- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Crime, Disorder and Community Safety

About this book

This book provides an analytic overview and assessment of the changing nature of crime prevention, disorder and community safety in contemporary society. Bringing together nine original articles from leading national and international authorities on these issues, the book examines recent developments in relation to a number of specific groups - the disadvantaged, the socially excluded, youth, women and ethnic minorities. Topics covered include:

* the increase in local authority responsibility for crime control and community safety

* the development of inter-agency alliances

* the changing nature of policing * the passing of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Identity, community and social exclusion

Introduction

For the majority of social commentators, community safety programmes to control crime and anti-social behaviour are an exercise in the obvious. ‘Community’ is a wholesome, homogeneous entity waiting to be mobilised, ‘safety’ is a risk free end state – the self-evident goal of public desire – whilst ‘crime’ and ‘anti-social behaviour’ are entities which are readily recognisable by any decent citizen. Indeed, the trio – community, safety and crime – become elided together, each term defining each other. Thus the intense, socially rich interacting community is seen to be the very antithesis of crime and is indeed the place and source of all safety.

Nowadays, as Adam Crawford puts it, ‘the attraction of the notion of “community” unites and transcends the established ... political parties’ (1997: 45). He goes on to write that ‘community ... is cleansed of any negative or criminogenic connotations and endowed with a simplistic and naïve purity and virtue’ (ibid.: 153). Thus problems of crime and disorder are ascribed to a malaise of community and their solution is seen as the regeneration of community. Such a perspective can readily be seen as an aspect of modernity, in particular the social engineering characteristic of the post-war period. This was a period wherein slums were cleared, towns were planned and ‘rational’ communities were constructed – the apotheosis being the ‘new town’ developments, the more mundane and commonplace being the modernist tower blocks interspersed with family maisonettes and bleak gardens characteristic of the post-war city.

It has been the role of critical criminology to stand outside such conventional wisdoms and to problematise each of these seeming certainties. Community becomes seen as a reality lacking coherence, a rhetoric invoked to ensure the domination of one group over another, a key instrument of social exclusion. Safety becomes a curtain for fear, the miscalculation of risks, the denial of excitement and the excuse for xenophobia towards outgroups. Finally, crime and anti-social behaviour are social constructs which are bestowed by the powerful on disapproved behaviour but with no essential reality or core. In fact, their definitions are frequently contested within localities and adherence to criminal values can even be a dominant aspect of community.1

My concern in this chapter is not to reiterate these doubts but rather to point to the fashion by which the massive changes which have occurred in the last third of the twentieth century, in the basic building blocks of society – employment, the family and community itself – have transformed and magnified such doubts. For the shift from the modernity of the post-war period with its high (male) employment, intense communities and stable families, to the conditions of late modernity has been associated with a remarkable problemati-sation of each area.

The coordinates of order: class and identity in the late twentieth century

First, before mapping the terrain of late modernity, I wish to briefly establish coordinates. Nancy Fraser, in her influential Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the Post-Socialist Condition (1997), outlines two types of politics: those centring around distributive justice and those centring around the justice of recognition – that is class politics and identity politics.2 She points to the rise in prominence of the latter – a phenomenon which I will attempt to explain later in this chapter. However, what concerns me here is to develop and explain this distinction as a basis for an analysis of social order and political legitimacy. In my book The Exclusive Society (1999), I point to the two fundamental problems in a liberal democracy. First is the need to distribute rewards fairly so as to encourage commitment to work within the division of labour. Second is the need to encourage respect between individuals and groups so that the selfseeking individualism characteristic of a competitive society does not lead to a situation of war of all against all. Individuals must experience their rewards as fair and just and they must feel valued and respected.

I now wish to develop this distinction between the sphere of distribution and that of recognition. Central to distributive justice is the notion of fairness of reward, and in modern capitalist societies this entails a meritocracy in which merit is matched to reward. Recognition involves the notion of respect and status allocated to all, but if we stretch the concept a little further, it also involves the notion of the level of esteem or social status being allocated justly. Indeed, both the discourses of distributive justice and recognition have the notion of a basic equality (all must receive a base level of reward as part of being citizens), but on top of this rather than a general equality of outcome: a hierarchy of reward and recognition dependent on the individual's achievements.3

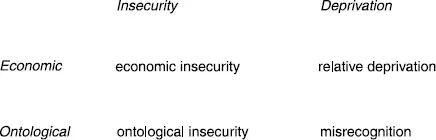

What terms are we to use when distributive justice or recognition is wanting? When material reward is unjustly allocated we commonly use the term ‘relative deprivation’, when recognition is denied someone we call this ‘ontological insecurity’. But let us explore these further. We can talk of two aspects of unfairness – deprivation and insecurity, and two dimensions – economic and ontological. This gives us four bases of disaffection (see Figure 1.1).

How does this help inform us as to the genesis of crime and punishment? First, a major cause of crime lies in deprivation. That is, very frequently, the combination of feeling relatively deprived economically (which causes discontent) and misrecognised socially and politically (which causes disaffection). The classic combination is to be marginalised economically and treated as a second-rate citizen on the street by the police. Second, a common argument is that widespread economic and ontological insecurity in the population engenders a punitive response to crime and deviancy (see for example Luttwak 1995; Young 2000).

Figure 1.1 The dimensions of disaffection

As we shall see in the process of the transition from modernity to late modernity, powerful currents shake the social structure transforming the nature of relative deprivation, causing new modes of misrecognition and exclusion, whilst at the same time being accompanied by widespread economic and ontological insecurity. The purchase of each of these currents impacts differentially throughout the social structure by each of the prime social axes of class, age, ethnicity and gender.

The journey into late modernity and mapping the terrain

How can long-term purposes be pursued in a short-term society? How can durable social relations be sustained? How can a human being develop a narrative of identity and life history in a society composed of episodes and fragments? The conditions of the new economy feed instead on experience which drifts in time, from place to place, from job to job.

(Sennett 1998: 26–7)

If one wishes to travel anywhere one must know what terrain one has to travel over, what means of travel are available and last, and by no means least, where one wants to go. In reality over the last twenty years the terrain, the structure of society, has radically changed, effective means of intervening in the social world have profoundly altered and, most important, the metropolis of possibility and desire in which we find ourselves has altered beyond recognition.

The last third of the twentieth century witnessed a remarkable transformation in the lives of citizens living in advanced industrial societies. The Golden Age of the post-war settlement, with high employment, stable family structures and consensual values underpinned by the safety net of the welfare state, has been replaced by a world of structural unemployment, economic precariousness, a systematic cutting of welfare provisions and the growing instability of family life and interpersonal relations. And where there once was a consensus of value, there is now burgeoning pluralism and individualism (see Hobsbawm 1994) . A world of material and ontological security from cradle to grave has been replaced by precariousness and uncertainty, and where social commentators of the 1950s and 1960s berated the complacency of a comfortable ‘never had it so good’ generation, today they talk of a ‘risk society’ where social change becomes the central dynamo of existence and where anything might happen. As Anthony Giddens puts it: ‘to live in the world produced by high modernity has the feeling of riding a juggernaut’ (1991: 28; see also Beck 1992; Berman 1983).

Such a change has been brought about by market forces which have systematically transformed both the sphere of production and consumption. This shift from Fordism to post-Fordism involves the unravelling of the world of work where the primary labour market of secure employment and ‘safe’ careers shrinks and the secondary labour market of short-term contracts, flexibility and insecurity increases, as does the growth of an underclass of the structurally unemployed. It results, in Will Hutton's catchphrase, in a ‘40:30:30 society’ (1995) – 40 per cent of the population are in tenured secure employment, 30 per cent in insecure employment, and 30 per cent are marginalised, idle or working for poverty wages.

Second, the world of leisure is transformed from one of mass consumption to one where choice and preference is elevated to a major ideal, and where the constant stress on immediacy, hedonism and self-actualisation has had a profound effect on late modern sensibilities (see Campbell 1987; Featherstone 1985). These changes, both in work and in leisure, characteristic of the late modern period, generate a situation of widespread relative deprivation and heightened individualism. Market forces generate a more unequal and less meritocratic society and encourage an ethos of every person for him- or herself. Together, these create a combination which is severely criminogenic. Such a process is combined with a decline in the forces of informal social control, as communities are disintegrated by social mobility and left to decay as capital finds more profitable areas to invest and develop. At the same time, families are stressed and fragmented by the decline in community systems of support, the reduction of state support and the more intense pressures of work (see Currie 1997; Wilson 1996). Thus, as the pressures which lead to crime increase, the forces which attempt to control it decrease.

The journey into late modernity involves both a change in perceptions of the fairness of distributive justice and in the security of identity. There is a shift in relative deprivation from being a comparison between groups (what Runciman [1966] calls ‘fraternal’ relative deprivation) to that which is between individuals (what Runciman terms ‘egoistic’ relative deprivation). The likely effect on crime is, I would suggest, to move from a pattern of committing crimes outside of one's neighbourhood onto other richer people to committing crimes in an internecine way within one's neighbourhood. In other words, the frustrations generated by relative deprivation become focused inside the ‘community’ rather than, as formerly, projected out of it.

Thus Roger Hood (Hood and Jones 1999) and his associates, in their fascinating oral history of three generations in London's East End, find a sharp difference between the 1980s generation, who left school in the late 1970s and 1980s, and those of the 1930s and 1950s. Again and again, the older respondents talk of their lack of fear of crime in the earlier periods, and make the distinction between the tolerated crime committed against shops, warehouses, rich outsiders and the anathema of crime against one's family, friends or neighbours. For the 1980s generation, all of this had changed:

crime had formerly been seen as an activity on the margins of everyday relationships, something that a few segregated members of the community did to outsiders: the bosses and impersonal companies. It was now perceived to be increasingly an internal threat. Indeed some young men, as well as women described it as pervasive within their neighbourhoods.

(Hood and Jones 1999: 154–5)

But it is also in the realm of identity that relative deprivation is increased and transformed. For here, on one side, you have raised expectations: the spinoff of the consumer society is the market in lifestyles. On the other side, both in work and in leisure, there has been a disembeddedness. That is, identity is no longer secure; it is fragmentary and transitional – all of which is underscored by a culture of reflexivity which no longer takes the world for granted. The identity crisis permeates our society. As the security of the lifelong job and the comfort of stability in marriage and relationships fade, as movement makes community a phantasmagoria where each unit of the structure stays in place but each individual occupant regularly moves, where the structure itself expands and transforms and where the habit of reflexivity itself makes choice part of everyday life and problematises the taken for granted – all of these things call into question the notion of a fixed, solid sense of self. Essentialism offers a panacea for this sense of disembeddedness.

The identity crisis and the attractions of essentialism

In The Exclusive Society (1999) I discuss the attractions of essentialism to the ontologically insecure and denigrated. To believe that one's culture, ‘race’, gender or community has a fixed essence which is valorised and unchanging is, of course, by its very nature the answer to a feeling that the human condition is one of shifting sands, and that the social order is feckless and arbitrary. To successfully essentialise oneself it is of great purchase to negatively essentialise others. That is to ascribe to the other either features which lack one's own values (and solidity) or which are an inversion of one's own cherished beliefs about one's self. To seek identity for oneself, in an essentialist fashion, inevitably involves denying or denigrating the identity of others.

Crime and its control is a prime site for essentialisation. Who, by definition, could be a better candidate for such a negative ‘othering’ than the criminal and the culture that he or she is seen to live in? Thus the criminal underclass, replete with single mothers living in slum estates or ghettos, drug addicts committing crime to maintain their habit and illegal immigrants who commit crime to deceitfully enter the country (and continue their lives of crime in order to maintain themselves), have become the three major foci of emerging discourses around law and order of the last third of the twentieth century. These types can be summed up as the welfare ‘scrounger’, the ‘junkie’ and the ‘illegal’.

This triptych of deviancy, each picture reflecting each other in a late modern portrait of degeneracy and despair, comes to dominate public...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Crime, Disorder and Community Safety

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: beyond criminology?

- 1 Identity, community and social exclusion

- 2 Joined-up but fragmented: contradiction, ambiguity and ambivalence at the heart of New Labour's ‘Third Way’

- 3 Evaluation and evidence-led crime reduction policy and practice

- 4 Crime, community safety and toleration

- 5 ‘Broken Windows’ and the culture wars: a response to selected critiques

- 6 Ethnic minorities and community safety

- 7 The new correctionalism: young people, Youth Justice and New Labour

- 8 Crime victimisation and inequality in risk society

- 9 Distributive justice and crime

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Crime, Disorder and Community Safety by Roger Matthews,John Pitts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Criminal Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.