![]()

I

Theories

![]()

1

Toward a Dual-Systems Model of What Makes Life Worth Living

PAUL T. P. WONG

Trent University

What makes life worth living? This is probably the most important question ever asked in psychology because it is vitally related to human survival and flourishing. It is also a highly complex question with no simple answers to the extent that it touches all aspects of humanity—biological, psychological, social, and spiritual. Thus, only a holistic approach can provide a comprehensive picture of meaningful living. To further complicate matters, every person has his or her own ideas on what constitutes the good life. Many people believe that money is the answer; that is why money remains the most powerful motivator in a consumer society. Others, especially those in academia, believe that reputation matters most. For those people living in abject poverty, heaven is being free from hunger. Given such individual differences in values and beliefs, is it even possible to provide general answers based on psychological research?

Viktor Frankl (1946/1985) found a way to reconcile general principles with individual differences. On the one hand, he emphasized that it was up to each individual to define and discover meaning in life; on other hand, he devoted most of his professional life trying to uncover the principles that could facilitate individuals’ quests for meaning. His main finding is that “the will to meaning” is the key to living a worthy and fulfilling life regardless of personal preferences and circumstances (Frankl, 1946/1985; Chapter 28, this volume). The present chapter represents an extension of Frankl’s work in a more precise and empirically testable model.

Numerous psychological models have been proposed to account for meaning in life. For example, the existential perspective tends to focus on learning to live with the dark side of the human condition, such as suffering, meaninglessness, loneliness, and death, and creating meaning through one’s courageous choices and creative actions (Sartre, 1990; Yalom, 1980). In contrast, positive psychology emphasizes positive experiences and emotions as the pillars of a worthwhile life (Seligman, 2002; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). The dual-systems model provides a bridge between these two intellectual traditions and integrates various streams of research relevant to the question of the meaning of life.

The dual-systems model attempts to address three important issues vital to developing a comprehensive psychological account of a meaningful life: (a) what people really want and how to achieve their life goals, (b) what people fear and how to overcome their anxieties, and (c) how people makes sense of the predicaments and paradoxes of life. The first two issues are instrumental in nature, having to do with adaptive mechanisms, whereas the last issue is philosophical and spiritual in nature, having to do with how one makes sense of the self and one’s place in the world. Answers to the first two issues depend on one’s philosophy of life.

What Do People Really Want?

It is a truism that for life to be worth living, people need to enjoy living and feel satisfied that their needs and wants are met. Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy model posits that people need to meet all five levels of needs in order to be self-actualized. Peterson and Seligman (2004) propose that people want to live a life of pleasure, engagement, and meaning in order to live a really happy life. Baumeister (1991) emphasizes that meaning in life depends on purpose, efficacy, value, and self-worth. Based on implicit theory research, I directly asked people what they really wanted in order to live an ideal meaningful life if money were no longer an issue (Wong, 1998b). Based on numerous studies, I have found that the worthy life consisted of the following components: happiness, achievement, relationship, intimacy, religion, altruism, self-acceptance, and fair treatment. All the foregoing models implicitly assume that (a) we know that the various psychological needs are markers of the good life and (b) we know how to meet these needs.

Unfortunately, we do not live in an ideal world with perfect justice, equal opportunities, and unlimited resources for all individuals to get what they want in life. Fate often intervenes, such as earthquakes and accidents, which totally disrupt one’s life. Another relevant issue is that we are not perfect. Most people do make mistakes and often derail their own best efforts because of some such character defects as greed and blind ambition. At the end of their earthly journey, some people may discover that they have not really lived even though they were successful in realizing all their dreams and wishes. Finally, there is a philosophical dimension. People need to reflect on the big picture and learn to come to terms with such existential givens as sickness, aging, and death, which pose a constant threat to their dreams of a good life. They also need to examine their own lives to make sure they do not spend a lifetime chasing after the wind.

What Do People Want to Avoid?

We do not need empirical proof that all people naturally avoid pain, suffering, and death. Similarly, we want to be free from deprivation, discrimination, oppression, and forms of ill-treatment. We also shun rejection, opposition, defeat, failure, and all the obstacles that prevent us from realizing our dreams. We want to stay away from difficult people who upset us and make our lives miserable. Finally, we all struggle with our own limitations—areas of weaknesses and deficiencies.

In addition to the foregoing litany of woes, we also need to be concerned with the existential anxieties inherent in the human condition (Yalom, 1980). No one really enjoys suffering, but meaning in life depends on discovering the meaning of suffering (Frankl, 1946/1985). Furthermore, our ability to achieve the good life depends on our efficacy in coping with stresses, misfortunes, and negative emotions. The dual-systems model not only recognizes the inevitable unpleasant realities of life but also specifies the mechanisms of translating negativity into positive outcomes.

How Do People Make Sense of Life?

People may not be able to articulate their philosophy of life, but they all possess one; for we all have assumptions, beliefs, values, and worldviews that help us make sense of our lives. The huge literature on attribution research suggests that people are both lay scientists and philosophers (e.g., Weiner, 1975; Wong, 1991; Wong & Weiner, 1981).

Our philosophy about what constitutes the good life can determine how we make choices and how we live. Those people who believe that the good life is to eat, drink, and be merry will spend their lives on the hedonic treadmill. Those who believe that the purpose of life is to serve God will devote their lives to fulfilling God’s calling.

Every philosophy of life leads to the development of a certain mindset—a frame of reference or prism—through which we make value judgments. For example, hedonism will contribute to a happiness-mindset that values positive experiences and emotions as most important for subjective well-being. Some of the widely used instruments of life satisfaction reflect the happiness-mindset. For example, the well-known Subjective Well-Being Scale (SWBS) by Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin (1985) include such items as “My conditions of life are excellent” and “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life.”

In contrast, a eudaimonic philosophy (Aristotle, trans. 2004) is conducive to a meaning mindset that considers virtue as the key to flourishing. The joy of living comes from doing good. As a case in point, Jim Elliot died young as a missionary because he chose the path of self-sacrifice to serve God and others: “He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain what he cannot lose” (Elliot, 1989, p. 15). Mahatma Gandhi, who gave his life in the struggle for freedom for his country, wrote, “Joy lies in the fight, in the attempt, in the suffering involved, not in the victory itself” (Attenborough, 2008, p. 3). A sense of life satisfaction can come from the defiant human spirit of fighting with courage and dignity. In Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus (1942/1991) concludes that “the struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy” (p. 123). This type of life satisfaction can best be measured by a psychological instrument that focuses on eudaimonic well-being (Huta, 2009; Waterman, 2008).

Why do I focus on the meaning mindset? For most people, life is full of hardships and struggles. A life of endless happiness without pain can only be achieved by reducing human beings to robots or brains connected to machines capable of delivering constant stimulation to the brain’s pleasure center. Even when individuals are successful beyond their wildest dreams, their lives are not exempt from physical pain and psychological suffering. Moreover, a single-minded pursuit of personal happiness and success is not sustainable—eventually, it will lead to despair, disillusion, and other psychological problems (Schumaker, 2007). Thus, Schumaker advocates the creation of a society that will “attach greater value to the achievement of a meaningful life” (2007, p. 284).

The meaning mindset focuses on the person (Maslow, 1962; Rogers, 1995) as meaning-seeking and meaning-making creatures. It also capitalizes on the human capacity for reflection and awakening (Wong, 2007). The ability to reflect on and articulate one’s worldview can facilitate positive changes. The meaning mindset also involves understanding the structure, functions, and processes of meaning (Wong, in press-a, in press-b). Without a personally defined meaning and purpose, individuals would experience life as being on a ship without a rudder. An enduring passion for living comes only from commitment to a higher purpose. In short, a meaning mindset will facilitate the dual process of striving for authentic happiness and overcoming adversities.

The Basic Postulates of the Dual-Systems Model

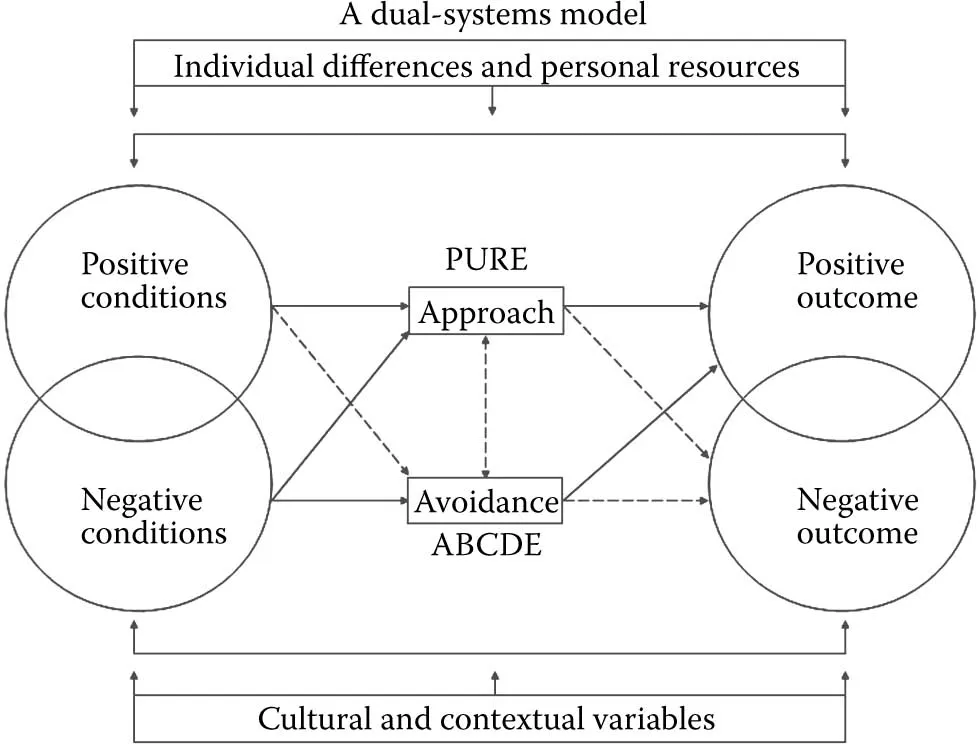

The basic tenets of logotherapy (Chapter 28, this volume) are applicable to the dual-systems model. The following postulates are specific to the dynamic interaction between positives and negatives (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Schematic of the key components and links in the dual-systems model.

1. In reality, positives and negatives often coexist. It is rare, if not impossible, to have purely positive or negative conditions (Chapters 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 21, and 22, this volume).

2. Similar to the concept of yin and yang, every positive or negative element contains a seed of its opposite. For example, one can be happy about a promotion but worried about the extra stresses involved. By the same token, one can feel sad about losing a job but feel happy that one can go back to school for retraining. Thus, a purely either–or dichotomy is inadequate in capturing the complexities of human experiences.

3. The approach and avoidance systems coexist and operate in an interdependent fashion. The approach system represents appetitive behaviors, positive affects, goal strivings, and intrinsic motivations. The avoidance system represents defensive mechanisms against noxious conditions, threats, and negative emotions. Both systems need to interact with each other in order to optimize positive outcomes (Chapters 2, 7, and 11, this volume). In other words, neither system can function effectively all by itself over the long haul. For example, an appetitive system will eventually implode unless it is checked by the warning of risks and discomforts associated with overconsumption. The approach and avoidance systems each involve different emotional-behavioral processes and neurophysiological substrates. When the two systems work together in a balanced and cooperative manner, the likelihood of survival and flourishing is greater than when the focus remains exclusively on either approach or avoidance.

4. Different systems predominate in different situations. In countries that enjoy peace and prosperity, the approach system predominates in everyday-life situations. However, in areas devastated by war or natural disaster, the avoidance system predominates. Yet no matter which system predominates, individuals are always better off when they make good use of the two complementary systems. For example, even in desperate times of coping with excruciating pain and impending death, the joy of listening to beautiful music can make life worth living.

5. When a person is not actively engaged in approach or avoidance, the default or neutral stage is regulated by the awareness regulation system. The Pavlovian orienting response (Pavlov, 1927/2003) is a good example of this effortless attention system. Mindful awareness is also important because it is primarily concerned with being fully attuned to the here and now; as a result, it makes us open to new discoveries of the small wonders and miracles of being alive.

6. Meaning plays a pivotal role in the dual-systems model. Meaning is involved in life protection as well as life expansion, thereby contributing to enhancing well-being and health and buffering against negatives (Chapters 7, 8, and 20, this volume).

7. Self-regulation systems are shaped by individual differences, personal resources, and cultural or contextual variables (Chapters 2, 7, 11, 20, 21, and 22, this volume).

A Description of the Dual-Systems Model

Individual Differences

How we make sense of the environment and respond to various situations reflect individual differences. The Big Five personality factors (McCrae & Costa, 1987) are relevant; for example, openness is related to mindful awareness, and conscientiousness is related to responsible actions. One’s mindset is relevant to making value judgments. The story one lives by can also make a difference (Chapters 5, 14, and 18, this volume). Finally, individual differences in psychological resources may affect efficacy in coping with the demands of life (Wong, 1993).

Culture and Cultural Context

Both personality and adaptation efforts are shaped by cultural contexts (Chapter 16, this volume; Wong & Wong, 2005). Cultural influence is especially strong in shaping our perception, thinking, and meaning construction (Bruner, 1990; Shweder, 1991). In fact, the complete process from antecedent conditions to outcomes ...