This book is available to read until 4th December, 2025

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 4 Dec |Learn more

Philosophy Of Language

About this book

This engaging and accessible introduction to the philosophy of language provides an important guide to one of the liveliest and most challenging areas of study in philosophy. Interweaving the historical development of the subject with a thematic overview of the different approaches to meaning, the book provides students with the tools necessary to understand contemporary analytical philosophy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Philosophy Of Language by Alex Miller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Frege: Semantic Value and Reference1

We noted in the preface that contemporary philosophy of language is motivated in large part by a desire to say something systematic about our intuitive notion of meaning, and we distinguished two main ways in which such a systematic account can be given. The most influential figure in the history of the project of systematizing the notion of meaning (in both of these ways) is Gottlob Frege (1848–1925), a German philosopher, mathematician and logician, who spent his entire career as a professor of mathematics at the University of Jena. In addition to inventing the symbolic language of modern logic,2 Frege introduced some distinctions and ideas that are absolutely crucial for an understanding of the philosophy of language, and the main task of this chapter and the next is to introduce these distinctions and ideas and to show how they can be used in a systematic account of meaning.

1.1 Frege’s Logical Language

Frege’s work in the philosophy of language builds on what is usually regarded as his greatest achievement, the invention of the language of modern symbolic logic. This is the logical language that is now standardly taught in first-year introductory courses on the subject. As noted in the preface, a basic knowledge of this logical language will be presupposed throughout this book, but we’ll very quickly run over some of this familiar ground in this section.

The reader will recall that logic is the study of argument. A valid argument is one in which the premises, if true, guarantee the truth of the conclusion: that is, in which it is impossible for all of the premises to be true and yet for the conclusion to be false. An invalid argument is one in which the truth of the premises does not guarantee the truth of the conclusion: that is, in which there are at least some possible circumstances in which all of the premises are true and the conclusion is false.3 One of the tasks of logic is to provide us with rigorous methods of determining whether a given argument is valid or invalid. In order to apply the logical methods, we have first to translate the arguments, as they appear in natural language, into a formal logical notation. Consider the following (intuitively valid) argument:

(1)If Jones has taken the medicine then he will get better;

(2)Jones has taken the medicine; therefore,

(3)He will get better.

This can be translated into Frege’s logical notation by letting the capital letters “P” and “Q” abbreviate the whole sentences or propositions out of which the argument is composed, as follows:

P: Jones has taken the medicine

Q: Jones will get better.

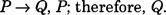

As will be familiar, the conditional “If …then …” gets symbolized by the arrow “…→…” The argument is thus translated into logical symbolism as

The conditional “→” is known as a sentential connective, since it allows us to form a complex sentence (P → Q) by connecting two simpler sentences (P, Q). Other sentential connectives are “and”, symbolized by “&” “or”, symbolized by “v”; “it is not the case that”, symbolized by “−”; “if and only if’, symbolized by “↔”. The capital letters “P”, “Q”, etc. are known as propositional variables, since they are abbreviations for sentences expressing whole propositions. For instance, in the example above, “P” is an abbreviation for the sentence expressing the proposition that Jones has taken the medicine, and so on. Given this vocabulary, we can translate many natural language arguments into logical notation. Consider:

(4)If Rangers won and Celtic lost, then Fergus is unhappy;

(5)Fergus is not unhappy; therefore

(6)Either Rangers didn’t win or Celtic didn’t lose.

We assign propositional variables to the component sentences as follows:

P: Rangers won

Q: Celtic lost

R: Fergus is unhappy.

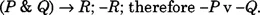

The argument then translates as

Now that we have translated the argument into logical notation, we can go on to apply one of the logical methods for checking validity (e.g. the truth-table method) to determine whether the argument is valid or not (in fact this argument is valid, as readers should check for themselves).

The logical vocabulary described above belongs to propositional logic. The reason for this tab is obvious: the basic building blocks of the arguments are sentences expressing whole propositions, abbreviated by the propositional variables “P”, “Q”, “R”, etc. However, there are many arguments in natural language that are intuitively valid but whose validity is not captured by translation into the language of propositional logic. For example:

(7)Socrates is a man;

(8)All men are mortal; therefore

(9)Socrates is mortal.

Since (7), (8) and (9) are different sentences expressing different propositions, this would translate into propositional logic as

P; Q; therefore, R.

The problem with this is that whereas the validity of the argument clearly depends on the internal structure of the constituent sentences, the formalization into propositional logic simply ignores this structure. For example, the proper name “Socrates” appears both in (7) and (9), and this is intuitively important for the validity of the argument, but is ignored by the propositional logic formalization, which simply abbreviates (7) and (9) by, respectively, “P” and “R”. In order to deal with this, Frege showed us how to extend our logical notation in such a way that the internal structure of sentences can also be exhibited. We take capital letters from the middle of the alphabet “F”, “G”, “H”, and so on as abbreviations for predicate expressions; and we take small case letters “m”, “n”, and so on as abbreviations for proper names. Thus, in the above example we can use the following translation scheme:

| m: | Socrates |

| F: | … is a man |

| G: | … is mortal. |

(7) and (9) are then formalized as Fm and Gm respectively. But what about (8)? We can work towards formalizing this in a number of stages. First of all, we can rephrase it as

For any object: if it is a man, then it is mortal.

Using the translation scheme above we can rewrite this as

For any object: if it is F, then it is G.

Now, instead of speaking directly of objects, we can represent them by using variables “x”, “y”, and so on (in the same way that we use variables to stand for numbers in algebra). We can then rephrase (8) further as

For any x: if x is F, then x is G

and then as

For any x: Fx → Gx.

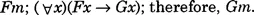

The expression “For any x” (or “For all x”) is called the universal quantifier, and it is represented symbolically as (∀x). The entire argument can now be formalized as

The type of logic which thus allows us to display the internal structure of sentences is called predicate logic, for obvious reasons (in the simplest case, it represents subject-predicate sentences as subject-predicate sentences). Note that predicate logic is not separate from propositional logic, but is rather an extension of it: predicate logic consists of the vocabulary of propositional logic plus the additional vocabulary of proper names, predicates and quantifiers. Note also that in addition to the universal quantifier there is another type of quantifier. Consider the argument:

(10)There is something which is both red and square; therefore

(11)There is something which is red.

Again, the validity of this intuitively depends on the internal structure of the constituent sentences. We can use the following translation scheme:

F: … is red

G: … is square.

G: … is square.

We’ll deal with (10) first. Following the method we used when dealing with (8) we can first rephrase (10) as

There is some x such that: it is F and G.

Or,

There is some x such that: Fx & Gx.

The expression “There is some x such that” is known as the existential quantifier and is symbolized as (∃x). (10) can thus be formalized as (∃x)(Fx & Gx), and, similarly, (11) is formalized as (∃x)Fx. The whole argument is therefore translated into logical symbolism as

(∃x)(Fx & Gx); therefore (∃x)Fx.

That, then, is a brief recap on the language of modern symbolic logic, which in its essentials was invented by Frege. The introduction of this new notation, especially of the universal and existential quantifiers, constituted a huge advance on the syllogistic logic that had dominated philosophy since the time of Aristotle. It allowed logicians to formalize and prove intuitively valid arguments whose form and validity could not be captured in the traditional Aristotelian logic. An example of such an argument is

(12)All horses are animals; therefore,

(13)All horses’ heads are animals’ heads.

It is left as an exercise for the reader to formalize this argument in Frege’s logical language.4

1.2 Syntax

A syntax or grammar for a language consists, roughly, of two things: a specification of the vocabulary of the language, and a set of rules that determine which sequences of expressions constructed from that vocabulary are grammatical and which are ungrammatical (or alternatively, which sequences are syntactically well-formed and which are syntactically ill-formed). For example, in the case of the language of propositional logic, we can specify the vocabulary as follows:

Sentential connectives: expressions having the same shape as or “–” or “&” or “v” or “↔”.

Propositional variables: expressions having the same shape as “→” “P”, “Q”, “R”, and so on.

It is important to note that when working at the level of syntax that the only properties of expressions mentioned in the spec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on usage

- 1. Frege: semantic value and, reference

- 2. Frege and Russell: sense and definite descriptions

- 3. Sense and verificationism: logical positivism

- 4. Scepticism about sense (I): Quine on analyticity and translation

- 5. Scepticism about sense (II): Kripke’s Wittgenstein’s sceptical paradox

- 6. Saving sense: responses to the sceptical paradox

- 7. Sense, intention and speech-acts: Grice’s programme

- 8. Sense and truth: Tarski and Davidson

- 9. Sense, objectivity and metaphysics

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index