eBook - ePub

Really Raising Standards

Cognitive intervention and academic achievement

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Really Raising Standards

Cognitive intervention and academic achievement

About this book

Written by experienced teachers and educational researchers Phillip Adey and Michael Shayer, Really Raising Standards analyses attempts to teach children to think more effectively and efficiently. Their practical advice on how to improve children's performance by the application of the findings of the CASE research project will radically alter the approach of many professional teachers and student teachers as to the education of children in schools. An important contribution to the application of psychological theory in education.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Really Raising Standards by Philip Adey,Dr Michael Shayer,MICHAEL Shayer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Learning, development, and intervention

STANDARDS AND INTERVENTION

Concern with academic standards in schools and colleges has been growing since the end of the Second World War but took on an added urgency after widespread liberalisation of education in the 1960s. As universities in the United States expanded their intake from 1945 onwards professors found that many of their freshman students lacked the intellectual capacity to cope with the courses as then structured. In Britain the Butler Act of 1945 created a three-tier secondary school system of grammar schools for the top 20 per cent in intellectual ability, technical schools for those supposedly gifted in this direction, and secondary modern schools for the rest. Parallel to this state system were the private schools, highly selective in their own way. This system effectively insulated decision makers – themselves exclusively from grammar or private schools – from contact with the intellectual norms of the majority so that when comprehensive schools were introduced in the 1960s and the insulation removed, the writing classes misinterpreted their new experience as a lowering of standards rather than as the revelation of reality. Meanwhile many Third World countries were engaged in massive expansion of their educational systems, aiming for universal primary education and for increased access to secondary education. Again, mean academic performances inevitably fell as those who had previously been excluded from the educational process were exposed to curricula designed for an intellectual élite.

This dawning of realisation of the very wide range of intellectual ability within a population was slow and remained largely a topic of debate within educational circles and parental dinner tables until the lean mean monetarist era of the 1980s when the new business-oriented free marketeers saw in the issue of ‘standards’ another stick with which a coterie of professionals, in this case education professionals, could be beaten.

There are different planes upon which the educated may address the question of educational standards. There is the philosophical questioning of the meaning of ‘standards’ and whether setting standards can possibly be the same as raising them; there is the social-ethical plane of discussion of the nature of a just society and rights to education; there is the economic plane of the needs of the body economic for people of different levels and types of education; and finally there is the technical-psychological plane of describing and measuring intellectual diversity and investigating ways of improving performance generally and in particular subject domains. It is quite specifically the last of these planes upon which this book will ride and our aim is to offer a review of the relevant research and some new evidence which will provide an account of possibilities available to policy formers working on the other planes.

In particular the idea of educational intervention will be introduced and contrasted to instruction. The meaning of instruction is unproblematical: it is the provision of knowledge and understanding through appropriate activities. Instruction can be categorised by topic and by domain, and the end product of instruction can be specified in terms of learning objectives. Generally, its effectiveness can be evaluated by finding out whether or not these objectives have been attained. Effective instruction and its evaluation is the subject of many books on pedagogical methods.

Intervention is not such a familiar term amongst educators. We use it to indicate intervention in the process of cognitive development as in manipulating experiences specifically aimed at maximising developmental potential. Both instruction and intervention are necessary to an effective educational system, but we will claim that while intervention has been sadly neglected it actually offers the only route for the further substantial raising of standards in an educational world which has spent the last 40 years concentrating on improved instructional methods.

To explain this distinction further it will be necessary to spend a little time unpacking possible meanings of the word development, and contrasting it with meanings of the word learning.

DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING

At first sight there is not much danger of confusing the meaning of the word development with that of learning. Development carries with it the idea of unfolding, of maturation, of the inevitable. Learning on the other hand is purposeful, and may or may not happen. Looking a bit more closely, we might agree that some characteristics associated with development are unconsciousness, unidirectionality, and orientation towards natural goals. Let us consider each of these in turn and see where learning fits in, if at all.

Unconsciousness

There is a point in one’s adolescence when one simply cannot understand how a younger child cannot understand something. We ‘forget’ completely, it seems, the difficulty we ourselves had in understanding that concept only a year or two earlier. It is a characteristic of cognitive development that it is unconscious and that after a particular period of development has occurred we find it very difficult to think again as we did previously. Indeed one of the most important things that teachers in training need to re-learn is the nature of difficulties that children have in understanding. Having unconsciously developed beyond these difficulties themselves, student teachers sometimes think that their job will be largely a matter of ordering learning material in (to the teacher) a logical manner, and they fail to appreciate the nature of the difficulties encountered by children whose cognitive development has not proceeded so far. In contrast it is not difficult to imagine what it must be like not to have learned something. A university teacher (knowledgeable but untrained in teaching) is seldom impatient with students who know nothing of a new subject, but becomes exasperated with those who cannot follow his elegant exposition or line of proof.

Unidirectionality

It is usual to ascribe to development the idea that there is only one avenue down which it may proceed, although that avenue may be broad and may allow for some meandering from side to side. Tadpoles do not develop into anything but frogs and cognitive development inevitably proceeds from the simple to the more complex. The comparison of two states of development carries with it the implication that one is more advanced than the other. As senility approaches, we do not talk of continuing development but of regression, or loss, implying that the process is going into reverse or decaying.

In contrast, learning may proceed in any direction. There is an infinite number of things to learn, grouped in multiply-nested topics, fields, and domains. From a position of knowledge of a few things and ignorance of many, one may choose to set off in any direction to increase learning. Furthermore, consideration of two pieces of knowledge or understanding does not immediately imply that one is more advanced than the other. One cannot say that to understand the nature of atmospheric pressure is more or less advanced than to understand the nature of evil embodied in Iago.

Orientation towards natural goals

Kessen (1984) discusses the enslavement of developmentalists to the idea of an end-point to development, a goal to which development moves ‘steadily or erratically’. Although closely related to the idea of unidirectionality discussed above it does not follow inevitably from it. One can, after all, conceive of an endless road of continuing cognitive elaboration and increase in complexity. The present cognitive developmental state of the developmental psychologist does not necessarily represent perfection! Nevertheless, in most developmental models there is the strong implication of at least an empirical goal, a stage which seems to represent mature adulthood and beyond which no individual has been observed to operate. No such end point is imaginable in learning. However much one knows about a topic there is always more to learn. Learning end points are arbitrary, may be chosen at will, and defined by course syllabuses and examinations.

Both unidirectionality and orientation towards a natural goal (but not unconsciousness) are aspects of maturation. There are many biological contexts in which we think of development as something which happens almost inevitably, given adequate nutrition and the absence of disease. We speak of the development of a plant, the development of a mosquito from its larva, and the development of an embryo from a zygote. The word ‘learning’ could not be applied in such cases. But is the word ‘development’ in the term ‘cognitive development’ used more than metaphorically? If it is, then cognitive development is seen as closely related to the maturation of the central nervous system and the educator is left with little guidance but to ‘wait until the child is ready’. This is an abrogation of responsibility in the developmental process which is sometimes erroneously ascribed to Piaget. As discussed by Smith (1987), for Piaget the maturation process interacts with, and is probably subservient to, the process of equilibration. Equilibration is the establishment of a new developmental state as a result of interaction with the environment. An event, an observation, occurs which the child cannot assimilate into her present way of understanding. A possible result is the accommodation of that way of understanding to the new observation and this accommodation is a development of the cognitive processing system. It is development in that it is unconscious and can proceed in only one direction and it is partly under control of ontogenetic and phylogenetic release mechanisms. And yet, insofar as it requires a particular type of stimulus from the environment, it can become a learning process. As soon as one accepts that the environment plays a role in the process of cognitive development, the way is open for the environment to be manipulated by a parent or a teacher. If this counts as teaching, and we believe that it does, then the effect on the child must count as learning. It is this manipulation of the environment to maximise cognitive development, a very special sort of learning, which is being described as intervention in the developmental process.

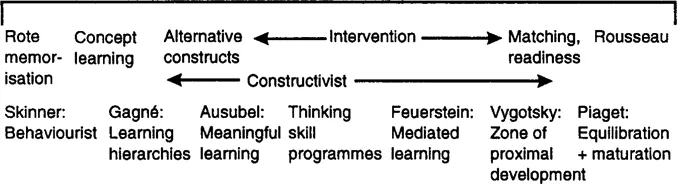

So we see, after all, that while there is a sharp distinction to be made between extreme characterisations of development and learning, they may also be seen as shading into one another along a spectrum from ‘extreme’ learning to ‘extreme’ development (Fig. 1.1). Moving from the L (Learning, Left) end of the spectrum to the D (Development, Dexter) end there is an increasing recognition of the role that development plays and a decreasing belief in the possibility of influencing development through external stimuli.

Figure 1.1 A learning–development spectrum

(Source: Tanner 1978)

At the L end of the spectrum we find rote learning in which the learner makes no connection between what is learned and knowledge already held. Whether it be nonsense syllables, learning a connection between a red triangle and a pellet of food, or learning that the formula for water is H2O without any comprehension of the meaning of the symbols, the new knowledge remains isolated and unavailable for application to new contexts. Near to this end is simple behaviourism which conceives of learning as a change in behaviour and of behavioural modification being brought about by the establishment of new response-stimulus associations. Although few would now accept that human learning can be satisfactorily described in such simple terms, behaviourism can provide guidance for the design of effective instructional methods such as the logical ordering of material, its provision in small steps, frequent recapitulation and repeated testing to ensure mastery. Such methods are appropriate for some types of learning – stereotypically the learning of multiplication tables, foreign vocabulary, or the manipulative skills required to dismantle and reconstruct a rifle. It will be noted that none of these require comprehension.

Moving to the right along the L–D spectrum we come to views of learning which give rise to more sophisticated instructional strategies:

• When new learning can be connected with something already known, we start to incorporate the beginnings of understanding into the learning process. At this point will be found Gagné’s (1965) learning hierarchies where the development of each concept is seen to demand the pre-establishment of subordinate concepts or skills.

• Plugging new learning into a network of existing concepts is one of the requirements of meaningful learning (Ausubel 1968). Arising from this is the method of investigating children’s current conceptualisations so that new material may be made meaningful by being related to existing understandings. In contrast with the behaviourist approaches there is now some consideration of learners as individuals, rather than simple focusing on the material to be learned. We will have more to say about this approach in Chapter 7.

In the terms of the instruction-intervention distinction, instruction is the most important process taking place towards the left of the L–D spectrum – that end concerned with learning and with domain specific knowledge and understanding.

At the other end of the spectrum, perhaps Rousseau (1762) should be offered the pole position with his belief that Emile should be educated by allowing his natural curiosity to open the world to him with minimum guidance by a mentor – an extreme form of leaving it all to development, or non-intervention. Some interpretations – we would say misinterpretations – of the Piagetian position on cognitive development are not far from this non-interventionist stance and since this will be an important theme throughout the book we should now devote some time to exploring this position further.

ON COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

Central to the position of cognitive developmentalists is a belief in some kind of general processing mechanism of the mind which controls all comprehension. All intellectual activity, in whatever subject domain, is monitored by this general processor. Furthermore, as the term ‘cognitive development’ implies, it is supposed that the effectiveness and power of the general processor develops from conception to maturity under the influence of genetic programming, maturation, and experience. Since neither genes nor maturation are readily amenable to change by education, the relative importance of these factors to that of experience becomes a critical question for educators.

An elaboration of the developmentalist’s position which may, but does not necessarily, follow from the notion of a developing central processor is the idea of distinct stages of development. One could conceive of a cognitive data-processing mechanism which develops by the accretion of more neural connections such that its power increased but without the quality of its processing capability changing over the 15- to 20-year period of its maturation. This would be analogous to an electric motor growing from the 5W toy which can propel a model car to a 3000 kW motor which drives a high speed train. A property of such a model of cognitive development would be that, in principle, any intellectual problem could be solved by a child of any age. The only difference between the abilities of younger and older children would be the rate at which they could deal with the elements of the problem. It is because such a consequence seems to fly in the face of experience about what children of different ages can do, however much time they are given, that most cognitive developmentalists favour a stage-wise developmental process in which at certain ages there is a qualitative shift in the kind of problems that the mind can handle. This was the nature of the theory established by Jean Piaget through 60 years of work with children and reflection on their responses.

There are interpretations of the cognitive-developmentalist position which fall into a deterministic trap: ‘Charlie can think only at the level of early concrete operations, so don’t waste your time and his by trying to teach him abstract ideas.’ This approach represents the crude ‘matching’ idea, that learning material should be tailored to make cognitive demands which are no higher than the current level of thinking of the learner. Many educators are, quite reasonably, shocked by such a negative view of the teaching and learning process which concentrates more on what children cannot do than on what they can do and views intelligence as a potential with which a child was born and about which nothing can be done by the parent or educator. It may be this sort of interpretation (of which we ourselves have been accused – Shayer and Adey 1981, White 1988) which accounts for the demise in respect accorded to Piaget as a guide for educators. An alternative approach to a model of stage-wise cognitive development whose rate is determined by the interaction of genetic, maturational, and experiential factors is to ask what is the nature of experiences which can be provided which will maximise the potential set by factors over which we have no control? In the pages which follow we propose to show that the strategy of matching the intellectual demand of the curriculum to the current stage of development of the learner is severely flawed. A deliberate policy of challenging learners to transcend their present level of thinking not only accelerates their rate of intellectual development, but also in the long term brings about the achievement which a matching policy on its own would have denied them.

SOME APPROACHES TO INTERVENTION

Following the realisation of the ‘true’ range of ability of the population mentioned at the beginning of this chapter the practice, if not the idea, of intervention gradually came out of obscurity during the 1970s to address a variety of populations and age groups. In contrast to the crude matching of material to supposed cognitive level of the learner, programmes which focus on intervention turn attention to the educational environmental factors which may maximally affect the developmental process and so drive on the elaboration of the general cognitive processor. Such programmes and theories will be found in the centre-right region of the L–D spectrum, to the right of theories of instruction which concentrate on the effective presentation of material wit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- 1. Learning, development, and intervention

- 2. Describing and measuring cognitive development

- 3. A review of intervention programmes

- 4. Features of successful intervention

- 5. Case: The development and delivery of a programme

- 6. Evaluating the programme

- 7. Implications for models of the mind

- 8. Other domains, other ages

- 9. Changing practice

- 10. Really raising standards

- Appendix

- References

- Name index

- Subject index