Sutty (1998) notes, while small-scale hotels and restaurants, largely locally owned and operated, have existed since the early beginnings of tourism in the region, their numbers have always been proportionately small. Moreover, the success of tourism during this period was largely confined to those countries that featured stronger overall economies (e.g. Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Barbados) (Prime 1976).

According to Bell (1993: 221), by the 1970s tourism began to command ‘a measure of respect...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Trends in Caribbean tourism

- Part II: Tourism development in the Caribbean

- Part III: Future prospects