eBook - ePub

From Mycenae to Constantinople

The Evolution of the Ancient City

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Mycenae to Constantinople

The Evolution of the Ancient City

About this book

Tomlinson presents studies of selected ancient cities, ranging from the earliest development of urban architecture in Europe to the imperial cities of Rome and Constantinople. It gives an account of their architecture, not merely from the art historical point of view, but as an expression of the social organisation, and political systems employed by the people who lived in them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Mycenae to Constantinople by Richard A Tomlinson,Richard A. Tomlinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION: CITIES AND THEIR CREATORS

In this book are discussed the form, layout, and buildings of thirteen places in the Greek and Roman world, all of which had the status of cities. They vary considerably, and no simple definition embraces them all. They differ in their political systems, their economies, their size, their history. One of the oldest of them, Mycenae, is also the smallest, but this is a coincidence. Most of them are successful, if success is to be judged by their longevity. Athens can trace its origins to the second millennium BC at least, and has existed as a city ever since, while Thessalonike has flourished as a major city without a break since its foundation in 316 BC. All of them, at one time or another, are particularly important, though that importance may fade with changing circumstances. It is these that determine the city’s fate, that bring it into existence, encourage its development, and then allow it either to continue or to fade away. More specifically, my cities are dominated by the classical concept of the Greek city-state, even if not Greek. For the Greeks, the city—the polis—was not merely a natural way of life, but the only acceptable one for normal human beings. Aristotle’s definition of man as a political animal meant exactly this: man is by nature destined to live in cities.1 Politics form the art of living in cities, and citizenship is the right—and privilege—of those who form the community. Translate them into Latin, as cives, and their form of life is the basis of civilisation. All this reflects the historical realities: that is, in the conditions of the Mediterranean world in the first millennium BC and after, it is the normal thing for the human population to form communities, rather than live in isolation, and these communities are the essential basis for those advances which constitute the achievements of civilisation.

Aristotle, of course, went much further in his definition of the polis and political systems. He appreciated the different forms that existed, and on the basis, we are told, of a study of their constitutions and constitutional history, made the analysis of the various forms in his treatise on Politics. Even confining himself to the Greek world Aristotle found 150 different constitutions for which written studies were prepared (only one—Carthage—was not Greek). All these studies have been lost, with the exception of the most important of them, Athens, rediscovered on a papyrus found in Egypt in the late nineteenth century. That this is demonstrably not all Aristotle’s own work does not alter its significance. This variety is only extended by the cities of the Roman world, and the changes introduced after Aristotle’s time.

Thus differences are to be expected. At the same time, there are common factors behind the growth of the city system. The concept of the community is fundamental. It is essential for economic co-operation and for defence. Greek cities had their place names, Athens, Thessalonike, and so forth, and on the analogy of modern usage it is normal to refer to them by these names, but this was not the practice of antiquity. Then it was the community rather than the place which was paramount, so the ancient historians tell us about the Athenians, rather than Athens. The nature of the city thus depended on the nature of the community, and this included more than the living inhabitants. It also embraced the gods, who in their anthropomorphic nature were vividly present, and whose needs and requirements were of supreme importance. It included the ancestors, who were a very real part of the continuing families, whose very continuity was the whole nature of the community, whose burial places required respect.2

My cities, then, are places where these communities existed: their variations are the variations from community to community, and in the fortunes that befell them. Aristotle, and others, speculated about their ideal form: the reality, the differences between them, shows that there was no single ideal, and that they varied in response to the conditions that affected them. All are the results of the accidents of history as well as the fundamentals which they all share. The basic form is the small agricultural community, self-contained and with sufficient land to produce the necessities of life. Its inhabitants work the fields that surround it, returning to the houses grouped together to form the settlement which is the basis of their community life. Unless external factors are involved, such communities remain small. There is a practical limit to the area of land that can be farmed conveniently from a single centre, if the farmers reside in that centre rather than in isolated farmsteads. The farmers have to travel from the settlement to their fields, and if this distance involves more than an hour or so’s journey, then time and energy are lost. It is more practical, therefore, to have a network of small communities, and provided they can live at peace with each other, and are not subject to external enemies, this constitutes a natural pattern. In favoured circumstances, such communities can continue unchanged not just for centuries but for millennia; their mud-brick houses collapse and are replaced, collapse and are replaced again, so that the settlement takes the form of a mound, increasing in height as generation succeeds generation. Such places exist in northern Greece: they are particularly noticeable in the broad plains of central Thrace, where the mound of Kara Novo has been excavated to show the succession of generations over millennia.

Such (apparently) idyllic and undisturbed conditions are rare, and the ancient world of the first millennium BC and later is not merely a collection of small, peaceful villages. The breakdown of such simple systems can be attributed to greed, the desire to control greater sources of wealth than those available to the simple village communities: indeed, one of the reasons for the unchanging existence of these communities in central Thrace is material poverty, the lack of goods which make aggrandisement desirable. The Classical communities, on the other hand, thrive in proximity to the sea, for it is seaborne trade which gives them access to material luxuries greater than they can produce for themselves. This, in turn, sets a higher value on the products of the land than was necessary for survival, so that the successful and aggressive seek to extend their boundaries and the region under their control, and, at the same time, to protect their own possessions against the depredations of others. None of the places described in this book could have assumed the form they took if they had been isolated from external influences; for the simple places, Kara Novo typifies them all, and there is little call for individual descriptions.

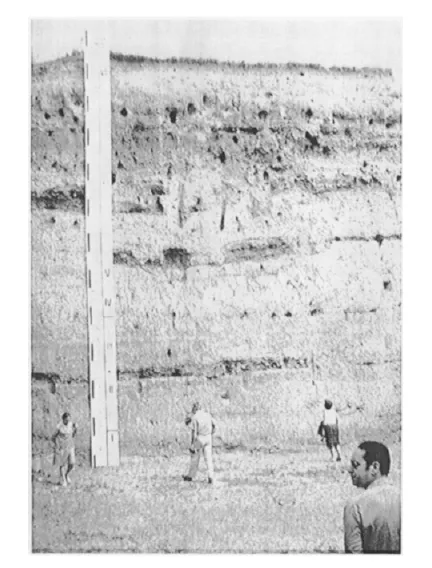

Figure 1.1 Section through the mound of Kara Novo, Bulgaria. The ‘rule’ marks (in Roman numerals) the different levels as settlements decayed and were replaced.

All of them are thus affected by the wider conditions of the world in which they exist, and the historical changes which determine those conditions. Crucial here is the extent to which they could maintain their own independence within the wider world to which they belonged. Thus the general pattern of ancient history, and the changes in its circumstances, affect the existence of the cities. Since many of them survive through very different circumstances, some general outline is desirable, to which their individual history can be related.

Several of our cities traced their origin to the times which we regard as prehistoric, to the later Bronze Age of the second millennium BC (or even earlier, though this becomes more difficult to evaluate). By definition, there is no surviving history for this, though the Greeks of the historical period believed they knew their earlier history. For us this means the poems attributed to Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey, though it must be remembered that in the Classical period many more such poems survived, some of them with traditions limited to particular parts of Greece. The interpretation of the evidence that survives from these is fraught with difficulty, and for these remoter times the archaeological evidence seems a sounder basis for understanding. This is not the place to discuss the argument that arises about the interpretation: what is clear from the nature of cities like Mycenae is that they flourished on external wealth, whether this was acquired by plunder or trade, and that they existed in a time of increasing insecurity, which led them to build, and strengthen and strengthen again the massive fortifications which defended them. Mycenae, then, is typical of the more important and successful places of its own time, but it was preceded by other places, the cities of Crete, which are different in form and assuredly different in their political and economic circumstances, though it is unproductive to reconstruct what these were.

Equally, the conditions of the late Bronze Age which underlie the success of Mycenae at that time themselves give way to the profoundly changed circumstances of the next phase in Aegean history, the Dark Age, which begins at the transition from the second to the first millennium BC. This is a time which is not conducive to city development in that region. There are signs of migration and depopulation, followed by movements of people within Greece itself. More important is a marked decline in overseas contacts, and consequently in accessible wealth, with the result that the communities lapsed rather into the isolated village form. If we were concerned with the Aegean world alone, this would have to be regarded as the new normal state, but it is important to remember that this disintegration and isolation did not affect the cities of the Levant, or the people of Egypt, except in a very marginal way, and that there the patterns of earlier civilisation continued. Another difficulty is in assessing the absolute extent of the turmoil and decline in the Aegean world. Two of our places—Mycenae and Athens—certainly flourished in the late Bronze Age, as their archaeology attests, and continued to exist through the Dark Age, re-emerging again at the beginning of recorded history as places with a continuous history. Mycenae was still defended by its massive Bronze Age fortifications, as was the Acropolis at Athens, and the historical Athenians certainly believed they were descended from the earlier inhabitants. Continuity cannot really be attested in the archaeological record, and is denied by many. If we believe what the Greeks themselves believed of themselves, then we must accept for some places at least a real continuity: equally, for others discontinuity is a more likely fact. Even so, all were equally isolated, and so undeveloped, though the difference of tradition may well explain (or at least underlie) differences of form.

The next phase, which saw the end of the Dark Age, is crucial to the development of the Classical city, and this has been much discussed, analysed and theorised about.3 Sometimes the theory (or ‘model’) seems to take charge: a possible explanation is worked out, and the rise of the different cities explained accordingly. The probability is likely to be more complex. Certain factors can be seen to be operating, but their effect is varied, depending on things such as geography, or the nature and origins of the population, where existing variables are clear. The places described here differ from each other, and none can be regarded as entirely typical. All the same, they all develop within the same general circumstances, and these are worth considering, even in a simplified form. The crucial factor is the change from a world of isolation to one which was once more involved in significant overseas contacts: by deduction, from a self-contained, self-sufficient economy to one where the resources available to the community now needed to be exploited in the pursuit of overseas wealth. There is no doubt that such a picture, though true enough as a starting point, is oversimplified. The Greek world did not lose all overseas contacts in the Dark Age: not all the emerging more complex states of the Classical world were themselves directly involved in overseas trade. Nor should we look to trade rivalries. Some places—such as Corinth—were particularly well placed for the conduct of trade, and profited accordingly. Others did not trade themselves, but certainly wanted the goods and materials the traders could now provide, and therefore also needed to develop their systems to take advantage of what was available. Thus the histories of Athens, Sparta and Corinth in the eighth and seventh centuries BC all depend on the changing conditions of the Aegean world at the time: but the exact form of their involvement in them was very varied. All three were acknowledged by the Greeks themselves as poleis, as city-states in the sense that Aristotle analysed the cities, but he and the rest of the Greek world were equally aware of the differences that marked them off from each other. The argument can be extended to other places not discussed in this book, such as Miletus in Ionia, or Syracuse in Sicily, to quote examples at the limits of the Greek area.

What links them all is the new scale and size of the state. Their political control extends over much greater areas. Communities which were previously living in independent isolation are now subsumed into the larger political unit: the city becomes, in effect, a territory with more centralised control. How that control was exercised—and so the nature of the city—was the principal variant. At Sparta, notoriously, the outlying peoples taken into the state might find themselves reduced to the status of serfs—helots—tied to the land as the property of the community (not the individual citizen), bound to work the land for the benefit of the privileged class to whom the land had been allotted. At Athens this was not so, and though the condition of the mass of the population was at times a matter for dispute, the extension of the rights of full citizenship to all free inhabitants of Athenian territory became accepted. Athens and Sparta and Corinth have it in common that they are centralised states, where the urban centre is also the proper place for the exercise of political life (even though the political system itself varied). Yet the physical nature and appearance of their urban centres was equally varied, and the paradox is that the one which was politically and economically most centralised—Sparta—was in physical and architectural terms the least resplendent of them, while of course the one which adorned its urban centre with the most splendid buildings—Athens—was, at the time this happened, politically the most decentralised. It is a valuable warning.

Of course, there are unifying factors, whose existence is a necessary precondition of the city form. From whatever sources—and dependents and subordinates—they drew their wealth, they themselves must be independent and free, self-governing, and following their own laws without control or interference from any other state. Size is immaterial: independence is all. Thus the Classical city-state was in essence the creation of a brief moment in the changing pattern of history, a time when isolation had broken down, but when the still-fragmented states were not themselves threatened by greater, external powers. The next crucial change is the rise of the Persian Empire, territorially enormous and with resources to match, under the autocratic control of a king who called himself the Great King, King of Kings. The existence of such states was a general condition of life in the Near East, and the Greeks were already involved with them, at least to the extent to which they controlled (or not, depending on circumstances) the Near Eastern communities in Syria and Phoenicia, with which the Greeks traded. Where conditions and political circumstances varied (particularly in Egypt) the nature of Greek economic involvement also differed. Again, we should avoid the danger of overgeneralisation. This apart, it is likely that the Greeks did not overmuch concern themselves with the nature of Near Eastern politics. All benefited from trade, and this was all the Greeks who came to the Near East needed.

The change came about with the creation by the Persian king Cyrus, in the middle of the sixth century BC, of the most successful, in terms of extent, of the Eastern empires. By historical accident, rather than design, this impinged much more on the fortunes of the Greeks. Cyrus overran the whole of Asia Minor and so, on the western fringes of his Empire, he became the master of those Greek cities formerly dominated by his defeated enemy, Croesus, King of Lydia. In time, this developed into the threat that the Persian Empire would incorporate all the Greek cities, by conquest: the crisis came with King Xerxes’ invasion of Greece in 480 BC, which was defeated, partly by fortuitous circumstances but more conspicuously by the ability of the independent Greek cities to form an alliance and pool their resources. If they had tried to remain independent of each other, and self-sufficient, the Persians would have picked them off one by one. This in fact, though guaranteeing the freedom of the Greeks, meant-the eventual end of the Classical city ideal. To counteract the Empire, the Greeks had to form larger political units, the system of alliances dominated by Sparta and Athens which the latter certainly exploited to her own economic advantage. The reluctance of other Greeks to accept this meant that it was merely a temporary phase; more lasting was the desire of the Greeks themselves to replace the Persians as the masters of the known world, and significantly this needed the substitution of an effective monarchy, that of Philip and Alexander, kings of Macedon, for the ineffective disunity of the Greek cities.

Philip was a clever diplomat, who realised the necessity of reconciling the Greek cities which he had defeated and, in effect, subjugated to the reality of his monarchical authority without trampling too harshly on their traditional desire for autonomy. In Macedon itself cities existed frankly as elements of the kingdom, subject to royal authority in so far as their citizens were defined as Macedonians. Such a direct system would have been offensive to the Greek cities, who were reconciled by being treated as allies rather than subjects. After Philip’s death, Alexander’s treatment of the cities was more erratic. Following their partial rebellion he had to resubdue them and to demonstrate the realities of his power by destroying the leading rebel, Thebes, razing it to the ground. Having made his point he then restored the more diplomatic approach; but even so, as by his conquests in the Near East he succeeded in substituting his authority for that of the Persian kings, he relapsed more into autocracy. In areas which had been ruled by the Persians, autocracy was the only political system which could be effective.

In such a situation, the relationship between Greek city and Macedonian king became ambiguous, and this ambiguity continued after the death of Alexander and the division of his Empire into a patchwork of separate kingdoms by the Macedonian generals who succeeded to his political and military power. The ambiguity had existed even before Alexander. Not all Greek cities were governed collectively, whether by a democratic assembly, as at Athens, or by a militarily élite citizenship, as at Sparta. Autocrats and Greek cities had coexisted from earlier times, whether the autocrat was a home-produced dictator (a tyrant, the technical Greek term for an individual who established an unconstitutional autocracy) or a foreign king who had assimilated the city into his kingdom. There is interesting evidence from Halicarnassus, a Greek city located on the coast of Caria in south-western Asia Minor, which in the fourth century became the capital of a Carian dynast, Mausolus.4 There he built his palace, and there was constructed his fabulous and spectacular tomb, the Mausoleum, which dominated the city, and was clearly intended as a focus of cult in a way which was unthinkable for any ordinary Greek. Here we have as clearly as possible the contrast between monarchy and the Greek city ideal. But in other respects, the contrast is not so clear. In Mausolus’ Caria, Halicarnassus and other cities (some of them, like Mylasa, Carian rather than Greek in origin) continued to function administratively in the pattern of Greek city-states, and there is documentary evidence, inscriptions on stone, which record dealings between the city and Mausolus as though the latter were only an ordinary citizen. It is, of course, a politeness only, but the politenesses were being observed, despite Mausolus’ autocratic power. Even the Mausoleum and its cult has a perfectly good Greek precedent in the particular respect afforded to the founder of a city: Mausolus could, with reason, be regarded as the refounder of Halicarnassus.

Cities in fact had to balance on the one hand the traditional desire for autonomy, and on the other the benefits which resulted from inclusion in the realm of a monarch. Only the most successful and prosperous cities could afford to be free from royal domination, and even these could never compete on equal terms. One of the most powerful of them, the island state of Rhodes, had to seek alliances with the Hellenistic kings, the successors of Alexander, to counteract the threats exerted by other kings who were their enemies. Nor was it only a matter of military protection; the economic benefits which could be cajoled out of a co-operative monarch, either direct gifts, or trading advantages, were well worth looking for. In practice the cities of the Hellenistic Age were more or less dependent on the kings.

What is important is that although the kings needed to dominate the cities that existed, and could elsewhere have exercised direct authority themselves in the traditional Eastern manner, nevertheless they sought to establish Greek cities within the areas of their kingdoms which previously were not Greek at all. This is a policy which can be traced back at least to Philip, and marks first of all a continuation of Macedonian policy, by which cities could be founded, but which remained subject to the king. By this means, a Macedonian city established in a non-Macedonian area (Philippopolis in Thrace, for example) becomes a means of establishing a bastion of loyalty in a potentially hostile region. Such cities had no tradition of independence or autonomy, and served their royal founders well. This policy was continued by the Seleucid dynasty who succeeded to the Asiatic parts of Alexander’s empire. The Seleucid cities of Syria, especially the chief of them, Antioch, were substantial and prosperous places, and were among the leading cities of the Hellenistic world, but they never showed any desire for independence, remaining loyal to their kings.5 When, in the passage of time, the kings and their authority dwindled so that they could not effectively offer the protection needed, the cities were frightened at the prospect of having to fend for themselves, and looked for new protectors. It was not for nothing that Antioch used the date of its foundation by Seleucus as the starting point for its chronological record, long after the Seleucid dynasty had disappeared.

In Egypt, on the other hand, where Ptolemy son of Lagos had made himself king, the city was not used in the same way. There were, in fact, only two cities: Alexandria, founded by Alexander the Great, and its counterpart, Ptolemais, founded by Ptolemy in Upper Egypt, and too remote to be anything other than a royal dependency or show-piece. Alexandria benefited from the Ptolemies, as befitted a royal city, but it was notoriously disloyal, often treating the kings with disdain; perhaps the Alexandrians could only respect their founder, Alexander himself, who was buried in the city, his corpse having been hijacked for this very purpose by Ptolemy when it was on its way to the traditional burial place of the Macedonian kings at Aegeae. At Alexandria his tomb became, like the Mauso...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: Cities and Their Creators

- 2 Buildings: Types and Functions

- 3 Mycenae: The Forerunners

- 4 Athens and Piraeus

- 5 Corinth

- 6 Priene

- 7 Alexandria

- 8 Pergamon

- 9 Thessalonike

- 10 Cyrene

- 11 Rome

- 12 Pompeii

- 13 Lepcis Magna

- 14 Palmyra

- 15 Epilogue: Constantinople

- Notes

- Select Bibliography