![]()

Chapter 1

The Core Concepts

OPPOSITIONAL OR RELATED TERMS?

This chapter examines six basic terms. Three of them—adult, education and training—form the title of this book. The other three—learning, teaching and development—are closely related. Together, these six terms can be seen as providing the baseline of core concepts that define, in complementary and competing ways, the breadth and nature of the field of study. The final section of the chapter looks at what has been one of the key debates in this field over many years, that between liberal and vocational emphases on education and training. Chapters 2 to 7 then analyse an extensive range of qualifying concepts (for an explanation of the distinction between ‘core’ and ‘qualifying’ concepts, see the Introduction), which are widely used in association with the core concepts to signify narrower areas of interest.

As core concepts, the six terms examined in this chapter have naturally been widely discussed. Such discussion is commonly organized in terms of oppositions or dichotomies, or of inclusion and exclusion. Thus, education and training may be seen as opposing terms, the former broad, knowledge-based and general, the latter narrow, skill-based and specific (see also the discussion of knowledge and skill in Chapter 6). Indeed, this kind of approach is another representation of the liberal versus vocational debate reviewed in the final section of this chapter. Similarly, learning may be seen in opposition to teaching, the one receptive and perhaps passive (but see the examination of self-directed learning in Chapter 5), the other directive and organizational.

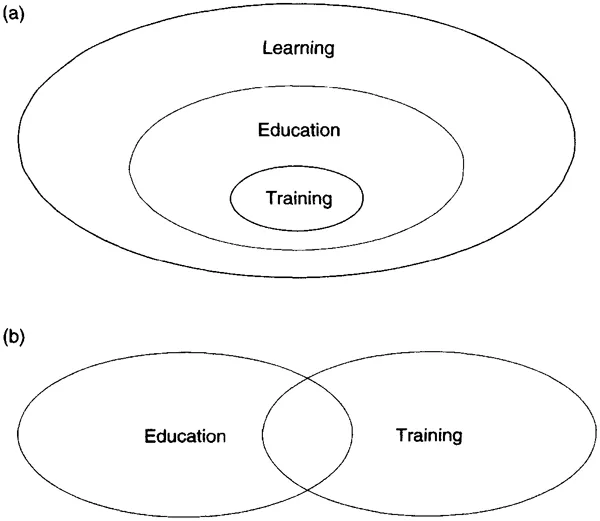

Analyses based on the idea of inclusion or exclusion quite often make use of diagrams, with the concepts discussed portrayed as circles or ovals. In such cases, training may be represented as a small oval wholly contained within a larger oval labelled education, which itself is completely enclosed within an even larger oval circle learning. Or, combining the idea of opposition with that of inclusion/exclusion, education and training may be shown as overlapping ovals (see Figure 1.1). This presentation illustrates the idea that, while some learning activities may definitively be termed either education or training, in between there is a larger or smaller group of activities which might legitimately be called either or both.

While such presentations may be criticized as inevitably rather simplistic, they do, nevertheless, demonstrate differing but widely held views or perceptions. This chapter aims to go a little deeper.

Figure 1.1 Alternative diagrammatic representations of core conceptual relations

ADULT

What do we mean when we call someone an adult? What distinguishes adult education, adult training and adult learning from education, training and learning in a more general sense? The second of these questions has an institutional or organizational context, and is discussed further in Chapter 3 (see the section on adult and continuing, p. 62). The former question will be addressed in this section.

A wide range of concepts is involved when we use the term ‘adult’. The word can refer to a stage in the life cycle of the individual; he or she is first a child, then a youth, then an adult. It can refer to status, an acceptance by society that the person concerned has completed his or her novitiate and is now incorporated fully into the community. It can refer to a social sub-set: adults as distinct from children. Or it can include a set of ideals and values: adulthood.

(Rogers 1996, p. 34, original emphasis)

At its simplest, adulthood may be defined purely in terms of age. Thus, in England, people may be assumed to become adult at 18 years old, when they get the right to vote. Until relatively recently, however, the voting age was 21 years, and there are many adult roles—for example, those requiring a specialist education or training—which cannot be entered into until this age or later. Similarly, some aspects of adulthood may be exercised before reaching 18 years old, such as marriage, full-time employment (including in the armed forces) and taxation.

Yet adult status is not accorded to all at these ages. Thus, those with severe disabilities may never achieve or be allowed full adult status. The age of majority also varies somewhat from country to country, or even within countries. And, whereas in industrialized countries the age of majority is legally defined, in developing countries it may be more a case of local cultural tradition. In such cases, maturity may be recognized in an essentially physical or biological sense, related to the onset or ending of puberty, and may vary in terms of age, not just for boys and girls but for individuals as well.

It would, of course, be naïve to believe that merely surviving long enough to wake up on one's eighteenth birthday, or passing through puberty, automatically changes one from being a child to being an adult. While the effects of puberty are externally recognizable, we do not (yet) wear barcodes on our sides recording our age, and other peoples’ reactions to us depend, in any case, upon many factors other than our absolute age. These include, most notably, our sex and ethnicity, and the reaction will vary with the characteristics of the perceiver as well as our own.

Within industrialized countries, as Rogers (1996) indicates, we also commonly recognize an intermediary stage between childhood and adulthood. Then we may be called variously adolescents, youths or teenagers. So the transition from child to adult is not sudden or instantaneous.

The idea of ‘adult’ is not, therefore, directly connected to age, but is related to what generally happens as we grow older. That is, we achieve physical maturity, become capable of providing for ourselves, move away (at least in most western societies) from our parents, have children of our own, and exercise a much greater role in the making of our own choices. This then affects not just how we see ourselves, but how others see us as well. In other words, we may see the difference between being and not being an adult as chiefly being about status and self-image.

Adulthood may thus be considered as a state of being that both accords rights to individuals and simultaneously confers duties or responsibilities upon them. We might then define adulthood as: ‘an ethical status resting on the presumption of various moral and personal qualities’ (Paterson 1979, p. 31). Having said that, however, we also have to recognize what a heterogeneous group of people adults are. It is this amorphous group which forms the customer base or audience for adult education and training.

EDUCATION

As adults, all of us have had a considerable experience of education, though this experience may have been largely confined to our childhood, and may not be continuing. The nature of education may, therefore, seem to be relatively clear to us, with particular associations with educational institutions such as schools, colleges and universities.

Such a conceptualization—that is, that education is what takes place in educational institutions—is, however, not satisfactory for three main reasons. First, it is circular, defining each concept (‘education’, ‘educational institution’) in terms of the other. Second, it tells us nothing about the qualities of education other than its location (e.g. we might just as well define oranges as ‘things that grow on orange trees’). Third, with a little thought we would probably recognize that education takes place in other kinds of institutions as well.

This final point is at the heart of the distinction between formal and non-formal education (see Chapter 3). The former is defined as taking place in educational institutions, and the latter in other kinds of institutions, the primary function of which is not education (e.g. churches, factories, health centres, prisons, military bases). It might also be pointed out that education may take place outside institutions altogether, as in the case of distance education (see the section on distance in Chapter 5), though here the association with an institution remains important.

The nature of education has been the subject of a considerable amount of analysis by philosophers of education (e.g. Barrow and White 1993, Hirst and Peters 1970, Peters 1967). Thus, Peters, in one of his more accessible works, identified three criteria for education:

(i) that ‘education’ implies the transmission of what is worthwhile to those who become committed to it;

(ii) that ‘education’ must involve knowledge and understanding and some kind of cognitive perspective, which are not inert;

(iii) that ‘education’ at least rules out some procedures of transmission, on the grounds that they lack wittingness and voluntariness on the part of the learner.

(Peters 1966, p. 45)

We can critically pick away at this quotation with relative ease. Who decides what is worthwhile, for example: the learner?, the teacher?, the institution?, employers?, the state? How much time must we allow to pass in order to detect commitment? How active (i.e. not inert) do we have to be to be judged as involved in an educational activity? In what sense can children—as distinct from adults, for whom we might at least assume some degree of voluntariness if they are participating in education—be said to be voluntarily engaged in education? Yet these points confirm how useful accounts Hike that of Peters can be in identifying and delimiting many of the key questions we need to address in order to satisfactorily define a concept like education.

A rather simpler definition has been given by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). They view education as ‘organized and sustained instruction designed to communicate a combination of knowledge, skills and understanding valuable for all the activities of life’ (quoted in Jarvis 1990, p. 105). The key phrase here, which is not explicit in Peters’ formulation, and which may be used to distinguish education from learning, appears to be ‘organized and sustained instruction’. This implies the involvement of an educator of some kind, and probably also an institution, though the education might be mediated through the printed text or computer software. It also suggests that education is not a speedy process, but takes a lengthy, though perhaps not continuous, period of time. Learning, by contrast, could be seen as not necessarily involving instruction, and as often occurring over a shorter timeframe and in smaller chunks.

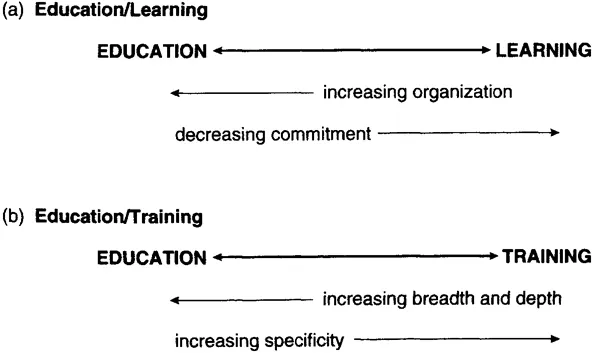

Clearly, distinctions of this kind are not always cut and dried. They allow us to conceive of education and learning as ends of a spectrum, and as shading into each other (see Figure 1.2a). Consequently, there will be instances that could be described quite legitimately as either education or learning or both. To some extent, therefore, the terms may be used interchangeably.

Figure 1.2 The education/learning and education/training spectra

How, then, to distinguish education from training? The distinction may be seen as somewhat analogous to that between education and learning, in the sense of delimiting another dimension to the area of study. The commonest approaches to making this distinction are to use the ideas of breadth and/or depth, or, conversely, to emphasize the lack of immediate application and criticality of education:

Probably the clearest if not the only criterion of educational value… is that the learning in question contributes to the development of knowledge and understanding, in both breadth and depth.

(Dearden 1984, p. 90)

we need some conception of education as independent of immediate practical considerations—one that incorporates the ability to largely, or partly anyway, transcend the working context if necessary, and which enables people to look critically at the performance of a task or role within terms of reference not provided for them only by others, but in the light of more general and perhaps universal standards.

(McKenzie 1995, p. 41)

These quotations, like the one from UNESCO, identify education as being a general rather than a specific activity. Similarly, like both the Peters and UNESCO quotations, they portray education as having to do with the development of knowledge and understanding. The latter, in particular, may be argued as being at the heart of what we mean by education:

Use of the word ‘understanding’, as opposed to ‘knowledge’, implies that what is at issue is something more than mere information and the ability to relay or act in accordance with formulae, prescriptions and instructions (the latter is characteristic of training rather than education). An ability to recite dates, answer general knowledge quizzes, or reproduce even quite complex pieces of reasoning, is not necessary to being educated. Rather one requires of an educated person that he [sic] should have internalised information, explanation, and reasoning, and made sense of it. He should understand the principles behind the specifics that he encounters; he sets particulars in a wider frame of theoretical u...