- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The period 1945-1949 is generally acknowledged as a critical period for the German people and their collective history. But it did not, Manfred Malzahn argues, lead inevitably to the construction of the Berlin Wall. As in 1989, so in 1945 the German people were prepared to break away from established patterns, to reassess, if need be, what it meant to be German. Then, as now, Germans East and West wanted order and stability; food, shelter, clothing and work. Using numerous documents from the immediate post-war years, Malzahn rescues the period from the burden of selective hindsight and nostalgia that has obscured the contemporary situation. The documents, which have been fully annotated, reflect life at all levels from politics to fashion, and contain both Allied and German viewpoints. They are bound together by an emphasis on communication, on Allied/German interaction, and on the Germans' dialogue with their past and expressions of their aspirations.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 ‘Zero hour’

1.1. TOWARDS THE END OF THE WAR

As the fighting entered its final stages in 1945, the question how to achieve the transition to peace after the imminent military victory was raised more frequently, and with more urgency than before on the side of the Allies. A meeting between the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (born 1874)1 and US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945) at Casablanca in January 1943 had established unconditional surrender as the Allied precondition for peace; two years later the possible consequences of such a surrender seemed to call for a clearer definition of Allied policies regarding post-war Germany. Of prime importance was the issue of government: would any form of German authority be allowed to exist, or would the Allies assume total control? There was some doubt as to whether a hard line might not prolong the fighting by making those who might have been willing to overthrow Hitler in order to achieve peace on more lenient terms, like the conspirators who attempted to kill him on 20 July 1944, rally round the cause of defending their country to the last. In the speech quoted here, Churchill takes a clear stance against any kind of bargain with any such parts of the German leadership, but at the same time emphasises that the occupying forces will not be looking for revenge against the population, contrary to the Cassandra cries of Nazi propaganda. Though made in the House of Commons, this part of the statement is clearly directed at the German public: the classical reference, of somewhat obscure origin, implies the common background of Western cultural heritage as well as the victors’ claim to moral superiority.

The principle of unconditional surrender was proclaimed by the President of the United States at Casablanca, and I endorsed it there and then on behalf of this country. I am sure it was right at the time it was used, when many things hung in the balance against us which are all decided in our favour now. Should we then modify this declaration which was made in days of comparative weakness and lack of success now that we have reached a period of mastery and power?

I am clear that nothing should induce us to abandon the principle of unconditional surrender and enter into any form of negotiation with Germany or Japan, under whatever guise such suggestions may present themselves, until the act of unconditional surrender has been formally executed. But the President of the United States and I, in your name, have repeatedly declared that the enforcement of unconditional surrender upon the enemy in no way relieves the victorious Powers of their obligations to humanity, or of their duties as civilised and Christian nations. I read somewhere that the ancient Athenians, on one occasion, overpowered a tribe in the Peloponnesus which had wrought them great injury by base, treacherous means, and when they had the hostile army herded on a beach naked for slaughter, they forgave them and set them free, and they said: ‘This was not done because they were men; it was done because of the nature of Man.’

Similarly, in this temper we may now say to our foes, ‘We demand unconditional surrender, but you know well how strict are the moral limits within which our action is confined. We are no extirpators of nations, or butchers of peoples. We make no bargain with you. We accord you nothing as a right. Abandon your resistance unconditionally. We remain bound by our customs and our nature.’

Source: House of Commons Debates 407, col. 423 (18 January 1945), in: Beate Ruhm von Oppen (ed.), Documents on Germany under Occupation 1945–1954 (Oxford, 1955) pp. 3 f.

Note

1 Birth date only is given in the commentary/notes throughout the book for individuals who were alive at the end of the period covered by the book—1945–1949

1.2. THE OCCUPATION: A BRITISH VIEW

On 7 March, American forces had crossed the Rhine, the last major natural border between the Western Allies and the largest part of the Reich’s heartland. British and American armies encircled the important industrial area of the Ruhr, where the fighting still continued as the English journalist Leonard O.Mosley entered occupied territory. He had been a newspaper correspondent in Berlin from 1937 to 1939, meeting many Germans and making many friends among them in spite of his despair at the extent to which people allowed themselves to be led by Nazi ideology. His attitude to the Germans which he expresses in his Report from Germany is nevertheless sympathetic, but superior: the dilemma how to be understanding without being patronising clearly shows in his ‘hot off the press’ account published by Victor Gollancz which members of the Left Book Club could read very shortly after it was written in 1945. Most reports from Germany until the end of the war concerned themselves with military events, and Mosley’s wish to be elsewhere than where the real action was ensured that he met with some astonishment, as did the fact that his wife accompanied him into the midst of the newly conquered enemies. For him, they were already the neighbours, if not the Allies of the future, and all they needed was to be pointed in the right direction by those nations with the proper set of democratic values, and a better record of moral conduct to back it up.

Wherever we drove through the Rhineland those first weeks in April the feelings of the German people were unmistakeable. The War was not yet over but they knew it was lost, and they were engaged in an instinctive effort to save something from the wreck. There were the Nazi officials who crawled and lick-spittled in an attempt to curry favour and save either their necks, their liberty, or their jobs. There were the rich industrialists and landed gentry who had friends in England or America, and were rude and unpleasant, and confident that their friend Hiram This or Viscount That would get them out of trouble. There were the odd groups of young people here and there, teen-age Hitler Jugend1 and Bund Deutsche Mädeln2 mostly, who were defiant because their spirits were sore, their burning faiths and dreams, their beliefs and ideals, destroyed by the men who so corruptly had called them forth; and now they were bewildered and angry because they had nothing. But the mass of the people were casting off National Socialism like an old coat, without grief or regret, some more and some less conscious of the guilt they shared in the support they had given it, determined to forget it and to work to re-create, in co-operation with their conquerors, the things that had been destroyed. They were fertile ground indeed, then, for a policy of re-education—if only there had been one.

Queer things happened in the Rhineland in those days. There was, for instance, the day we were in Bonn. We were walking down the street to look again at Beethoven’s house,3 and feeling sick and apprehensive as we saw the piles of bomb debris. Less than a mile away there was a battle going on, just across the river, and every now and then an over-range shell would crash somewhere near by. Yet there were Germans walking, unconcerned, in the town, and, as we got nearer to the house, a man halted, looked at us, and said in French: ‘You are going to Herr Beethoven’s house? Do not worry. It is unharmed.’

He walked with us to the house itself, and stood, a little back from us, watching our faces as we looked at it.

‘You are fond of music?’ he asked, in German this time. ‘We had many good concerts in Bonn. I wonder when we shall hear more. You have seen our University?’

No, we said; nor had we time to go today.

‘A pity,’ he said. ‘It is very fine.’ He listened for a moment to the rattle of machine-guns down the river, an expression of remote speculation upon his face. Then he fumbled in his pocket, handed us a pamphlet, clicked his heels, bowed, and turned away.

It was not a proclamation from the Werewolves,4 but a tourist pamphlet in French, containing pictures and descriptive matter about the architectural treasures of Bonn.

Source: Leonard O.Mosley, Report from Germany (London, 1945) pp. 24 f.

Notes

1 Hitler-Jugend (HJ), Hitler Youth, youth organisation of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP, National Socialist German Workers’ Party); the HJ was established in 1926, compulsory membership introduced by law of 1 December 1936

2 Misspelling of Bund deutscher Mädel (BdM), Federation of German Girls, female branch of the HJ, for girls from 14 to 18 years of age

3 The house where the composer Ludwig van Beethoven was born in 1770, open to visitors as a museum

4 Werwölfe, originally German soldiers operating behind enemy lines in the so-called Unternehmen Werwolf (Undertaking Werewolf) under the leadership of the SS; later on, Werewolf activities were to include acts of sabotage and reprisal against capitulators and collaborators carried out also by noncombatants and PoWs

1.3. THE OCCUPATION: GERMAN VIEW NO. 1

By mid-April 1945, large areas of the Reich were under Allied control. American troops were approaching Berlin from the West; the German writer Ernst Jünger (born 1895); saw them pass through the village of Kirchhorst near Hanover, where he had been living since his release from the army, shortly after sending Field Marshal Rommel a copy of his essay Der Friede (Peace). He had seen regular military service as a volunteer in World War I, receiving the highest Prussian decoration for bravery ‘Pour le mérite’, and was called up again at the beginning of World War II. The soldier’s life is portrayed in jünger’s early fiction as an archetypal male experience, which he describes in a detached, realistic style. Then he turned to the worker as another archetypal figure; both endeared him to different both endeared him to different political factions on the right and left respectively. Jünger, however, remained aloof, never siding with any camp, although he published a novel that was generally understood as an attack on the Nazi system, in 1939: Auf den Marmorklippen (On the Marble Cliffs). In 1945, he was the commander of the Volkssturm at Kirchhorst, surrendering the village to the Americans; in 1944, he had been in the know about, but not part of the conspiracy to take Hitler’s life. This extract from his diary is an example of a characteristically distanced attitude to events happening close by, and after all not without personal involvement of the observer.

Kirchhorst, 13 April 1945

At the crack of dawn the Americans moved on. They left a halfdevastated village behind. We are exhausted like children after a fair with its masses of people, the shooting, the shouting, sideshows, horror cabinets and music tents.

At the school during the morning, I talked about this with a group of villagers and refugees who had gathered there after the rainstorm, half animated, half giddy, in a mood which the Berliner describes as ‘spun through’.1 The opinion was that the worst had passed us by. In other places, such as the level crossing at Ehlershausen where the Hitler Youth knocked out a tank, things are said to look different. The fortunate thing above all was that during the night before the Americans moved in, the Flak unit had cleared the field, after blowing up their guns. Negotiations between Party, Wehrmacht2 and Volkssturm3 had filled the preceding days. I was busy with the Kreisleiter4 as well as my flu, and Löhning5 kept me informed about what was going on at the Gau6 administration. When the Party finally left for Holstein, things became simpler. I was to knock out two or three tanks with my farmers, to cover the retreat.

On this occasion I once again saw clearly that war has also a theatrical side, which you cannot learn from the files, let alone from history. There are, as in private life, motives which move in undercurrents, and rarely ever emerge. People are busily firing at the landscape, to make a noise and to get rid of the ammunition, and then they can say after time-honoured fashion that they defended themselves to the last bullet. They hold positions exactly as long as they can still get away, then doctor their reports and vanish as if by magic. Of course I knew what the good people had in mind while we were negotiating about defence, but I knew better than to let it show, because there are situations in which people should make things easier for one another. Also, in the middle of such games, now and then trumps are called, i.e., the one who shows his hand too early is taken away and shot. This endows the exit with the necessary respect; as seen again here, too.

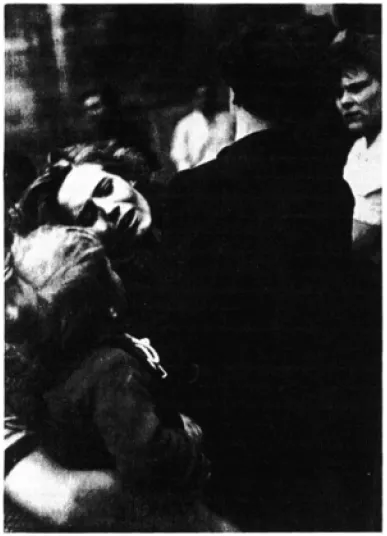

Figure 1 Facing an uncertain future: refugees during the evacuation of an air raid shelter

To make it obvious for myself, I stopped at the fire station on the way to my school, to look at the corpse lying there on the floor. The face was distorted as from a heavy fall or blow. The coat was open; below the left nipple, there was the pale gleam of a small bullet wound. The herculean man had been a dreaded person; the night before, he had still delivered a fanatical speech a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on German political parties

- The German question: history and semantics

- 1 ‘Zero hour’

- 2 Partitions

- 3 Natives and aliens

- 4 Foundations of a ‘new’ society

- 5 Economic reorganisation

- 6 Homecomers and refugees

- 7 Transport and communication

- 8 The press

- 9 ‘Low’ culture

- 10 ‘High’ culture

- 11 Parties and trade unions

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Germany 1945-1949 by Manfred Malzahn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.