Chapter 1

Before you start

Getting going

Welcome to the world of research! A student research project is an opportunity to apply all the ‘real world’ skills which degree programmes aim to impart. Overall, your project should reflect your ability to sustain an in-depth enquiry on a health-related topic. The broad field of health-related research includes topics which may explore largely psychological, social, biological, medical or nursing issues, and examples in these fields are chosen throughout this volume.

As the first stage of beginning to plan your project, you need to think about what is practical to achieve as opposed to what is ideal or desirable. Thus you have an ultimate deadline by which to complete and write up your project report. You may also be limited by the availability of practical resources such as specialised facilities. A frequent constraint arises through the need to gain access to certain client or patient groups for some investigations and, if the idea you have in mind involves access to such individuals, you need to check in advance that the necessary permission is obtainable. You may decide to conduct a study because there is particular expertise, in the form of supervision and a research tradition in your department, in a particular field, and such support can be invaluable. Your tutors may suggest a project is carried out within particular areas, although the precise way in which it is conducted may be open to discussion and negotiation.

The planning stage is perhaps the most crucial stage in the conduct of any piece of research.

Research which is entered into where the aims are woolly and ill-defined on the assumption that ‘things will work out in practice’ is almost certainly doomed to failure. The process of deciding upon a suitable research question and how to go about addressing it should not be rushed. You may have a few general ideas within some areas of inquiry and may need to hone your ideas by consulting literature in the library or conducting some CD-ROM or internet searches. You need to get an early ‘feel’ for what is known about the subject you have in mind and whether previous research has come up with definite conclusions. You will probably also want to bounce your ideas off friends, colleagues or members of academic staff before finally deciding on your particular research question. Alongside this process of deciding on your research question, you need to be thinking about the techniques and methods that you might employ in order adequately to address it.

The processes that you may employ in order to assist the planning of your research are as many and varied as there are researchers. Some people find that they like to sit down with a large sheet of paper and make a visual representation of the overall structure of the project, perhaps in the form of a flow diagram with arrows and boxes representing various stages of the data collection process. Others may find that the use of a project management package on a personal computer can be helpful to identify critical stages and intermediate goals to be achieved by certain dates so that the project can be completed on time. An example chart of the output from such software is shown in Chapter 14 of this book. Yet others find a more unstructured approach to be helpful. For instance, most word processors have an outliner which allows you to set up in a hierarchical manner headings and sub-headings under which ideas about the project can be filled in as they come to you.

Whatever method is adopted, you will find it much easier if you are organised! So develop a system for keeping track of your references from the earliest stage. A haphazard pile of reprints and hastily scribbled notes are unlikely to provide the degree of organisation you will need. Typing referencing information about relevant papers, together with a summary of what they are about, into a database on a personal computer is a much more systematic approach.

An equivalent goal can be reached by the use of a simple card index system; cards can then be sorted in order of topic or author. Your database of relevant literature will grow and evolve over the course of your study as more work is identified of relevance to your research, and you should be thinking about the implications of it all for your own project.

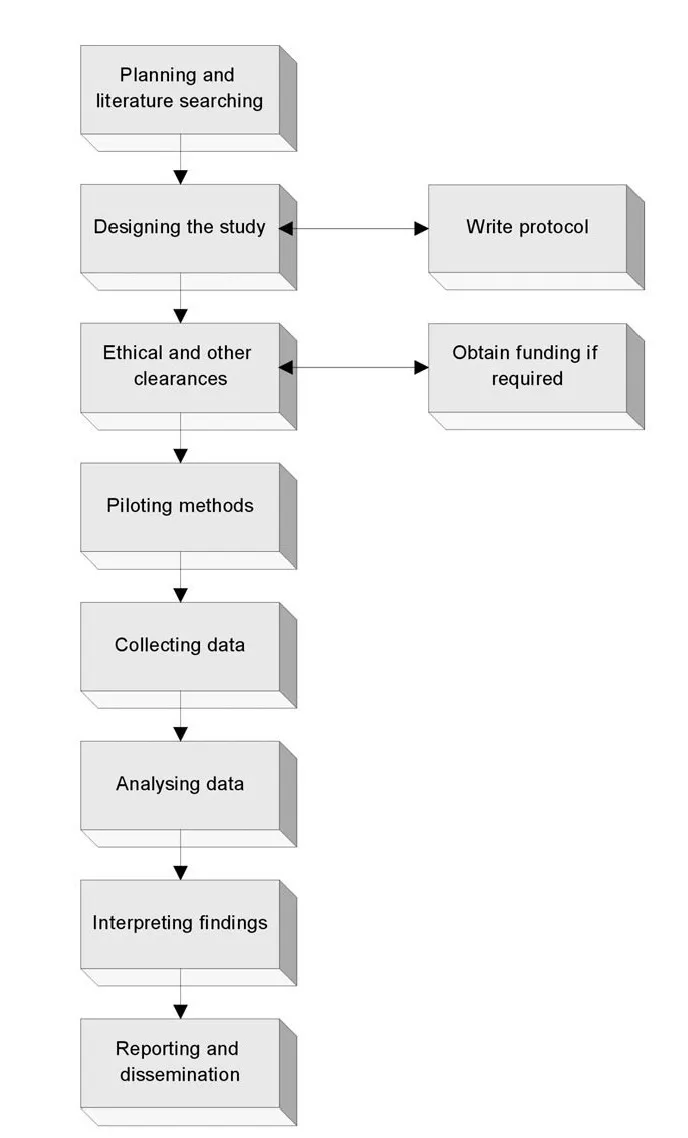

The overall general stages involved in planning, implementing and reporting a research study are illustrated in Figure 1.1. Although this is the general sequence of steps involved, it should be borne in mind that the process is not always such a linear and sequential one. For example, although the background literature searching in most studies should come at an early stage when the study is being planned, this may continue throughout the project. Data collection, analysis and interpretation sometimes proceed hand in hand, especially in qualitative research studies as is discussed in Chapters 10 and 11.

In planning the timescale of your project, you should allow a contingency element for slippage at all critical stages of your investigation. One of the key distinguishing features of successful planning of a research project is the ability to anticipate, as far as possible, potential difficulties which may arise along the way and to make contingency plans in the event of them arising. Critical pieces of laboratory equipment can fail, and may take weeks or months to be repaired. Or permission may suddenly be withdrawn by an organisation once a study has commenced in response to ongoing events. It is normal for some research subjects to fail to keep appointments or for people to forget to do things. The way that you handle the research problems will be an indicator of the quality of your research and of your initial planning to meet such contingencies.

The outcome of any non-trivial piece of research is never certain, otherwise there would be little point in carrying out the work. However, some investigations are more risky than others in the likelihood of generating usable data. In particular, it is vital that the methods of data collection and analysis that you have selected must be capable, in principle, of answering the questions originally posed, even if in the event the study was inconclusive. A study which cannot reasonably be expected to provide an answer, even in principle, to the questions you have set in your aims and objectives is going to fail.

Figure 1.1 Steps involved in a research study from initial idea to conclusion

The research process

It is a main aim of this book to encourage a well thought out project conducted to high standards of research inquiry. Although my background is rooted within the scientific research tradition, some researchers within the very broad field of health-related research would not necessarily agree with their work being labelled as ‘scientific’. Enthusiasts of ‘post-positivistic’ or ‘new paradigm’ research tend to downplay measures taken to increase objectivity, which are viewed as being at the expense of the naturalness of the setting and of an intuitive and empathetic approach to the understanding of the world of people. This issue is taken further in this book on the discussion of qualitative approaches in Chapter 10; the broad field of health research has been enriched by a great diversity and variety of research approaches and methods. Whatever our philosophical and emotional leanings in the field of health, however, it is important that researchers demonstrate an underlying integrity in their enquiries.

People often carry out a piece of research because they have perhaps a passionate, or personal, interest in the area of inquiry – whether this is gender discrimination, the effect of budget cuts on patient care or treatment for alcoholism. These sincerely held personal convictions and values are not, by themselves, reasons for not conducting research within the field, and indeed motivate much work which appears in the scientific literature. Nevertheless, it is danger to seize upon a project as an opportunity to ‘prove a point’ and attempt to present the results in such a way as to influence existing systems in desired directions. It is usually obvious to any disinterested reader when this has been done, and this approach is therefore, apart from being scientifically unethical or dishonest, also ultimately self-defeating. Policy indications may, of course, flow from findings in due course, and if these are recognised by the researcher they should be included in the discussion – but they will only be valid if an unbiased stance has been taken towards the collection and analysis of the data.

Where research integrity is compromised, research treads a dangerous path. Some of the worst excesses have been committed by researchers, once regarded as eminent, whom we now know to have systematically distorted, and even fabricated, their research data for ideological ends. The history of the development of IQ tests and their subsequent application in the early and middle years of the twentieth century to ‘prove’ the genetic inferiority of black and working class people is a sorry and salutary tale for any researcher. Research of course is never neutral or ‘value free’; it is, after all, conducted by human beings with particular values and attitudes and is carried out within the context of a social structure where individuals have particular roles and responsibilities. Society, in the form of established structures, will ultimately set the agenda for research – either directly, for example, through the funding of research or more subtly through the questions and paradigms, or systems of beliefs, that it will support.

Books on research often include some brief – and occasionally thought provoking – ‘philosophy’ written for the benefit of the aspiring researcher, which is designed to get you thinking critically about the process and context as much as the outcomes and specific methods of your research. So here goes! The notion of the ‘gradual accumulation of knowledge towards the truth’ is generally not how research proceeds. Rather, it is normally a case of blind alleys and false trails, and sometimes of going completely in the wrong direction.

The currently accepted ‘pot’ of knowledge in any one social or scientific discipline can be likened to a pot of coins; some coins in the pot will be bright and shiny, and these represent carefully designed, well conducted studies producing reliable data. These will mingle with many others which are tarnished to one degree or another through bias, ideological distortion on the part of the researcher, or simply bad design. The journal peer review refereeing system – whereby research papers are sent out by journal editors to fellow researchers in the field for comment – will generally weed out the worst excesses, so that hopefully most of the bent coins will never even get thrown in. However, research is a democratic process where all shapes and sizes of coin, and different currencies, are thrown into the pot and made available to the research community.

Sometimes the odd bad penny will be shown to be a forgery and will be ejected. Most of the time, however, the bad stays in, confusing the picture until it becomes recognised only very slowly. As research directions change, better theories emerge and previous papers fail to be cited in the literature. Unfortunately, the abilities of those who are picking up the coins – the other research workers and society generally – are impaired, and it is difficult to distinguish the shiny from the dull. Some will have the insight, as well as the necessary resources in the form of research grants, to conduct large studies or buy the electron microscopes, the laboratory equipment and so on to improve their discrimination and will be generally ahead in their thinking. Many others will have to accept, or be content to accept, what others tell them about the contents of the pot.

Very occasionally a gold coin – a real conceptual advance in a field – will be so shiny that it will stand out to most people, although not necessarily at first. A minority of sceptics will argue that it is false gold, and sometimes history will prove them right. Once in a blue moon, the whole pot is knocked over and a different vessel of a new shape and size has to be started again. So a Darwin or an Einstein will come along and Newton’s classical mechanics is supplanted by Einstein’s relativity theory, providing a major new paradigm wherein it becomes necessary to ask completely different sets of questions. These qualitative shifts in the mindset and world view of scientists have been described as ‘scientific revolutions’ by the philosopher of science, Thomas Kuhn.

A worthwhile contribution to this fund of knowledge or ideas should be the aim of a good research study, even if the particular objectives of a study are quite limited and practical. To achieve this, perhaps the over-riding factor to guard against by the conscientious investigator is bias. There are many sources of potential bias which can affect a research project at any level; some are inherent in the way studies are designed, some by the way studies are conducted. This book aims to point up such potential distorting influences and ways of guarding against them. For example, experiments are often conducted ‘blind’ – that is, without knowledge of which people have been allocated to which group in order to minimise the effects of experimenter expectations on the outcome, a form of bias which has been called the Rosenthal effect. Other techniques which are used by researchers to minimise bias, or systematic error, in their methods and approach are specifically discussed in Chapter 3 which introduces different ways of collecting data; Chapter 4 discusses issues concerned with sampling, Chapter 5 concentrates upon questionnaire design techniques, Chapter 6 discusses the experimental method and Chapters 10 and 11 are devoted to a discussion of qualitative approaches. All researchers within the field of health, whatever their method of approach, need to be aware from the start of potential ethical issues involved in their projects and the next chapter introduces some of these.

Action points

- Start your collection of references and other material as soon as possible.

- Explore the feasibility of the techniques you have in mind.

- Consider the strengths and weaknesses of alternative research designs.

- Plan out your approach.

Chapter 2

Matters ethical and otherwise

Virtually all research raises some questions of ethical interest. It is not only researchers at the ‘leading edge’, where animal or human experimentation is concerned, who need to be acutely aware of the ethical implications of what they are contemplating. An apparently innocuous questionnaire survey may have considerable ethical ramifications, for instance on the attitudes or psychological state of those taking part, depending on how and why it is being administered and used. The identification and selection of appropriate individuals in a sample is subject to ethical considerations. Likewise, the reporting of research results demands high ethical standards and integrity from the researchers.

Some projects may involve the use of patients or clients selected, for example, from hospital or GP lists or may involve conducting work using NHS premises or facilities. Appropriate local research ethics committee clearance needs to be obtained in advance for any such project work, even if the contact with the patients or ex-patients involves no more than the sending out of a letter or questionnaire. Many such committees only meet occasionally and it is important to submit an ethical committee application well in advance of the planned start date for data collection.

Although ethical committee procedures differ, depending upon the health authority, you are likely to be sent a lengthy form to complete. This will require information concerning, for example:

- qualifications and function of people involved in the project

- objectives of the study

- scientific background to the research

- design of the study

- information on potential benefits and risks of the work

- how research subjects will be recruited

- how informed consent will be achieved

- precautions taken to protect confidentiality

- copies of information sheets, consent forms and questionnaires.

Prior to ethical committee approval being obtained, it is, of course, permissible to carry out some preliminary work on the project such as the devising of questionnaires and literature searching, but you need...