1 The changing primary mathematics classroom The challenge of the National Numeracy strategy

Mike Askew

Introduction

Up until the introduction of the National Curriculum (NC), primary school teachers were largely free to choose both the content of and approaches to teaching mathematics.While the widespread use of commercial mathematics schemes meant that variation between schools may not have been as great as this freedom might suggest, with the introduction of the National Curriculum a greater degree of equality of opportunity for pupils was expected. Central to the design of the National Curriculum was the setting of attainment targets.

Helping children achieve these levels of attainment was to be accomplished through ensuring everyone had access to the mathematics curriculum through the programmes of study. Teachers were expected to use the programmes of study flexiblyso that pupils’ different needs could be met through appropriate differentiated provision; teachers were:

free to determine the detail of what should be taught in order to ensure that pupilsachieve appropriate levels of attainment. How teaching is organised and the teaching approaches used will be also for schools to determine.

(Department of Education and Science & Welsh Office, 1987, p. 11)

So entitlement was defined in terms of an intended curriculum with the specifics of what and how still in the hands of the teachers. While the needs of the state were beginning to be catered for, in the policy documents at least the flavour was still of education primarily serving the needs of the individual. The NC ‘Policy to Practice’ document sent out to all schools emphasised the need for pupil access to ‘a broad and balanced curriculum, relevant to his or her needs’ (Department of Education and Science, 1989).

As Willan (1998) remarks ‘The National Curriculum had a deeply egalitarian rhetoric: a curriculum regardless of location, status or background’ (p. 274). But this was an egalitarian curriculum in the sense of opportunity of access and as the above quotes illustrate, two key principles were embodied in the spirit of the NC:

- that the needs of individual pupils had to be provided for;

- that the actual teaching approaches that would meet these needs should be determined by teachers.

However, with the introduction of the National Numeracy Strategy (NNS) there has been a marked shift in these principles with moves:

- away from the needs of the individual towards collective targets;

- towards increasing specification of teaching approaches.

While the only aspect of the NNS that is statutory is the requirement of primary schools to teach a daily mathematics lesson, it is clear that schools are attempting to deal with such changes. In this chapter I examine these changes in emphasis and consider some of the possible implications for teaching primary mathematics arising from them. Before looking at these in detail, I want to set the scene in terms of theories of learning and what we know about effective teaching.

Learning: acquisition or participation?

Sfard (1998) points out that theories of learning can be divided broadly along the lines of whether they rest upon the metaphor of ‘learning as acquisition’ or ‘learning as participation’. ‘Learning as acquisition’ theories can be regarded broadly as mentalist in their orientation, with the emphasis on the individual building up cognitivestructures (Alexander, 1991; Baroody and Ginsburg, 1990°; Carpenter et al., 1982; Kieran, 1990°; Peterson et al., 1984). In contrast, ‘learning as participation’ theories attend to the sociocultural contexts within which learners can take part (Brown et al., 1989; Lave and Wenger, 1991; Rogoff, 1990°).

While some writers argue for the need for a paradigm shift away from (or even rejecting) acquisition perspectives in favour of participation, I agree with Sfard in the suggestion that the metaphors are not alternatives but that both are necessary and each provides different insights into the nature of teaching and learning. However, I would argue that whether one’s initial attention is on acquisition or participation can greatly alter the teaching approaches adopted.

One pertinent implication of viewing learning as ‘acquisition’ is the way that such a view separates the learner from what is to be learnt. If learning is coming to acquire knowledge, then there are overtones of consumers and commodities. Mathematical knowledge is a set of skills, facts and concepts that somehow have to be ‘transferred’ over to the learner, the teacher becoming some sort of shopkeeper who has access to the ‘goods’ and can, metaphorically, hand them over to the pupils. A further implicationof this metaphor for learning is the separation of responsibilities in the classroom:teachers teach and pupils learn. If the pupils fail to learn then it is either because the teacher has ‘failed to deliver the goods’ or that pupils have not managed to ‘hold onto’ them. To change the metaphor, knowledge as a liquid commodity can come in jugs and either teachers fail to pour it out carefully enough or pupils are ‘leaky vessels’ (Shuard, 1986) so the knowledge soon dribbles out.

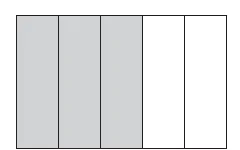

In contrast to this view, regarding knowledge as arising from participation emphasises the social nature of coming to understand. Rather than knowledge being something that exists independently of learners just waiting to be ‘passed on’, knowledgeis seen as being the result of social agreement and taking part in social practices that induct the learner into such agreements. An example should help illustrate what I mean. Have a look at the diagram below and jot down what fraction you think it represents.

Most people will respond that the diagram represents ⅗ or perhaps ⅖. But ‘read’ in a particular way then it can also be seen as representing ⅔ , 1½, 1⅔ or 2 ½ (for example, if you ‘read’ the shaded part as the unit then the whole is 1⅔ ). There is nothing inherent in the diagram itself that makes the ‘right’ answer. And, I suggest, people do not come to read this as through individual activity that they have carried out by folding paper, shading in and so on. Such activities simply provide a context within which they come to learn that the ‘accepted’ (i.e. socially agreed) way of interpreting the diagram is . They come to read it as because that is how others – teachers, textbook writers, peers – all read it. The learner has become part of the ‘community of practice’ (Rogoff, 1995) that reads fractions in this way. The idea of classrooms as ‘communities of practice’ embodies the perspective on learning as participation. Working together as a community suggests that the clear demarcation between teaching and learning suggested by the ‘acquisition’ metaphor becomes blurred. In a community of practice the teacher is a learner as well and the pupils can also teach each other. Furthermore, the responsibility for success or failure becomes a joint one. I have a copy of child’s answer to a test question on coordinates.The context is one of a ship moving over a coordinate grid and the question requires the pupil to write down ‘what to tell the ship’ in order to get it to move between two points. This particular child wrote down ‘ready, steady, go!’ The questionthis raises for me is who actually got it wrong? As teachers and test writers we are all well inducted into the (bizarre) world of mathematical questions where ships can be sentient. But the child has drawn upon a different community of practice, one possibly more familiar, one that involves giving instructions to others to get them to move. The answer tells us nothing about whether or not the child could give mathematicalinstructions, had the distinction between the different communities been made clear. (See Cooper, 2001, Chapter 13 in the companion volume Teaching Mathematics in Secondary Schools: A reader for more ideas on this.) The element of joint responsibility for success or failure came through clearly in the ‘raising attainment in numeracy project’ (Askew et al., 1997a) where close observationof teacher and pupil interactions revealed how each interpreted the other’s actions and words in ways that led to misunderstandings. For example, many of the low-attaining Year 3 pupils in the study over-relied on counting strategies. When asked to count out a collection of objects and then soon after asked how many there were they would recount the collection. When we talked this through with the teachers, they explained that clearly the children had not yet reached the stage of being able to ‘conserve’ quantities and that allowing them to recount would provide the experience they needed in order to come to be able to conserve. However, once we suggested to the teachers that they might stop the children when they started to count and ask them if they really needed to, it became clear that the children knew perfectly well how many there were. However, from the children’s perspective they appeared to be used to a practice that meant that whenever a teacher said, ‘How many are there?’ it indicated they had to count.

I do not want to suggest that it is a question of participation being ‘right’ and acquisition being ‘wrong’. Clearly children do acquire mathematical knowledge. But I do want to suggest that how they acquire mathematical knowledge, and what they have participated in, will affect the nature of that knowledge. For example, the child who only learns multiplication facts through the rote memorisation of tables will have a different understanding of the nature of multiplication from the child who learns multiplication facts through participating in a range of activities that links multiplication to problem-solving and highlights the relationship with division. So while a child might be able to answer 3 × 8 quickly they could not make the link to answering 24 ÷ 8.

Orientations towards teaching

In the King’s College study of ‘Effective Teachers of Numeracy’ (Askew et al., 1997b) the 90° teachers in the study could not be distinguished as effective (as measuredby pupils’ gains on a test of numeracy) on measures such as amount of whole-class teaching, pupil grouping or qualifications. However, through analysis of case studies of 18 of the teachers, three clusters of beliefs or ‘orientations’ characterising beliefs and understandings of the relationship between teaching and learning emerged. We dubbed these three orientations connectionist, discovery and transmission. Of the three, having a connectionist orientation was positively associated with pupil learning gains, while the learning gains of pupils with teachers demonstrating discovery or transmission orientations were lower.

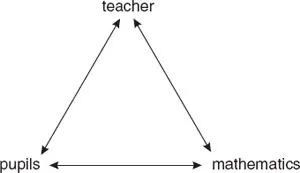

Before briefly examining some of the characteristics of a connectionist orientation from a perspective of participation I propose the following simple model: that within a mathematics lesson there is a triadic relationship between teacher, pupils and mathematics.

From our analysis what seemed to distinguish some highly effective teachers from the others was a consistent and coherent set of beliefs about how best to teach mathematics whilst taking into account children’s learning. These teachers also had a clear understanding of mathematics as an interrelated set of ideas. In particular, the theme of ‘connections’ was one that particularly stood out in our observations of and interviews with these teachers. We came to refer to such teachers as having a connectionist orientation to teaching and learning numeracy. What distinguished these teachers was the way they attended to all three bonds on the triadic model. Other orientationsthat we identified tended to focus more on one or other of the triadic bonds. So teachers who displayed a discovery orientation paid particular attention to the ...